Framed by Georgian mansions and brick streets, the statues of Richmond’s Monument Avenue stand in tribute to the ruinous glory of this city’s Confederate past. There is Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson, the dour, but brilliant tactician, hero of battles at Chancellorsville and Bull Run. In sculpture, he is mounted and defiantly facing north. Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, stands slender, tall and erect, his right arm extended in welcome. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, deeply religious, romantic, dead at 31, is a study in youthful vitality. His cape is flung jauntily back; his steed stamps with high spirits.

Tallest is Robert E. Lee, general-in-chief of the Confederate armies and the noble embodiment of a region’s lost cause. So beloved was Lee that a 19th-century Virginia governor ordered the general’s statue redesigned, rather than have it stand ten inches shorter than a nearby monument to George Washington. Fifty Confederate generals and an estimated 25,000 people from every Southern state attended the Lee statue’s 1890 unveiling.

And so, some 75 years later, in the mid-1960s, as word spread that blacks were on the verge of political control in this Southern citadel, thoughts turned with dismay to the statues. Would those icons of a revered past be destroyed? The 1968 General Assembly moved swiftly and quietly to ensure that they would not. Asserting that “the traditions and memorials of (state) history are in the public interest of the people of the Commonwealth as a whole,” the legislature decreed that the attorney general–not local councilmen–had ultimate control over Virginia’s historical monuments.

The statues were safe.

That legislative act was only one of the ways, both great and small, in which the offspring of Southern generals and foot soldiers prepared for the transfer of political power in the Confederate capital into the hands of the great-grandsons and great-granddaughters of former slaves.

RICHMOND, Va.–The headline that greeted city residents on the morning of March 5, 1977 seemed calculated to send a new round of shudders through corporate boardrooms and whites-only neighborhoods already reeling from the week’s election returns. “Power to the People,” the Richmond Afro-American triumphantly proclaimed, raising a verbal clenched fist to a city and state steeped in the virtues of patrician, oligarchic rule. Nine faces–five black, four white–peered from the page, recording an historic first. Never before had a Southern city elected a black council majority to do its business.

The Afro-American’s response was both a measure of the momentary euphoria and a foreshadowing of the bitterness to come. “An era dominated by narrow-minded, racist politicians who served only the white elite and their business interests at the expense and suffering of black people and poor white people, has ended…hopefully forever,” wrote Editor Raymond Boone.

Today, eight years after Richmond’s political revolution, an overthrow spawned by the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, the prophesies for this city remain unfulfilled. Black progress in Virginia’s capital has fallen shy of expectations. To be sure, the political shift has brought a tide of black faces to city hall and a spate of city contracts to minority-owned firms. But the transfer of power from whites to blacks has proved more painful and the acquisition of power less absolute than many blacks envisioned. A voting majority at city hall has done nothing to erase segregation in the high-toned, azalea-filled neighborhoods of west Richmond, where household income is four times that of the city as a whole. Nor has it eliminated the knots of unemployed black men, standing idly at midday amidst the abandoned houses and garbage-strewn lots of the East End. It has not stopped a steady erosion of white support for public schools, which this year are 86.4% black. And it has not reduced the number of black Richmonders who live in poverty.

Nor has black political power prevented a growing disparity between black and white incomes, reflecting an exodus of white middle class families. In the 1970s, black family income slipped during the decade from 71% to 60% of that for whites. By 1980, median income for Richmond’s black families was $12,643. For white families, it was $21,215.

And yet, for all this, Richmond and its residents–both black and white–have lurched stubbornly forward. The city (pop. 219,000, 51% black) “will die if the Negroes take control,” one influential writer for the afternoon newspaper predicted before blacks won political control. Instead, Richmond as a whole is flowering economically, even as blacks struggle to turn political clout into economic gain. A nearly completed hotel-convention shopping complex, featuring one of developer James Rouse’s glass-and-light pavilions, is prompting a spirit of downtown revival. And the design, bridging Broad Street, the traditional dividing line of black and white Richmond, is a tribute to dreams of a more racially unified city.

Even though “blacks expected a lot more to happen…things have changed for people who have the resources and know how to get around,” concluded Randolph Kendall Jr., executive director of the Richmond Urban League. “Poor folks,” he added, “they’re still lookin’ for a place to stay.”

In some ways, Richmond’s odyssey has paralleled the evolution in other Southern cities–Atlanta, Birmingham, New Orleans–which have elected black mayors, black council majorities or both in recent years. In other ways, Richmond’s story is uniquely its own. As elsewhere, the racial shift on the city council has given blacks a role heretofore unknown on boards and commissions and in city offices. Whites still hold a disproportionate share of the top-paying city jobs, but the gap is narrowing. Of the 30 highest ranked positions, blacks hold 12, versus four in 1977. City construction contracts awarded black firms are up from 3% in fiscal 1981 to 30% in fiscal 1984, according to purchasing officials.

Also paralleling other Southern cities, Richmond saw its early transition marred by a deeply polarizing event. In Birmingham, it was Mayor Richard Arrington’s 1981 endorsement of an all-black slate for five council vacancies that sent whites into orbit. In Atlanta, former Mayor Maynard Jackson’s attempt to fire an Old South police chief rallied conservatives. In Richmond, the black majority’s 1978 firing of a white city manager prompted outrage among Main Street businessmen. And as elsewhere, initial confrontation has gradually evolved into a degree of racial accommodation.

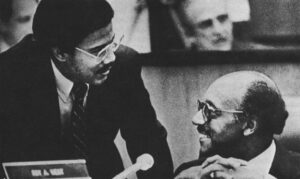

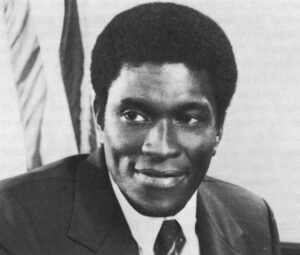

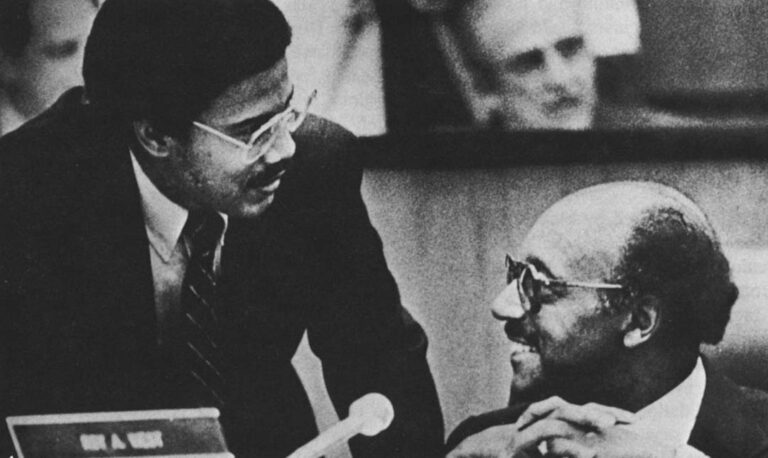

In two ways, however, Richmond’s political evolution stands apart. One is the unexpected 1982 election of a black mayor whose power base rests mainly with whites. Roy A. West, a black middle school principal and political novice, that year attracted mostly white votes in winning one of nine ward seats. Taking office on a pledge to end council bickering, he promptly joined with the four-member white minority to elect himself mayor. The move was a stunning setback to the black majority, led since 1977 by former Mayor Henry L. Marsh III, one of the state’s leading civil rights lawyers. The shift has pleased whites, but blacks remain sorely divided about its consequences.

The depth and persistence of acrimony on the Richmond council also seems unique. Dozens of key votes–involving appointments, redistricting, utility billings for the poor, school appropriations, a residency requirement for city employees, expense accounts, and so on–have broken down along racial lines. Former City Atty. William Hefty estimates that the city spent roughly $200,000 between 1978 and 1984 defending council members in lawsuits filed or encouraged by other council members. At times, public threats and insults seemed commonplace. Only in the last two years has the hard line, factional voting relaxed somewhat.

While many blacks blame white racism for the hostility, whites credit personal and philosophical differences. No one disputes, however, that blacks came to power at a time when tensions were high. “Richmond had just been a city under stress for six or seven years,” said Councilman William J. Leidinger, elected in 1980, two years after his explosive firing as city manager. A 1969 annexation, negotiated largely in secret, had brought 47,000 new residents–mostly white–to the city, as well as a legal challenge under the Voting Rights Act. That act forbids election law changes aimed at diluting the impact of black votes.

The U.S. Supreme Court responded by blocking Richmond’s council elections until the legal challenge was resolved. In a case unique in U.S. municipal annals, no elections were held from 1970 to 1977. Finally, the court held the annexation racially discriminatory and oversaw a switch from at-large to ward voting. Meanwhile, white Richmond was in an uproar over court-ordered school desegregation, including an eventually aborted plan for county and city school consolidation.

Against that backdrop, the new council took office on March 8, 1977. Not the least of the members’ problems, it emerged, was the fact that many of the nine–despite prominence on their individual turfs, despite even having grown up in the same city–were strangers. Seven whites and two blacks served on the outgoing council; five blacks and four whites on the new. The disparities in backgrounds and interests were as striking as the difference in color.

Among the departing white majority were the president of a Main Street brokerage firm, a retired oil company executive, the president of one of the city’s best-known realty firms, the owner of a prosperous automobile dealership, a building materials company executive, and the president of a major funeral home. In dramatic contrast, the new black majority included a civil rights lawyer, a postal workers’ union official, two social workers, and a 28-year-old Vietnam veteran, then completing his bachelor’s degree.

Henry L. Valentine II and Claudette Black McDaniel exemplified the old and the new. Valentine, who served on the outgoing council and returned as vice-mayor during 1977, is a member of one of Richmond’s most established white families. His ancestral home serves as a museum of the city’s history and art. President in 1977 of a prosperous, downtown brokerage firm, Valentine grew up in the city’s posh West End. In 1949, he won the city tennis championship and a few years later, he shared the title at the Country Club of Virginia. At the University of Virginia, he was president of the student body. Conservative, bluntly honest, highly civic minded, Valentine is an example of white Richmond’s best and brightest.

Claudette McDaniel, elected in 1977, might well have come of age in another country. Her father was a chauffeur who was making $50 a week when he retired; her mother, a housewife. She grew up with four brothers, ample love, boundless confidence and little else in a black section of south Richmond. “Dogtown,” she says softly, recalling the neighborhoods nickname. Her smile is as wide as Dixie, but there is an edge of challenge in her voice. “Yeah, dogtown.”

Seated recently in her office at the Medical College of Virginia, where she is an occupational therapy section chief, McDaniel was typically exuberant, even a tad outrageous. She was wearing a gold knit tube dress, tan boots, loop earrings, and grape polish on eight of her ten fingernails. Two were painted gold. “Communications were pretty poor,” said McDaniel, who is now vice-mayor and has proved to be a capable, steel-edged politician. “Whites didn’t know the general black population. There’d always been a few ‘acceptable’ blacks that they dealt with. They didn’t know a Claudette McDaniel. I came from the wrong side of the tracks.”

What many whites felt they did know in 1977 was that the group of blacks just elected was incapable of running the city. Many said so privately. A few, like Valentine, admitted as much. Valentine recalls a meeting which both he and McDaniel attended, not long after the black majority took office. “After it was over, she came up and said, ‘You don’t think we blacks can run the city, do you?’ We sat and talked for a long time. And I said, ‘The fact of the matter is, I don’t. The fact of the matter is, you haven’t had the experience.’ ” The conversation was a measure of how far Richmond had to go.

City council journals record that the opening days of the new administration was relatively calm. In the first six months, only six votes followed strict racial lines. The bitterness in subsequent years more than compensated for that honeymoon. Before two years were up, the Richmond News Leader’s editorial page was routinely referring to the black majority with such epithets as “monkey-see, monkey-do leaders of a banana Republic” or “a bunch of clowns in a Chinese fire drill.” Valentine, in a September 1979 newspaper commentary, maintained: “The present majority on city council has compiled such a dismal record that it borders on incompetence at worst, and a serious lack of good judgment at best.” And the majority was reduced to tactics such as an August 1979 resolution, passed 5-3, urging white members to end “unfounded allegations designed to create an atmosphere of suspicion and…racial animosity.”

At the center of the whirlpool was Mayor Marsh, a slightly-built, whispery-voiced minister’s son who came of age in Jim Crow Richmond. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Marsh represented plaintiffs in about 100 Virginia school desegregation cases. Even today he and his family maintain their home only blocks from some of Richmond’s most squalid slums. As mayor, Marsh moved quickly to change the role from one of ceremony to substance. A divided council approved his hiring of a $30,000 assistant. He was in and out of Washington, DC, winning millions in federal grants. At home, he pushed for a revision in the state funding formula, for downtown redevelopment, and against federal highways circumventing the city. The 1978 firing of city manager Leidinger, Marsh recalls, brought a tense summit with Main Street businessmen and a warning–proved erroneous–that “blood would flow in the streets.” The financial district was equally aghast in 1981 when the black majority blocked plans for a downtown Hilton Hotel that, the majority feared, might jeopardize their own development agenda.

“Marsh just tried to run rough-shod over the other members of council,” complained former Councilman G. S. Kemp, who once spent $2,500 trying to block a majority-sponsored grant to a now-defunct theatre company. “Instead of having a white slave master, we had a black one,” said Councilwoman Carolyn Wake, a white member.

The counter-view is Urban League director Kendall’s. “Marsh was an NAACP lawyer. He saw a lot of things in these cases. He felt he had to do some things to make people realize he wasn’t going to be pushed around. People couldn’t deal with it.”

At least one corporate outsider lent a more dispassionate view. Hays T. Watkins, board chairman of the CSX Corp., hesitates only slightly before using the word “stable” to describe Richmond politics during the Marsh era. CSX, a railroad holding company, now Virginia’s largest corporation, was aware of the historic tensions being played out on city council when it chose Richmond as its corporate home in 1980. “But having lived in Cleveland, we had seen major problems,” he said. Watkins knows many Richmonders disagree, but “we felt the political scene was stable.”

The Marsh era ended abruptly and unexpectedly in 1982. Political leaders–both black and white–were surprised when a little-known middle school administrator, never heavily involved in civil rights activities, defeated a member of the black majority and was elected mayor. White conservatives could scarcely believe their luck; black liberals were appalled. In the interim, Roy West has proved a strong defender of minority set-asides in city contracting. He has also voted frequently with whites on appointments and budget matters. Continuing division over his leadership reflects a growing national split between civil rights era black leaders and coalitionists willing to work in tandem with whites. It mirrors, too, growing economic divisions among blacks. West represents a middle class district; Marsh, a poor one.

It is, indeed, on the economic front that the limits of black political power are most sorely tested. A 1982 report by two Virginia Commonwealth University professors suggests how far black Richmonders have to go in penetrating the city’s economic power structure. J. John Palen and Richard D. Morrison surveyed the 115 highest-profit corporations headquartered in Richmond. Of 1,547 officers, board members and executives, 24–1.6%–were black. Moreover, all but nine of the blacks were employed by a single, black-owned bank. Among the city’s 14 largest law firms, not a single one of the 167 partners was black. Six–or 2.2%–of the 267 associate partners were black.

Despite “the considerable political changes of the 1970s…Main Street remained a white street,” they concluded.

Nor can black politicians dictate the integration of social institutions. White participation in Richmond public schools, relative to population, appears to be the lowest in the state. In housing, the number of blacks living in the city’s most affluent neighborhoods remains minuscule. Less than 15% of the city’s residents live in integrated neighborhoods, according to the city’s equal opportunity housing agency, HOME.

Unquestionably, however, the Richmond of 1985 is different than the Richmond of 1977. Public schools, reflecting black support, receive a larger share of tax dollars. City boards–from the housing authority to the planning commission–have gone from majority white to majority black membership. Black role models now include the city manager, the fire chief, and several city department heads. “The process has opened up so that all people can participate,” says McDaniel.

At the lower end of the economic spectrum, blacks say that is not enough. “It’s much worser now than 20 years ago,” asserts Curtis Holt, the grass roots organizer and lay preacher who brought the Voting Rights Act litigation that produced Richmond’s ward system. Holt is seated in an armchair in the four-room, public housing unit he shares with his wife, a son and a granddaughter. What Holt sees outside his window makes him long for a gentler day. “The youth comes up useless,” he says. “You have many persons without jobs that need to be on jobs.”

A few miles away, S. Buford Scott sits in a tastefully decorated office in the hub of Richmond’s financial district. A former Chamber of Commerce president, prominent in city politics, Scott has a different view. The Richmond of 1985 is “one of the most exciting cities I know,” he says. “We have moved through a very revolutionary day. Whites have learned that they can live with things that 10 or 15 years ago, they didn’t think they could live with.”

Just the other day, Scott said, in historic Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church, the child of a racially-mixed couple was baptized. As he watched, Scott recalled the story–imprinted in Richmond folklore–of how Robert E. Lee took communion at the church one Sunday after the Civil War. At the invitation, so the story goes, an elderly black man in tattered clothes walked to the altar. As shocked parishioners watched, one white man walked forward to stand beside him. It was Lee.

“I thought, that’s a big change in one church, one city in just over 100 years,” Scott said.

So change that comes painfully slow to the Curtis Holts of Richmond’s black ghetto is dramatic, even startling to others. And in 1985, in Richmond, the question long central to Southern politics remains–by whose timetable will change come?

©1985 Margaret Edds

Margaret Edds, reporter on leave from the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot/Ledger Star, is reporting on Black political power in the South.