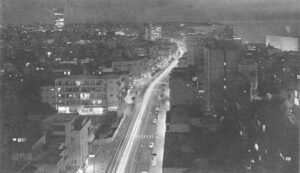

For many tourists and resident foreigners, Jerusalem is the place to be in Israel. Among the countless emotional touchstones and historical reminders in and around its ancient walled “old city” are important shrines of three major religions: the excavated western (“wailing”) wall of the Hebrews’ second temple; the Moslems’ golden-domed Mosque of Omar over the rook on which Mohammed is said to have ascended into Heaven; and the various places where Jesus was tried, forced to carry the cross, crucified and buried. Inside the traditional “Jewish quarter” of the old city and on the hills of eastern Jerusalem that overlook it – all of which was captured by the Israelis from Jordan during the 1967 war – historic old buildings are being remodeled and modern highrises are being constructed, mostly to provide luxurious hotels and “second home” apartments for wealthy foreigners, many of them Americans. The rest of Jerusalem also continues to grow vigorously (and, some fear, too rapidly) as the capital of Israel and world center of Jewish culture, with new government offices, museums, archives, university buildings and suburban residential communities.

East Jerusalem: Walled old city and domed Mosque of Omar are in center background near horizon; hills on which new luxury hotels and apartments are to be built are on the right.

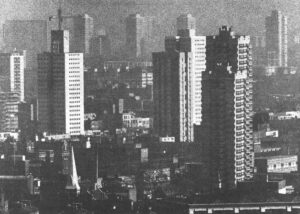

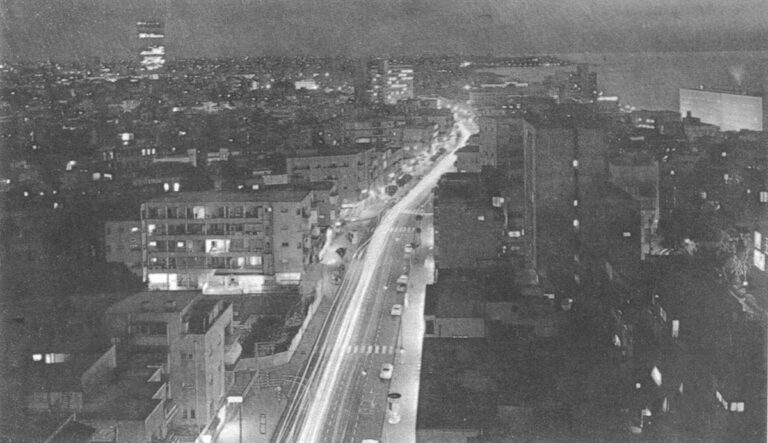

But for an overwhelming number of urban Israelis, whose emotional attachment to Jerusalem is undeniable, Tel Aviv and Haifa on the Mediterranean coast are the places in which to live. Despite the polluted haze of industrial smoke that often hangs over Haifa’s harbor, and the noisy traffic, Miami Beach-like seaside hotels and monotonous suburbs of Tel Aviv, Israel’s two largest communities still offer much of what has always made urban living desirable in the favored cities of the world.

In Tel Aviv, there are the countless crowded sidewalk cafes on Dizengoff Street, the public promenades and beaches along the Mediterranean Sea, the bookstores, varied shops and open air food stands and European bakeries of Allenby Street, the sprawling Carmel food market and Oriental bazaars in the maze of narrow old lanes in the Yemenite quarter, the great variety of restaurants, theaters and nighttime activities throughout the central area, and the tree-lined streets and parks for strollers almost everywhere in the city. Most major avenues and centers of activity are surrounded by places where people live. As a result, even in the suburbs, shops of every kind are located just downstairs or down the street from one’s apartment, green places where the children can go are nearby, and the sidewalks are alive day and night with people.

In Haifa, a smaller, quieter city, the reknowned flora of the upper class neighborhoods on the ridges of Mount Carmel trails down its sides and fills even the central business, shopping and residential districts just above the harbor. Streets of shops and homes wind around each other on the green hillsides, connected vertically by picturesque stairways and walks that are bordered by narrow rows of shops and trees on some levels, and that open into wide vistas on others. Haifa is often compared to San Francisco; it has a similarly spectacular setting overlooking a bay and a pleasant, active center on a pedestrian scale.

Israeli government planners are now trying to recreate the attractive characteristics of cities like Tel Aviv and Haifa in the new towns being built in the country’s interior. From two decades of trial-and-error building for the great numbers of arriving immigrants have evolved functionally integrated neighborhoods of housing, stores, offices and government services that, in miniature, are not so very unlike established areas in the large cities. In fact, the best of these new town neighborhoods are more conveniently arranged for pedestrians and more imaginative in design than their big city counterparts. But they are still only small, isolated parts of otherwise confused and sterile developments that continue to suffer from their beginnings as loose, inefficient “garden city” collections of barracks-like housing segregated from sparse commercial and government centers by overly generous, barren open spaces. Much of the commercial diversity, cultural activities and social excitement of satisfying city life is still missing. To try to solve this problem the government has begun building a few more projects in which the planners have applied from the very beginning on a town-wide (rather than neighborhood) scale what they believed they had learned about building truly urban places on a manageable human scale. These more recent projects can be considered a “second generation” of new towns in Israel.

“We can’t really build a town yet,” insisted Baruch Venger, a Ministry of Housing employee who helped launch the new town of Karmiel, and is now its mayor. Karmiel, located thirty miles by car northeast of Haifa in hilly central Galilee, is the newest, most experimental and most closely watched of the second generation new towns. It is now beginning the struggle to transform itself from a growing collection of carefully pieced together physical parts into a real community breathing life of its own.

“We can build houses for people,” Venger told me, as he explained the experiments in architecture and building construction that are taking generally pleasing shapes at Karmiel. “But the problem,” he added, “is how to build a new society.”

How indeed can a government or any other single force create in one stroke not just the hardware of a city, no matter how attractive that may be, but also the satisfying, self-perpetuating exuberance of life that makes cities like Tel Aviv and Haifa desirable places in which to dwell? This, of course, is the basic problem confronting builders of “new towns” all over the world today. Few, however, have faced it so frankly with as much understanding so soon as has Israel. From the very beginning, it has been forced to build wholly independent new communities scattered throughout the country. Because of their physical isolation these communities must become socially self-sustaining entities to survive, rather than dependent satellites of existing large cities. As a result, Israel has become a pioneer in experimenting with the effects of land use, architecture, traffic patterns, acclimation and other social factors.

Israel’s second generation of new towns merit close study for this reason, even though they lag behind contemporary projects in the United States and, especially, Europe in the progress being made in controlling pollution, disposing of wastes, burying and servicing utility lines, utilizing telecommunications and the like. Israel, burdened once again by the task of housing an immense number of new immigrants (currently from the Soviet Union) and still preoccupied financially with defense, does not yet have the time or money for these technological experiments. Despite the possibly dire future consequences, it still must build fast. Its greatest need, in addition to a sheer numerical increase in housing units, is the creation of socially workable new communities that will bring together immigrants and “veteran” Israelis, and attract more people away from Tel Aviv and Haifa to help better balance the country’s population distribution.

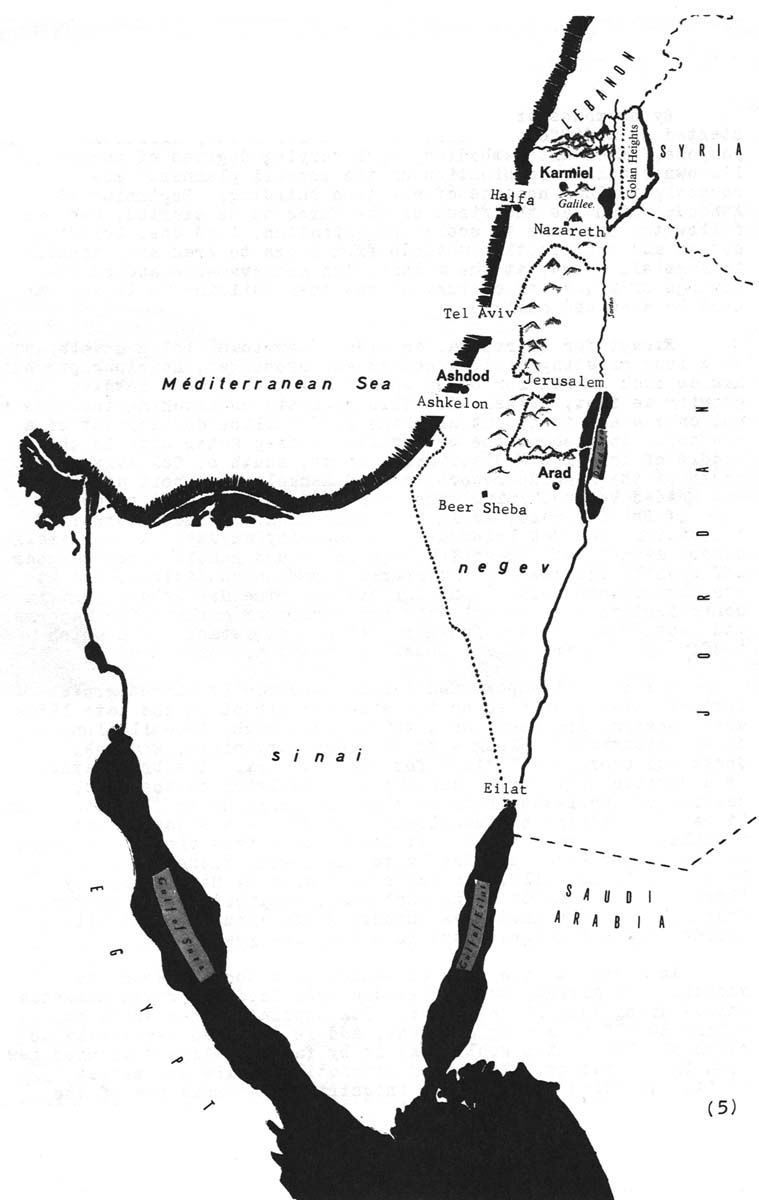

Although there are thirty new towns in various stages of development in Israel, three projects stand out from the others as particularly belonging to a new generation in planning and execution: Ashdod, the new seaport on the Mediterranean south of Tel Aviv; Arad, a new resting place for tourists in the Wilderness of Judah overlooking the Dead Sea and the home of workers exploiting the mineral and chemical wealth of both the Dead Sea and the Negev Desert; and Karmiel, put down arbitrarily in the middle of the Galilee hills to concentrate more Jews in a region heavily populated with Israeli Arabs, and to provide not too far from the coast, in a scenic setting with an agreeable climate, a new magnet to draw population and industry away from the crowded areas.

Each of the three towns, although still in the early stages of its projected development, already possesses an identity of its own, a particular sense of place that is missing in most of the monotonous first generation new towns. Each also has a much better reputation among the Israelis than did the earlier projects, most of which are still derided as “immigrant towns.” A mechanic living in a suburb of Tel Aviv, for instance, has been north to see Karmiel and would move there if he found the right job. A young woman working in the aircraft industry in Tel Aviv has heard from her friends that Arad is a “together” place to which young Israeli families are moving and staying. A survey of Ashdod residents showed that an unusually high percentage – three of every four families, including immigrants and veteran Israelis – plan to make that fast-growing city their permanent home.

ISRAEL: the three “second generation” new towns: Karmiel in cintral Galilee in the north; Ashdod, the new seaport just south of Tel Aviv; and Arad, in the Negev near the Dead Sea.

By no means are all three projects the same. Each was started at a different time, and each for a very different purpose. Each also embodies, with varying degrees of success, its own peculiar combination of the Israeli planners’ most recently refined notions of new town building. Beginning at Ashdod, which was the first of the three to be started, one can follow the progress in social organization, land use, building design and construction methods from there to Arad and, finally, to Karmiel, where, at the moment, the achievements and shortcomings of a quarter century of new town building in Israel can best be seen and analyzed.

Except for Beersheva, an older “new town” being developed at a long existing trading center and crossroad, no other project has as much reason for being where it is, and, as a result, is growing as fast, as Ashdod. This igantic undertaking includes not only a new town, but also the $120 million development of a new port, located on the best suitable deep water site in the middle of Israel’s Mediterranean coast, south of Tel Aviv and north of the seaside resort town of Ashkelon. A port at Ashdod was needed because Haifa, the country’s leading port since the days of British rule, is in an inconvenient northern corner of the nation, and was being used to capacity anyway. A much smaller harbor at old Jaffa near Tel Aviv could not handle large cargoes efficiently because of unfavorable shoreline conditions, and it was closed when Ashdod’s harbor opened. The new Ashdod port is convenient to the big Tel Aviv and Jerusalem markets for imports, and much closer to the southern regions of Israel, from which “Jaffa” citrus fruits and desert minerals are exported.

Nothing but empty sand dunes, bordered by citrus groves further inland, existed on the site for Ashdod in the late 1950s when construction began on a thirty-foot high, two-mile long curved breakwater, along with the necessary piers, wharves, docks and storage buildings for the new port. The breakwater is a notable engineering achievement involving on-the-beach casting of underwater support piers weighing up to forty tons each. It is today a kind of functional sculpture – a sweeping arc reaching out into the sea. It can be seen from almost any point on the higher land immediately to the south, where the city itself is being built. Ashdod’s port already handles nearly three million tons of cargo each year, compared to the nearly four million tons that move through Haifa annually. It will become Israel’s largest port in a very few years.

ASHDOD, in 1963 – Construction on the new port and town on what had been empty sand dunes. The beginning of its great arcing breakwater can be seen in the lower right.

(The smaller, L-shaped breakwater in center is for construction purposes only.)

(Israeli government photo)

As a result, the city of Ashdod is a booming economic success. It already has achieved a self-feeding growth momentum unique among Israeli new towns. Its population has grown to nearly 50,000 in a single decade, and is expected eventually to reach 350,000, which would make it by far the biggest planned new town in the nation. Its chief attraction is the job market of its expanding port and the industries that make use of the raw materials unloaded there. These jobs and their good pay, as well as all the ancillary business opportunities of a boom town, also have attracted a large number of native Israelis (Sabras) and older European immigrants to join the African and Middle Eastern newcomers who furnished most of the labor during the port’s first years of growth.

These factors have had a great influence on the progress of Ashdod as a planned community. The government has had to expend little effort to attract employers, commercial activity, or the variety of residents needed to create the bustle of city life that has often been in short supply in new town projects in the hinterland. And although the government has built more housing in Ashdod, because of its size, than anywhere else in the country, private developers also have found a lucrative market there and are building entire neighborhoods themselves. They are aiming in particular for Ashdod’s unusual new town market of higher income Israelis and American and European immigrant families. A sign outside one recently completed residential tower standing on concrete stilts on a hill overlooking the sea advertised “exclusive, American-style apartments” with central radio and television antenna hookups, central heating (still a relative luxury in Israel) and private parking. On other hillside locations near the beach are growing neighborhoods of detached single-family houses, some of them also built in expensive, roomy, American styles on large lots.

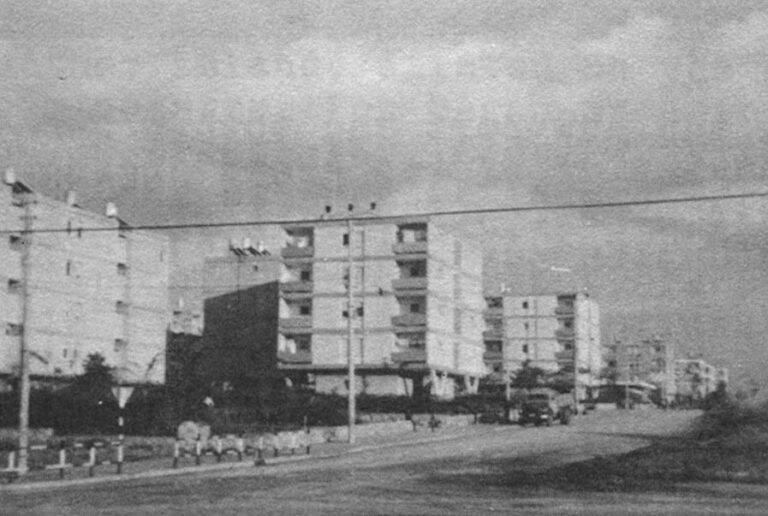

Ashdod’s very dynamism, however, and the growing role of private developers there, do create some problems. Although the city is being built according to a rather rigid overall land use plan (which places heavy industry to the north of the docks, for instance, so that winds from the sea blow industrial smoke and odors away from the rest of the city to the south), it is immediately obvious that widely differing amounts of care are being taken in the layout and construction of various residential blocks. The single-family homes and luxury apartment houses are being crafted attractively and solidly for higher income families. But in some other areas of town on lower ground, block after monotonous block is filled with apartment boxes that look like “immigrant” town “public housing,” although, ironically, much of it has been built by private developers. No experiments in placing veteran Israelis alongside immigrants of various backgrounds, or putting upper and lower income families together, are being tried in Ashdod. Its primary concern is growth. Yet, even its duller areas benefit from the lush vegetation everywhere, the parks leading to the public beach that will border the entire city along the sea, the unusually lively commercial center of each quarter, and Ashdod’s overall prosperity. Government surveys show that the only dissatisfied residents there are those who believe their jobs and pay are not as good as the next fellow’s.

Three faces of Ashdod:

expensive, American-style single-family home on large lot near the beach

rows of rather monotonous but well-constructed apartment boxes

abundance of greenery surrounding a pedestrian walk and playground between apartment buildings.

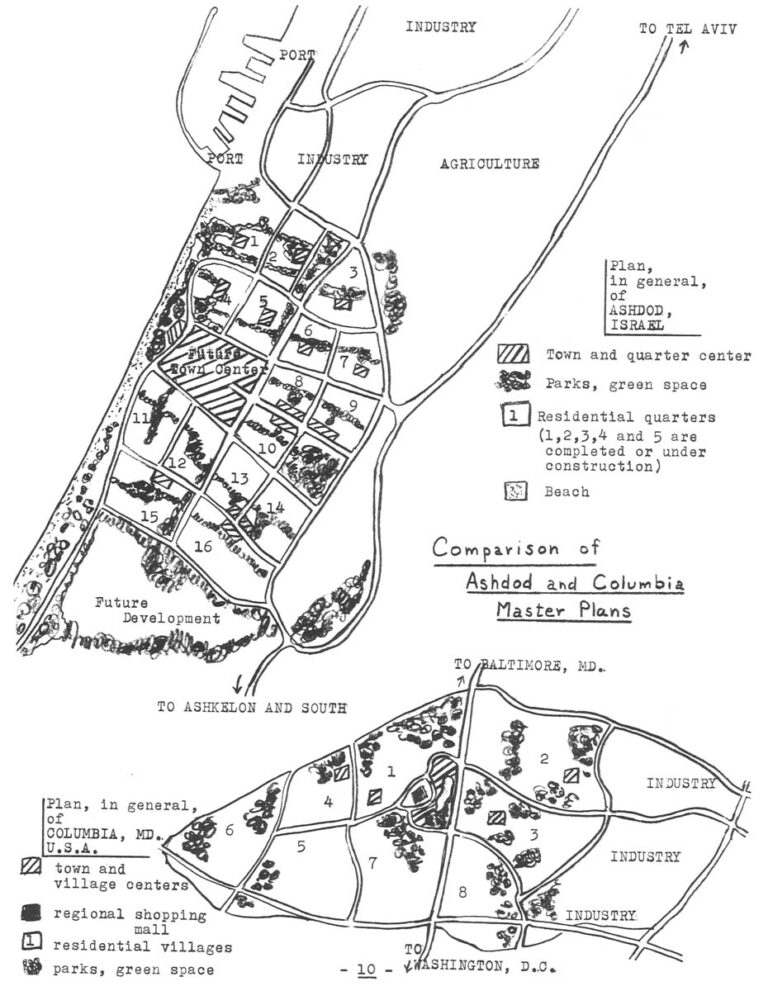

The “American style” apartments and suburban single-family homes for the middle class are the most telling clue to Ashdod’s place in the progress of new town building in Israel. Its overall land use plan is generally like that of the projects considered to be “new towns” that are now being built primarily for middle class families in the United States, and particularly like the plan for Columbia, Maryland. Like Columbia, Ashdod essentially is being built in several “villages” grouped roughly in a circle around a “downtown” city center. Like the villages of Columbia, each “quarter” of Ashdod also has its own subcenter of shopping, offices, government services and clinics, restaurants, cinema and the like. Large boulevards carry the mainstream of auto traffic around the outside of the city and through it on a few major axes, with limited access loops reaching into each village, in a pattern almost exactly like that for Columbia. This road network is supplemented inside each village in both Ashdod and Columbia with pedestrian ways that lead from homes and apartments to schools, some stores, parks and recreation areas.

Both Columbia and Ashdod are essentially compromises between suburb and city. Each has built-up areas of city-like density with walks and congregating places for pedestrians, but these focal points are essentially “shopping centers” around which the residential satellites revolve. The most efficient way to get to and from the centers, especially from the more distant residential areas, is by automobile along the efficiently planned avenues. These roadways, and not the pedestrian paths of the villages, are the real arteries of both new towns, even though far fewer Ashdod residents, like Israelis generally, own cars than do the middle class families of Columbia, Maryland.

In Columbia, as in the older new towns of Israel, an attempt was made to spot a few convenience stores, an elementary school and recreational facilities in each smaller grouping of residential units that together form the circle around each village center. In Columbia, each village is broken down into several of these smaller neighborhoods, and each is supposed to be an almost autonomous unit on a pedestrian scale with a psychological unity of its own. Some planners now point out, however, that although children in these neighborhoods may congregate in the schools and on the playgrounds, the adults in the neighborhoods of both Columbia and the first generation of Israeli new towns still gravitate toward the village or town center, where the action is, if it is to be found at all. Even the middle class adults who are getting away from crowded city life in pastoral green suburbia in the United States go as often as they can to the nearest big shopping mall to mingle with other people and enjoy whatever color and variety are there.

Comparison of Ashdod and Columbia Master Plans.

What became clear to Israeli planners, as has been obvious for some time in the United States, is that the only “unifying” factor of suburban or “new town” neighborhoods is similarity in economic and social strata. Families tend to group themselves as residents of a neighborhood of $30,000 split-level houses in Columbia, or as a group of “veteran” Israeli or European immigrant families in the better neighborhoods of an Israeli new town. The growing determination of the Israeli government to integrate older residents and immigrants of all backgrounds and income groups was simply not being fostered, as many planners had hoped, by dividing new towns into decisively separated residential neighborhoods, each of which was supposed to grow into an integrated, homey unit. The physical division only prevented the entire town from ever becoming a cohesive community.

As a result, its residents were unable to find the satisfactions of urban living in either the limited facilities of their own neighborhood or the too distant town center. The commerce of the town center and the stores of the neighborhoods needlessly duplicated each other. Depending on the peculiar circumstances of each town, either the neighborhood storefronts stood empty as residents somehow made their way to the better stocked, more varied center, or the town center remained under-used because it was too inconvenient for car-less families to reach frequently.

In Ashdod, one can see the first tentative move away from this dilemma in Israeli new towns, which is one basic difference between it and Columbia, Maryland, and other American new town projects. The larger residential quarters of Ashdod (of which there will eventually be sixteen, each containing about 20,000 people – compared to the 15,000 population of each of Columbia’s planned seven villages) replaced smaller neighborhoods (each of which contain only a few hundred families in Columbia) as the primary planning units. This gives each family a larger universe within pedestrian access of his front door. Each quarter can thus support much more than a few stores, a school and a playground or two. In fact, the center of each of the first two completed quarters in Ashdod is larger, livelier and more varied than many of the entire town centers of first generation new towns in Israel. Because each center also has apartments mixed well with the scores of stores and offices, it constitutes a more natural, around-the-clock urban place than even the “downtown” of Columbia, which in reality is a few office buildings and a large covered shopping mall surrounded by parking lots and major auto arteries that cut it off from the places where people live.

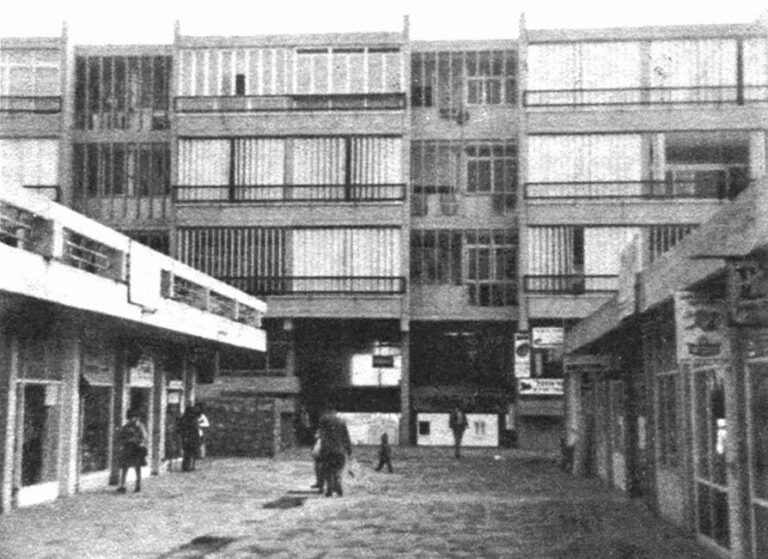

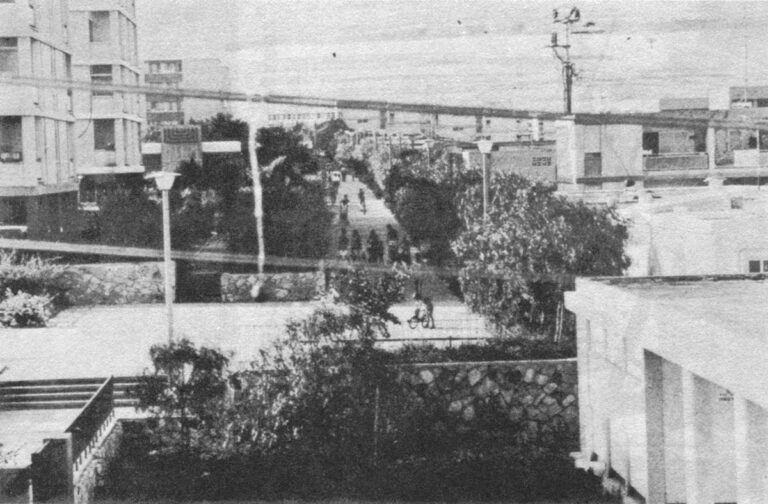

Within the limited confines of the two-block square center of the first quarter of Ashdod, one is almost back on the streets of Tel Aviv. It is not a boxy shopping mall inside, but rather a criss-crossing of pedestrian streets and small plazas that go up and down, under cover and out in the open, in and around irregularly placed and shaped buildings containing apartments, stores, offices, cafes. There are department store, appliance and sporting goods shops, foodstores, bakeries, dry cleaners, real estate offices, and even a “unisex boutique.” People are coming and going in every direction, or simply sitting outside enjoying the winter Mediterranean sun in the numerous sidewalk cafes. Shopping housewives mingle with workers on their lunch hour. Even the gaudy signs on some shops, many of which would be banned as nonconforming in Columbia, Maryland, add to the color of life there.

Center of residential quarter in Ashdod:

Inside the commercial center, looking both ways along a wide pedestrian street, off which others run in and around stores, offices and apartments. Note in center of both photos three-story apartment segment.

The people are undeniably working class men and women, the real builders of any port or industrial city. Here and there, one hears French spoken by the numerous North African Jewish immigrants. Something more is being built for them in Ashod than the old European or American factory town, or the “immigrant towns” elsewhere in Israel. In Ashdod, they have lively gathering places, somewhat better housing, the beach along the sea and attractive parks – like the one that begins immediately across the main street from the commercial center of the first quarter, with a flagstone terrace overlooking the sea, and continues down a long slope of grass, pine and palm trees and tropical plants to the beach.

But for the executives working in Ashdod, the new town is still far from being their idea of a cosmopolitan place. Many of them are commuters who go to Tel Aviv for entertainment, the arts, and other aspects of big city life. Their homes are either in Tel Aviv or in the suburban neighborhoods of large houses in Ashkelon, the summer beach resort less than a half hour drive south of Ashdod.

Because Ashdod has no single “downtown” at present, necessary governmental functions have been parceled out in temporary locations in the various centers of the residential quarters. As a result, the city lacks overall cohesiveness in that disturbing way that Israel’s older new towns and most meandering American suburbs do.

A big city downtown is supposed to be built eventually in Ashdod. An ambitious design selected in a national competition would place government buildings, public halls, hotels, stores and apartments around plazas in tiers that would step down to a seaside cultural center and park. The architect’s model is impressive, but construction cannot begin for years, until many more residential quarters around the downtown site are completed. Even then, realization of so large an undertaking depends on the interest that can be generated among prospective private tenants and investors. One wonders if there will be sufficient interest if too many of Ashdod’s higher wage earners are already accustomed to spending their non-working hours in Tel Aviv and Ashkelon. Perhaps there will be, but only because of Ashdod’s overall rapid growth and unusual economic potential as a large port.

How, then, can suitably lively, and expensive, centers be created for much slower growing, less dynamic new towns? This problem has long vexed new town builders in Europe and the United States too. In eight-year-old Foster City, California, near San Francisco, for example, the residential areas are more than half finished and occupied, yet there still is nothing but dirt covering the huge plot designated by an old sign as the “future town center.” For years, the residents of Columbia, Maryland, which is clearly the most advanced American new towm project, had to drive to either Baltimore or Washington, D.C., each about thirty miles away, to find a department store, first-run movie or the speciality shops that middle class shoppers dote on. Only last summer did the first section of Columbia’s new covered shopping mall open. It turned out to be quite different from what had been began as a more varied “downtown” of stores, offices and hotels in a setting on the shore of a lake that would have fit in well with what had been evolving as the “personality” of Columbia. Only three office buildings, all used by Columbia’s developer, have been built on that site. Merchandisers were more interested in development of a “regional” covered mall center that they believed suburbanites would want, with a surrounding sea of parking for shoppers driving from greater distances beyond Columbia itself. The existing center is certainly used, and welcomed for what it contains, by Columbia residents. But it is out of touch with their homes by foot and no more a part of Columbia psychologically than if it were any one of several similar malls in the Washington or Baltimore areas.

An alternative approach – building an attractive, expensive center first, fitting it in with surrounding residential neighborhoods – was tried in Reston, Virginia, south of Washington, D.C. Exceptionally well-designed apartment buildings and combinations of shops and apartments were carefully placed around man-made Lake Anne at the bottom of a bowl of low hills. Lake Anne Center immediately won national praise for its architectural and natural beauty. However, the center’s great initial cost helped bankrupt Reston’s original developer, Robert Simon, and forced the scuttling of much of his more daring plans when his financial backer, Gulf Oil Corporation, took over the project.

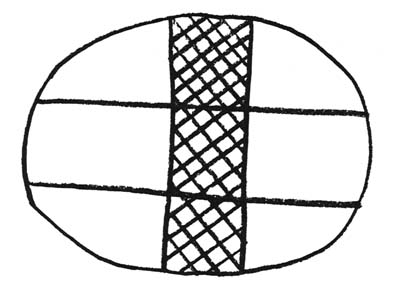

What Israeli planners wanted was a town center that would grow proportionately with the project itself, and not a heart to be put in after the body had grown almost to maturity. They also wanted to spread the expense out over the time it took to build the entire project, rather than putting up a huge sum at either the very beginning or very end of development. To try to accomplish this, they turned to a concept that, once again, seemingly mirrors the way “unplanned” cities have always grown naturally: the linear center.

Instead of being a point in the middle of a circular community deeign, the linear center becomes the spine of the city, growing longer as the residential neighborhoods alongside it grow. As each stage of residential development is completed, so too is a parallel section of the city center with all the services needed for a population that size. Until the project has grown very large and outlying neighborhoods are built, the center is never very far, even by foot, from most of the homes in the neighborhoods alongside it. Less duplication of commercial facilities, except for daily needs, would then take place in the residential areas themselves. Yet life in them still benefits from the nearby urban activity of the center, and its economic activity is stimulated, in turn, by its easy accessibility to most residents. The diverse functions of the city – housing, commerce, education, recreation, government and other activities – are more closely intertwined with one another.

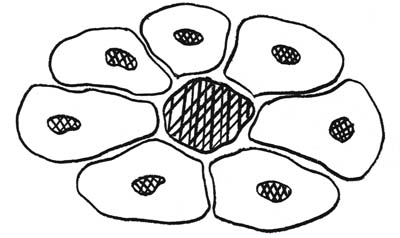

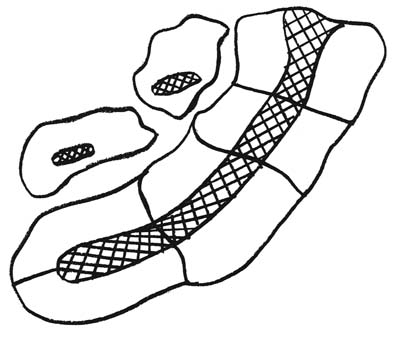

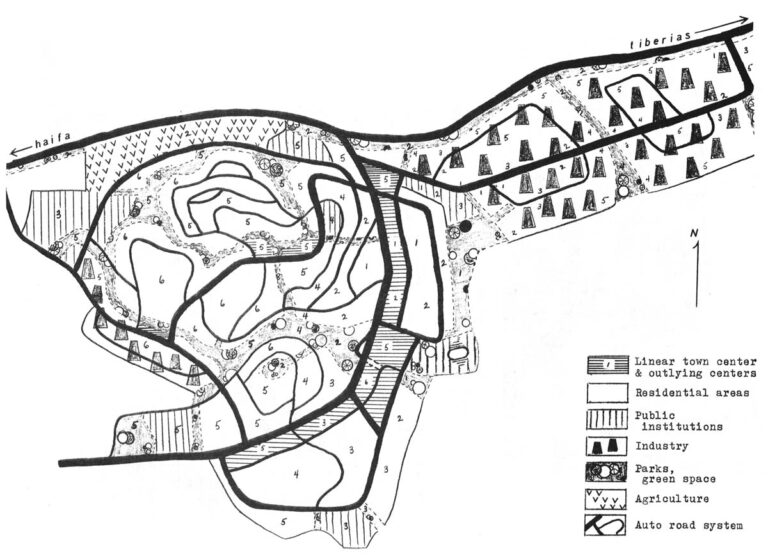

Evolution of Linear Center Concept

Plan, in principle, of new towns like Ashdod, Israel, and Columbia, Maryland

Plan for Arad, Israel

Plan for Karmiel, Israel.

In Columbia, Maryland, and Ashdod, Israel, and most other past new town projects in the U.S., England, Europe and Israel, a circular group of residential villages or quarters, each with its own commercial center, is grouped around a “downtown” city center, which usually is not built, however, until most of the surrounding city is completed.

In Arad, Israel, each section of the linear city center that bisects the new town is built along with the adjacent residential quarters. Each quarter does not need its own center, as a result, and at each stage of development, there is sufficient “downtown” for the number of residents.

In Karmiel, Israel, the linear center is considerably enlarged to become the true “spine” of the city. Each section of the center also is to be built along with the corresponding residential quarter. Only outlying neighborhoods (built on hillsides here) will have their own subcenters.

The great avenues of the world’s large cities have always been, after all, linear activity centers for the residential areas around them. The function they serve in carrying pedestrian and auto traffic through their areas can easily be duplicated by a new town linear center. In addition, new towns have an opportunity to keep cars on separate axes, away from pedestrians, who can be given their own grand avenue through the middle of the center, and easy access to it from their homes by passageways above or below the automobile traffic arteries. The builders of one American new town, Park Forest South, Illinois, near Chicago, believe that it also would be easier and more economical for public transportation to be built along a linear center (See LD-1; The Midwest: An Unlikely Laboratory for New Towns). A single such line could reach as many people and functions as several built on radii from the edges to the point center of a circular new town. This is one of several other reasons that they have planned a linear center for their project.

Park Forest South is just beginning to build. The linear center concept has been tried elsewhere only in limited ways in a few new town projects in Scotland and the Soviet Union. Israeli planners, therefore, were the first to make it the predominate physical and psychological theme of a new town and, at the same time, eliminate decisively separated individual neighborhoods and quarters with competing subcenters of their own.

As it happened, the first Israeli project planned with a linear center, Arad, used the concept as much for climatic reasons as any other. The hard lessons of Beersheva, originally planned as a spacious low-density suburban “garden city” that did not wear well in the wind and sun of the Negev desert, dictated that Arad be more suitably designed for its even more remote location on a high, exposed desert plateau on the edge of the Negev, where the Wilderness of Judah begins alongside the Dead Sea.

As illogical as Arad’s location may seem at first, there were definite reasons for its selection. Although the barren wilderness around Arad supports almost no natural vegetation, it does contain hidden treasures: phosphate for fertilizers, natural white cement and marble for building materials, and a wealth of minerals in the stagnant water of the Dead Sea. These are all processed at nearby factories in the desert. A new petro-chemical plant also was put in the area, far from the country’s large population centers, which it might otherwise further contaminate. The plateau site picked for Arad is convenient enough to these enterprises, and, at the same time, relatively accessible to the rest of the nation by highways over the gradually ascending hills leading to the new town from the west.

On the other side of Arad, the plateau falls away sharply to the east in a series of steep hills reaching the flat shoreline of the Dead Sea, 3300 feet below Arad and 1300 feet below sea level. From a vantage point just a few miles east of Arad’s center, one can look out over the spectacularly rugged hills to the eerily still green-blue Dead Sea and mountains of Jordan beyond it. It is at this spot that Arad’s resort area for tourists is being built (two hotels and restaurants are there already), adding more jobs and revenue to the town’s economy. Recently improved roads wind from there down to the Dead Sea shore and “beaches” and further to the site of ancient Sodom to the South. A new road north also takes tourists to the recently excavated mountaintop palace-fortress of Massada, built by Herod as a retreat and later besieged and captured by Roman legions from the last zealot Jewish holdouts of a revolt against Rome 1900 years ago.

In some respects, Arad’s climate is as agreeable as it could be in the desert. Its summer temperatures are about the same as Beersheva’s, averaging 80 to 90 degrees, and its lofty location benefits from cooling breezes. But it is exposed to steady sun radiation and occasionally vicious high winds carrying cutting dust and sand from the desert. Drinking water is nowhere in the area.

The planning team for Arad was charged with designing a city protected from the dangers and unpleasant aspects of the climate and yet “open” enough to and in harmony with the severe natural beauty and vistas of the area.

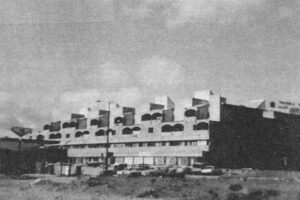

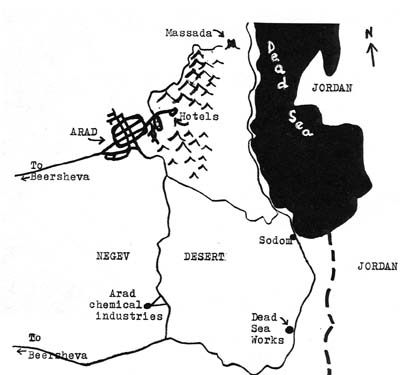

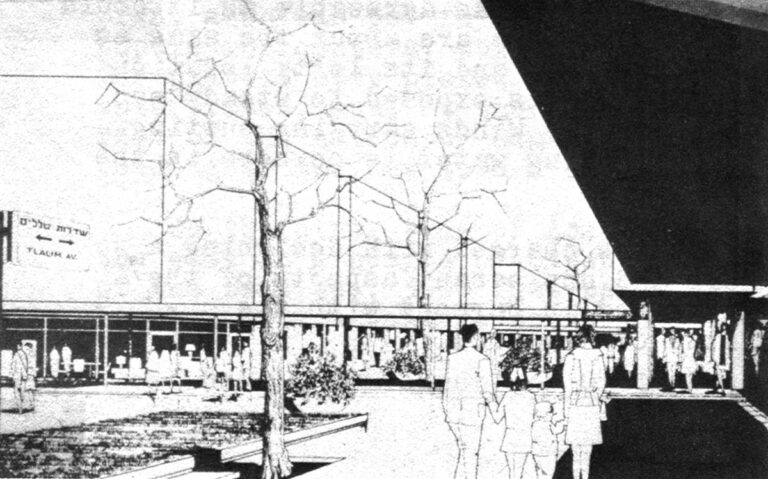

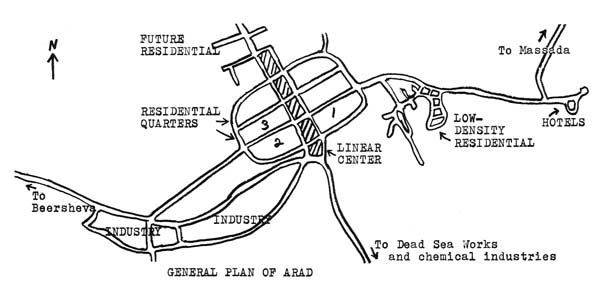

ARAD – a tight-knit new town turned inward from the desert wind and heat to face a linear city center.

Map shows Arad almost alone in Negev Desert. The hotel resort area is on a high point overlooking the Dead Sea, and near the road to the first-century mountaintop ruins at Massada.

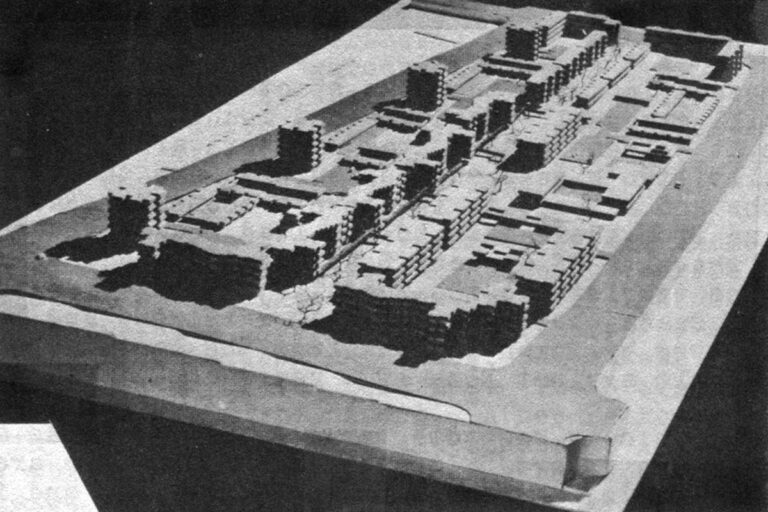

(below) An architect’s model and an artist’s view of Arad’s third residential quarter (#3 on map below).

Note: the well-sheltered main pedestrian “street” that runs down the middle of the quarter to the adjoining section of the linear town center. This quarter is now under construction.

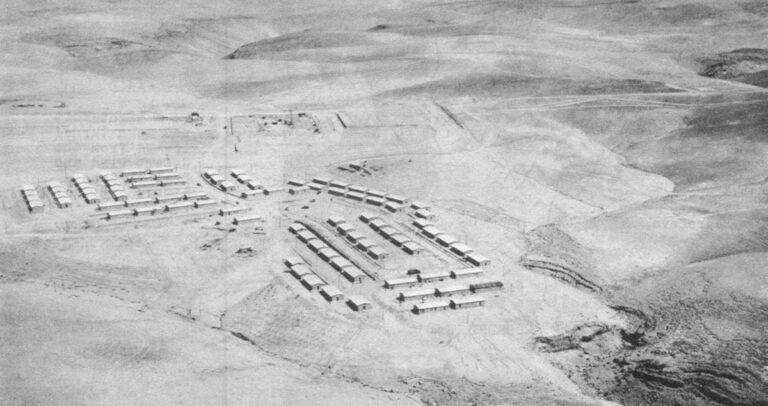

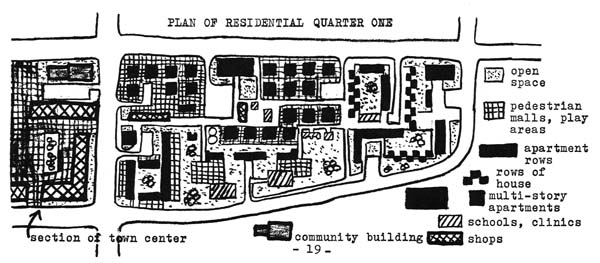

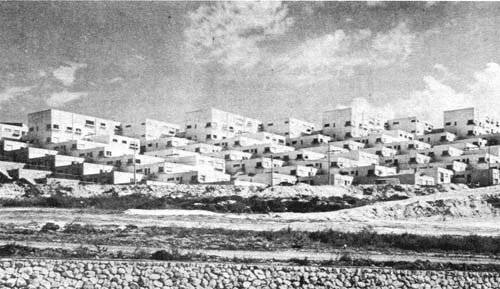

First residential quarter of Arad (#1 in map at top)

…is shown in detailed plan

…in photo.

Note: stores, schools, clinics, open spaces, malls, pedestrian walks – all inside protective border of large apartment buildings. Auto access is limited to parking cul-de-sacs.

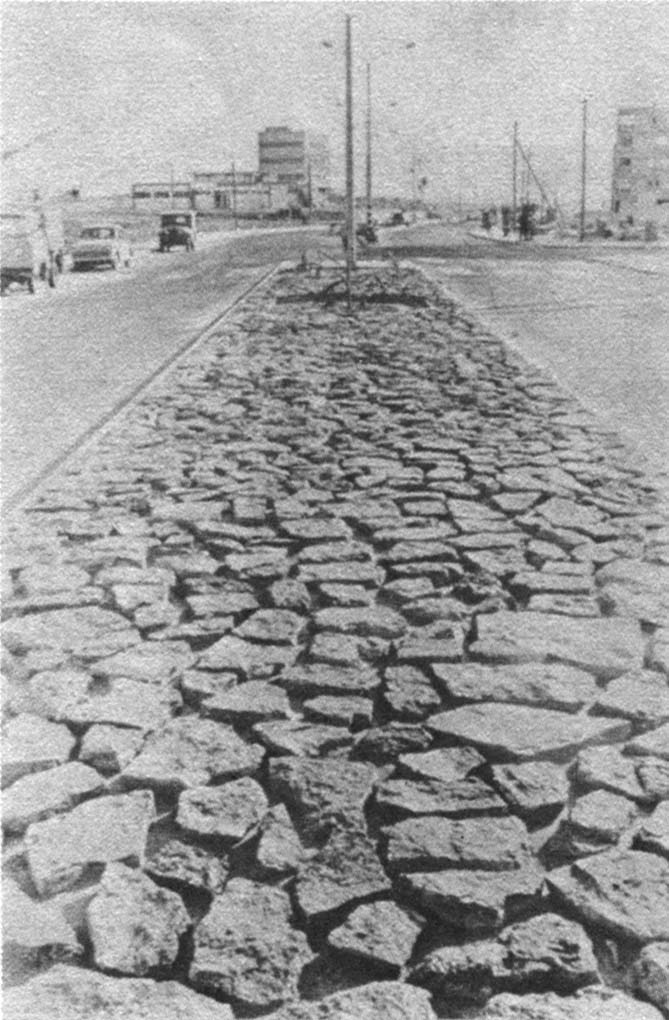

The planners responded with a plan for a densely concentrated community that encloses within a wall of protective buildings and low hills on its perimeter interior plazas, promenades and carefully tended greenery. Water is piped in from the west. A unique city “landscape” is being resourcefully crafted out of flagstone walks and malls, decorative stones rather than grass in the median strips of boulevards, and aggregate stone facing manufactured in the tan colors of the desert for the fronts of the buildings. Arad is becoming a picturesque man-made oasis in a region where the only other signs of life are the black tents of a few hardy Bedouins on the more gentle hills to the west and the fleeting glimpses of shy mountain goats on the bluffs of the eastern edge of the plateau.

Median strip in Arad: “landscaping” that does not need water

The majority (30,000) of Arad’s projected 50,000 residents are to live in a densely built-up central area placed in a slight depression in the plateau like a clenched fist held in a cupped hand. This rounded central area will contain six symmetrical residential quarters, three lined up on each side of a linear center of commercial and public facilities and gathering places that bisects the town from south to north. Taller apartment buildings on the periphery of the residential quarters, some of which almost touch each other, protect the interior spaces, the town center and the wide boulevards from excessive wind and sun. Pedestrian ways are shaded here and there by building overhangs. Apartments have private courtyards, patios or balconies enclosed by roofs and walls. Low, more open kinds of housing are built in the shadows of larger buildings.

Auto traffic is kept outside the residential quarters on large streets running between them and alongside the linear center. One can drive from one end of the central area to the other in a few minutes and on the main thoroughfare pass through all of Arad in five minutes. Yet it is also possible to drive into every part of each quarter on dead-end service lanes and park within 100 yards of any residence or store.

The “main streets” of the quarters and the town center are the pedestrian avenues. In each quarter, they pass by apartments, schools, nurseries, clinics, synagogues and small stores for daily needs before crossing a single auto street to reach the town center, which opens up into broader plazas inside groups of larger stores, banks, a post office, a cultural center, cinemas, the town administration and other facilities, many of which are already in place. Although each residential quarter will have its own name, unique “floor plan” and necessary daily services, they will tend to blend into one another, and the town center, to form a cohesive whole. Thus, the central area’s density serves both as protection from the desert’s less friendly elements, and also as a means to make what always will remain a fairly small city a nevertheless relatively urban place, more urban already, in fact, than several larger “first generation” Israeli new towns. The compactness of the center, and the staging of the construction of the linear commercial and governmental spine to coincide with the development of the adjacent residential quarters also makes these facilities more economical, even though their physical quality is a marked improvement over that of many other new towns in Israel.

“A certain density is needed to absorb initial costs of the infrastructure (public buildings and spaces, roads and utilities) and, later, to maintain it,” explained Shmuel Horwitz, a Ministry of Housing new town planner. Streets, walks and pipelines are relatively short in Arad, and yet sufficient to serve 50,000 people. In the United States, pointed out Horwitz, who studied urban planning there, suburban and even “new town” developments for similar size populations are spread out over so many hundreds of acres that very high infrastructure costs must be passed along to residents in high home prices and local taxes for maintenance, with the result that only the middle class can buy into them.

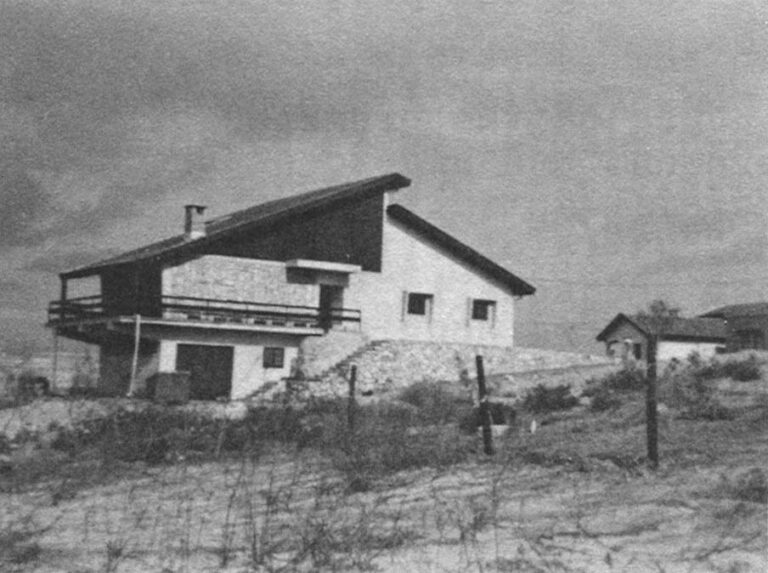

There also is a definite market in Israel for suburban-style living, and Arad’s design provides for that too. Outlying neighborhoods planned for a total of 20,000 people are to be nestled into protective hillsides surrounding the central area. One of these neighborhoods, with an open view of the center of town and the plateau beyond it, is already being filled with privately built, higher priced single-family homes in individualized styles. These areas are to have more complete subcenters of their own in the future.

Arad’s undeniable urbanity in so remote a location, its growing architectural and aesthetic appeal, and its adaptation to the surrounding desert all provide striking contrasts between it and a notable American new town project being built in a similarly isolated, rugged desert setting. The American development, Lake Havasu City, Arizona, is being promoted as a “prototype” for future new towns of its kind(See LD-3, Two New Town Mirages). It is being built by private contractors with a “master plan” and public facilities provided by its founder, Robert McCulloch, a Los Angeles real estate investor and manufacturer of chain saws, boat motors and small aircraft. McCulloch is moving his factories to the new town, which is located on the shore of man-made Lake Havasu on the Colorado River along the California-Arizona border in what also is otherwise empty desert far from any big city. Like Arad, Lake Havasu City is being built as a self-sufficient settlement on an economic foundation of specialized industry (in this case, McCulloch’s) and tourism (Lake Havasu is being used for water sports and a backdrop for the London Bridge, which was rebuilt there after being carted in pieces from England).

Despite these similarities, the two projects could not be more different in their respective methods of execution. Rather than being a closely planned experiment in land use, architectural design and social intercourse in a remote desert setting, Lake Havasu City is basically a real estate sales promotion with a layout no different than if it were being built in the San Fernando Valley outside Los Angeles. Although the temperature is hotter than in Arad, Lake Havasu City is growing as a loose connection of single-family homes, house trailers, small apartment buildings and cinder block stores scattered widely across the barren rock and dust; everything is exposed to the unrelenting sun. Nothing is located within safe or convenient walking distance of anything else, and there is no public transportation. Except for the focal point lakeside recreation areas, the project has no unity of design or overall physical sense of community. Except for its tourist hotels and well-watered golf courses, its landscape remains desolate and uninviting.

Lake Havasu City is not really making progress in coping with its environment or experimenting with any new forms of urban structure. Arad, on the other hand, located in almost exactly the same kind of setting (and without the advantage of a usable lake) is blossoming into a climatically sound, potentially attractive urban place.

Part of Arad’s promise is due to its social planning. Its first inhabitants were not the usual confused immigrant families talked into settling in an unknown new town project immediately upon arriving in Israel. Instead, they were all Israeli-born families or immigrants who had already been living in the country for some time. They were specially selected by the government for their needed special skills, economic stability and willingness to become pioneer settlers at Arad (in exchange for certain housing and tax subsidies). Among them were all of Arad’s government planners, who were required to live there.

As a result, the population of Arad during its formative years has been unusually young, adventuresome, highly skilled, and economically secure group of people, who soon created an enviable esprit de corps. Only now are some new immigrants and lower income families being placed among the oldtimers there. The town’s progress to date has shown that not only are many of its physical planning ideas probably suitable for duplication elsewhere, even where climate is not so singular a factor, but also that a more self-sufficient body of early settlers is important, especially in so difficult a location.

If, however, as could be argued, Arad’s unique location minimizes the widespread applicability of its planning concepts, there is also now underway another project, in a friendlier climate in the northern part of Israel, where these same concepts are being tested, some to even greater extremes. The site for this laboratory for Israel’s urban future is in an area that has often been important in the country’s past, the rocky gray and green hills of central Galilee. Through a riverless valley there, just south of the mountains that lead into Lebanon, travelers have passed for centuries on the road from the Mediterranean coast to the Sea of Galilee. Alongside that road, in an ideal bowl of low hills almost exactly halfway between Haifa on the coast and Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee, is where Karmiel, Israel’s newest new town, is being built.

It is to serve no special purpose, such as the development of a port as at Ashdod, or establishment of a vital desert outpost as at Arad. Karmiel is only supposed to become a new city where none was before, to support itself with whatever kind of industry it attracts, and, the planners hope, to evolve into the kind of attractive community that will lure Israelis away from the congested coastal area not far away. Without the special advantages of Ashdod’s port or Arad’s industry and tourism, these simple goals could be large orders.

Karmiel is not to be an urban marketing center for a large agricultural area, as most first generation new towns were built to be, primarily because most of the good farmland around Karmiel is owned by Arabs who trade in their own good-sized villages there. The Arabs of Galilee constitute the highest concentration of non-Jewish citizens anywhere within Israel’s pre-1967 borders. Karmiel will be, in fact, central Galilee’s first predominantly Jewish community. The government controls 60 percent of the land in the area, much of it being unplowable rocky terrain, and Karmiel’s site is the best situated parcel of that land on which to build a city. Its weather is relatively mild summer and winter. Rainfall is plentiful and there is sufficient underground spring water for a city’s needs. From almost every point on the site, there are pleasant views of surrounding hills and an expansive sky.

As at Arad, the planners designed every aspect of Karmiel in meticulous detail – not just the general land layout, road system and provisions for water, sewage and utilities (the basics of “master plans” for most American new town projects) – but also the three-dimensional architectural design of each residential area and its adjoining section of the linear town center. The development then was carefully staged so that adjoining or complementary residential areas, town center facilities, industrial plants, parks, roads and utilities could all be developed together and completed before the next group was begun. As a result, at any one time during its construction, the finished part of Karmiel is a cohesive whole, with all facilities needed by a town of its size at that moment, and with no large empty sites of “future” this or that.

Karmiel’s linear center is to bisect the entire community in a mile long arc to be built from the northeast corner near the bus station, industrial plants and entrance to the town from the main highway, to the southwest, where residential neighborhoods are to climb the low hills. Cutting across the community from the northwest to the southeast will be an irregular green band of park and open space, weaving in and around residential areas and opening into a large public square where it intersects with the linear town center. At that square will be built the town hall, a youth center, museum and other buildings, with a swimming pool (already built), sports stadium and other facilities just southeast of the square in a continuation of the park that would be directly connected with the rest of it by a broad passage under the public square.

Paths that take pedestrians past abundant greenery…

and around corners and down narrow stairs in Karmiel’s first residential area.

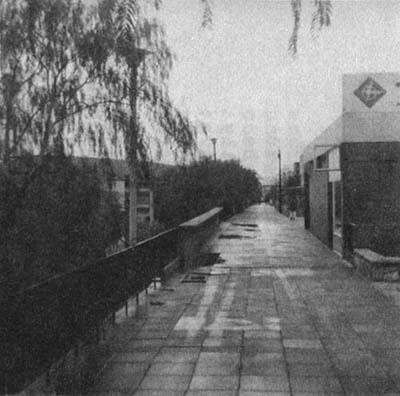

As in Arad, auto streets would be confined to outside and between residential areas, with the city’s principal boulevard running parallel to the town center. In Karmiel, this boulevard is an already begun divided highway on a ridge overlooking the town center, providing incoming motorists with an impressive view of the growing heart of the city, and residents on the malls and pedestrian ways of the center with a view of the bustle of traffic. This latter was done very purposefully.

Horwitz expressed the current feeling among some planners that residents want and enjoy the sight and sound of automobile traffic. This relieves the “overly serene” sterility of car-less places. Although people will see more auto traffic from pedestrian walks in Karmiel, they will be better protected from its danger than in earlier Israeli new towns by several pedestrian bridges over the main auto roads.

Karmiel’s first residential quarter and adjoining section of the linear town center are already completed in much the way they were envisioned in the original plans. The residential area is a long, narrow, intricately designed pattern of apartment buildings placed around groups of attached, single-family “carpet houses” with walled-in yards on the gentle slope of a hill. A main pedestrian street runs along the entire quarter parallel to the adjacent town center, with many smaller walks branching off it and running down the hill between buildings and rows of houses. Some buildings, open malls, playgrounds and planted areas have been dropped in irregularly so that most walks off the main one turn here and there or go up and down stairs in the seemingly random way that narrow streets form interesting mazes in older cities. In a relatively small space, a larger world of “streets” has been created for pedestrians in Karmiel, and been made interesting by the different kinds of buildings and facilities and already flourishing trees and plants everywhere. It is almost a microcosm of one of the attractive hillside neighborhoods of Haifa.

KARMIEL CITY PLAN

The project is to be built in the stages roughly corresponding to the numbers in the residential areas and accompanying sections of the linear town center, industrial areas and open spaces. Large public square of government buildings and cultural activities is to be built where the west-east band of parkland and north-south town center intersect.

Karmiel’s first residential areas and adjacent linear center in middle.

In order for this pedestrian network to mean anything to the people living along it, Horwitz pointed out, there must be reasons to travel it. In Karmiel, all the necessities of daily living are located somewhere or other along the pedestrian ways: schools, day nurseries, small shops, clinics, synagogue and playgrounds of the residential quarter, and the other stores, offices, cinema, community recreation and government offices of the town center a bit further along. There are benches along the walks and lights to keep them alive at night. They are not afterthoughts put in for a few nature-loving citizens as an out-of-the-way alternative to the auto roadways; they are the main streets, back alleys and garden paths of Karmiel, the future nerve system of the city.

About 5,000 people live in Karmiel today – half new immigrants and half Israeli born or immigrants who have been in the country at least five years. “We think a one-to-one ratio is best,” explained Mayor Baruch Venger. “We planned it so that newcomers and veterans (including the town’s planners) live together in the same buildings. The layout of the town also brings the different kinds of people together. In Karmiel, there are people from 20 different countries who grew up speaking 25 different languages.”

Instead of reserving the largest and best located homes for Israeli oldtimers while fitting immigrants into what is left over, Karmiel planners and officials, according to Venger, offer large homes to larger families and small ones to smaller families, regardless of their length of residence in Israel. Newcomers as well as other Israelis are eligible to buy new homes; yet they may occupy the same homes at low government-subsidized rentals if that is all they can afford. As a result, it is harder to pick out the new immigrants by the places in which they live in Karmiel. It is a less stratified community than are many other Israeli new towns built earlier.

The only American new town project presently committed to a similar mixing of widely divergent income groups in each building and neighborhood is the Cedar-Riverside project, being built on an urban renewal tract adjacent to the University of Minnesota campus in downtown Minneapolis (See LD-1, The Midwest: An Unlikely Laboratory for New Towns). It intends to place well-to-do families and those needing government housing subsidies in the same high-rise buildings, with a public housing building almost next door. It also intends to use lively pedestrian avenues and walks to further bring people together as they walk each day to school, work and stores. Its means of separating pedestrians and autos promises to be even more sophisticated than Karmiel’s: in some places cars are to be kept on streets and in parking lots several levels below elevated pedestrian areas. Unlike Karmiel, however, Cedar-Riverside, as an experiment, is not forced to sink or swim entirely on its own. It will benefit considerably from its university neighborhood location, proximity to Minneapolis’s commercial downtown and the unusual cultural activities existing, and to be preserved, in the old neighborhood it is replacing.

The government builds everything in Karmiel: homes, stores, offices, government buildings and, of course, the roads, recreation facilities and the rest of the town’s “infrastructure.” The city government is loaned money by the federal government with which to buy the schools and the city administrative buildings. All land remains under national government control. Overall, about half of the housing in Karmiel is sold to residents, and half is rented. There are several government subsidy plans to help young married couples, immigrants of all kinds and other resettling families to buy their homes. In addition, families moving to Karmiel are given tax reductions, and families with teenagers do not have to pay high school tuition there, as they must in most other places in the country. These subsidies, as well as Karmiel’s location, scenic setting and community plan, are expected to bring to it residents who might otherwise choose to live in Haifa or Tel Aviv.

“We also attract new people with our schools,” Venger said. Israel is not immune to the educational problems that many other countries are suffering these days. It often has particular difficulty maintaining good school programs in the new towns, with their variety of new immigrant children and classroom shortages. Usually, many teachers in new town schools commute long distances from bigger cities or are temporary teachers, usually immigrants themselves, who agreed to a short stint in a new town as part of their package immigration agreement with the government.

Venger said he made certain, however, to hire “a good manager and interested teachers. We expended great efforts to find good people,” he added, “because good schools are important to the kind of people we want living here. These are not bad children that we sometimes have, just many different ones. Educating them requires dedicated, good people.” To work in Karmiel, at good salaries, teachers must also live there, an unusual requirement. “We want our teachers to be part of the community and able to see their children after school hours, too,” Venger said. By living there, the teachers also increase the proportion of college educated professional people among the town’s residents.

Actually, Karmiel’s widespread reputation as a physically attractive, experimental community has brought to it more ” academic” people than were originally expected or than there are now professional jobs for. “Many of them have to work outside,” Venger said, “usually in Haifa. But that is not too far, really; most of them have cars and are used to commuting, especially newcomers from America. We are realizing that some commuting may always be necessary.”

The vast majority of Karmiel’s wage earners work right there in town, however, making airplane parts, shirts, dresses, cosmetics, shoes, a variety of specialized metal and plastic products, and the pre-cast wall sections for Karmiel’s buildings. Among the laborers and craftsmen working in these jobs are several members of Israel’s first urban kibbutz, a group of immigrants from the United States who formed Kibbutz Sha’an in Karmiel. Unlike members of rural agricultural kibbutzim, the families in the small Kibbutz Sha’an do not all live together. They are scattered in apartments throughout the town. They pool their earnings, however, and pay out to each family what it needs, proportionate to the family size. They also get together often for group meals and recreational and cultural activities. Although most of the men are college educated, they are working in factories or at individual crafts in Karmiel. Mayor Venger believes that Karmiel must be on the right track if it can attract this kind of new resident – people actively experimenting in new urban lifestyles.

“There is spirit here,” Venger said. “When a tree is planted, everyone knows about it and shares in it.” Such boasting may belie Venger’s role as a politician. Like all Israeli new town mayors, Venger was originally appointed to the job by the national Ministry of Housing, for whom he worked. More recently, he won re-relection when residents of Karmiel voted locally for the first time. (Such prompt granting of self-government is another Israeli new town innovation.)

“I guess they thought I was doing a good job,” he said, more with earned pride than vanity, as we talked in his temporary office in the town center, overlooking an attractive stone plaza surrounded by the town’s first stores and offices. He was, like many Israelis, matter-of-factly, and a bit immodestly, proud about his involvement in a pioneering experiment. Venger, Shmuel Horwitz of the town planning office in Tel Aviv and many other Ministry of Housing planners are not what one expects of “civil servants,” just as Karmiel is not what one expects of a government-built project. After years of frustration, evangelistic Israeli planners are proving that exacting planning and government control of such projects can produce worthy innovation, quite the opposite of what Americans have come to believe.

As in any true experiment, problems have arisen in Karmiel, though some of them stem more from national economic conditions than flaws in Karmiel’s own planning and execution. Israel’s economic slowdown of the mid-1960s and the expense of the 1967 war forced an almost complete standstill in construction at Karmiel from 1966 to 1968. The slowdown in the planners’ careful staging of the project prevented it from acquiring as soon as planned some of the urban services and attracting some of the merchants that were expected to help fill out its town center. Only recently was a cinema built, for instance. The lag in growth caused the government’s commerce ministry to channel fewer job opportunities to Karmiel, which, in turn, threatened to hold back further population growth once construction was resumed. Karmiel’s physical urbanity and attractiveness combined with the other inducements to keep people coming and the project going, although the town still faces a crucial period in the next few years as its planners and builders try to align properly again the growth of its various components.

Venger also sees the need to expand quickly the town’s human resources: recreation facilities, cultural services, variety of goods offered in its stores, social organizations, and the countless other aspects of an urban atmosphere by which one measures a community’s livability. “It’s not merely one problem,” he said, “but many little ones that can become one big one.”

There are nevertheless signs of the “spirit” that Venger spoke of so proudly. The part of the town center that has been finished already contains attractive landmarks – a large outdoor sculpture and a striking clock tower. Although the city administration occupies only temporary offices on the second floor there, everyone directing visitors proudly refers to it by the Hebrew phrase for city hall. In the residential areas, the buildings and planted areas are much better maintained than even those in many upper income apartment suburbs of Tel Aviv and Haifa.

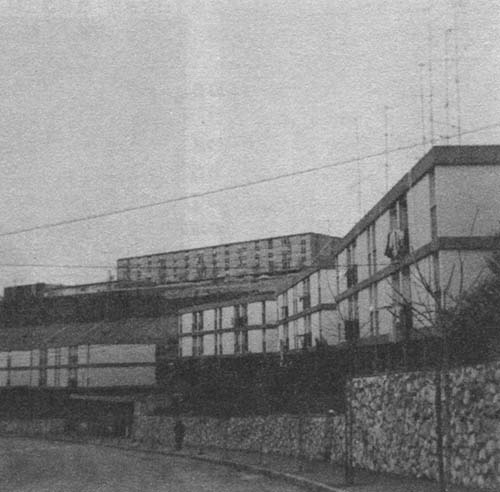

“Terrace houses” in Upper Nazareth – two views.

(Israeli gov’t. photos)

Many of the planning and architectural concepts being tested in Arad, Karmiel and, to a lesser extent, Ashdod already are spreading elsewhere in Israel. The “carpet” pattern of connected single-family houses with walled-in patios – and another version for steeper hills, “terrace houses,” in which the roof of one house serves as the patio for the home above it – have been built, among other places, in the older new town of Upper Nazareth, where they relieve the monotony of look-alike rectangular apartment buildings strung out on the hillsides.

The pedestrian pathway systems and small parks along them are showing up in the better planned suburbs outside Tel Aviv. Especially sophisticated pedestrian “street” systems are being developed and kept well separated from auto traffic in the expensive apartment developments rising on the hills of Jerusalem. These apartments are being designed and grouped together so as to preserve scenic views (the Dead Sea can be seen from some of the ridges), protect residents against Jerusalem’s sometimes harsh climate from the Wilderness of Judah desert, and fit in aesthetically with the surrounding landscape – just as has been done in Arad and Karmiel.

Some of the new design concepts are also being used in new homes built by the government for a community of Bedouins who had given up tents to live on the outskirts of Beersheva. Specially designed for the desert climate, these homes are divided into “guest” and “family” wings so the wife can enter and leave the house without going through the guest area, in conformance with Bedouin custom.

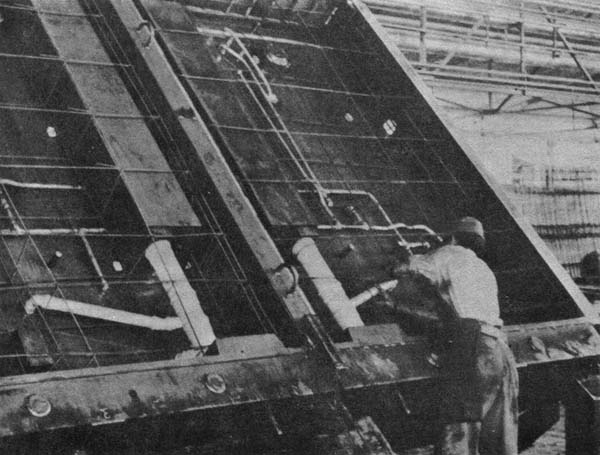

The Arad and Karmiel projects also pioneered new methods for on-site mass production manufacturing of building parts. A plant based on the French-developed “Ballancy” method is producing prefabricated building walls and load-bearing partitions for construction at Arad. Even pipes for plumbing are put into the interior walls in the plant before they are taken a short distance across the town and assembled into housing units. Polystyrene insulation is sprayed onto the inside of the exterior walls which are then covered on the outside with a decorative aggregate of beige stone. In Karmiel, a variation of the Danish “Modulbeton” method is used to produce both walls and floors for that new town’s buildings, leaving even less to be done on the building site itself. The attractive stone used for the facing of the buildings there is taken right from the ground on which Karmiel is being built. These methods have helped reduce some costs and construction time in new town development, while still providing many jobs in the pre-fabrication plants.

It is necessary to remember, however, what is not being done in the second generation new towns of Israel. In Karmiel, for instance, although the water supply and sewage pipe systems were carefully designed and staged with the rest of the town’s development, the method for disposing of the sewage is relatively unsophisticated – putting it into “oxidation” ponds to await natural chemical changes – which could cause future pollution problems if impurities make their way into the soil and water table.

Industrialized housing: an interior apartment wall being made, complete with built-in plumbing pipes and fixtures, in Arad factory (left), and pre-cast exterior wall being set in place on building site (top).

(Israeli gov’t. photos)

In all the new towns, overhead utility wires, individual television antennas and rooftop water heaters (which use energy from reflected sunlight to help heat the water, thus conserving electricity) mar the otherwise impressive progress that has been made in building design and landscaping. Another sight common to old and new towns is laundry and bedding hanging out windows, over railings or on clothes lines on the outside porch which every Israeli apartment has. Apparently laundry facilities have not been included in most apartment complexes. Attempts to correct what some consider the eyesore this causes include construction of a private outdoor space for each apartment that is hidden from public view by a decorative outdoor partition.

Nowhere, even in Karmiel where there is to be one parking space per family, has the likely eventuality of an Israeli motorcar explosion been planned for. And the absence of any rail mass transit means increasing pollution of the air with bus and auto fumes. Sophisticated sewage disposal plants, underground utilities, cable television, subways, even underground parking are all “luxuries” that present day Israel cannot afford, even for its showcase new towns. These heavy expenses are being borne in some projects in Europe and the United States, however, and freedom from them may help explain why Israeli new town builders have more leeway to experiment in other ways. Putting off those big expenditures, however, likely will result in serious future problems for Israel.

Industrialized housing: an interior apartment wall being made, complete with built-in plumbing pipes and fixtures, in Arad factory (left), and pre-cast exterior wall being set in place on building site (top).

(Israeli gov’t. photos)

It is also obvious that the recent strides made in new town building in Israel most benefit the newest immigrants (the Soviet Jews), and the select Israelis and more settled American and European immigrants that the government lures to the new towns with financial inducements. Tens of thousands of “Oriental” Jewish immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East, meanwhile, still can find no better homes than the worst little boxes in the near slums of the badly planned early new towns and the delapidated housing of formerly Arab ghettos. The country’s remaining Arabs, as a group, also are badly housed, despite a few efforts like the project for Bedouins outside Beersheva. In Jerusalem, the luxury of the reconstructed Jewish quarter within the walled old city and the high-rise developments on the surrounding hills will contrast sharply with the crowded, decrepit homes of impoverished Arabs in other nearby quarters of the old city.

In fairness, it must be noted that some Arab slums, such as those in the port area of Haifa, have been torn down (although sometimes for new housing for Jewish immigrants rather than the Arabs, who must then seek homes elsewhere on their own), and extensive work is being done to correct problems in the immigrant-filled older new towns. Overall, in fact, Israel has built a remarkable number of new homes, including many in the new towns, for its lower income families, a claim that few governments or new town community builders of other countries can make. Even the carefully selected populations of Arad and Karmiel are to be 50 percent new immigrants and lower income families. They are not “country club” new town suburbs like one finds in the United States, and somewhat in Europe, where most homes can be afforded only by the middle class.

Israel also is proving that innovation, imagination, excitement and even beauty in spots can be produced by government planning and building. Its financial commitment to housing construction and new town development is amazing when compared to its overall budget and the cost of defense. By contrast, the small amount spent by the United States government for similar programs is indeed paltry.

But the most remarkable aspect of Israel’s new town building program is its boldness in experimentation. Everything that they had heard of being tried elsewhere, as well as ideas of their own, has been attempted by the Israeli planners within the limits of their budget. This strategy has produced whopping blunders, which in turn made “new town” a phrase that still must earn more respect for many Israelis. But it has also produced remarkable progress in a little over two decades in an economically evolving nation.

This readiness to experiment, and risk money in the process, is the primary lesson that Israel’s new town program provides for the United States. Americans still are not ready to make enough of a commitment to so much innovation or such a high level of spending for improvement in the housing of their lower classes. They suffer instead the wastes of half-measures by the government in the housing field and the follies of real estate promoters doing business as usual under a “new town” sign that frequently may constitute false advertising. Israel gambles because it must, and it has something to show for it. When one surveys the suburban sack of Santa Clara County, California, the pockets of the Brownsville slum in New York City that look like they have been B-52 bombing targets, or the kind of house that $20,000, $30,000 or even $40,000 buys the average middle class family these days, can we not help but wonder that such dire necessity will not soon be facing the United States.

©1971 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, the Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.