LACKAWANNA, N.Y.-It was early November, 1984, but I could already feel the chill of winter in the breeze off Lake Erie as I walked into the 8 a.m. mass at the Queen of All Saints church. The church, which fronts on Ridge Road and extends to a slag heap in the rear, serves the First Ward neighborhood that grew up next to the once-bustling Bethlehem Steel mill.

Only two elderly people were in church that Thursday morning. With a demeanor of urban ministry that bides frustration, the Rev. Ronald Lord, a pleasant, middle-aged priest, bowed and blessed the congregation as though he had a full house.

Two blocks away, on a littered lot down from the corner liquor store on Steelawanna Avenue, another morning ritual was drawing a little better. About a half dozen men, most of them ex-steelworkers, were huddled there, one passing a bottle wrapped in a brown paper bag, waiting, as they said they do each morning, for someone to drive up and offer them a day’s work.

Lackawanna is a city without a pulse. It was severely stricken in October, 1983, when Bethlehem Steel “pulled the plug” on steelmaking in this one-industry town. An estimated 7,300 well-paying jobs in this city of 21,700 people went down the drain and the ripple effect took many others with them in one of the largest single industrial shutdowns in the nation.

Three generations of Lackawanna families had poured steel here for a great cross-section of American industry since 1900. Bethlehem Steel acquired Lackawanna Iron and Steel Co., the parent company, in 1922 and by the 1960s it expanded the annual steelmaking capacity there to more than 5,720,000 net tons. Lackawanna became the third largest steel producer in the world with a work force of 21,000. Company brochures say the annual payroll during the peak years reached $120,000,000.

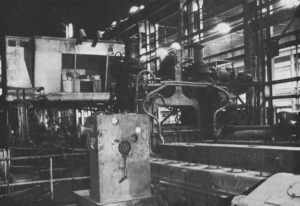

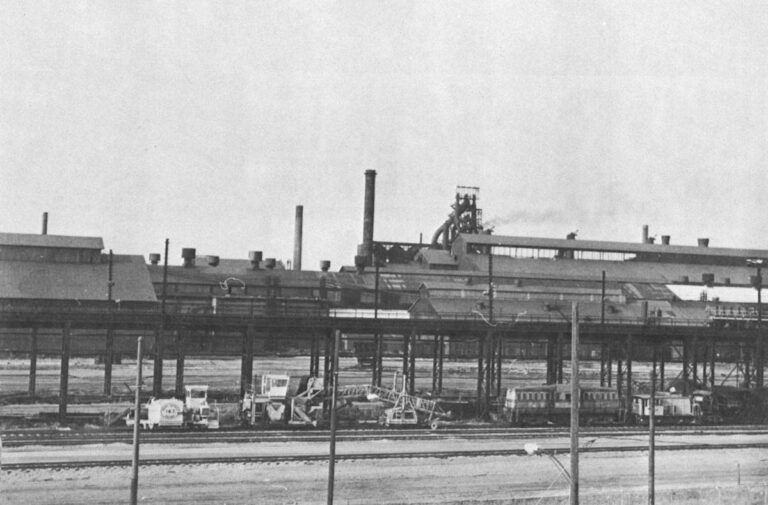

Today, the plant lies ghost-like on the shore of Lake Erie. It is an industrial corpse, a cannibalized complex of lifeless smokestacks, black buildings, motionless and empty rails. The only sign of life is at the far end, where plumes of steam rise from the coke works. Only a bar mill and the galvanizing and cold strip mills across Highway 5 still turn out steel products, from semi-finished steel shipped in from Johnstown, Pa., and Burns Harbor, Ind. The plant’s total work force is down to 1,300 and rumors abound that it may soon shrink some more.

Neither the public and private job-training programs, the federal and state subsidized lifelines, or the accelerated plans for industrial development have significantly eased Lackawanna’s deep distress. It is today the foremost single casualty of the decline of the American steel industry, and one year after the shutdown, you can feel the trauma everywhere.

“The loss of the Bethlehem Steel plant has taken away hope,” Father Lord said, sitting down to a cup of coffee after shedding his vestments. “It’s not the church I worry so much about. I feel for the men in their 40s and 50s. They thought they had a secure job for life and now find the world has caved in. Our young now either have to move out of town or give up their hopes of finding a secure job.”

“There’s no money coming in,” complained two ex-steelworkers who gave their names as Bill Rodgers, 35, and Bill Myers, also 35, when I stopped at the outdoor “unemployment lot” at Steelawanna Ave. Rodgers said he had worked in the blast furnace but was several years short of qualifying for a pension. He said he tried the federal retraining program and for a while held a job driving a school bus at minimum wage. Both men are separated from their families. Neither claims to know the whereabouts of wife or children. Each said he was barely coping with the help of welfare and the few dollars they earn when a construction or cleanup truck rolls up to hire an extra hand.

Impressions didn’t improve as I walked down Ridge Road to “the better side of the tracks.” I found gloomy people shuffling along the sidewalks, sometimes peering listlessly into store fronts and sometimes stopping to chat with others about their aches or setbacks. “For Sale” signs obscured the shrubbery in front of many homes in nearly every block. At the town library, a clerk, busy checking out books, urged this visitor not to leave without signing a petition on the main desk to protest the threat to close their library because of Erie County’s $75 million budget shortfall.

“We lost about $4.1 million a year in real estate taxes,” says Lackawanna Mayor Thomas E. Radich, himself a displaced steelworker. “For years we depended on this one industry. When it went, we had to live with less. Thirty-five people were laid off in public works…12 jobs were eliminated in the police department…8 in the fire department. People are moving out of town because they can’t find work. We know what we lost. Now we have to try to gain it back.”

Nowhere is the gloom thicker than at 650 Ridge Road, the site of the union hall. A huge “For Sale” sign was posted in front when I visited this headquarters building of the United Steelworkers of America. It once teemed with dues-paying members from four locals, but the shutdown wiped out one local entirely and reduced membership in the other three by about 95 percent.

No one manned the front desk when I walked in. The only voices came from second floor where I found Arthur Sambuchi, president of Local 2603, sitting glumly behind his desk and talking with Tom McMasters, chief grievance officer, and Wiley Cole, treasurer.

They were in mourning on this November day because of the defeat of Democrat Walter Mondale. Sambuchi said that the steelworkers worked hard to produce Erie County for Mondale, one of the few counties he won. They went bowling to celebrate after the polls closed, he said, but everyone was “sickened” when they saw the Reagan vote roll in the from elsewhere in the country.

Sambuchi, a slender man in his 40s, has a firebrand personality that earned him the reputation of being one of the toughest local presidents in the United Steelworkers union. He voted against contract concessions to the end, and virtually snarls at the mention of the Bethlehem Steel shutdown. He insists that top-heavy management and internal corporate bias against the Lackawanna plant brought about its demise.

Sambuchi becomes compassionate only when he is asked how the union members have reshaped their lives since the shutdown.

“Our membership is dying off, getting divorced, scraping jobs wherever they can find them,” he said. “One worker was found hanging at his home after his job ended.” He reeled off other horror stories, including a sad case of a steelworker named Don who was two years short of qualifying for a pension and was saddled with family medical expenses. Sambuchi said Don had to suffer the indignity of having the gas in his home turned off on the day his child died of leukemia.

“There is a lot of tragedy,” Cole added. “What the hell, even I have a close relative who had to go on welfare when his job ended, and now his wife is leaving him.”

The union reports that only about 1,100 of the 7,300 discharged workers qualified for pensions, which range from about $900 to $1200 a month, depending on length of service. The most devastated are the 6,200 mostly younger employees who are exhausting unemployment compensation and supplementary benefits.

Many un-pensioned steelworkers swallowed their pride and applied for welfare, virtually swamping the Erie County public assistance office. “In 1980, we had 23,000 public assistance cases,” says Robert Ranke, deputy commissioner of social services in Erie County. “When Bethlehem Steel started mass layoffs, home relief cases and aid to dependent children skyrocketed, reaching a high of 38,00 last April.”

A yellowing clipping posted on the bulletin board at union hall reports that the Erie County Partnership opened an office for job retraining at 609 Ridge Road, which is only a block away from USW headquarters.

Asked whether it was helping displaced steelworkers, Sambuchi shook his head. “Nobody calls us,” he said. “There is no agency that calls and says, ‘Can we help?’ “

I walked down to 609 Ridge prepared to ask what was hindering the retraining, but a stern though polite woman could read my mind. She insisted that I go to Buffalo and direct all questions to her boss, Peter Russ, director of operations for the Erie County Partnership.

Russ, a former Buffalo newspaperman, said that Erie County Partnership, a private industry council, had replaced the Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA), the government retraining program for the unemployed. He said the partnership can offer on-the-job training, with 50 percent of wages subsidized by the government. However, he admitted the program has not done much for ex-steelworkers.

Steelworkers resist retraining for jobs that usually pay $5 or $6 an hour because they were used to earning more than twice as much, he said. “Furthermore,” he added, “employers are scared of steelworkers.”

“We call up and say we have people qualified for the job orders that they want,” Russ continued. “And they tell me, ‘Don’t send me a steelworker.’ I say, ‘Well why don’t you see the man and talk to him?’ And they say, ‘I don’t want to see them…poor work habits. When they were working, they got everything they asked for. I don’t need that.’ “

His office is finding it difficult, Russ said, to offset the steelworker image: “That they got big dollars, great benefits, and the big thing was to get into a corner and go to sleep.”

He said that fewer than 50 steelworkers applied for retraining with his agency. And so the welfare load has zeroed out of sight.

The spacious parking lots that surround the stately office tower complex that used to be Bethlehem Steel’s Lackawanna headquarters are empty. All entrances are locked except at a far wing that still handles pension claims. The caretaker operations are conducted from a small soot-stained building down Highway No. 5, across the street from the idle steel plant.

R. W. Caldwell Jr., a young executive trained as a grievance officer, runs the office with the title of superintendent of the plant’s administrative services. He presents a formal front, but intense emotions surface when the conversation turns to the demise of the Lackawanna plant and what might have been if it hadn’t closed.

Concerns about the future of the Lackawanna plant first started when Bethlehem built a new, integrated steel plant at Burns Harbor, Ind. in the 1960s. They heightened as imports increased and competition from non-union mini-mills started to hurt. Bethlehem, like other major producers, found itself looking for ways to unburden costly over-capacity. It became clear that drastic reductions would occur at either the Johnstown, Pa. or the Lackawanna plants in order to utilize the capacity at the new mill at Burns Harbor.

“We in Lackawanna felt we were in competition with Johnstown for survival,” Caldwell said. “We thought we had the better plant, a more efficient operating plant, more experience metallurgically…and the newest bar mill in the industry.”

But Caldwell admits he was not surprised when he was called in from vacation on Dec. 27, 1982, for an emergency meeting with all superintendents in the general manager’s conference room. As the manager put it, the plant-by-plant analysis that the company had been making for some time resulted in the decision that there would be a major restructuring affecting Lackawanna, including the shutdown of all steelmaking. Johnstown operations were also curtailed by shifting much of its rod and wire production to Sparrows Point, Md., but steelmaking–the heart of any steel plant–was spared.

Many considerations were cited, he said. Bethlehem lost more than $100 million at Lackawanna in 1981.

Markets had shifted westward and they could be served better by Burns Harbor. Accessibility to the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence seaway no longer was the big advantage it used to be. The investment needed to replace old facilities, particularly the hot mill, was deemed too formidable.

However, many believed the ancient, cramped, and flood-ravaged plant at Johnstown had all those disadvantages and more, he said. Clearly the decision had been influenced also by other considerations within the corporate tower at Bethlehem, Pa.

Indeed, Bethlehem Steel Chairman Donald Trautlein’s announcement of the shutdown strongly suggested that the city of Lackawanna had been gouging the company on taxes. Taxes at Lackawanna have been more than five times the average amount paid per ton of shipments at Bethlehem’s five other major steel plants, he said.

Donald E. Stinner, a tax comptroller at Bethlehem headquarters, said the records show that the plant twice had been subjected to arbitrary property tax assessment increases–an $8 million jump one year and $17 million in another–with no real recourse or consideration of depressed business conditions. Stinner estimated that Bethlehem used to pay 73% of the property taxes in Lackawanna.

Bethlehem frequently warned the city that the tax inequity could kill its future in Lackawanna, Caldwell, the caretaker officer, recalls. He said the company even sent fiscal experts to advise the city on how to put its municipal affairs in shape. When their recommendations were continually ignored, Bethlehem sued the city over its tax bills for five consecutive years starting in 1978. Corporation personnel said each action seemed to be met with the attitude, “What are you going to do about it? You have too much of an investment to pull out.”

After Bethlehem shut down the steelmaking plant, Lackawanna conceded the inequity. All legal actions were settled out of court and Bethlehem’s tax bills were cut retroactively, from $13.5 million in 1982 to $9.5 million in 1983, and to $6 million in 1984. In 1985, taxes are expected to be $2.5 million.

While Bethlehem Steel had often complained about its tax treatment, it lived quietly with another problem that might have been a greater factor when tough choices had to be made. This was the plant’s notorious record of labor hostility.

Company industrial relations personnel say that more labor grievances were filed in Lackawanna than in all other Bethlehem plants combined. Caldwell said that when he began labor relations work in 1978, more than 4,500 grievances were in various levels of procedure. While most were over work rule nuances, many were petty retributions against management. (One worker filed a grievance because the company flew a 48-star flag the day after Hawaii was admitted to the union.)

Members of the more than a dozen crafts at Lackawanna jealously protected their turf by “grieving” at the slightest suspicion of intrusion, Bethlehem labor relations sources said. And nowhere, they say, were workers quicker to spot openings in antiquated work rules as a way to embellish their pay, which was already the highest in manufacturing, (For example, if a foreman carried a board across the room, a union worker was entitled to file for an extra four hours of pay because a manager technically did union work. Many blue collar workers in other plants would ignore such petty technical violations, but grievances in Lackawanna remained the sport of the day, plant people reported.)

“More often than not it was cheaper from a management standpoint just to say, ‘Give the guy four extra hours of pay’ than to fight the issue through grievance procedure,” Caldwell said.

He is one who believes that Lackawanna might have been saved–at least in the first wave of shutdowns–if work rules piled on in the bonanza era had been eased to improve productivity. “If we could have, we would have reduced crew sizes,” he said. “In almost all the mills, the crew sizes were much larger than they needed to be…I think technological changes would have come sooner and been accepted better had we had the flexibility.”

Sambuchi, of course, violently disagrees. “Give up past practices? Hell no,” he said. “We tried to give the company help on its tax problem. But past practices is what it means. We fought for them in every contract.”

As for the high rate of grievances, he said management invited them by creating unnecessary tensions. “Bethlehem Steel has 13 levels of management,” he said. He estimated that Bethlehem assigned one supervisor for every 1.9 hourly workers at Lackawanna. “That’s more than U.S. Steel or any other company. The Japanese ratio was 14-to-1 and the German ratio is 8-to-l.”

The argument is now academic, of course. No more steel is being made in Lackawanna. Nothing is in sight to replace jobs in either the numbers lost or paychecks earned. For those who remain, the tax burden is punishing. Even with drastic retrenchments, city taxes are up 29 percent. Even with dwindling school populations, school taxes have shot up 40 percent. And even with the stiffest belt-tightening by Ed Rutkowski, Erie County’s respected executive, the loss of revenues from Bethlehem Steel is an important reason why Erie County was forced to ask the legislature for new taxing limits to meet mandated programs and overcome a staggering budget shortfall.

Meanwhile, the young desert the town which their parents and grandparents had built. Population has dropped from 28,000 in 1970 to 22,700 today. Neighborhoods disintegrate as once-proud families sell their homes at bargain basement prices. Speculators buy them up with a minimum down and then milk them as rental properties. Plans for renewal offer stunning blueprints but major developers do not respond.

Only the renown Our Lady of Victory Basilica, built by Lackawanna’s most famous resident, the late Father Nelson Baker, seems unchanged.

“It is traumatic for a lot of us to see the young go,” says Ruth Cullen, parish secretary, who is a widow of a steelworker. “But when you have difficult times, a lot of people turn to the church. Only two bingo games in town have had to close down. And collections at the shrine and the candles lit have increased.”

With its excellent access to Lake Erie, Lackawanna has better than average resources to offer new employers. No one yet has a clear prescription for recovery, but the lessons in distress should be clear enough. Whatever the world economic forces that staggered the American steel industry and however shortsighted certain management decisions may have been, the community of Lackawanna cannot escape a measure of blame for its industrial collapse.

Unfortunately, the contributions of the hardy breed of dedicated worker who once made Lackawanna a steelmaking capital are too easily forgotten in today’s postmortems. What stands out is unremitting labor hostility inconsistent with union leadership demanded by the times. So does the local government’s taxing insensitivity to an industry that fueled its economy for so long. Whether deserved or not, both add up to a bad business climate that haunts the city fully as much as its empty buildings.

©1985 John Strohmeyer

John Strohmeyer, editor and vice-president of the Bethlehem (Pa.) Globe-Times for 28 years, is chronicling a steel company’s battle to survive.