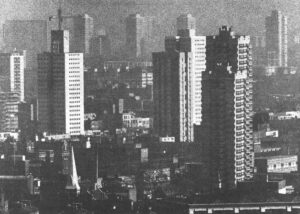

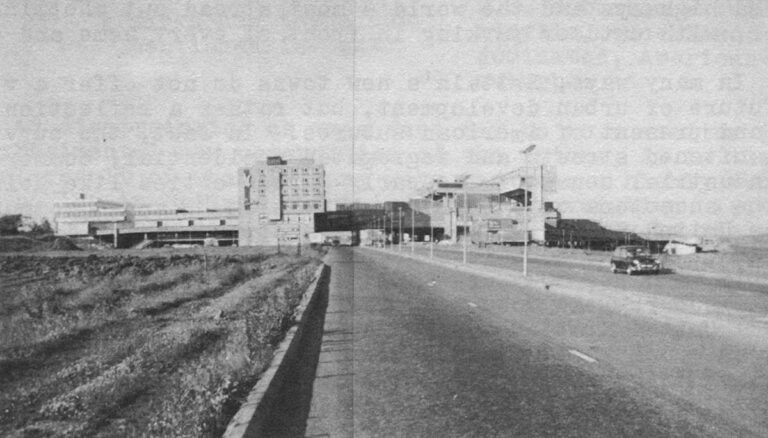

Straddling a divided four-lane highway on a windy hilltop northeast of Glasgow is a chaotic architectural montage of interconnected buildings and passages of various sizes, shapes and colors that has become internationally famous: the all-in-one city center of the new town of Cumbernauld. The irregular mass of stores, offices, apartments, a hotel and a church seems to be constantly in motion; as you approach, it takes on a different shape with every change in angle. It was meant to be the pulsating heart of Cumbernauld.

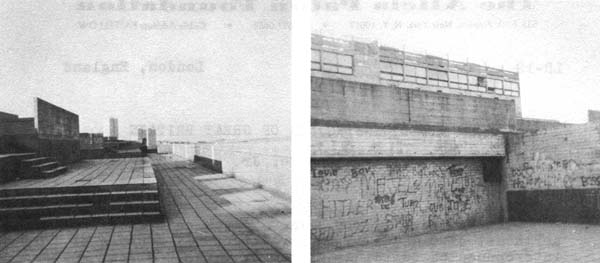

But as one nears the Cumbernauld center, its architecturally kinetic appearance gives way to the strange stillness of its empty approach roads and deserted pedestrian corridors, broken only by the rustle of wind-blown trash and the occasional shouts of marauding bands of children. Although the early evening sunshine is still bright, no stores or other facilities are open, except the hotel’s bar and dining room. Although the center is only a few years old, some shops have been vacated and boarded up. The center’s principal decoration is graffiti, scrawled bold and large everywhere, perhaps by the same vandals who have broken so many of the corridor fixtures and dented almost every non-concrete surface.

A tour of many of the 28 new towns of Great Britain produces more disappointments. Not far north of London, the old English village atmosphere of the shopping “High” and central green of Welwyn Garden City, a 1920s forerunner of modern new towns, has been overwhelmed by the automobile traffic of the 1970s. Further north, Stevenage, one of the first post-World War II English new towns, now seems too much like a giant shopping center and parking lot, American suburban-style, surrounded by a loose collection of lifeless residential neighborhoods. Still further north, fifty miles from London, at Milton Keynes, projected as a third generation “new city” for 250,000 or more people, the master plan, now being implemented, is a design for a miniature, planned Los Angeles of high-speed divided highways and the world’s most spread out shopping center, with outdoor parking in front of every home and store.

In many ways, Britain’s new towns do not offer a view into the future of urban development, but rather a reflection of the past and present of American suburbs. In fact, the curving, tree-softened streets and segregated residential, commercial and industrial zones of the early garden cities like Welwyn are the ancestors of suburban subdivision “planned communities” in the United States. Stevenage’s shopping center is the forerunner of the countless shopping malls that dot American suburbia, and its 30-year-old land use plan is much like that for the suburb-like Columbia, Maryland “new town”. As Britain and the United States have gradually traded places in recent years as model and imitator, the freeways, interchanges and sprawling drive-in shopping, service and cultural center planned for Milton Keynes are copies of the latest in California exurban development.

Most important of all, both British new towns and American suburbs are dependent on and dominated by the automobile. Nothing is so characteristic of the more recent British new town projects than ever larger and more complicated road systems and huge parking lots.

Traditionally in England “suburbs” have been tightly knit old towns that have greatly expanded along with nearby big cities. Somehow, many of them have retained much of their individual town identities even though politically, economically and practically they have been merged with their mother cities. There simply was not room in these peripheral communities for many more people by the end of World War II, however, so it is not surprising that the western world’s most ambitious government-supported new town building effort should produce – at the same time as the explosive growth of U.S. suburbia – rather sterile, one-class, automobile-dominated, American-style suburbs.

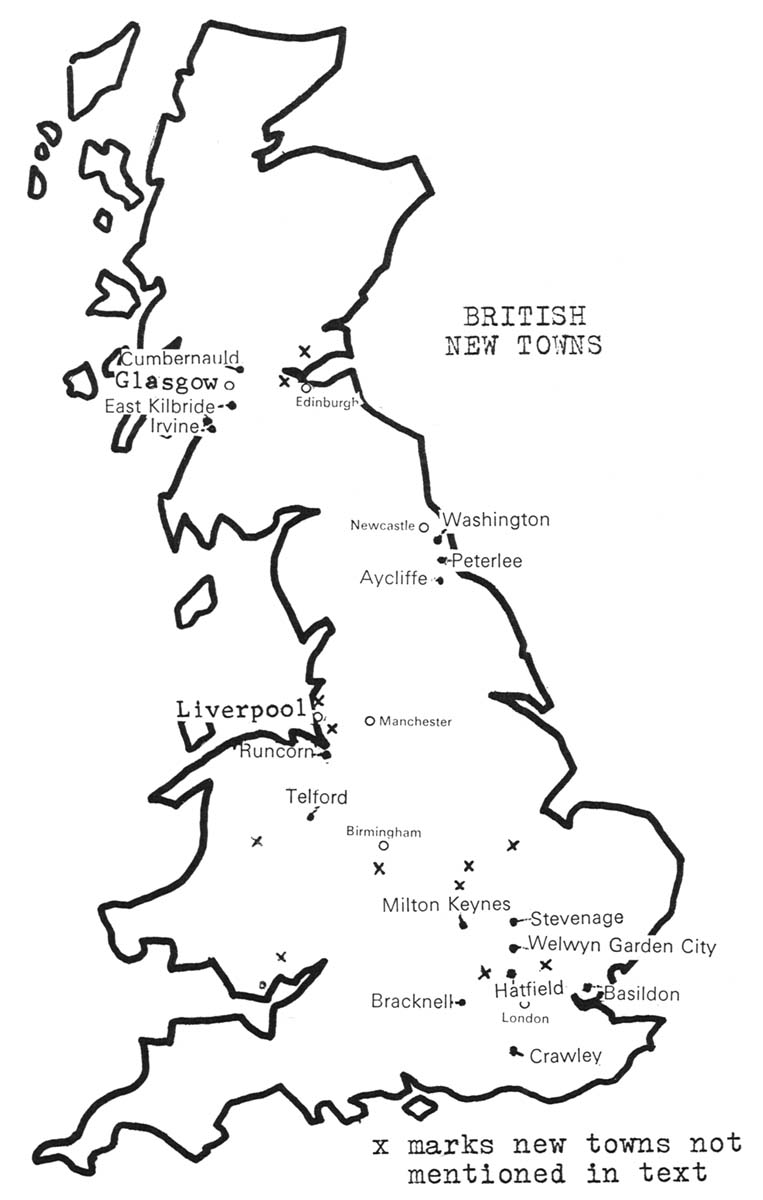

British New Towns

x marks new towns not mentioned in text.

As disappointing as this fact may be to a visitor looking for experimental new communities of the future, it is the logical result of what in many ways has been a highly successful urban policy in Britain. The industrial revolution left British cities as overcrowded, dirty and unwieldy as any in the world. Its citizens badly needed new housing and access to fresh air, green grass and the backyard gardens that are a British institution. Ebenezer Howard showed the way with his proposal for “garden cities” in the countryside, a utopian plan for rearranging housing densities in an open, green setting that was made feasible by the inclusion of commerce and industry in each project.

Letchworth was founded first, 35 miles north of London, in 1903. Then Welwyn Garden City, not far away, was begun in the 1920s. Despite many problems, both projects, launched privately without government support, worked out financially and provided housing, employment, shopping and community services in the open, green suburban fashion envisioned by Howard. The British government got into new town building after World War II by setting up public corporations to take over and expand Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City, and to develop from scratch many more new towns in England, Scotland and Wales. Despite the passing years and changing urban theories, the basic lines of British new towns, now widely copied all over the world, have changed little since the first prototypes.

They are collections of neighborhoods built around a town center core that has evolved from shops placed around a town green to shops placed around a concrete pedestrian mall. The automobile is the primary mode of transportation, and the land use design of British new towns, from Howard’s garden cities to Milton Keynes, has always begun with and been determined by the design of a system of roads for cars and buses. British new town planners have, however, pioneered in creating auto-free pedestrian areas in their shopping centers, building homes facing away from auto streets, and providing separate circulation systems for pedestrians and cyclists, innovations that were consistent with the garden city (and American suburban) philosophy of escaping from big city nuisances. Employment for residents and income for each new town is provided by businesses in separate industrial zones, which served as models for the more recent “industrial parks” of U.S. suburbs.

Each new town is developed by a public corporation created and financed by the British government under post-war new towns legislation. Each corporation has the full authority and sufficient capital loaned by the government to buy the needed land and develop all public and private facilities for a complete town. Local government funds and other national grants help pay for roads and public utilities, while private developers, supervised by the new town corporation, build much of the housing, stores and factories. The public corporation, which retains ownership of much of the land and buildings, uses the income from sales and rentals to pay back the government loans so that money can be lent to other projects. No new town corporation has failed to fulfill its obligations yet, and several, after having paid for themselves and realized a surplus, have been dissolved. These projects are then taken over by a British government New Town Commission which will manage them indefinitely, using rental income to maintain public facilities and, when possible, make improvements. Nearly 400,000 people now live in British new towns, with many of them working in the nearly 40 million square feet of new factory and office space in the new towns.

For all their outward resemblance to U.S. suburbs, the British new towns work better. In the first place, they did not just grow up haphazardly; they have been put where everyone agreed they were needed and would do the least violence to the British countryside. Around London, for instance, the new towns were located beyond the “greenbelt” of protected parkland, farms, open space and tiny old villages that ring London. These new towns – Crawley to the south, Bracknell to the west, Basildon to the east, and Stevenage, Hatfield, Harlow, Welwyn and Milton Keynes, among others, to the north – have succeeded in drawing population and industry beyond the greenbelt rather than into it. In locating new towns outside Glasgow, Scotland (Irvine, East Kilbride and Cumbernauld) and Newcastle in northeastern England (Washington, Peterlee and Aycliffe), among other cities, the government also has attempted to channel the suburban growth of these cities to the best pre-planned sites, while protecting open space and quaint villages elsewhere around these cities from uncontrolled urban sprawl. In fact, rather than deprive the Newcastle area of its precious few unspoiled open spaces, Peterlee and Washington are located on played out coal fields (and, as a result, have each created worldwide interest in the ingenious methods they have used to build on ground that has been badly scarred and undermined). Northwest of Birmingham in the heavily industrial Midlands, the new town of Telford is to replace ghost towns of abandoned ironworks.

The British have successfully used some of their new towns to relieve overcrowded conditions in working class neighborhoods of the big cities and provide many of their residents with better homes. Planners arrange for the combined transfer of willing businesses and their employees from London’s wharfside East End to Harlow or Stevenage, for instance, or from Merseyside slums in Liverpool to the quite new project of Runcorn, just across the Mersey River. In the case of projects like Washington, just south of Newcastle, the new town corporations have succeeded in drawing new businesses (Timex, RCA, Proctor and Gamble and Phillips Electric among others) to areas where working men were left without jobs following the collapse of old industries. At Cumbernauld, skilled and trainable workers with unsatisfactory or no jobs in depressed Glasgow were matched with employers, including IBM, attracted by the location, low rents, new roads and other advantages of a new town. In some places, the move of people and industry to the new town was so well coordinated that as high as 85 percent of the new town residents (in Harlow, for instance) work at jobs inside the new town itself, and continue to enjoy some of the shared interests and friendships of the old big city neighborhoods from which they came.

However, this very success in matching workers and jobs has made many of Britain’s new towns single class communities. To move into most of them, a prospective resident must be assured a job by one of the new town’s largely technological or clerical employers; thus the population of each project is disproportionately dominated by white collar and skilled workers. There are few non-skilled workers, non-whites or immigrants of any kind, low income families or, at the other end of the spectrum, upper income people. Although this is not particularly disturbing to the British, who readily segregate themselves by social and economic class, the sameness of everyone and everything in each new town bores and disconcerts the visitor, reminding him too much of the economic stratification, and resulting sterility, of too many American suburbs.

The lack of opportunities for unskilled and lower income workers does leave real problems back in the central cities. In the East End of London, for example, from which skilled, middle income, white workers were attracted to new towns like Harlow and Stevenage, mostly low income and jobless Pakistani, Indian and black immigrants remain today, trapped in ever worsening ghetto-like conditions. In this respect, just like U.S. suburbs and new town projects, the British new towns have exacerbated rather than eased a critical urban problem.

Although most British new towns do not appear radically different at first glance, they actually have been the source of a wide variety of experiments. The most important and visible, of course, is the garden city concept itself, characterized chiefly by dense, low-rise residential neighborhoods with a minimum of individual family “garden” space located not far from large public green spaces. The large protected open spaces range from town commons, playing fields and parks to preserved farms. Along the main traffic artery of Harlow cows graze only a few hundred yards away from the large central shopping mall. The often unimaginative building design of the older projects is softened by the trees and grass flourishing everywhere, giving each new town considerable “home in the country” atmosphere without parceling out to each family huge, expensive and often wasted plots of ground.

British new towns also pioneered, along with a few American garden suburb projects like Radburn, New Jersey, in the separation of pedestrian and vehicle traffic. Housing was built facing pedestrian paths, with auto roads and parking behind. The paths were the most direct routes to school or the store, while the streets curved indirectly to them around the perimeter of built-up areas. A recent study by the non-profit British Housing Research Foundation showed that residential neighborhoods that can be crossed on foot are three times safer than traditional housing arrangements alongside auto streets. In Stevenage, which long boasted the world’s most complete network of separate foot and bicycle paths, the residents own more bikes than cars (although its ratio of cars to households is still above Britain’s national average).

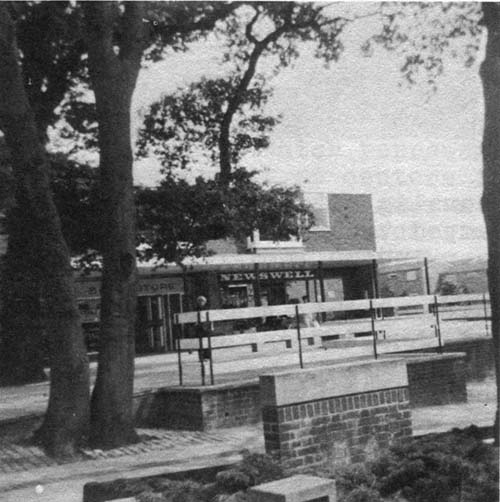

Stevenage: Lots of trees and green open spaces, separate pedestrian walks everywhere, clumps of convenience stores dropped in amongst the houses, and public gathering places in the center of its pioneering pedestrian mall shopping center.

Yet auto-pedestrian separation remains vastly unpopular among Britons, who, like American suburbanites, prefer to be able to drive their cars up to their front doors. Thus, although some of the more recent new town projects, like Cumbernauld in Scotland, have two complete community-wide circulation systems, others, like Milton Keynes, have turned almost completely away from the idea and promote the fact that their residents will be able to drive directly from their front doors to the door of any shop or other facility in the entire community. Only within each small neighborhood of Milton Keynes will there be footpaths, which will take children to the local grammar school.

A more popular British new town innovation is the “adventure playground,” first tried in Stevenage and now being copied throughout Britain. An adventure playground is a plot of ground set aside for a certain age group of children and furnished not with shiny, special purpose playground apparatus, but rather with the raw materials of youthful fantasy: various size pieces of lumber, rope, old auto tires, old cars themselves, shovels, saws, hammers and other tools, and any other odds and ends that might be available. To an unimaginative adult, the average adventure playground looks like a junkyard; to a child it is an endlessly fascinating and ever changing world of his own making. Studies in England show that while adventure playgrounds cost less and actually use less space than conventional playgrounds, they are consistently used by more children for longer periods, whether in the green, leafy suburban setting of a new housing estate on a scenic hillside in Stevenage or on a cramped vacant lot hemmed in by office buildings in one of the lower income immigrant neighborhoods of London’s West End. The adventure playground is one by-product of British new town building that the United States has not yet widely duplicated, but should soon.

Picture of an “adventure playground.”

Much more extensively copied in the United States is another British new town innovation: the central mall shopping center. Although the Stevenage center was the model for many early U.S. suburban shopping malls, the art has been so rapidly and thoroughly refined in the United States that British designers have recently been visiting America for tips. One result of this cross-pollination is the completely covered, climate-controlled shopping mall in the center of Runcorn outside Liverpool. Its enclosed design is obviously based on those for the many indoor mall shopping centers of the United States, while its several levels of garage parking hidden under the center, in place of acres of outdoor parking lot, is a feature of newer European centers that U.S. planners should copy in more places.

The British new town centers are more than shopping centers, however. They also contain some of the social, recreational and civic facilities, along with office employment, that had always made village and town centers the focal points of British urban life. When vitality seemed to be missing in the early new towns, provision was made in some of them for a market square where the popular outdoor pushcart markets of older towns and inner city London neighborhoods could be duplicated. Town squares of benches, flowers, kiosks and outdoor sculpture were also added. British new town centers are still often rather lifeless, however, particularly at night, because few of them have any places in them where people live. They have also tended to have far fewer cinemas than comparably sized towns or sections of big cities, and even relatively few pubs, which are, of course, among the most important public social institutions in Great Britain.

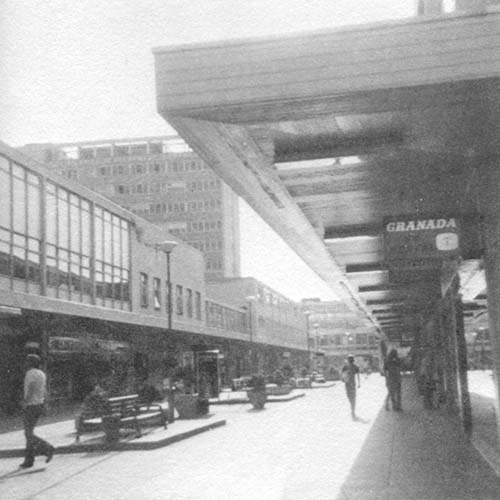

The covered Runcorn mall, for its impressively functional modern design and variety of commercial outlets, is particularly lacking in social life. A large, three-story space set aside in the middle of it as a “town square” is nothing more than a big room; it should have been at least partially opened to the outside somehow and fitted out with pushcart-like stalls, a pub or two and other trappings of town center life. Perhaps even more important, there should be some housing in or near the Runcorn center, so as to people it around the clock. Yet it is noteworthy that the Runcorn center opened precisely on schedule, before the population of the new town exceeded a few thousand, which represents a significant advance over the slow development of centers in older new towns, where residents often waited years for adequate shopping facilities and the few eating spots and other social amenities already available in the Runcorn center. This fact has undoubtedly been one reason why surveys of new Runcorn residents turn up fewer complaints of “new town blues” – the feeling of isolation that new residents, especially women, often suffered in older British new town projects.

Another reason for the strong sense of a Runcorn community reported by the early arrivals is that most of them come from the same rundown working class neighborhoods in Liverpool. They may not already know each other personally, but they know the same streets, had complained about similar dilapidated housing back in the city, had feared the same vandals and hooligans. In Runcorn, where they have moved after winning jobs with the industry transferring there, they find new housing with the complete bathrooms that many never had before, telephones that work and lush green landscaping that nobody is trampling; all this along with the shiny white hulk of Shopping City. Runcorn represents the chance for somewhat upwardly mobile working class families to escape from the Liverpool slums into the promised land of the English countryside.

Back in Liverpool, however, the social workers and community planners who are active in the neighborhoods which are losing residents to Runcorn complain that, once again, a new town is skimming the cream off the top of a downhill-sliding inner city area while leaving all the problems and problem families back in the city. Runcorn’s development, they argue, should have been considered in planning of a larger scope for the social improvement of the entire Liverpool area, rather than being allowed to become a sanctuary for those families lucky enough to run from inner LiverDool.

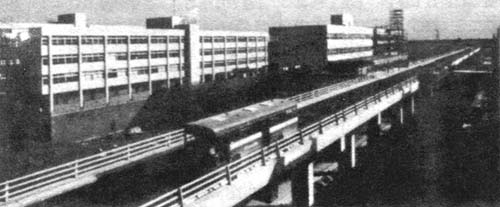

RUNCORN’s enclosed Shopping City town center. Note the elevated busway leading into and out of it.

These complaints about a lack of social planning have been lost for the moment, however, in a growing British euphoria over the physical planning for Runcorn, which is considered one of the most attractive new towns now under way. Not only are Shopping City and the project’s unusually attractive housing estates widely praised, but so is Runcorn’s most important urban planning experiment, its completely separate road system for buses. Runcorn’s “busway” is a two-lane road, elevated in some places, that traces a figure-8 through the project, with the crossing in the middle of the 8 coming at Shopping City in the center. The busway is completely separate from the auto road system and has the right-of-way in the few places where the two cross. The only stops the buses have to make are when they pick up and discharge passengers. Thus, riding the bus is the most direct and fastest way to go most places in Runcorn, especially to and from Shopping City and most of the factory and office areas, which are clustered around stops on the busway. At Shopping City, the elevated busway passes right through the enclosed mall, where the buses’ central station is, with escalators connecting the bus station level with the levels for shopping and car parking. The Runcorn busway is cheaper than a rail public transit system, and apparently more efficient than running buses on regular streets. It will be interesting to see, as Runcorn grows, whether the busway will become the dominant transportation means in Runcorn and thus reduce the need for auto use there.

In other new towns, too, the British are belatedly becoming interested in increased bus transportation, after watching cars almost completely overrun many projects. In spread out Stevenage, the local government has subsidized a “superbus” experiment in which express buses charging unusually low fares picked up residents of a particular cluster of residential neighborhoods and then whisked them non-stop to the town center and to the project’s large industrial park. The fares were so low and the buses so frequent that they became quite popular; residents of neighborhoods outside the experiment petitioned for their own superbuses. To merely continue, much less expand, the project, however, a larger public subsidy is needed and no governmental authority has yet offered it.

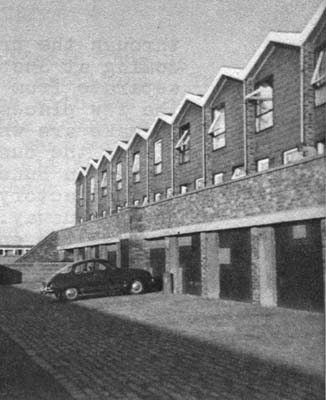

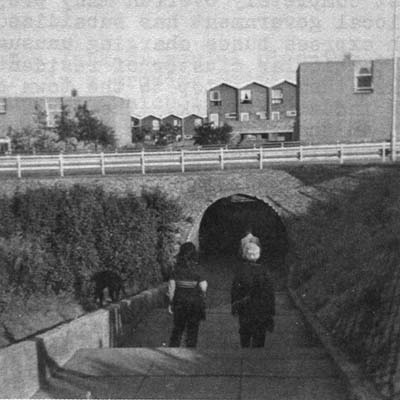

In Cumbernauld, perhaps the most widely known and truly experimental British new town project, planners met head on the problems of the automobile and the sterile suburban atmosphere of most of the new towns. Making use of Cumbernauld’s location on a high hill east of Glasgow, they decided to build the modern equivalent of a medieval hillside town. Cumbernauld is being tightly built around its center, with three-fourths of its planned population of 70,000 people to be living within three quarters of a mile of the hilltop center. The project has rigidly segregated auto and pedestrian circulation systems, with all the footpaths leading directly by the shortest possible routes to the center.

Like the center of a medieval town, Cumbernauld’s center was to be bustling with almost around-the-clock activity. Apartments, offices, recreational facilities and stores were all built into the huge first stage of the maze of interconnecting buildings. The center’s architectural complexity, with its offset levels, narrow corridors and spacious malls, twists and turns, closed and open spaces, ramps and stairs, was intended to duplicate the meandering little streets and changing levels and perspectives of hilltop medieval towns. It was thus expected that the project’s layout would compel residents to walk to the center, and that the spatial, commercial and social variety they would find would keep them there.

CUMBERNAULD: A world of concrete and stone, walkways and freeways, on a high, windy hill east of Glasgow.

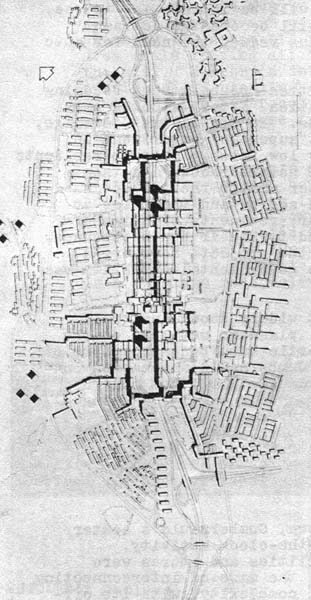

Plan of Cumbernauld. Note dependence on freeway system.

But Cumbernauld has not fulfilled these expectations. Scotland is too cold, rainy and windy a place for an exposed hilltop town. The steep climb from all directions to the town center is too difficult to make with baby carriages or laden grocery carts, and often is too dangerously slippery without encumberances in bad weather. Although the stores, offices and apartments were put right into the first stage of the center, relatively few social facilities, outside several bars in a new hotel, were opened. So, while the world’s architects visited, studied and debated the unusual Cumbernauld center, the community’s new residents got into their cars and drove elsewhere to shop and play.

Cumbernauld now has the highest rate of car ownership and use in Scotland. Its residents have turned their backs on its famous center to live most of their out-of-home lives elsewhere in nearby suburbs of Glasgow. They are not terribly unhappy about it all, however, shows a study conducted for the British Urban Research Bureau. Cumbernauld residents, who like the newcomers to Runcorn, have moved out to the new town from cramped, rundown neighborhoods of the big city, in this case Glasgow, like their new housing in Cumbernauld, their jobs in the largely American-owned industry there, and the ease with which they can travel on Cumbernauld’s new auto roads out to the freeways leading into the lake-filled Scottish countryside. Inside their homes, they are proud of their wall-to-wall carpeting and new furniture, and they spend much of their time watching television. Outside their homes, only the children, who roam unsupervised far and wide, populate the much praised system of pedestrian paths.

The unexpected results of the Cumbernauld experiment have led Britain’s new town planners to abandon all interest in innovative community forms and return to building bigger and better suburbs more suited to the growing British fondness for automobile transportation. Cumbernauld and Runcorn, although both far from completed, are second generation new towns conceived in an experimental planning mood in the late 1950s and early 1960s as a variation of the basic garden city design of the projects begun right after World War II, such as Stevenage and Harlow. Now the British are beginning construction of the so-called “Mark Three” or third generation new towns, which in fact are reversions to the suburban garden city mold, only much larger and much more closely tailored to the demands of the automobile.

The best known Mark Three project, Milton Keynes, is still in the late stages of planning, although its most important proposed features have been made public: its nerve system of auto freeways and its sprawling, two-mile-long town center of stores, offices, public buildings and a stadium, and parking in front of every store and building. At an exhibition of Milton Keynes plans held in London last summer, a slide show emphasized the size of the proposed center by showing how the Great Pyramid, St. Paul’s Cathedral, Wembley Stadium, Trafalgar Square, the Piazza San Marco and many more of the world’s better known sizable public landmarks could be fitted into an area the size of the Milton Keynes center, with plenty of space left over. If the design team “had set out to show the inhumanity and megalomanic scale of their plan they couldn’t have thought of a better way of doing it,” wrote one critic in The Architects’ Journal.

A lack of humanity, warmth or spark of life in public places is perhaps the most telling characteristic of too many British new towns. They provide their residents with solid new homes, inside which they are making what they say are satisfying new lives, but the overall strong sense of community so easily recognized in established British cities and towns is missing in too many of the new towns. There seem to be two reasons for this: the overdependency on physical planning for the new towns and the conservatism resulting from the determination that each new town corporation pay its own way.

The British are proud that their new towns pay their own way. This fact has made so large a new town program possible during a period when Britain has been adjusting to having a relatively more limited national economy. To accomplish this, however, the direction of the new town corporations has necessarily been conservative – dominated by government bureaucrats and retired military officers. To be sure of selling and renting land and buildings quickly enough, the first priority in planning has been to satisfy the public’s most obvious demands, including greater freedom for auto transportation. Experiments that do not immediately succeed are scrapped, even if, as seems to be the case with Cumbernauld, it may be the manner in which the experiment was carried out rather than the basic idea that is faulty.

The emphasis on nuts and bolts practicality has led also to a dependence on physical planning – road systems, arrangements of housing estates, shopping centers and the like, which show their worth in pounds and pence – at the expense of social planning. The “new town blues” suffered in so many projects are the consequence of there being so little to do socially, of so little satisfying contact with other human beings. The Cumbernauld experiment failed because only its physical design was being considered and not the social factors which, in the end, were the reasons why Cumbernauld residents turned their backs on their shiny space age center.

Some new towns have become notable social successes largely through luck. In Harlow, because most of the industries there had moved lock, stock and barrel with most of their employees from the same area of London, the residents already knew one another and shared interests. It therefore was natural and easy for them to form the many social and service organizations for which Harlow is famous. It is this network of voluntary associations, rather than anything different physically about Harlow, that makes it a real community.

Plan of Cumbernauld. Note dependence on freeway system.

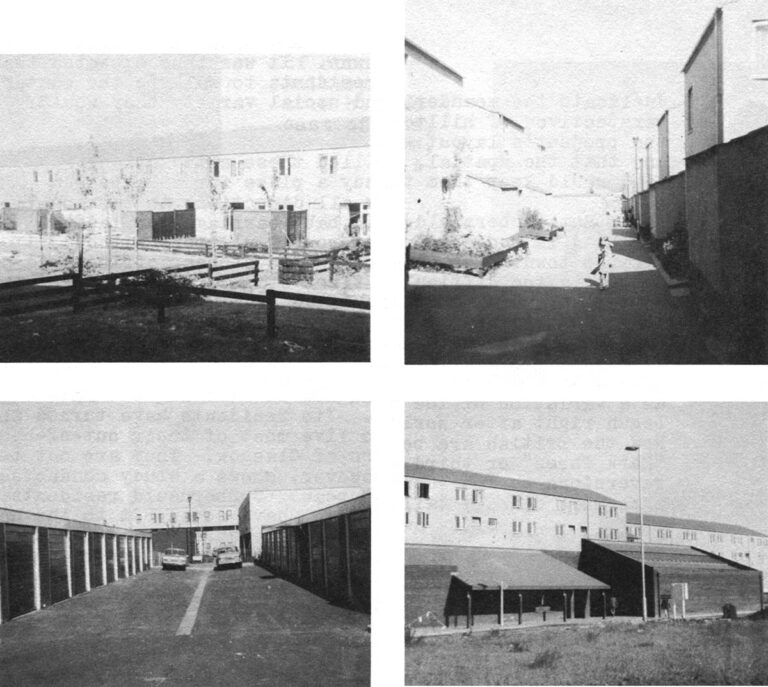

East Kilbride shopping center.

In East Kilbride, southwest of Glasgow, the residents turn much more to facilities inside their own community than do the residents of Cumbernauld, even though East Kilbride was not so radically designed to try to force its citizens to come together in one place. A principal attraction of East Kilbride for its residents is its unusually complete recreation program, with a huge covered town natatorium and gymnasiums and recreation halls scattered in various neighborhoods. Its much more conventional shopping center, surrounded by sprawling parking lots, is doing quite well.

The British planners look at the economic success of East Kilbride, however, and notice its lack of rigid auto-pedestrian separation, its conventional suburban shopping center with outdoor parking and its overall lack of experimentation. The conclusion they draw is that the conventional ways of doing things are popular and involve less investment; from this comes Milton Keynes, the suburb writ large. Thus, the British are ignoring the dire consequences of continuing to tailor make more and more of their new urban development to the automobile. They are moving away from further experiments in finding solutions to important urban problems in their new towns. They are refusing to see if social research might turn up answers that would sell well to prospective new town residents and also make progress in building truly better, socially integrated and lively new communities. This is the overriding disappointment of the British new towns, even though they may work better as attractive, well-ordered suburbs than their American counterparts.

Received in New York on November 1, 1972

©1972 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. was an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, the Post and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.