Jim Howell peered through the drizzle at the Massachusetts Turnpike, looking for the exit to Route 128. In the back seat of the blue Malibu, John Weiss was explaining how economic conditions in Boston had improved in recent years. If you looked at Boston from a city planner’s point of view, explained Weiss, who used to be a planner, one of the things you would find most striking is that the number of abandoned stores and houses has dwindled–a sure sign of good economic health. “Ten years ago,” Weiss said, “we had about 5,000 abandoned structures in Boston. Today we have 2,000.”

Up in the front seat, Howell, a hulking man with hooded eyes and a thatch of dark curly hair, agreed that the economy of Boston had improved–to the benefit of most Bostonians. But there was another side to Boston, he added, a side of town that the new-found prosperity never visits. “I think there’s a permanent underclass in Boston that’s getting pushed around,” he said.

“A white underclass as well as a black underclass?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said, “there are some whites in there. It’s not uniquely black. But it is a class that for one reason or another is not able to break the bonds of permanent poverty.”

We were on our way out of downtown Boston on a rainy Saturday morning, headed for Route 128, the nation’s first true high-technology community. Our driver was James M. Howell, senior vice president and chief economist of the First National Bank of Boston and a mover and shaker in the Boston business community.

Giving directions from the back seat was John Weiss, now a private consultant, but for years an aide to former Boston Mayor Kevin White. His specialty then was bolstering old neighborhoods that were declining, usually with a strong dose of federal funds and city tax breaks. Weiss was able to steer us unerringly through the cat’s cradle of roads that tie together Boston’s neighborhoods because as Howell joked, “John built most of those neighborhoods.”

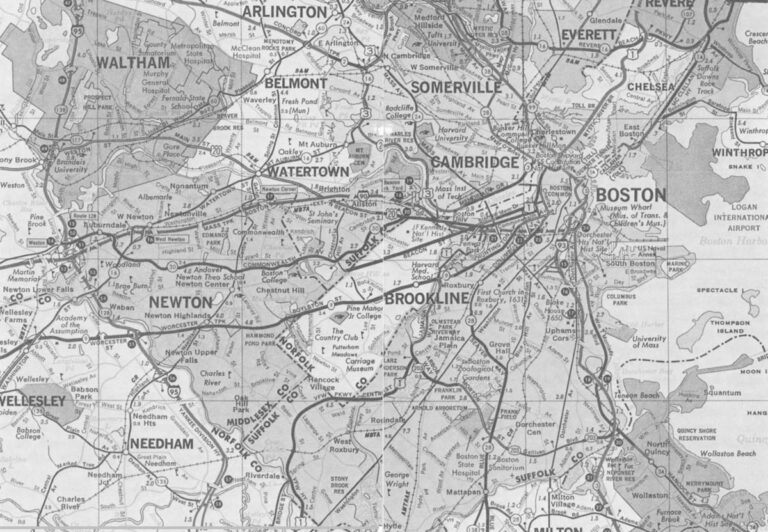

The two men were showing me the physical economy of Boston. The plan was to start at the fabulous high-technology civilization along Route 128, which forms a half-circle around the city. Then we would work our way back toward downtown, loping gently through the affluent city of Newton, through the prosperous, century-old “leafy suburb” of Brookline, across Jamaica Plain, through the grim black ghetto of Roxbury and the insular white ghetto of South Boston, ending up back at the rust-colored Bank of Boston building in the heart of Boston’s gleaming financial district.

The idea was to see how Boston’s new prosperity–a prosperity based on the blossoming of cheap computer power and high-level services–was affecting various parts of the city. What I was to learn was that this new prosperity was a discriminating one. Much of the Boston area is fairly palmy these days with economic success. But there are other parts of Boston, I would see, that are so far removed from the excitement of Route 128 or the affluence of downtown Boston that they may as well have been in Detroit.

Indeed, many observers believe life in Boston’s inner-city neighborhoods has grown even more desperate in recent years. Consider, for instance, the employment situation. The low-skill, moderate-pay jobs that earlier generations of the poor found in Boston’s factories or government agencies are disappearing, replaced by automation or, in a time of tax revolts, simply done without. The manufacturing plants that have sprung up lately are almost exclusively in the suburbs, unreachable by public transit. What is left in the city for the minimally skilled are minimum-pay service jobs.

For those looking to better themselves, then, the route out of the ghetto clearly starts today in the classroom. But in Boston, as in other cities, the public school system–the salvation of future generations–has deteriorated into a cruel joke. A survey last year of Boston teachers and students found that half of the teachers and nearly 40 percent of the students had been victims of crime in the schools in 1982. Four of every 10 students said they feared for their safety during school hours. By the most conservative estimates, fully one-third of all Boston ninth-graders drop out before they graduate from high school, most condemning themselves to poverty.

Boston is hardly unique in having social problems. But what makes its problems significant is that Boston’s economy, a highly evolved mixture of electronics manufacturing in the suburbs and high-level services downtown, is likely to be the shape of things to come elsewhere in America. And Boston’s economy is, inadvertently, making life more difficult for the city’s poor.

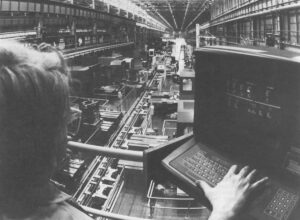

To start with, the city’s labor force is undergoing epochal occupational change, as the computers created out on Route 128 remake factories, offices and stores across the region. Many employees who were vital to commerce a decade ago–keypunch operators, newspaper typesetters, bank tellers, factory operatives and the like–are rapidly being automated out of jobs by cheap computers. At the same time, businesses in Boston are pleading for people with the right type of training, as page after page of Sunday help-wanted ads for computer specialists, technicians and skilled managers attest.

But there is more at work in Boston than employers simply trading one group of employees for another. Computers are changing the very nature of work. The old skills of manual dexterity, physical strength and knowledge of mechanics are increasingly less important in a world where work involves sitting in front of a computer terminal, scanning vast amounts of data. The new basic work skills are more abstract, such as the ability to absorb and understand large amounts of information, or the ability to recognize mathematical relationships and make judgments quickly. Those are not skills that are learned in apprenticeship programs or informally at home. Rather, they are inculcated into students in the classroom.

Many people in Boston have those skills. The city is, after all, within an Ivy League quarterback’s toss of two of America’s most prestigious universities, Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and is home to a score of other colleges and universities. Not only do these universities provide an excellent education for Bostonians, but they draw talented people to the city from around the country. It is also a city where adult education is a big business. At subway stops throughout the city, there are billboards urging commuters to sign up for night school classes at this or that college. Many of the courses are aimed specifically at providing computers skills.

But a large number of Bostonians don’t have the new basic skills and are unlikely to learn them at night school because their public school education was so poor. And without these school-learned skills, they are locked into either declining occupations or the lowest-paid service sector jobs, with little chance of advancement.

Indeed, perhaps even more than race or income, education is becoming the factor that divides the haves from the have-nots. A recent report of the Association of American Colleges discovered there was a “widening gap in skills development” between the best educated people in America and the least educated. Looking at statistics on adult education, the report found that the people most likely to enroll in continuing education courses were those who had previously attended graduate school. As the level of previous education declined, the participation rate in adult education dropped apace.

The education gap explains, in large part, the uneven nature of Boston’s economic blessings. In an economy that thrives by harnessing educated minds, the undereducated get left behind. And in Boston, as elsewhere, the undereducated tend to be the poor and minorities.

The education gap has not yet shown itself in the family income statistics of Boston, and it may take a while to do so, in part because of the peculiar makeup of Boston neighborhoods. As Howell pointed out, at the outset of our tour of the city, “This is a city of European neighborhoods, where the family group has always been very, very tight–maybe tighter than anywhere else in the United States, outside of some neighborhoods in New York. Here you have people who lived together to pool their income. They lived in triple-decker houses, where they had the grandmother on Social Security, they had two or three people in the family working, they had another on welfare and another one in the unemployment line. That kind of arrangement was commonplace here, but it is statistically hard to quantify.” Over three centuries, he added, industries have come and gone in Boston, wages have risen and fallen, “and yet people are able to make up for it because they’ve been making up for it for years.”

Boston is indeed a master at adapting to change. It is a long-distance runner of a town, shaped by adversity, as lean and hungry as the men and women who arrive there every April to run in its famous marathon race. Its economic history could serve as a working model of what Soviet economist Nikolai D. Kondratieff called the “long wave” theory of economic development–that in a capitalist society, the economy advances in 50-year cycles.

Kondratieff’s theory has been hotly debated in economic circles from the moment Kondratieff formulated it in 1922, but Bostonians would have little trouble accepting it. Since their city’s founding, they’ve swum an ocean of long economic waves, as farming came and went, followed by clipper ships, textiles, machine-tools, shoemaking, watchmaking and armaments.

Today Boston is riding the crest of yet another wave of innovation, the development of tiny cheap computers. Many of the companies that are leading the nation in developing cheap computer power began in dimly lit garages around Cambridge’s Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Later, in search of larger quarters and cheaper rent, the computer companies drifted out to Route 128, where pig farms were being subdivided into campus-style industrial parks. These companies’ products–minicomputers, desktop computers, electronic automation devices–are sweeping today through offices and factories across the country, pouring their profits back into the Boston economy.

At the same time, Boston’s sophisticated service economy–the banks and insurance companies and consulting firms that crowd into the downtown areas, plus the city’s cadre of prestigious hospitals and schools–has caught fire. The success of the service companies can be read in their numbers. As Weiss points out, “We have more consultants per square inch in Boston than anyplace else in the United States.”

But within this picture of prosperity, there are some important pieces missing, It is clear, for instance, that most of the jobs that have been generated inside Boston in recent years have gone to suburbanites, not inner-city residents. Today, well over half the jobs in Boston are held by people who do not live there. A look at the kinds of jobs being created may explain why. A third of all Boston jobs today are professional, managerial or technical, requiring a college education or equivalent technical training. Another 28 percent are clerical jobs, requiring at least a solid high-school education, something Boston public schools have often failed to deliver. The balance of the jobs are in sales and service or maintenance and production work.

It is also clear that blacks and other minorities are not participating at almost any level in the city’s economic bounty. The Boston office of the federal Equal Employment Opportunities Commission issued a scathing report last winter that said blacks had been cut out of jobs in the Boston area from the top to the bottom–from the executive ranks of high-tech companies to the janitorial staffs of downtown office buildings.

Rather than making steady progress, minority employment was actually headed the other way in a number of key Boston industries, the EEOC found. The percentage of minority employees actually declined between 1970 and 1982 in such businesses as securities brokerages, printing and publishing companies, communications concerns and investment companies. Blacks and Hispanics make up barely 1 percent of all executives in electronics companies, and just 2.5 percent of all office, clerical and sales workers–the bulk of the downtown work force. Boston’s labor force is 29 percent black or Hispanic. Across the entire metropolitan area, minorities make up 8 percent of the work force.

The reasons given for the paucity of black executives and office workers are many: lower educational levels (although Boston’s black population tends to be better educated than blacks elsewhere), limited access to new jobs in the suburbs, lack of knowledge of job opportunities, competition from other ethnic groups, including a wave of Asian immigrants in recent years, and so on. And there is something else. “This is the most racist city in America,” one white Boston executive admitted.

Whatever the reasons, the growing isolation of blacks in Boston is a dark cloud behind the city’s silver lining, and it bears an ominous message for other cities following the Boston economic model. When The Boston Globe set out last year to examine the living conditions of blacks in Boston, it did so by comparing the lives of blacks there to lives of blacks in six other cities-Atlanta, Houston, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Miami. The Globe’s conclusion was that there was only one city among the six where blacks fared as poorly as they did in Boston. That other city was Miami, which has suffered two race riots since 1980.

Mean Streets

From Route 128, we drove through Boston’s well-appointed suburbs past a country club so old it is named simply The Country Club, along the more marginal sections of Jamaica Plain and into the mean streets of Roxbury, the city’s principal black ghetto. The success of other parts of Boston is so alien in Roxbury, Howell said as we drove past Dudley Square, the commercial center of the community, that any display of success there can be dangerous. Just in the past few years, he said, two businessmen whose Roxbury businesses had been financed by the First National Bank of Boston had been killed there. As a result, he went on, his bank is inclined to finance only those businesses, like light manufacturing, that can operate anonymously in inner-city neighborhoods.

From Roxbury, we toured the city’s South End neighborhoods, near the Prudential Center, then crossed under the Southeast Expressway and emerged on West Washington Street, which leads to South Boston, the city’s tough white ethnic community. As we were coming into South Boston, I asked Weiss how poor the area was. “Poor,” he said. “Sections of South Boston are equivalent to sections of Roxbury.”

The section of South Boston most familiar to people outside Boston is the street in front of South Boston High School, where in 1974 hundreds of Southies, as the community’s residents are called, stood to jeer black students as they arrived in school buses. At the height of the troubles, there were more guards per pupil at South Boston High, trying to keep order, than there were guards per inmate at Walpole State Prison, the state’s maximum-security penitentiary.

Busing Crisis

During the busing crisis, which dominated the school system’s attention for years, education in the 350-year-old Boston Public School System ceased, for all intents and purposes. A good day, school officials recalled, was measured then by how much order was kept in the classrooms, not by how much was taught.

But the busing crisis was not the sole cause of the breakdown of education in Boston. Corruption and incompetence had been widespread among the higher-ups of the school system for so long that one present-day school official said recently, “If you ask me what was the purpose of the school system (in the 1970s), I’d say it was more an employment agency for adults. That was its chief purpose. Secondarily, it was an education system.”

If so, education was a poor second indeed. Superintendent Robert R. Spillane, the new, reform-minded head of Boston schools, described the situation he inherited: “When I came here in 1981, 30 percent of the total high school population was reading below the 20th percentile. Translated, that means they couldn’t read at the level of the prose used in any of the textbooks used in high school. And we wondered why they were dropping out and fighting.” The new school administration also wondered how many were dropping out, since record-keeping at school headquarters was so shoddy, there was no accurate count of high-school dropouts. (Even today, the administration must estimate the percentage of students who never make it to graduation. The best guess: between 33 percent and 47 percent.)

Even for those who stayed on to graduate, there was no guarantee of an education. Asked if he thought there have been graduates of Boston high schools who could not read or write, Spillane says bluntly, “I don’t think–I know there have been.”

The economic and social consequences of such neglect aren’t hard to guess. Boston school graduates, diplomas in hand, couldn’t find meaningful work in their own hometown because employers were shocked by what they had seen and heard of the local schools. And as disappointed graduates labored at menial jobs, they could see suburban commuters streaming into the city every morning to take the positions they were denied.

This might have continued indefinitely, except that by the late 1970s, the quality of graduates of the suburban schools had also deteriorated. Suddenly businesses couldn’t find competent workers anywhere. “I use the statistic,” says Howell, “and nobody in our personnel department at the bank has disagreed with it yet, that two-thirds of all the people who come in to apply for entry-level positions at the bank can’t complete the application form.”

By the time Spillane took over as superintendent, then, both the school system and the business community were ready for basic change. The result: a remarkable agreement called the Boston Compact was signed. Under the Compact, the school system agreed to reform itself–to raise its students’ scores on standardized tests, to improve attendance, to lessen the dropout rate. The city’s leading businesses, in turn, agreed to hire a minimum number of Boston school graduates every year, eventually up to 1,000 a year. (That is not a particularly great feat. The Boston economy absorbs 30,000 job applicants a year.)

The fact that the Boston Public School System needed to be jump-started by such an agreement indicates the extent of the system’s decline. But if the Boston schools’ deterioration was different from that of large school systems anywhere else, it may be one of degrees. In the past three years, half a dozen national reports and maybe a score of state reports have indicted schools for not teaching children what they need to know in a computer-oriented world.

The most important of the studies–and one of the harshest in its criticism–was the report of the National Commission on Excellence in Education, which warned that America’s economic foundations were being threatened by a “rising tide of mediocrity” in the schools. Among other things, the commission reported that 13 percent of all 17-year-olds, one of every eight, were functionally illiterate.

Those finding come as no surprise to corporate personnel officers. An industry-supported research group surveyed executives of 184 companies two years ago about the quality of their employees’ education. Its startling findings were that 40 percent believed their secretaries had difficulty reading well enough to understand the general flow of correspondence that passed through the company, half said their managers and supervisors could not write a grammatically correct paragraph, and half believed their skilled and semi-skilled office workers, like bookkeepers, could not handle decimals and fractions.

If there is a ray of hope in the general gloom that has settled over education today, it is that nearly everyone seems to have awakened to the education gap, including the most important group, youngsters themselves. I went by one inner-city Boston high school on a snowy Monday last January to talk with students about education.

Jeremiah E. Burke High School is in a tough section of North Dorchester, a few blocks south of Roxbury. The Burke, as it is called, was itself such a tough place a few years ago that when its new principal took over two years ago, he found that muggers were coming into the school from outside and robbing teachers and students. The new principal, Albert Holland, put guards at the school’s entrances to keep away the outside troublemakers, while he began ridding the school of its inside troublemakers, expelling those students who were sources of constant disruption.

The day I was there, the Burke was peaceful and orderly. Holland, 38, a handsome, soft-spoken black man, introduced me to five of his students. The students’ ambitions ran an interesting gamut, from one who planned to study business administration in college with an eye toward starting his own business one day, to another who wanted to join the Marines and learn computer programming there, to the plans of Dawn Hines, a pretty, slight l0th grader, who wanted to be an interior decorator because she had once seen a Doris Day movie about an interior decorator. Through the decades, the racial differences and the income levels, Doris Day had left an impression with a teenager in Roxbury.

One of the students, Nathaniel Mitchell, a senior, said he wanted to go to college to learn electrical engineering. A tall, gangly youth who was born in the Dominican Republic, Nathaniel said he worked part-time at a restaurant after school. When I asked him what kind of work his parents did, he seemed embarrassed and said quietly that he lived with his grandmother, who was on welfare.

I asked the five if any of them had ever considered dropping out of school. There was a chorus of “no” and “no way” from the group. Then I asked them if they knew what happened to their classmates who dropped out. Nathaniel spoke the loudest. “They’re in the street,” he said grimly. The others nodded.

©1984 Otis White

Otis White, on leave from Florida Trend magazine, completes his investigation of how computers are changing work.