Leonard Downie

- 1971

Fellowship Title:

- Urban Development in the U.S. and Europe

Fellowship Year:

- 1971

The Modern Sack of Rome

Rather than the usual gaggle of tourists, the crowd moving up Michelangelo’s monumental steps to the top of Capitoline Hill in the heart of Rome on a recent wintry night was made up of several hundred ragged men, women and children representative of the estimated 60,000 residents of suburban shanty towns surrounding the Italian capital. This particular group of families had been moved by the government out of a squalid slum in Pietralata, on the eastern edge of Rome, to only slightly better “provisional” quarters in nearby army barracks originally built for Fascist troops before World War II. They had gone to Capitoline Hill to take their plea for better, permanent housing directly to Rome’s mayor and city council. Stairs to the Campidoglio. Just before midnight, as the council neared the end of debate on a long-stalled plan for coordinated development of Rome’s metropolitan area, about 100 of the protestors outside burst into the town hall and began shouting their complaints and demands at startled council members. The disturbance, which included some scuffling between the

Israel’s Second Generation New Towns

For many tourists and resident foreigners, Jerusalem is the place to be in Israel. Among the countless emotional touchstones and historical reminders in and around its ancient walled “old city” are important shrines of three major religions: the excavated western (“wailing”) wall of the Hebrews’ second temple; the Moslems’ golden-domed Mosque of Omar over the rook on which Mohammed is said to have ascended into Heaven; and the various places where Jesus was tried, forced to carry the cross, crucified and buried. Inside the traditional “Jewish quarter” of the old city and on the hills of eastern Jerusalem that overlook it – all of which was captured by the Israelis from Jordan during the 1967 war – historic old buildings are being remodeled and modern highrises are being constructed, mostly to provide luxurious hotels and “second home” apartments for wealthy foreigners, many of them Americans. The rest of Jerusalem also continues to grow vigorously (and, some fear, too rapidly) as the capital of Israel and world center of Jewish culture, with new government offices, museums,

Israel Builds

Tel Aviv, Israel December, 1971 Under a warm winter sun, Bedouin tribesmen in layered dark flowing robes, with long curved knives dangling from their belts, hurry about their business in the busy streets of the old town of Beersheva, the gateway to the Negev desert, much as generations of their forebearers have done before them. In this modern day, the Bedouins, who still come to town leading caravans of camels to the early morning market, cross paths with bankers, shopkeepers, college students, desert scientists, ever-increasing numbers of tourists, and ubiquitous uniformed Israeli soldiers, the young women in distractingly short olive green skirts and the young men carrying their automatic rifles as casually as the Bedouins wear their knives, setting the guns down on snack bar counters as one might an umbrella. Despite the souvenir shops, travel agencies, banks, offices and department stores crowded into its small buildings, the old town center of Beersheva still resembles a frontier town. For perhaps 4000 years, at least, the town’s site, with its plentiful underground water and a

Two New Town Mirages

Washington, D.C. November, 1971 They are the most unlikely of locations: a remote hot, dry Arizona moonscape of dusty, rocky hills and dark, foreboding treeless mountains around a long forgotten reservoir lake on the Colorado River at the California border; and 500 miles away, a once lifeless below-sea-level marsh and salt pond jutting from the San Francisco peninsula into the bay south of San Francisco in teeming San Mateo County, California. On these sites, two of the most audacious, ambitious, highly publicized and personalized versions of the “new town” concept in the United States are being built. Begun in 1963 on the desolate eastern shore of meandering man-made Lake Havasu, Lake Havasu City, Arizona, is where the much bally-hooed reconstruction of old London Bridge in the desert was recently climaxed by a dedication dinner for American and British celebrities and newsmen in a huge tent atop the bridge itself in the 100-degree heat of an early October Saturday. From there, visitors could look up at desert hillsides criss-crossed by newly cut streets and

The Santa Clara Valley’s -“Appointment with Destiny”

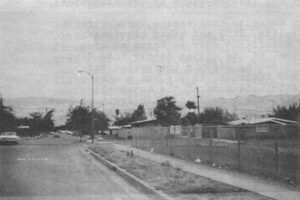

San Jose, California October, 1971 Eye-smarting, mustard-colored haze hides all but the shadowy outlines of the mountains on each side of the long, flat valley. Automobiles push and shove through crowded concrete and neon strips of stores, service stations, car lots and taco stands. Here and there, small isolated groves of the last surviving fruit trees fight strangulation by the surrounding subdivisions, factories and freeways. Acres of roofed box houses huddle tightly together, back to back and side to side, without open spaces, parks or even sidewalks. Many tattered homes just ten years old slouch in ready-built slums, their gravel roofs leaking, concrete slab foundations cracked, flimsy veneer doors and walls warped, stick fences rotting and sparse dirt yards alternately flooding and heaving. The fulfillment of the Santa Clara Valley’s “appointment with destiny”: sixteen cities of roofed boxes and concrete strips wrapped around each other with no sense of community or vestige of natural beauty. Looking north, note the San Francisco Bay at top left and mountain ridge at top right. A visitor’s first impressions