John Strohmeyer

- 1984

Fellowship Title:

- A Steel Company's Battle to Survive

Fellowship Year:

- 1984

Saving Steel

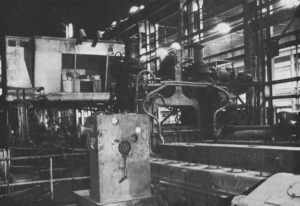

Chilly drafts of wind pour through cracked windows and holes in the roof of Bethlehem Steel’s tool shop. The interior looks like life had suddenly stopped, as though men had simply abandoned work stations and left their equipment to rot. Pigeon dirt covers rolling tables where streams of steel billets used to flow. In nearby sheds, hundreds of dies, once meticulously cut by skilled craftsmen, sit rusting and neglected because someone else’s dies are now shaping this nation’s tool steel. Part of Bethlehem Steel’s plant which hasn’t operated since late 1981. It is no longer possible to suspend disbelief of steel’s distress once you tour an integrated steel mill, as I did at Bethlehem Steel’s home plant. At least half of the five-mile facility resembled a wasteland. Under decaying roofs, piles of brick rubble were all that was left of bung furnaces where since the early 1900s thousands of workers once heated, chipped and rolled strips of steel into shapes. Giant crane-borne buckets lay rusting among strewn, disconnected motors at the steel foundry where as

City Without a Pulse

LACKAWANNA, N.Y.-It was early November, 1984, but I could already feel the chill of winter in the breeze off Lake Erie as I walked into the 8 a.m. mass at the Queen of All Saints church. The church, which fronts on Ridge Road and extends to a slag heap in the rear, serves the First Ward neighborhood that grew up next to the once-bustling Bethlehem Steel mill. Only two elderly people were in church that Thursday morning. With a demeanor of urban ministry that bides frustration, the Rev. Ronald Lord, a pleasant, middle-aged priest, bowed and blessed the congregation as though he had a full house. Two blocks away, on a littered lot down from the corner liquor store on Steelawanna Avenue, another morning ritual was drawing a little better. About a half dozen men, most of them ex-steelworkers, were huddled there, one passing a bottle wrapped in a brown paper bag, waiting, as they said they do each morning, for someone to drive up and offer them a day’s work. Lackawanna is a city

Rebuilding Bethlehem Steel

Steve Sinko, a top labor troubleshooter at Bethlehem Steel, was summoned for an emergency assignment on March 26, 1982. About 400 people were demonstrating in front of Martin Tower, headquarters of Bethlehem Steel in Bethlehem, Pa., as the United Steelworkers union protested “excessive salaries” paid to Bethlehem Steel executives. Sinko was sent to meet them at the door. The union was complaining that while steelworkers were being asked to give concessions in a period of hard times, the corporate officers were getting big bonuses. Proxy statements filed a few days earlier indicated that Donald H. Trautlein received $555,986 in 1981, nearly double the $280,880 he was paid in 1980, when he was executive vice president for five months before being named president. United Steelworkers president Lynn Williams and Bethlehem Steel president Donald Trautlein. Sinko never had to face the protesters because the demonstration ended as peacefully as it began. However, he felt flattered that the company had turned to him in a situation that had potential for big trouble. Yet, within the next year, Sinko

The Demise of Big Steel

A good way to start understanding the distress of the steel industry is to visit the Moravian Church’s ancient Nisky Hill Cemetery in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Here, on a bluff overlooking the enormous Bethlehem Steel plant beside the Lehigh River, are buried many of the leaders of the corporation. You can often guess the rank of the interred by the size of the gravestone. Towering over the rest is the huge, granite rotunda that marks the grave of Eugene G. Grace, the dynamic steelman who built Bethlehem into the nation’s No. 2 producer. A semi-circular granite bench, capable of seating 20 people, has been provided for any who might come to pay homage to either the departed chairman or to the mighty industrial complex that he developed across the river. Eugene H. Grace Next to Grace lie the remains of William H. Johnstone, a man of vision who became the head of Bethlehem’s powerful finance committee and who was one of the few in the top echelon who challenged the fundamental thesis of the old master.