Otis White

- 1983

Fellowship Title:

- How Computers are Changing Work

Fellowship Year:

- 1983

Schooled for Failure

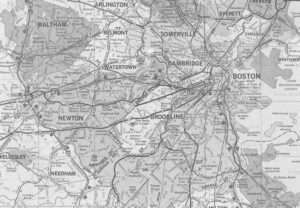

Jim Howell peered through the drizzle at the Massachusetts Turnpike, looking for the exit to Route 128. In the back seat of the blue Malibu, John Weiss was explaining how economic conditions in Boston had improved in recent years. If you looked at Boston from a city planner’s point of view, explained Weiss, who used to be a planner, one of the things you would find most striking is that the number of abandoned stores and houses has dwindled–a sure sign of good economic health. “Ten years ago,” Weiss said, “we had about 5,000 abandoned structures in Boston. Today we have 2,000.” Up in the front seat, Howell, a hulking man with hooded eyes and a thatch of dark curly hair, agreed that the economy of Boston had improved–to the benefit of most Bostonians. But there was another side to Boston, he added, a side of town that the new-found prosperity never visits. “I think there’s a permanent underclass in Boston that’s getting pushed around,” he said. “A white underclass as well as a black

Fear and Loathing in the Electronic Workplace

DETROIT–There is a distinctively carnival atmosphere to manufacturing trade shows, a blend of the bazaar and the bizarre, where managers and engineers can gape at offbeat entertainment and still go back to work the following Monday with enough specifications sheets in their briefcases to impress their bosses. At the AUTOFACT 5 trade show here last November, factory executives could contemplate “total materials handling” with the assistance of a serious young man in a dark suit at the Jervis B. Webb Co. booth. Or they could slip over to the other side of Cobo Hall, to the Digital Equipment Corp. pavilion, where three middle-aged actors in flowing robes were presenting a hammy one-act play. In the Digital play, acted on a flimsy-looking stage before a small crowd of businessmen sitting in plastic chairs, an ancient Egyptian stone-block manufacturer was trying to build a pyramid for the pharaoh. The climax came when the temperamental pharaoh decided suddenly he wanted his monument enlarged from 366 cubits to 444. “But that will put it off schedule,” whined the stone-block

Dark Side of the Chip

Monday, July 26, 1976 is a day printers at the Miami Herald remember the way other people remember the day President Kennedy was shot or the day the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The biggest headline in the paper that morning reported that a cease-fire in Beirut had broken down. But for the 225 or, so linotype operators and compositors, it was not the news, but the newspaper itself that burned July 26, 1976 into their memories. That was the day the newspaper’s managers unplugged the last of the Herald’s linotype machines, cleared the composing room floor of its ancient metal page forms and banks of lead type and began printing the newspaper, from front page to classified ads, by computer. Seldom has a basic industrial change come so swiftly or completely. One day the front page was being set on thundering linotype machines, the metal type so heavy it had to be wheeled about on steel rolling tables, while the noise of the machines and the thick smell of lead mixed freely around the printers.

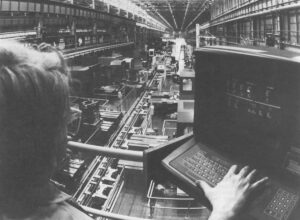

The Electronic Workplace

Out in the northern Kentucky hills, not far from Cincinnati, an eerie minuet of machines strikes up every night on the green slab floor of a factory. It begins late in the evening, during the third shift at Mazak Corp.’s new machine-tool plant in Florence, and it plays until sunrise. During the first shift at the plant, in the morning and early afternoon, two workers watch over a series of giant yellow machining centers, machines that bore a complex pattern of holes into iron castings. So automated is the system that rarely do the men have to touch the machines they direct. When those workers go home, at the start of the second shift, they are replaced by two more. But eight hours later, when the third shift starts at midnight, the dance of the machines begins. The workers line up a shift’s worth of castings for the machining centers, turn out the lights and go home. The machining centers, controlled only by the factory’s computers, bore away in the dark at the five-ton cast-iron