A good way to start understanding the distress of the steel industry is to visit the Moravian Church’s ancient Nisky Hill Cemetery in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Here, on a bluff overlooking the enormous Bethlehem Steel plant beside the Lehigh River, are buried many of the leaders of the corporation. You can often guess the rank of the interred by the size of the gravestone.

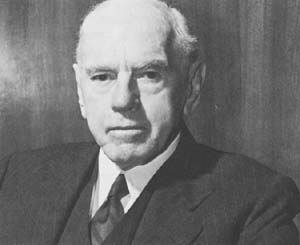

Towering over the rest is the huge, granite rotunda that marks the grave of Eugene G. Grace, the dynamic steelman who built Bethlehem into the nation’s No. 2 producer. A semi-circular granite bench, capable of seating 20 people, has been provided for any who might come to pay homage to either the departed chairman or to the mighty industrial complex that he developed across the river.

Next to Grace lie the remains of William H. Johnstone, a man of vision who became the head of Bethlehem’s powerful finance committee and who was one of the few in the top echelon who challenged the fundamental thesis of the old master. Johnstone, who had moved to New York City in retirement, returned to Bethlehem to die, virtually unnoticed. He lies, at his own request, under a simple small granite slab.

The markers are valid symbols of the differing philosophies that competed at Bethlehem–one which bred the current crisis and one which might have prevented it.

Grace’s philosophy on how to run a steel mill has been engraved in granite at Bethlehem Steel and revered even many years after he died in senility at age 83 in 1960.

“I have no doubt that the story will be one of increasing per capita use of steel in spite of the development of competing materials,” Grace declared in one of his last statements. “I have no qualms about excess capacity. The United States will never catch up to its material needs and aspirations.”

The corporation’s officers largely concurred. Steel, they assured themselves, could expect to thrive as long as it could expand capacity.

While never demeaning Grace’s remarkable achievements during 50 years in Bethlehem, Johnstone saw it differently. When the finance reins fell into his grip after Grace’s death, he spoke of new forces in the economy, new technology challenging old concepts and new nations emerging in the world steel market.

But while the world did change, pretty much as Johnstone predicted, Bethlehem Steel did not. The technological breakthroughs were made elsewhere. Other nations learned to make steel better and more efficiently and they sold it cheaper.

Bethlehem concentrated on expanding capacity. Now it is mired in red ink. It was unable to show a profit in 1982 or 1983 and started the first quarter of 1984 the same way, posting losses of $1.7 billion in the nine-quarter period.

The current theory is that imported steel, unfairly subsidized by hungry and ambitious nations, is the cause of steel’s distress. That is only partially true. The American steel industry helped create its own crisis, and Bethlehem Steel is a case study of how the industry refused to face the realities–when it had the money to adjust to them.

Last summer the International Trade Commission recommended that the Reagan administration put into effect a program of import quotas and new tariffs to protect the steel industry. As a condition for protecting about 70 percent of the domestic steel product, the commission asked that the industry make a commitment to modernize and otherwise increase competitiveness. The steel companies and unions largely cheered the decision. But in September, the president rejected the ITC’s advice and opted instead to pursue negotiated limits on foreign steel.

When I became editor of the Bethlehem Globe-Times 28 years ago, the steel industry was at high tide. The signs of prosperity were often embarrassingly conspicuous. In 1959, for example, the Globe Times republished Business Week’s listings of the highest-paid executives for 1958.

Bethlehem Steel had seven names in the top 10, including the highest-paid corporate officer in the United States–Bethlehem Steel chairman Arthur B. Homer. His total compensation was $511,249. (The year before Homer had been paid $623,336, which Bethlehem’s report to stockholders claimed amounted to only $108,462 after federal income taxes).

Don Swan, a member of the legal staff who later left to become a vice-president at Jones & Laughlin steel company, recalled the mood: “Bethlehem at that time had the reputation that its hallways were lined with gold and when you became employed they gave you a pick to mine the gold.”

The extravagance at the top was not lost on the hard-hat steel-worker, whose job is hot, dirty, monotonous, ear-shattering, strenuous and often dangerous.

Joseph Mangan, former Bethlehem city councilman who rose from the ranks to become president of a union local at the steel company, remembers that his first job in the early 1940s was to stand by as a stretcher bearer at the Coke Works where batteries of ovens convert coal to coke.

Mangan recalled what it was like to work there:

“The heat goes up to 190 degrees when they ‘push’ an oven. A guy wearing wooden shoes walks on the roof to open the oven door. A second guy pushes the coke, another guy catches it. They push 40 ovens, 50 ovens…they’d push until they keeled over.”

Working conditions are different today. Some mills even have air-conditioned pusher cabs to protect workers from the heat, and computerized operations have reduced many of the dangers. But embittered by the past and incited by the big bonuses paid at the top, the steelworkers set out early to get their own.

The United Steelworkers Union was founded in violence in 1942 and hostility remained its trademark. There were steel strikes in 1946, 1948, 1952, 1955 and 1956. Some lasted a few days. Some a few months. At least three involved full-scaled confrontations with governments. Harry Truman even seized the mills in 1952, forcing strikers back to work.

But each time the outcome was the same. The steel companies handed out wage increases that outran any other pay boosts in U.S. industry. Then they raised prices to whatever levels were necessary to satisfy profits, stockholder returns and the new pay scales, which also were adjusted for white-collar workers.

The companies were able to do this from the post-war years to well into the 1950s because the steel industry was actually an oligarchy. Competition was virtually nonexistent. When one company raised prices, the others followed. Up to this point, Japanese steel was inferior and Europe was still rebuilding. Steel was in such wide demand, with a flourishing peacetime economy, that American mills could sell all they produced at almost any price.

The pattern of striking, raising wages and raising prices continued into the 1950s with labor and management doing very nicely. Since bargaining was done on an industry-wide basis, all companies were bound by the same labor contracts. Labor’s hefty demands, management found, were easier to accept than resist. And the steelworkers’ union, well aware of the situation, took full advantage of it to build its own empire.

Then came the strike of 1959. Steel production had fallen off the year before in a brief recession to 85 million tons, the lowest since 1947. Profits were down, costs were getting out of line and the industry decided it was time to challenge the union not only on wages but also on padded work crews and inflexible work rules.

With a now-or-never attitude, a new negotiating team headed by U.S. Steel’s blunt R. Conrad Cooper, a former Minnesota football star, was sent into battle.

The steelworkers were ready. They refused to give an inch on work crew reduction, proclaiming the company plan would mean the loss of jobs. No issue since the USW was founded fanned a greater fervor.

The strike started in the middle of July, and no one became too worried as steelworkers enjoyed an enforced vacation. By fall, however, the economy began to feel the effects.

While President Eisenhower continued to affirm his faith in the processes of the free enterprise system, many steel customers were less confident and turned to markets abroad.

That was the year steel buyers discovered that other nations also sold steel. At first they dealt with the Europeans and then the Japanese came on fast.

President Eisenhower invoked the Taft-Hartley Act when the strike reached its 116th day, and a contract was worked out. Management won none of the work rule changes, leaving the substantial work rule issues unresolved.

Meanwhile, imports jumped from 2 million tons in 1958 to 5 million tons in 1959. They were never again to return to the 1958 level.

Tom Crowley, a Yale graduate who became general manager of Bethlehem’s Johnstown, Pa., plant, recounts the subtle market changes after the strike.

“The big customers came back,” he said, “but we began to lose the by-products–nails, field fence and barbed wire. It was nickel and dime impact at first but it started to affect the cost structure because we were now selling a smaller piece of the product.”

“And soon we were competing with a market we could not match. Belgian barbed wire was being delivered on the docks at Baltimore at less money than it cost us to make it.”

“They should have learned several lessons after the 1959 strike,” says Don Swan, who is now a securities broker in New York. “First, if there is cheap steel out there–even if it is only 5 percent of the market–it is going to impact on the price of the other 95 percent. Second, the strike showed there was a group of steel users looking to up their profit margins and this type of user discovered the cost benefits of foreign steel.”

Meanwhile the emergence of mini-mills caused another erosion of the market. Operating with nonunion labor and adapting new technology, the mini-mills zeroed in on producing selective, high-yield commodities and produced these with a fraction of the overhead of the giant integrated mills.

Among the first lucrative markets to go were the small reinforcing bars, which were used in great amounts for the nationwide interstate highway building program.

Since reinforcing bars have no metallurgical requirement except tensile strength, they could be produced even in the little unsophisticated mills. Soon the smaller producers were beating out the big steel mills not only in supplying products for the interstate highway system but in supplying other products, ranging from bicycle axles to reinforcing bars in nuclear concrete containment vessels.

“No one paid attention to the inroads of the mini-mills,” says Mike Herasimchuk, a senior metallurgical engineer for Bethlehem Steel. “One of my assignments was to keep abreast of them. I would periodically report what the status was, what the product was and what the tonnage was.

“The response was, ‘If a guy comes on stream with 60,000 tons a year, let’s not worry about that.’ But one guy here, one guy here and one guy here and pretty soon you see the old customers disappear.”

Why worry, indeed. Bethlehem Steel produced a record 19,436,000 tons of raw steel in 1964. Confidence in the Grace dictum was unabated. As long as the company could expand capacity, profits would follow. There was no reason to worry about the imports or mini-mills now nibbling on the market.

The Grace legacy left no room for adversarial dialogue. Each director of the internal board he created was an officer employed within the company. He left not only an aging board resistant to change but he established the precedent for board behavior: lunch together in the corporate dining room at noon, golf together in the afternoon and socializing together in the evening. His word was law and it prevailed in all decisions from building new open hearths to installing a new sand trap on the 10th hole at Saucon Valley Country Club, the company’s subsidized championship course.

Many bright middle-management executives found the parochialism suffocating. They were obliged to eat in their assigned company dining room, under Bethlehem’s caste system. Their only access to the real decision-makers was to get a moment of their attention at the inbred weekend dinner party or, by some good fortune, to sit next to one on a company plane.

Undoubtedly there were advantages to a tight board, but Bethlehem’s top executives were so removed from the real world that they rarely encountered a fresh or opposite point of view. They rode no commuter express where a fertile-minded outsider might ask, “What’s the matter with you guys at Bethlehem? Haven’t you caught on to what’s happening in the rest of the world?”

The insulation was damaging for the community, too. Until chairman Edmund Martin changed the rules in the early 1970s, community involvement of Bethlehem Steel’s leading people was routinely shunned. Prior to Martin’s chairmanship, the only time I saw a major steel executive in the city was when Joseph Larkin, a vice president, called on me and my publisher to protest an editorial critical of the latest steel price increase. (After hearing out Larkin, who was paid $467,082 in 1958, I, too, had to wonder about Bethlehem Steel’s link to reality).

Yet it would be an injustice to suggest that all executives at Bethlehem were frozen into the past when Grace died.

William Johnstone sensed the coming technological revolution, and A. B. Homer, who succeeded Grace as chairman, made a bold decision that led Bethlehem Steel to make a strong bid to become a technological leader in the industry during years when profits were still healthy.

In 1961, after Johnstone amassed piecemeal plots of idle land, Bethlehem’s Homer ordered a multimillion dollar research center atop South Mountain overlooking the city. Then it brought in about 800 engineers and support personnel to staff it, an impressive commitment to the future.

However, not much happened. The new labs did help improve the product mix, notably with the development of Galvalume, an aluminum-coated sheet metal, but they did not produce the spectacular results which such a massive diversion of money and talent should have provided.

Bethlehem approached the threshold of basic discoveries on several occasions but major thrusts at new technology seemed doomed to be aborted by the in-house dissidents who argued, “Why bother with this untested stuff; we are doing very well without it.”

Continuous casting, which eliminates several costly steps in steelmaking and now has become a process within every modern mill, was then in its infancy. Bethlehem tried and abandoned it in the 1960s in two separate experiments.

A high-speed continuous slab caster, aimed at developing automotive sheet steel, was built in a pilot plant on restricted grounds in Bethlehem in concert with Republic, Youngstown and Inland Steel companies.

The experiment worked and news of its success was spread at technical meetings. However, the pilot plant was abandoned by Bethlehem because it was not a high-production unit. Yet as soon as the Japanese learned it was possible to make sheet slabs at a higher rate, they picked up the concept and became the early beneficiaries of the Bethlehem experiment.

When an in-house study in late 1960 reported that progress in continuous casting was developing rapidly and with increasing economic benefits, Bethlehem decided to go ahead with a full-scale continuous caster early in 1970.

The research committee had recommended that it be built in a Bethlehem-owned plant at either Steelton, Pa., or Seattle, but the powers in steel operations instead dictated that it be placed in Johnstown, Pa.

A four-strand billet caster, designed to produce bar, rod and wire products, was 90 percent complete when it became apparent that the limited Johnstown plant was physically ill-suited, as the committee had warned. The entire project, on the brink of operation, was abandoned and an investment of approximately $10 million was wasted.

At least one member of the study team, Mike Herasimchuk, the senior metallurgist, had argued that the caster should be completed, problems and all, if only to gain experience with the technique that was soon to revolutionize steelmaking.

But his logic failed to convince the decision-makers. The crucial technological developments in steelmaking would have to occur elsewhere, in Europe and Japan.

“We were making evolutionary changes when a technological revolution was going on,” Dalton Brion, manager of primary processes research at Bethlehem Steel, laments today.

Indeed, Bethlehem appeared almost capricious when in 1962 it made a decision to build an entirely new, conventional steel plant at Burns Harbor, Ind. Located on the shores of Lake Michigan, the new plant would give Bethlehem an access to the Detroit area automotive market.

It was one gamble that paid off. The increased capacity enabled Bethlehem to take advantage of the last remaining large consumption years of the 1970s. Bethlehem’s profit soared to $342,034,000 in 1974.

However, the forces set in motion with the 1959 strike were soon to overwhelm the company from several directions. While the damaging strike had cooled the union’s zeal to walk off the job, it had not lessened the USW drive to make its steelworkers the highest paid in the world.

With each new contract, the gap in wage costs between the American steel industry and steelmakers abroad grew wider. In 1973 the big steelmakers virtually assured the industry’s inflexibility in competing by entering into a long-term, no-strike agreement with the union.

The pact was hailed in many places as a breakthrough in labor relations but it only accelerated the distress. The automatic cost-of-living adjustments were devastating as inflation surged during the 1970s. And there were no offsetting productivity increases.

By the time the long-term agreement had run its course in 1982, the average steelworker was earning $26.29 an hour, counting fringes. Further, they were protected by total health care, had the security of supplemental unemployment benefits and one-half of the senior work force enjoyed a bonus of 13week vacations every five years.

Compounding the mounting burden was the company’s policy of adjusting their white-collar workers’ pay whenever the union received raises.

“You got more raises because of the union than you did on merit,” one researcher complained. “I don’t know that anyone ever turned them down, but pretty soon you had your hourly people making more than a foreman. It was demoralizing…a hard situation to live with.”

Meanwhile, the unthinkable happened. For years the American steel industry had told itself that its giant mills could not be surpassed in productivity or in the quality of its output.

But in 1975 Japan passed the United States in productivity. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the Japanese worker needed only 9.2 hours to produce a ton of steel–a spectacular improvement from their 25.2 man-hours in 1964. U.S. steelworkers required 10.9 man-hours, only a modest improvement over the 13.1 hours required in 1964.

Meanwhile, the mini-mills demolished the quality argument. Perfecting the continuous casting process which Bethlehem had renounced in Johnstown, mini-mills were turning out high quality steel and at far lower prices.

These small, non-unionized mills, many now producing more than 500,000 tons a year, claim a solid 20 percent of the steel market. With foreign steel draining off from 20 to 25 percent more, the big steel plants are left to scramble for the remaining 55 to 60 percent of a market that was once exclusively theirs.

American steelmakers complain that governmental environmental policies accelerated the downfall. Bethlehem Steel estimates that it alone spent $543 million during the last 10 years for environmental control equipment, much of it to comply with excessive and even conflicting rules laid down by state and federal edicts.

“Think how we could have helped ourselves if we had been spared half of that so we could invest in continuous casting or anything else to improve productivity,” one official said.

The Last Hurrah

The first harbinger of crisis occurred at Bethlehem Steel in 1977. The company failed to post a profit for the first time in more than 50 years. Several disasters, including the Johnstown flood, were major reasons for the $448,20,000 loss, but the red ink jarred the company and its communities.

Aided by a brief comeback in the economy, Chairman Lewis Foy did manage to restore profitability in the next two years. And as his last hurrah before retiring as chairman in 1980, he made a flamboyant gesture that momentarily restored a flash of opulence to the troubled company.

About 250 managers and their wives–nearly 500 in all–were transported at company expense to Boca Raton, Fla., in appreciation for pulling the company out of the mini-recession and to introduce them to Foy’s successor, Donald Trautlein.

For two days the celebrants played golf, fished the Florida waters and patronized a free, never-closing bar, winding up with a banquet at the Boca Raton country club on Thursday night before the Easter weekend.

Foy and Trautlein were the main speakers. Few in attendance can recall Foy’s amenities. However, none will forget the somber Trautlein address. He gave the subdued audience a grim and emphatic message that things would be drastically different.

“Boy, are you in for a change,” one wife remarked on leaving the banquet hall. “You’re right,” her shaken husband replied. “That was the Last Supper.”

©1984 John Strohmeyer

John Strohmeyer, editor and vice-president of the Bethlehem (Pa.) Globe-Times for 28 years, is chronicling a steel company’s battle to survive.