Rather than the usual gaggle of tourists, the crowd moving up Michelangelo’s monumental steps to the top of Capitoline Hill in the heart of Rome on a recent wintry night was made up of several hundred ragged men, women and children representative of the estimated 60,000 residents of suburban shanty towns surrounding the Italian capital. This particular group of families had been moved by the government out of a squalid slum in Pietralata, on the eastern edge of Rome, to only slightly better “provisional” quarters in nearby army barracks originally built for Fascist troops before World War II. They had gone to Capitoline Hill to take their plea for better, permanent housing directly to Rome’s mayor and city council.

Just before midnight, as the council neared the end of debate on a long-stalled plan for coordinated development of Rome’s metropolitan area, about 100 of the protestors outside burst into the town hall and began shouting their complaints and demands at startled council members. The disturbance, which included some scuffling between the more unruly invaders and some city officials and policemen, lasted well into the morning. Mayor Clelio Darida stayed in his office trying to arrange by telephone for new housing for some of the families and for assurances from several private contractors that apartments they were building for sale to the city might be finished soon. By dawn, however, most of the families who had gone to Capitoline Hill were back in the same beds they had left the previous morning in the army barracks.

Little could be done immediately for these people because the shortage of housing for low-income families in Rome has reached critical proportions. Several hundred thousand Romans do not have permanent, legal homes of their own. In addition to those in shanty towns that resemble the better known favelas of South American cities, homeless families live in improvised dwellings under old Roman aqueducts and in other ancient ruins scattered throughout the city, in substandard illegal apartments put up by unscrupulous builders literally overnight without permits, and, as squatters, in half-finished buildings being constructed by the government for other families on official waiting lists or by private contractors for higher income tenants.

The housing problem has been attacked legislatively by both the government of metropolitan Rome (Commune di Roma) and the national government of Italy with a number of commendable laws and programs to build more public housing, curtail exploitive real estate speculation and control suburban growth. But, as is often the case in Italy today, many of these laws remain nothing more than so many worde on paper. Execution of their provisions has been thwarted by bureaucratic disorganization, budget problems, and a perplexing lack of strong will to do better.

Like cities in trouble everywhere, Rome is not suffering solely from a shortage of decent housing. Nowhere else in Europe are city streets so congested with traffic, or the air so fouled by exhaust fumes. The Tiber River is an ugly, unsanitary brown ooze, and the city’s streets, buildings and parks are all filthy; not surprisingly, there are periodic outbreaks of hepatitis and diphtheria. In addition to the shanty towns, Rome’s suburbs have sprouted a forest of uniformly unsightly, disorganized apartment buildings, many of which were shoddily built in blatant violation of building codes, official master plans, or the capacity of existing streets, sewers and water lines; overloaded sewers (even the absence of sewers in some areas) have further polluted the water table, and low water pressure has reduced “running” water to a trickle out of taps in homes of many sections of the city. A subway system begun three decades ago still has only one completed line seven miles long, and the government-owned bus system, which plies a surprisingly comprehensive and convenient route system with rather rundown equipment, is losing money badly. In fact, the Commune di Roma is now more than one billiondollars in debt all told. Although the “eternal city” is still, for tourists, an amazingly well preserved museum of the accomplishments of Roman civilization dating back to well before the birth of Christ, it is also, as the modern home of more than three million Italians, suffering from classic symptoms of the kind of cancerous illness that is eating away at many of the world’s cities today.

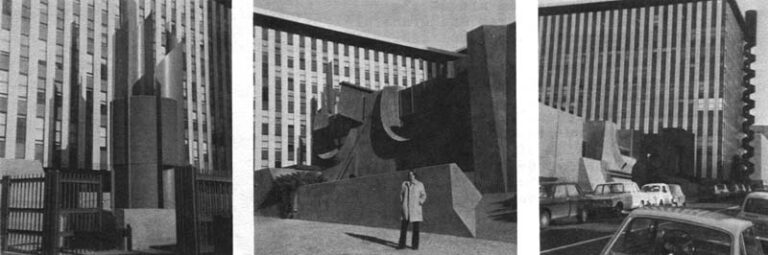

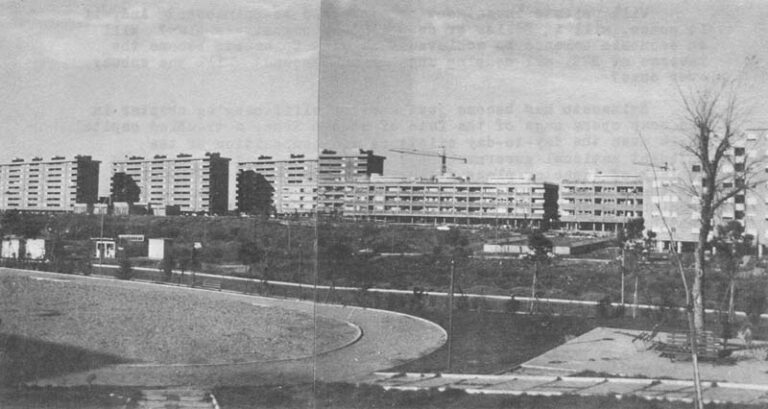

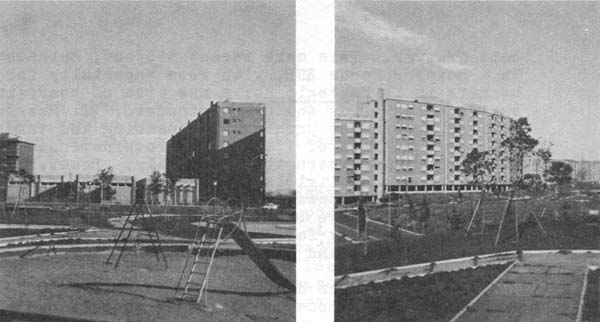

Typical scenes (left and on facing page) of inhuman scale, architectural monotony, neglected open space and traffic in Rome’s suburbs.

The families that confronted the mayor and city council in the town hall could not have chosen a more symbolic site for their protest than the Capitoline Hill. Rome has been governed from this spot (when it was not directly controlled by the Vatican) for perhaps 2500 years. The graceful town hall dates back to the Renaissance, when it was incorporated by Michelangelo into one of Rome’s most harmonious piazzas, the hilltop Campidoglio. In the time of the Caesars, the Imperial Roman Senate met where the town hall was later built on the ancient foundations, overlooking the broken ruins of the Imperial forums and, beyond them, the Colosseum. Ancient Rome itself once contained one million residents, and historians say its streets were badly bottlenecked then, too, by chariot traffic.

At that time, as John Gunther has pointed out in his book, Twelve Cities, “London and Paris were its colonies…and [today] Rome still ranks with them as a major capital.” But of the three, Rome is having by far the most difficult time coping with its modern population growth and attendant urban problems. From the Capitoline Hill one can see several signs of the city’s troubles: cars parked all over the Campidoglio’s 400-year-old patterned marble; monumental traffic jams in the Piazza Venezia below; the smelly smog in the air above, and, on that recent winter night, the milling throngs of the homeless besieging Rome’s city fathers.

Paris and London both began preparing long ago for their roles as modern urban centers by building subways, realigning streets, and developing planned, innovative new towns in their suburbs. Neither has become an urban utopia, by any means. Paris has several badly rundown suburbs, much smaller but nevertheless squalid shanty towns of North African and Portuguese immigrants, a shortage of adequate housing in all price ranges, and considerable air and water pollution; many critics also are appalled by the tasteless glass-and-steel towers that seem to be rising indiscriminately all over the city, even alongside the Seine. Greater London has, statistically, the world’s highest concentration of daily automobile traffic, even though it may move efficiently on its system of ring roads, and many of its suburban new towns, some of which date back to before World War II, are considered by many to be too stereotyped and regimented in design, only slightly more appealing than American Levittowns. Yet the accomplishments of the two cities are impressive compared to those of Rome: much more green space salvaged, more places for pedestrians to get away from cars, generally more attractive, livable neighborhoods in both central city and suburban areas, efficient subways and other public transportation, somewhat better housing for lower income families, and bold experiments in living patterns in more recent new town projects.

Rome’s “greatest distinction” meanwhile, “is, of course, its quality as a museum,” Gunther has noted. “But a metamorphosis is in process whereby the city is being forced to face the facts of contemporary urban life – the evolution is from museum to metropolis.”

Since Gunther wrote those words a very few years ago, fast-moving events have begun to distort that metamorphosis into a disastrous mutation that could badly ruin both the museum and the metropolis. The population of Rome has grown by 50 percent – one million people – in the last decade alone. Because very little has been done to fit this expanding population into the city properly, the pressure of their sheer numbers now threatens to despoil beyond salvation Rome’s environs, its last remaining livable neighborhoods, and its historic city center.

Rome’s dilemma is shared in varying degrees by all northern Italian cities, each of which has been inundated by a share of the six million Italians who have migrated to the north from the impoverished south and to the cities from the countryside since World War II. Some cities, notably Milan, with its urban renewal and transportation projects, have done more to adjust than have others. The national government also has made some progress in road building, revitalizing its railroads, and building a few impressive public housing projects, particularly in Milan and Genoa, where local governments have been willing and able to help. But, all in all, Italy is losing ground in the difficult struggle to build workable modern cities while also preserving the country’s considerable natural beauty and many ancient, medieval and Renaissance remains.

The average Italian is not quite so uncaring about all this as the popular happy-go-lucky stereotype of him might suggest. In 1969, twenty million workers closed the country down in a 24-hour general strike over the housing shortage issue alone. Many thousands of the shack dwellers in the Rome area have organized to protest their condition with demonstrations like the one on Capitoline Hill and the recent signing of 20,000 names to a petition of complaint. Each year, thousands of Italians contribute enough lire to support Italia Nostra, a large, quite active Italian counterpart of a combination of the Sierra Club, Urban Coalition and Nader’s Raiders in the United States.

Italia Nostra seeks primarily to prevent further destruction of Italy’s pine-forested countryside and historic town centers by land developers, industry and automobiles. Recently, for instance, Italia Nostrahas been pressing for government financial support for the careful renovation of the insides of historic downtown buildings in cities throughout Italy. The organization feels that using these buildings for modern offices or homes, before they decay from non-use or are torn down by developers, will revitalize inner cities as well as preserve historical sites. In pursuit of its aims, Italia Nostra has, of necessity, also become interested generally in community and regional planning. Its officials complain that their chief problem is the lack of similar concern on the part of important government officials and business leaders.

“We have no national objectives or plans, no government interest in preservation or orderly growth,” one Italia Nostra official told me. It is not quite true that plans are completely lacking. There are several progressive programs on paper, drawn up by one committee or commission or another, and some even adopted as law. But they have been almost completely ignored, even in cases where government officials have been charged by law to carry them out. This conspiracy of inaction – be it the result of the bribery of local zoning officials or building inspectors, a common complaint in Italy, or the lack of impetus and necessary public funds at higher levels – leaves the field clear to speculators and exploiters, who have proven to be as uncaring about the overall quality of life in Italy as are their counterparts elsewhere in the world.

As examples, Italia Nostra officials listed several of the current outrages their group is fighting: new villas going up among the ancient Roman ruins on what a recent law had designated as parkland alongside the historic Appian Way; a giant petro-chemical plant scheduled to be built on prime public seashore; the plans of movie producer Carlo Ponti to develop a “kind of Disneyland” where pine woods now stand; and the scores of non-conforming apartment buildings that have been put up helter-skelter in an area east of Rome where a government-planned, model “new town” was to go.

Thus, although many officials simply throw up their hands and blame the decreasing livability of Rome and its environs entirely on its continuing rapid increase in population, responsibility for the modern sack of Rome must also be shared by greedy developers and businessmen, along with their accomplices, unwitting and culpable, in local and national government. The story of how they have chewed up the Roman landscape and scuttled one reform plan after another during the last two decades provides a European sequel to such similar American sagas as the suburban exploitation of the once beautiful Santa Clara Valley south of San Francisco.

Rome’s present plight is all the more poignant because, until very recently, its comparatively small size for a major capital had offered an unusual opportunity to plan intelligently for its future. Unfortunately, however, its affairs were dominated by national figures who, from the first kings of the unified nation to Mussolini, and including the several popes of the time, were consistently more interested in building and preserving monuments than in such mundane matters as improving housing or other aspects of daily Roman community life. During this time were built such imposing modern edifices of state as the huge white stone “greco-italic” Vittoriano memorial to King Victor Emmanuel on the Piazza Venezia which Romans now refer to jokingly as “the wedding cake.” For his part, Mussolini was so disturbed by the sight of so many poor people living in shabby medieval houses inside his showplace capital that he simply tore those buildings down and sent their occupants scurrying to the outskirts of the city, thus helping to give birth to the first shanty towns.

After the end of World War II, the big Italian migration to the cities began, and the housing shortage in Rome grew critical. Profiteering builders jumped into the void, bought vacant suburban land cheaply and built block after block of tightly packed, shoddily constructed apartments for sale and rental to desperate families. When the demand remained far in excess of the supply, prices and land values rose and speculators moved in to buy up large tracts of land and parcel it out to builders at big markups. This boom has continued off and on since 1950, and Rome is now ringed by a thick band of these quick profit apartment developments.

In 1970 alone, according to one recently published estimate, landowners and speculators were paid $45 million for suburban ground on which 25,000 more apartment units were to be built. Yet today, ironically, with the Italian economy suffering a severe recession, hundreds, perhaps thousands of these apartments are vacant, in spite of a continuing overall housing shortage. These apartments have not been sold because the inflated value of the round under them has pushed their selling prices to as high as $50,000 a unit for housing of a quality worth, at normal Italian prices, only about one-third that much.

These are the kind of apartments one sees in Fellini’s movies: high-rises with balconies and a few showy features that are outweighed by their monotonously repetitive facades, bad plumbing, cracking walls, and spare grounds, much of which is nothing more than bare dirt covered with trash. They were built without any aesthetic consideration, overall land-use planning or regard for necessary public facilities. Most are crowded along much too narrow, traffic-jammed streets in suburban areas where there had once been space and time to avoid perpetuating the disorganized traffic patterns of central Rome. The buildings were put so close together in some areas that it has been difficult to find room on which to build schools, much less provide playgrounds or parks, none of which the developers did anything about. Many of the buildings lack even the first-floor space for convenience stores that are such an important, and pleasant, part of life in most European neighborhoods.

All this housing, it should be remembered, was built legally, with government permission and licenses. In the many cases where municipal laws or master plans did not permit a particular type of building or any housing construction without necessary attendant facilities and amenities, exceptions were somehow made. Even in areas where the government itself had decided to buy up land and supervise orderly development of satellite “new towns” on various sites, builders have been able, in the meantime, to obtain permission to move in and put up more blocks of dormitory apartments.

Ask Italians about all this and they laugh; they can’t understand why you don’t understand what is going on. They talk about bribes, conflicts of interest and about one hand of the government not knowing what the other is doing. One experienced foreign observer of Italian urban planning has also noted that “every political party in Italy, in or out of the government, relies heavily for its finances on those who happen to own large chunks of real estate.” That powerful land-owning group includes the big corporate developers, the remaining rich, aristocratic “ruling” families of Italy, and the Vatican, which controls one of Italy’s biggest real estate development companies, the Societa Generale Immobiliare (which built the ultra-luxurious Watergate Apartments on the bank of the Potomac River in downtown Washington, D.C.). These interests are particularly powerful in the Rome area, where there is comparatively little industrial wealth to offset them.

Elsewhere in Rome’s suburbs are what Italian city planner Piero Moroni calls “strange spontaneous towns” of “outlaw” buildings ranging from the small crude shacks of the shanty towns to communities of large apartment houses, all built illegally. “They are almost impossible to control,” said Moroni, who has made several studies for the government of Rome’s chaotic suburbs and suggested strategies for changing them. He estimated that there are 50,000 illegal dwellings in Rome and its suburbs.

The shacks, of course, have been pieced together by their occupants wherever a little ground and sufficient materials can be found: alongside roads, in open fields, next to railroad tracks and, especially, on the unlandscaped land around big, new apartment buildings where plenty of leftover construction material is usually available. It matters little who owns the land or what the law says.

Even more startling, however, are the large apartment buildings, including one of six stories and 130 units, that have been constructed just as illegally. They are built secretly by outlaw contractors, often working only at night, wherever water and power lines can be tapped. Usually the builders are working with the permission of landowners who were unable to get the needed construction permits and exemptions from planning laws and building codes that the buildings would be violating.

Sometimes, however, they are squatting on land owned by the government or unknowing absentee landlords. The apartments are sold well below market prices, a bargain for the buyer until he tries to resell what he has no valid deed to, or finds the construction faulty or the utilities undependable.

Despite the flagrant illegality of these buildings and shacks, little can be done about them. Italian law forbids the eviction of anyone from his home, no matter what kind or where it is, unless another is found immediately. Some homeless families have taken advantage of the government’s dilemma by moving right into nearly finished apartment buildings being built for other legitimate tenants by the government or private builders; once ensconced, they cannot be dislodged until they can be housed elsewhere. During a brief government crackdown on squatters and residents of unsanitary shanty towns recently, some families were moved to army barracks, where they have been loudly unhappy. Elsewhere, families resisting similar transplantation have fought pitched battles with police.

Except for the shanty towns, much of Rome’s illegal housing is not too different in quality or affect on the suburban landscape than the rows of “legal” apartments around it. They simply merge together into one aimless hodgepodge encircling Rome, all equally without the possibility of ever becoming attractive communities.

In 1962, a new master plan for metropolitan Rome was adopted to ease center city congestion and develop better suburbs. This plan, hailed on its announcement as a model worthy of study throughout Europe, provided for, among other things, the development of several satellite new towns around Rome. The first and most important of these was to be built just east of Rome, halfway between the center of the city and its outer ring freeway, the Grande Raccordo Anulare. This new town, planned for 500,000 residents, was intended not only to provide better new housing in a complete community of schools, parks, stores and well-planned transportation, but also to attract government and corporate offices away from downtown Rome. Yet the new town would be close enough to the center city to benefit from its proximity and, in turn, keep it from losing all life but that of tourism. The autostrada, or freeway, from Florence, which now ends just north of Rome, was to be extended to bypass central Rome and run instead through the new town before feeding into another freeway to the south.

Although this plan was adopted as law after long study by Italy’s most respected town planners, nothing has been done in the nine years since to carry it out. Neither the local nor national governments has come up with the money needed to buy the site, which was still largely undeveloped a decade ago. Nor has much been done to enforce the plan’s legal status by preventing nonconforming development on the site in the meantime. Land speculators have bought large parcels and contractors, with and without government permits, have been building block after block of apartments there. Shack dwellers and squatters soon followed, so that, today, one of Rome’s largest concentrations of illegal housing and shanty towns stands at Pietralata, which was to have been the specially designed central core of the planned new town. Any sudden decision now to go forward with the plan would require rehousing elsewhere tens of thousands of families and paying much higher prices for the land and existing buildings on it. Piero Moroni, who had worked on the original plan, told me that it “is all in the past now…. I’m doing other things today.”

Actually, realization of Rome’s new town plans should have been considerably aided by another 1962 law designed to reduce land speculation and produce more balanced suburban communities. Undeveloped urban land, including that which had not yet been built on around Rome, could be expropriated by the government at low agricultural land prices. New housing could be built on it only after the responsible local government provided necessary utilities, schools, transportation, church sites and other facilities. But the Commune di Roma has been unable to pay for any of this.

The Italian government also was required by other mid-1960s legislation to finance construction of 20 million new rooms of housing in a ten-year building program. Even though the money for this project has been collected regularly since from every Italian worker in a payroll tax, not even half that goal is likely to be reached on schedule. The program has been held up by bureaucratic delays in processing individual construction projects as well as by the inability of many local governments, like Rome, to provide community facilities for the projects. At the moment, the national government’s share of the total annual investment in new housing in Italy is only one-third of the 25 percent share required by law.

Much of the public housing built around Rome by government supported corporations is little different than that put up hastily by private developers. Although interior features have improved considerably, their facades and arrangement on the land are depressingly monotonous. Public gathering places, greenery, playgrounds and other facilities are skimpy or nonexistant. Because the government seeks the cheapest sites, more recent projects have gone up in isolated locations far from Rome itself, where only residents with cars or those with the patience to wait for and ride on buses for hours can get to stores and other services. In a particularly large public housing development at San Basilio, near an interchange on the Grande Raccordo Anulare northeast of Rome, residents have staged violent riots to call attention to the lack of facilities there. When such inevitable public uproars occur, the Commune di Roma and the national government merely continue to point to each other for leadership and more money.

A similar lack of fixed responsibility has undermined efforts to protect the remains of the ancient Appian Way south of Rome. This celebrated road into the countryside was began by the consul Appias Claudius in 312 B.C. and was eventually built up with Imperial Roman villas, tombs and monuments, large remains of which still stand today. Until recently, however, it was largely ignored by the government. Delivery trucks race over its 2,000-year-old paving stones, and an increasingly number of wealthy Roman residents, including movie star Gina Lollabrigida and exiled King Constantine of Greece, have built modern villas among the antiquities along the road. A law was finally passed a few years ago to make six miles of the Appian Way and much of the low, dark green hills dotted with gray stone remains on either side of it into a 6,250-acre park. Once again, however, little more has been done because the national and Roman governments have each insisted that the other produce the estimated $40 million needed to buy the land and develop the park. Meanwhile, developers have continued to build more villas and even some apartment houses on land designated for the park, although a few of these unfinished buildings were recently ordered demolished by angry Roman officials.

Some considerable success has been achieved, on the other hand, in preserving Roman ruins and renovating medieval and Renaissance buildings for modern use inside central Rome. Well-enforced laws prohibit destruction or exterior modification of these buildings. But they may be completely rehabilitated inside and added to at the top for a story or two, provided the addition matches the older facade. Italia Nostra, which has encouraged and raised money for this work (and for excavation and preservatior of underground ruins frequently uncovered daring renovation) believes it is best for these buildings to remain “alive” with the bustle of people. Because of the high cost, however, only business firms and upper income families can afford to stay in renovated buildings; thus, this program, in effect, pushes more lower income Romans out to the suburbs.

To some extent, however, the expensive renovation and preservation of buildings and monuments in central Rome is offset by the damage done to them daily by the city’s unbelievably dense auto traffic. Exhaust fumes blacken and erode building facades and statuary. Parked cars turn Rome’s most picturesque piazzas into crowded parking lots. Other cars, parked up on sidewalks and driven through pedestrians on narrow side streets have spoiled walking in a downtown area built on an almost ideal pedestrian scale.

On and off during the past decade, there have been several attempts to ban cars from various sections of central Rome, particularly during the peak summer tourist season. But each effort, like Julius Caesar’s ban on chariot traffic in the vicinity of the forums in 51 B.C.,has been short lived. The anger of drivers caught in even worse traffic jams than usual in the downtown areas left open to cars and the apprehension of shopkeepers that they were losing customers who could not drive to their stores were too much for officials to ignore.

The most recent experiment, however, has been better received than most. During the Christmas holiday period, the many colorful shopping streets and nearby piazzas from the Via del Corso to the Spanish Steps were closed to traffic. The resulting pedestrian malls, decorated with holiday lights, glitter, streamers, and huge paper balls, attracted crowds that packed the streets solidly, even on Sundays when the stores were closed. Merchants changed their elaborate window displays at least weekly to present constantly changing montages of merchandise to the throngs of windowshoppers.

In addition, and perhaps most important, all fares were abolished on the city’s bases for nine days to encourage residents to leave their cars home while shopping or going to and from work. The patronage of the buses increased by 50 percent, according to government estimates, and 11 percent of 14,000 passengers filling out questionnaires reported that, although they normally drive their cars in town, they had left them home to ride the buses free. As a result, city officials are now considering a plan to abolish bus fares permanently during the morning and evening rush hours, and to close a much larger part of the downtown area to auto traffic. The area proposed, from the Piazza del Populo on the north to the Colosseum on the south and from the Vatican on the east to the Porta Pia on the west, encompasses Rome’s most celebrated piazzas and historic buildings and monuments; all told, more than half of the area inside the ancient Aurelian wall built between 271-78 which still surrounds the center of the city today.

City officials are worried, however, about the cost of this plan. The nine-day free bus experiment at Christmas time deprived the government-owned bus system, which was already deeply in debt, of half a million dollars in lost fares. Some critics are concerned about turning to Rome’s buses at all as a solution to transportation or pollution problems. In a recent front page editorial, Il Messaggero, Rome’s leading newspaper, called on the judiciary to assume control of the municipal bus line and take steps to modernize it. The newspaper complained that the “obsolete, slow, uncomfortable” buses now in use discourage paying patronage and contribute more than their share to air pollution from exhaust fumes.

The obvious alternative is a subway, the mode of public transportation that has been the backbone of large European cities, including London, Paris, Rotterdam and Stockholm. A subway for Rome was begun 33 years ago, in plenty of time, it would seem, to be of important use today. Mussolini began construction of the subway in 1939 not as daily transportation for the majority of Rome’s citizens, but rather as a shuttle for visitors from the train station downtown past the Colosseum and other tourist attractions south to the site of a world’s fair that was to have been staged in 1942. World War II interrupted both projects, and that single subway line was not completed until 1955. A second line to run north from downtown, intended for use during the 1960 Olympics, is still years away from completion. A third line has only just been started.

Progress on the subway, a subject of much black humor in Rome, has been slowed by the usual money shortages and planning snafus, in addition to unexpected problems in avoiding damage to Rome’s archaeological treasures. On more than one occasion, the tunneling has ran directly into well-known underground ruins, which have had to be completely excavated and removed with great care before any other work could continue. At one point, subway workers broke a sewage line near the Villa Borghese gardens which began spilling into a large, empty underground lake next to a section of the 1700-year-old Aurelian Wall. The sewage flowing into the lake bed threatened to erode more ground and collapse part of the wall, so it was necessary to quickly gather up all the concrete available in Rome to fill the cavity while the leak was being fixed – another delay and another unexpected cost.

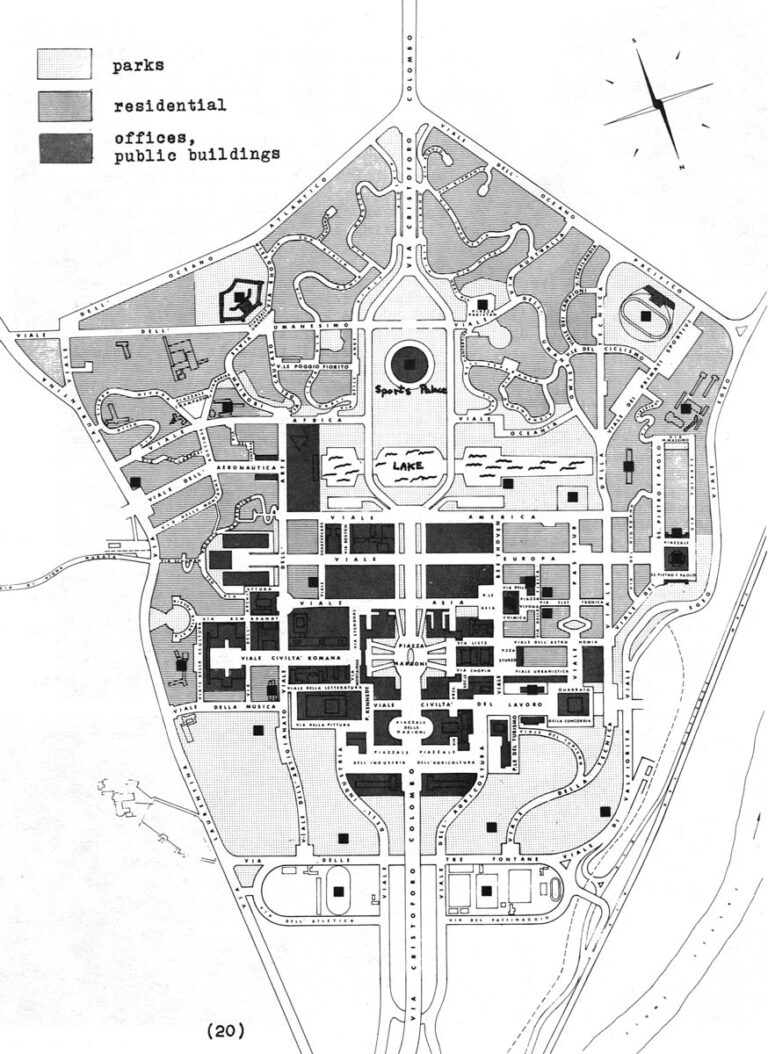

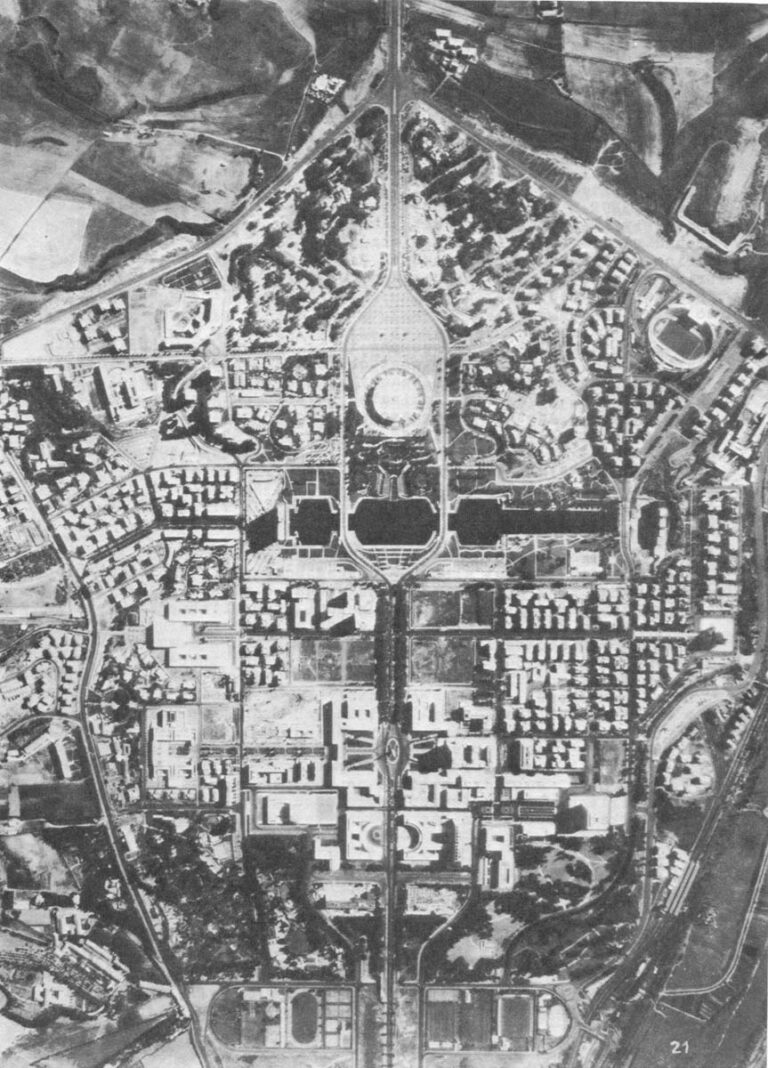

The existing subway line does, however, connect downtown Rome with one urban project with which Italy can be justifiably pleased: the new town of EUR just south of Rome. This politically and economically independent community of houses, apartments, government and corporate offices, and expansive parks is located on a symmetrical, hexagonal shaped site just five miles (and ten minutes on the subway) from the center of Rome. It is one of the most intelligently planned, aesthetically pleasing and financially successful urban development projects to be carried out in Europe during the time of its conception and principal development, from 1951 to the mid-1960’s. In contrast to the unappealing concentrations of apartments on the denuded landscape along the road south from downtown Rome to EUR, the new town appears as a seeming mirage of greenery and attractive urban architecture, rightfully entitled to an Italian legislator’s description of it as “the miracle at Rome’s door.”

EUR has gained little international recognition, perhaps because it, too, was originally one of Mussolini’s tastelessly grand showpiece schemes. It actually was conceived in 1937 as the site for the 1942 world’s fair that was never held (and for which the subway also was begun). “EUR” is an acronym from Ente Autonomo Esposizione Universale di Roma, roughly, the Indepenent Authority for the World Exposition of Rome. A national government commission was to carry out development there of imposing exhibition and meeting halls, sports arenas and stadiums, a huge permanent amusement area, dramatic piazzas, grand boulevards lined with trees, sprawling parks and formal gardens with picturesque promenades, fountains and a large man-made lake. After the fair ended, its principal facilities were to remain as a permanent exhibition and convention center, possibly to be joined by government offices moved from cramped quarters downtown.

Before the war intervened, the highway from Rome was completed, EUR’s boulevards and gardens were laid out, many trees planted, excavation for the lake begun, and an ancient obelisk to be the centerpiece of its central piazza was carted out from Rome. Several of the exposition “palaces” also were started, and some were finished. They were massive, boxy monoliths made of famous Carrara marble – throwbacks to the showy public palaces of Imperial Rome. The war interrupted all this work and brought with it aimless destruction of much of what had been finished at EUR at the hands of first Fascist and then Allied troops who encamped there.

By the end of the 1940s, the new Italian government recognized in what remained of EUR (which looked to Italy’s president at the time “like some ancient city fallen into ruin”) a unique opportunity to build a new subcenter for the Rome area that could also become a showcase of Italian architecture and urban design. The government realized, however, that such an ambitious venture at that time required considerable financial backing and some assurance of economic success. For help in obtaining both, they reached back to the best of Mussolini’s plans and applied them more practically. EUR, they reasoned, could be marketed as an international trade center with exceptional exhibition and meeting facilities and ideal sites for corporate headquarters and government offices, as well as homes for their executives. As events later proved, they calculated well. In time, a combination of the increasing cost of locating large business offices in other well-placed European and Italian cities, the wave of anti-Americanism that spread through France under DeGaulle, EUR’s strong government backing (an ironic exception to the rule in Italy), its attractive plan and promising layout, and a variety of financial incentives offered by the Italian government were to eventually attract to EUR more than enough interest and business to make the project self-supporting.

At the beginning, in 1951, when the national government set up a new commission, completely independent of the surrounding Commune di Roma, to redevelop and administer EUR, it loaned the project sufficient money to begin repairing and rebuilding existing public buildings and to continue development of roads, piazzas, utilities, parks and the lake. The Italian government contributed further by building several government offices there, including headquarters or principal branches of the Ministries of Finance, Defense, Merchant Marine, Foreign Commerce, Public Sanitation and Postal Service. EUR was then to finance further development, and pay off the government loan, from the proceeds of sale of land for private office and residential development, along with the rental of the public halls and buildings, which it would own.

An Armed Forces Museum, art collections and the national archives were moved into some of the buildings originally designated for exhibition use during the 1942 fair. An Olympic natatorium, outdoor stadium and huge domed sports arena – a focal point of the new town located on a hill overlooking the lake and a large public garden – were soon completed. A hospital was begun, along with several public clinics. Nurseries, elementary and secondary schools, a technical institute and the equivalent of a junior college all were constructed. What was destined to become another EUR landmark, the cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul, with a majestic, modern reflection of the cupola of Saint Peter’s in the Vatican, also was finished.

Swiss investors were successfully induced to take over operation of the international trade center, for which an unusually impressive (if overly grandiose) group of convention and exhibition halls were available. Then, one by one, along the broad avenues and piazzas and overlooking the parkland that was spreading out to every corner of EUR, international and Italian corporations began building showplace office buildings: ESSO, Mobil Oil, Procter and Gamble, Alitalia airline, the Vatican’s Societa Generale Immobiliare, and the Instituto Mobiliare Italiano (another large Italian investment banker and developer), among others. When NATO’s headquarters were booted out of France, it also moved some of its facilities to EUR.

The strikingly pleasing architecture of many of these buildings has combined with EUR’s growing green beauty to make the new town’s physical attractiveness its chief asset. There is in EUR none of the unrelenting sameness or cheap vulgarity of high-rises in so many downtown urban renewal areas or satellite new towns in both the United States and Europe. There instead are daring architectural sculptures and graceful examples of more traditional design, any one of which would stand up well alongside the best of midtown Manhattan. The chief difference between EUR and Manhattan, however, is that in EUR these buildings can be seen. There are picturesque vistas from parks that make up one-fifth of EUR’s land area. It is a visually open place; in addition to the parks and piazzas, there are lower buildings grouped around the most striking taller ones. Utility lines are all underground. It is clear that there has been strong central control of planning and design in EUR.

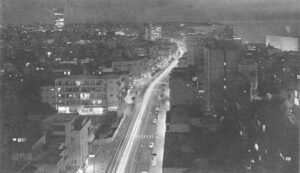

The visual grandeur of EUR

A large office building in park setting at one end of the lake, with apartment towers in background.

The dome of Saints Peter and Paul.

The dome of Saints Peter and Paul.

This attractiveness carries over into EUR’s residential neighborhoods, where tall apartment buildings set inside private parks have been spotted among acres of single-family homes on large, flowering lots. The convenience stores missing in too many of Rome’s suburbs can be found on the ground floors of office and apartment buildings. Stores are also grouped around EUR’s subway station, the end of the line from downtown Rome. The variety of functions that make up urban living are all there in EUR, including five hotels.

Nevertheless, there are many Romans who agree with Gene Fleming, managing editor of the English language Daily American of Rome, that EUR “is not Rome. Because I want to live in Rome, I would never live there.”

The wife of an Italian painter who lives in the middle of the noise, polluted air and snarled traffic of downtown Rome complained that EUR has no life after office hours. “Nobody is out on the streets after 8 p.m. there,” she said.

In fact, much of EUR is similarly still and empty of street life at midday if one wanders away from the offices in its center. Its residential neighborhoods are strictly suburban places, in the fullest American sense of the term. Ornate fences with locked gates surround grounds of most houses and apartment buildings. Automobiles are relied on for any trip longer than that to the shop downstairs. Most recreation facilities are in private clubs. The community contains just one class of people, upper income. Many of them are Americans or other resident foreign families of executives working there.

All together, EUR has only 15,000 residents now, and will never have more than 20,000. This is a relatively small population for an 1100-acre area cut off so well from its surroundings by an outer greenbelt and road system. Thus, EUR cannot serve as a model for the development of new towns for all income groups or of the population densities needed for the daily vitality and economic success of any community without so specialized an economic base or class of residents.

Despite its relatively efficient and usually scenic street pattern, EUR has fared no better than other projects begun in the early 1950s in coping with automobiles. A dearth of underground parking has left its piazzas as crowded with parked cars during working hours as those of Rome. The lack of pedestrian bridges and other sophisticated means of separating pedestrians from cars leaves only the paths through the parks as safe places to walk.

But there are still lessons to be learned from EUR by both Italians and Americans, the most obvious of which is the integrity of its architecture and the beauty of its landscape, proof that a quickly built, government dominated development does not have to be ugly or dull. Another Roman artist, Paolo Buggiani, who has chased the vanishing green countryside outside Rome to an old mill he has renovated to be his home north of the city, values EUR for its pretty face. “I like walking through its parks,” he said, “especially when they are not so filled with people as everything in Rome is.” He does not live in EUR, however, because he finds it much too expensive.

The strong, free hand that the commission running EUR has had in its development also has worked out well. The commission accomplished most of its goals and produced almost exactly the kind of community it sought, an unusual accomplishment indeed in a field where deadly compromise, especially in government initiated and controlled projects, is so often the rule. As EUR’s government today (it is not elected, but there seems to be no outcry from within for democratic rule), it is still a rare financial success. The approximately forty billion lire that it has spent on building and maintaining EUR’s public buildings, grounds, utilities and local services during the past two decades has been more than recovered through its land sales and continuing commissions and rental fees of its public facilities. Much more of a government subsidy would be needed, of course, to duplicate this experience with a denser, more economically mixed community, but a workable mechanism has nevertheless evolved at EUR.

EUR’s example has meant little to the development of the rest of the area around Rome, however. As has been discussed, nothing has come of plans by the Commune di Roma to build similar new towns. One veteran Italian newsman told me that “the only reason EUR worked out so well is that the city government of Rome couldn’t touch it.”

As unfortunate evidence to back up his judgment, he pointed to a satellite project of quite another kind south of EUR on the same main highway, just beyond its intersection with the outer belt freeway. This more recent project, Spinaceto, was intended to be a heterogeneous EUR, with room especially for the thousands of workers in il Mezzogiorno, a new area of heavy industry that begins a few miles south of Spinaceto. Il Mezzogiorno is an Italian government program of financing and tax subsidies to attract factories of Italian and international firms to the impoverished southern third of Italy. However, the northern boundary of the eligible area was drawn only about a dozen miles south of Rome. Consequently, most businesses taking advantage of the program have built factories right up against that boundary, not very far, in some cases, from their headquarters office buildings and executives’ homes in EUR.

Spinaceto was designed as a community for 45,000 people, one-sixth public housing residents and the rest a cross-section of higher economic strata, by a planning team headed by Piero Moroni. It was to be unlike the dreary suburban Rome apartment rows and public housing projects to which the factory workers would otherwise be restricted by market conditions. In Spinaceto, they were to live with other income groups in a complete community of apartments and houses, schools, churches, recreation and social facilities, underground parking, a station on an extension of the subway line from EUR and other features. Along the winding main boulevard down the middle of Spinaceto would be a linear “downtown” of stores, offices and government services, within easy reach by foot or car of almost every corner of the community. Everything would be carefully planned beforehand and put in its proper place.

Once again, however, it has proven almost impossible to transform a promising plan into reality. No strong, well-financed special authority has been set up to develop Spinaceto, as was done for EUR. The various government agencies with a hand in it have had little trouble arranging for the 250 acres of public housing being built immediately for 7500 people, but they have so far attracted no private capital or higher income residents. Moroni’s team, which drew up the land-use plans, did not also design the buildings, and they have turned out to be of the usual Roman public housing-modern style, although they have been grouped around unusually spacious and well-equipped playgrounds and open spaces, in which spindly saplings and sparse grass are now struggling to grow. A few sheds are serving as rather limited shops in the middle of a muddy field where the extensive commercial center was supposed to have been begun by now.

Will private investment be attracted to Spinaceto? And, if it comes, will it follow or despoil the community’s plan? Will an economic balance be achieved – or will Spinaceto become the reverse of EUR, all housing and all low income? Will the subway ever come?

Spinaceto has become just another cliff-hanging chapter in the soap opera saga of the fate of modern Rome, a troubled capital where even the day-to-day existence and composition of the resident national government has become problematic. There is no lack of ideas or plans for dealing with the city’s problems. But there clearly appears to be an absence of the will to carry them out, even as the modern sack of Rome, by its own citizens, continues.

Received in New York on March 27, 1972

©1972 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, the Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.