Margaret Edds

- 1985

Fellowship Title:

- Black Political Power in the South

Fellowship Year:

- 1985

Doug Wilder’s Campaign

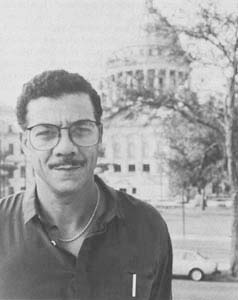

RICHMOND, Va.–On a cloudless late October day, Paul Goldman steered his cluttered compact through noontime traffic in the Confederate capital and contemplated the storm gathering on his personal horizon. Goldman, a transplanted New Yorker who had almost single-handedly managed Douglas Wilder’s historic campaign for lieutenant governor of Virginia, knew that victory astonishingly was within grasp. Seven days remained, however, and forces were massing that, in a week, might crush Wilder’s hopes of becoming the first black elected to statewide executive office in the South in the 20th Century. The artillery for the anti-Wilder blitz would be a series of ads Goldman had just watched, grim-faced, in a Richmond television studio. Throughout the summer lull and into the quickening pace of the 1985 fall campaign, Wilder’s opponent–a congenial, if ineffectual state legislator–had avoided personal assaults. Now, however, John Chichester appeared on the brink of losing the unlosable race. Decorum had become an unaffordable luxury. For weeks, Chichester had refused to exploit what his campaign manager and others insisted were “golden issues” against Wilder. The ads Goldman

Another America

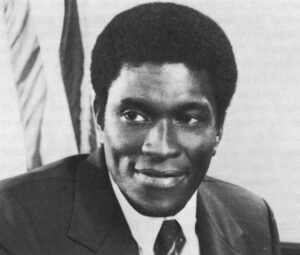

SUNFLOWER COUNTY, Miss.–The faces at the courthouse in this languid and historic central Delta county seem largely untouched by time. On Mondays, Joe Baird, John Parker, Jim Corder, Edgar Donahoe and Billy Cummins gather for supervisors’ meetings. Like generations of local officeholders before them, they are mostly farmers, men whose fortunes spring from the dusky, alluvial soil swept here thousands of years ago on the floodwaters of the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers. In century-old tradition, as well, all five are white. Across the hall is Sheriff C.O. Sessum’s office. He too is white. So are Circuit Clerk Sam Ely and Chancery Clerk Jack Harper, the county’s dominant political figure. They are not alone. The county tax assessor, the coroner, the superintendent of education, the two justice court judges, the five constables, the five election commissioners, and four of the five elected members of the school board are also white. Jack Harper, Circuit Clerk in Sunflower County, Miss. There is, in fact, one black elected official–school board member Lonnie Byrd-in all of county government. In the

Life in the Black Belt

TUSKEGEE, Ala.–In 1974, on the day the mayor and the councilmen christened the Tuskegee Industrial Park with flowery speeches and a stone slab marker, Jim Roberts stood in the doorway of his rustic, pine-sheltered grocery and watched. Promises of new industry and jobs and a better life drifted across the highway, and Roberts felt the breeze of change. “At least, I was hoping so,” he recalled. Eleven years and hundreds of thousands of federal dollars later, the marker has been joined by an electrical substation, water hydrants, a high-pressure gas line, an airport landing strip and an industrial-sized hanger–everything, in fact, but industry. Only two tiny firms, both black owned, have set up shop. Combined, they employ just over 50 people. Mostly, the park remains in its natural state, a preserve of wild oats, scrub brush, red-clay dirt and towering pines. Across the way at Roberts’ grocery, life continues its slow, unfettered pace. Dreams of lathe operators and computer technicians pulling up for gas or a Mello Yellow–maybe even, a week’s groceries–have long since died.

The Path of Black Political Power

Framed by Georgian mansions and brick streets, the statues of Richmond’s Monument Avenue stand in tribute to the ruinous glory of this city’s Confederate past. There is Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson, the dour, but brilliant tactician, hero of battles at Chancellorsville and Bull Run. In sculpture, he is mounted and defiantly facing north. Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, stands slender, tall and erect, his right arm extended in welcome. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, deeply religious, romantic, dead at 31, is a study in youthful vitality. His cape is flung jauntily back; his steed stamps with high spirits. Tallest is Robert E. Lee, general-in-chief of the Confederate armies and the noble embodiment of a region’s lost cause. So beloved was Lee that a 19th-century Virginia governor ordered the general’s statue redesigned, rather than have it stand ten inches shorter than a nearby monument to George Washington. Fifty Confederate generals and an estimated 25,000 people from every Southern state attended the Lee statue’s 1890 unveiling. And so, some 75 years later, in the mid-1960s, as word spread that