TUSKEGEE, Ala.–In 1974, on the day the mayor and the councilmen christened the Tuskegee Industrial Park with flowery speeches and a stone slab marker, Jim Roberts stood in the doorway of his rustic, pine-sheltered grocery and watched. Promises of new industry and jobs and a better life drifted across the highway, and Roberts felt the breeze of change. “At least, I was hoping so,” he recalled. Eleven years and hundreds of thousands of federal dollars later, the marker has been joined by an electrical substation, water hydrants, a high-pressure gas line, an airport landing strip and an industrial-sized hanger–everything, in fact, but industry. Only two tiny firms, both black owned, have set up shop. Combined, they employ just over 50 people. Mostly, the park remains in its natural state, a preserve of wild oats, scrub brush, red-clay dirt and towering pines.

Across the way at Roberts’ grocery, life continues its slow, unfettered pace. Dreams of lathe operators and computer technicians pulling up for gas or a Mello Yellow–maybe even, a week’s groceries–have long since died. Business remains scant. The only shift is that Roberts has given up selling cigarettes, a result of his conversion to the Philadelphia True Church of God.

Prosperity is as elusive as ever.

To some, the tale of the Tuskegee Industrial Park is a metaphor for the unending struggle of life in Alabama’s Black Belt, ten or so counties stretching like a cummerbund across the lower half of the Cotton State. That region, in turn, is twin to portions of the Mississippi Delta, eastern North Carolina, southside Virginia, south-central Georgia, eastern Louisiana and the coastal plains of South Carolina–in all, 82 counties in the seven states–in which blacks equal or outnumber whites. In 61 of those counties, whites still control the governing board. But in 21, including Tuskegee’s Macon County, a combination of constitutional challenges, Voting Rights Act litigation, and sheer numbers have produced a result unheard of just two decades ago: blacks govern.

In the Alabama heartland, Macon County, west of Montgomery, and Lowndes County, just south of the capital, tell in microcosm the story of what happens when blacks win political power in the rural South. Macon County, the home of Tuskegee Institute, has long been a social and cultural haven for blacks. With 27,000 residents, only 16 percent of whom are white, the county is the blackest in the South. Inventors, writers and performers from Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver to Ralph Ellison and Lionel Ritchie have walked its oak-shaded streets. In their wake lies a sense of vibrancy and pride, if not wealth. Lowndes County, by contrast, is grimmer and more remote. Seventy-five percent of its 13,250 residents are black. A collection of dusty hamlets: and snake-filled swamps, the county gave birth in 1965 to the Black Panther Party. Its sparsely-populated acres, both then and now, shelter some of the nation’s vilest poverty.

Despite differences, however, Macon and Lowndes, like other black majority counties, share a history of violent oppression, limited resources and undeveloped skills. Two decades after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 ended a century of disenfranchisement, blacks control every seat on the Macon County commission and school board. They hold four of five seats on each board in Lowndes County. Sheriffs in both counties are black, as are several other local officials. The result is a mixed bag of failure and success.

Gone, today, are the night riders and sheet-draped terrorists of past decades. Their passing, like the simple ability of blacks to hold office, signals a psychological emancipation of tremendous import. But socially and economically, the degree of change might give comfort to segregationists who once plastered the word “Never!” on trees and fence posts across the countryside. Social institutions may be officially desegregated; they are not integrated. Public school classes in both counties are more than 99 percent black. Many residents, both black and white, expect them to stay that way. Indeed, segregated private academies for whites are so institutionalized that Macon County’s all-black governing board recently offered to share some of its profits from a new, state-regulated dog track with the all-white Macon Academy.

“You just put your priorities in order and decide which things you want the most,” said Linda Bargainer, who spends $100 a month to send her son to the Fort Deposit Academy in Lowndes County. Bargainer, who is the county’s tax collector, matter-of-factly asserts that segregated schools will remain a permanent feature of local life. “I think they will,” she said.

Nor are schools the only example of continued segregation. Visitors to Fort Deposit, the largest town in Lowndes County, have two options at lunchtime. They can eat a sandwich in their car, or they can drive several miles to the interstate highway. There are no cafes in town. The reason, explained Mayor Ralph R. Norman, Jr., who is white, is that “folks won’t open one up” in an era in which both blacks and whites must be served. Similarly, the county’s major financial institution, the Fort Deposit Bank, has no black officers or board members.

In fact, in a county only 25 percent white, it has never hired a black person in a non-custodial position. The local cattleman’s association and its ladies’ auxiliary, the Cowbelles, are segregated, as are churches and clubs. “The social life,” said Mayor Norman, “is not integrated at all. If anything, there’s less contact than there used to be.”

“When I was a child,” recalled Norman, a retired insurance salesman who emits a rumpled congeniality, “we’d have black quartets come in and sing at the church. Now, we wouldn’t do that. It’d just cause problems. You’d have some people in the church who wouldn’t like it. There’s a nutrition program here in town. They’re not asked to sit separately, but they do…The federal government changed life here, but they didn’t change it the way they thought they were going to. You can’t change social action by law.”

Economically, Macon and Lowndes Counties are at the opposite poles of progress in Alabama’s Black Belt. The poles, however, are not so far apart. Lowndes is the fifth poorest county in the nation. In 1980, almost half of its residents lived below the national poverty line of $10,178 for a family of four. Median income was $7,493, a figure reflected in the absence of hotels, fast-food franchises or chain stores. In timeless tradition, an estimated half-dozen white families and a few companies own the bulk of the land. The sort of depression-era shanties in James Agee’s “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men” mostly have given way to modest frame dwellings, but extreme poverty still exists on isolated, hard-scrabble plots. The effects of that poverty showed up in 1983, when a stunning 48 percent of the county’s juniors failed the language section of the state competency test. Forty-six percent failed at math.

General Electric, drawn by cheap land and proximity to the Montgomery airport, has had a Lowndes County plant on the drawing board for several years, If it opens as scheduled in 1987, the local economy could receive a desperately-needed boost. But opinions are mixed on how much the county will profit. GE has been granted a twenty-year tax exemption, and most jobs may bypass Lowndes County’s unskilled work force.

Blacks in Macon County are more prosperous. The median income of black families in 1980 was $10,423, the highest in the Black Belt. The square in Tuskegee, the county seat, is bustling. There is a Burger King not far away and a sleekly modern town hall. A small shopping center has just opened on the outskirts of town, and Tuskegee Mayor Johnny Ford said he is swamped with inquiries. “I’ll be meeting today with Pasquale’s and Domino Pizza,” he said, “and we’ve got calls from McDonald’s and Wendy’s and Piggly-Wiggly.”

Xerox or General Dynamics Corp., it is not. Despite some retailing gains, Macon County also bears testament to the limits of black political power. Local residents are unusually well-educated for the rural South. There is an aggressive, internationally-known mayor in the county seat town. And the federal government has contributed an estimated $60 million over the last decade toward improvements in rural housing, water and sewer systems, and other items. The combination has not put Macon County blacks on an equal financial footing with the county’s whites, nor the county on an economic par with most of its majority-white neighbors. While black families were earning $10,423 in 1980, local whites had a median income of $17,500. In every other black-majority Alabama county, the income gap between blacks and whites was even greater.

The failure of the Tuskegee Industrial Park to attract industry is, to many, a symbol of the economic hurdles still facing black-run county governments. Ford estimates that he and other county officials have negotiated with as many as 100 firms in the last decade. Yet the percentage of county residents working in manufacturing jobs in 1980 was the second lowest in the state. Tuskegee Institute and the local Veteran’s Administration Hospital remain, as they have been for generations, the mainstays of the local economy. The major addition is the Victoryland dog track, which opened last year. Ford bristles at suggestions that the industrial park has failed, but he acknowledged: “For something to come to Tuskegee they’ve got to be convinced. You know and I know who owns most of the industry in this country.”

Individual and institutional pressure could, and did, however, revolutionize the political structure in Macon and Lowndes Counties. Two men–Mayor Ford of Tuskegee and Sheriff John Hulett of Lowndes County–reflect the experiences of dozens of black elected officials throughout the South. They also epitomize the differences in the counties they represent.

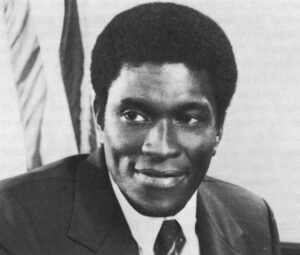

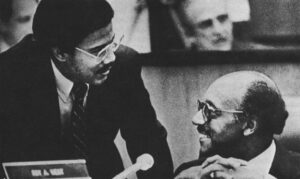

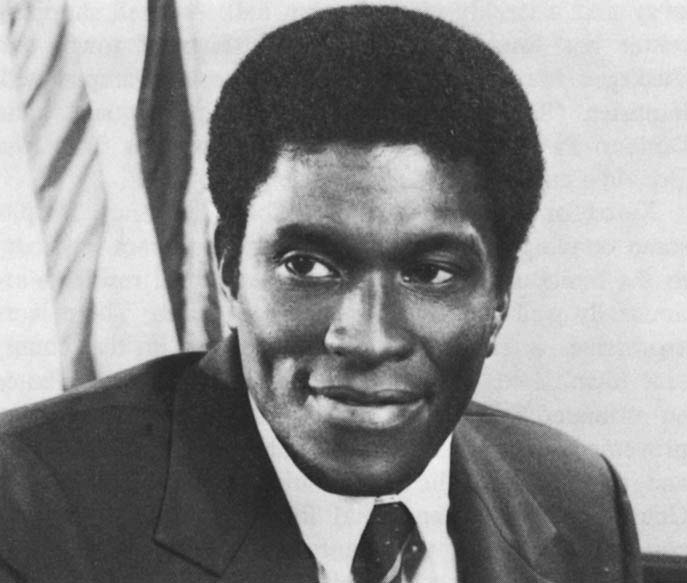

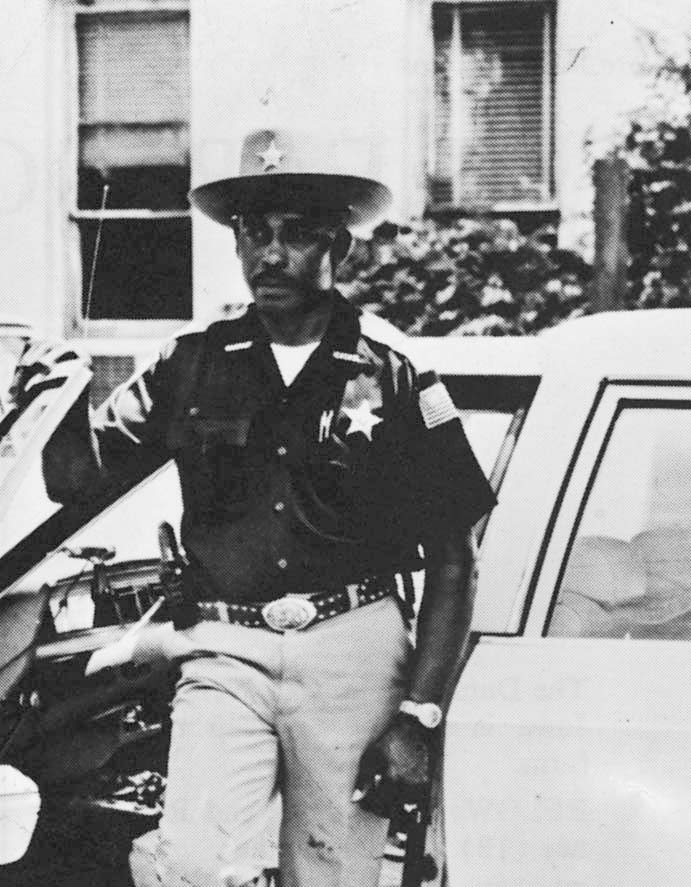

Ford, 42, is suave and articulate. Widely-traveled, he was elected chairman of the World Conference of Mayors in 1984. His office walls are a mosaic of photographs, featuring Presidents and would-be Presidents. Hulett, in contrast, is rough-hewn, uneasier in the spotlight. At 57, he is a legendary figure in the Black Belt. But he dislikes being photographed, and even discourages reporters from sitting in on talks to school children.

Yet, both Ford and Hulett can testify to a remarkable odyssey. Not the least of their bonds is a shared memory of political violence, totally foreign to most Americans. Those memories still shade the surface calm with which both men operate in the 1980s.

Ford grew up on the poor side of Tuskegee, a town where castes divide professional and low-income blacks, as well as blacks and whites. His parents, both of whom did menial labor, instilled a strong work ethic, and deep self-esteem in their only child. In the 1950s, theirs was a town stirred by rising race consciousness. The all-white Tuskegee council, increasingly troubled by the town’s majority-black population, responded by redrawing the city boundaries in 1955. The new lines conveniently excised most blacks. C. T. Gomillion, a professor at Tuskegee Institute, challenged the move in court, and in a landmark 1960 decision–GomiIlion v. Lightfoot–the Supreme Court declared racial gerrymandering unconstitutional.

The episode made an impression on Ford. So did the segregated parks and schools of his youth and the shocking 1966 murder of Sammy Younge, a childhood friend who at his death was trying to use the restroom at the downtown bus station. Ford fled north, worked for awhile in the slums of New York’s Bedford-Stuyvesant section, signed on as a political advisor to Robert Kennedy and–after Kennedy’s death–came home to run for office.

Ford recently described one of the ways in which the Voting Rights Act affected his 1972 election as Tuskegee’s first black mayor. “They had put all the voter registration days in the summer when the students were away,” he said. “There were about 3,700 students. On the last day of registration, the football team, the cheerleaders came back early. We got a bus and loaded up the entire football team, right? Two-hundred-and-fifty-pound tackles. We ran the bus to the courthouse. They just literally scared those little white folks to death. So they just locked the door. They would not register anyone. This was a violation of the Voting Rights Act, so we filed a lawsuit. We took it to the federal district court in Montgomery. The judge ruled in our favor…The voting registrars were ordered to open up again Monday. We registered about 150 students.” The next day, out of 4,000 votes, Ford won by 127.

In Lowndes County, too, opposition to black political power ran deep. It was there in March 1965 that a Detroit housewife named Viola Liuzzo was shot to death on a lonely stretch of highway as she was returning to Montgomery after depositing a group of freedom marchers in Selma. Three Ku Klux Klan members were eventually convicted in federal court of violating Mrs. Luizzo’s civil rights, but the first Klansman to stand trial was acquitted of a murder charge by an all white, Lowndes County jury. So bruising is the memory that–two decades later–P. “Buddy” Woodruff, a white farmer who is now the county’s probate judge and who sat on that jury, still carries a copy of the judge’s instructions in his wallet. The sheet, worn into two pieces and yellowed with age, is Woodruff’s justification for his vote to free the Klansman. “I’ve carried it for twenty years,” said Woodruff. “There were so many questions.’

Within a week of the murder, a young native West Indian, schooled at New York’s selective Bronx High School of Science, was deposited in Lowndes County with a sleeping bag, a few dollars, and a mission to help local blacks–of whom only 250 were registered–realize their constitutional right to vote. That summer, Stokely Carmichael joined with John Hulett, a local construction worker and father of eight, to found the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. The group, which took as its emblem a taut, black panther, later become a model for freedom organizations throughout the Black Belt. Later, too, when the movement had reached west to California, Carmichael and Hulett’s creation was dubbed the Black Panther Party, and it became–with its militancy and outrage–a symbol of fear in a nation torn by the struggle for civil rights.

A small, compact man, his hairline now receding, Hulett sat recently in the sheriff’s office which he has occupied since 1970 and recalled the years of struggle. The black panther, insisted Hulett, was not intended to strike fear. “It was only an emblem,” he said. “We formed a parallel party because when we started filing for office, the Democratic Party upped the fees from $50 to $500. We chose to do our own party so we wouldn’t have to pay the fees.”

But Hulett, who grew up amidst the rural poverty of Lowndes County, was no stranger to repressed fury. And he was determined, along with Carmichael, that–one way or another–change would come. That same summer, a local part-time deputy sheriff shot and killed an Episcopal seminarian and civil rights worker with whom the deputy quarreled one hot evening. And when Carmichael, tense and defiant, pledged at an evening rally, “We’re going to tear this county up, then we’re going to build it back, brick by brick, until it is a fit place for humans to live,” the words could have been Hulett’s.

The day he took office, Hulett met the silent defiance customary when blacks were elected in those years. The former sheriff and his two white deputies simply left. It was up to Hulett to learn the job by trial and error. That he succeeded is confirmed by both blacks and whites. “At first, you didn’t know how it would turn out, whether he would answer the calls of white people,” said Frieda Cross, co-owner of the county newspaper. “Every time anyone called, he answered promptly.”

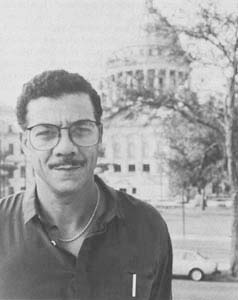

Hulett-Lowndes County’s undisputed political leader is not, however, without critics. And it is growing condition of life in the Black Belt that some of those critics are black. Increasingly, civil rights era leaders are being challenged by younger blacks willing to join political forces with whites. Tax Assessor Elbert Means is the embodiment of that trend in Lowndes County. His targets range from the county’s budget process to its political structure. “I’ve never been called to a budget hearing,” said Means, who was elected in 1978. “The county commission, they have no idea what I do here, and this is 90 percent of their monies. We’re not accountable for nothing. We do what we want to do.”

Means is cooperating, too, with a federal investigation of alleged absentee ballot fraud in the Black Belt. Last fall, Means lost an election to Sheriff Hulett’s son by four votes, but was reinstated by the state Democratic Party due to irregularities in absentee voting. The potential for abuse is confirmed by the county’s swollen voter registration rolls. In a county of 13,250 residents, many of whom are children, there are 12,400 registered voters.

“Nothing has changed in this county that we had a hand in,” complained Means. “We have not had any industry come. The school board is at an ebb. There’s an alarming rate of illiteracy. Kids come here to purchase a car tag. They graduated from high school last year, and they can’t write.”

And so, twenty years after chanting protesters passed through Lowndes County on the historic Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march, life in the Black Belt reflects a curious mixture of disappointment, satisfaction and hope. For some, the very notion that blacks are in positions of authority remains so remarkable that day to day problems pale. “It’s a different world; everything’s better,” said Willie Moore, a retired hospital worker as he pumped gas at a station outside Tuskegee.

Johnny King, who is black and who had difficulty financing the tiny sewing factory he opened last year in the Tuskegee Industrial Park, disagrees. “I don’t see any change,” said King, talking above the whirr of two dozen machines. “You take the white boy. He can go establish himself a line of credit because he grew up in the environment. He played with the bank president’s son, and if they can do it for him, they will. But me, I’ve got to put up by whole life and sign a contract in blood.”

Still others continue to hope that economic and social barriers will crumble as political ones once did. Mrs. Euralee Haynes, who retired this summer as the first black superintendent of schools in Lowndes County, believes that may happen if the General Electric plant finally opens. “GE could come in here and give us the money to make a school of the future,” she suggested.

A day earlier, a white family had enrolled their three children in the public schools, citing the high cost of private academies. Their enrollment boosted to a mere 13 the number of white children among 3,290 students, but Mrs. Haynes was delighted. “Economics can do a whole lot of things. That’s one reason we got three kids back,” she said.

Just as she sees in those three white faces hope that the era of private academies is passing, so Mr. Haynes argues, “GE could change the whole complexity of the system. Who knows?”

And, indeed, who does? These are men and women who in their lifetimes have already seen impossible dreams come true.

©1986 Margaret Edds

Margaret Edds, reporter on leave from the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot/Ledger Star, is reporting on Black political power in the South.