DETROIT–There is a distinctively carnival atmosphere to manufacturing trade shows, a blend of the bazaar and the bizarre, where managers and engineers can gape at offbeat entertainment and still go back to work the following Monday with enough specifications sheets in their briefcases to impress their bosses. At the AUTOFACT 5 trade show here last November, factory executives could contemplate “total materials handling” with the assistance of a serious young man in a dark suit at the Jervis B. Webb Co. booth. Or they could slip over to the other side of Cobo Hall, to the Digital Equipment Corp. pavilion, where three middle-aged actors in flowing robes were presenting a hammy one-act play.

In the Digital play, acted on a flimsy-looking stage before a small crowd of businessmen sitting in plastic chairs, an ancient Egyptian stone-block manufacturer was trying to build a pyramid for the pharaoh. The climax came when the temperamental pharaoh decided suddenly he wanted his monument enlarged from 366 cubits to 444.

“But that will put it off schedule,” whined the stone-block maker, his hands flailing the air.

“Pharaohs wait for no man,” the pharaoh’s messenger replied coldly.

“Fine,” said the first actor, now hysterical. “I’ll just catapult the blocks across the river. And then you’ll have me dream up a little something that will toss them onto place.”

“Grab hold of yourself,” the block maker’s partner said. “Someday, people will appreciate what we’ve done.”

“No, no,” cried the disconsolate man. “They’ll remember the construction company. They’ll remember the pharaoh. But they will not remember the block manufacturer–believe me.”

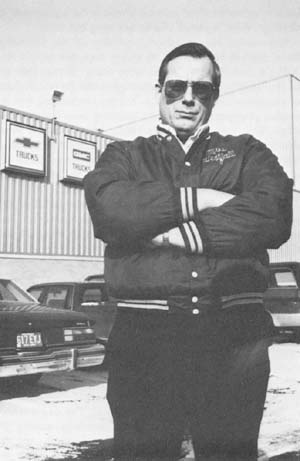

Out in the audience, middle-level managers in earth-tone sports jackets chuckled appreciatively and nodded. But over on the side, a large man in a brown leather jacket and blue striped tie merely stared at the actors as the music welled up and a commercial for Digital automation equipment began. “Come on, let’s go,” he said to his companion, a dark-haired man in a navy blue overcoat.

If Mike Westfall, the man in the leather jacket, didn’t have much sympathy for the daily pressures of factory executives, ancient or modern, it wasn’t too surprising. Westfall is a United Auto Workers (UAW) union member who drives a truck in the cavernous Chevrolet truck plant in Flint, Mich., and as he sees it, executives don’t have much sympathy for him, either.

By the time he walked into Cobo Hall that morning, he had already put in a full, pre-dawn shift at the plant, slipped on a tie and, with a friend, Bob Evans, driven 57 miles to Detroit to view the trade show, where the latest in computer-controlled factory automation equipment was on display. Unlike the hundreds of managers and engineers tramping about the blue carpet of Cobo Hall, Westfall wasn’t there to buy anything–not a robot, nor a computer design system, nor even an electronically controlled machine tool.

He was there to spy–although Westfall never personally uses that term. “I just call it attending trade shows,” he said with a shrug.

Like most spies, Mike Westfall believes deeply in a cause. His cause is to convince unions and companies they should change the way electronics is entering the American workplace–the kinds of electronics that were on display that day in Detroit. If the gathering storm of computer automation isn’t diverted, he believes it will destroy much of what he associates fondly with Industrial America: good-paying factory jobs, assertive labor unions and prosperous auto towns like Flint, where he works.

“We aren’t saying we’re going to stop automation,” Westfall said, speaking for himself and a small band of UAW activists who share his fear of the electronic work place. “We’re not going to stop it. It is a force of nature, and it’s not going to be stopped. What we’re saying is, do these things, but do them with social responsibility, so that the victimization is minimized and so our communities don’t suffer.”

Westfall has been preaching his sermon on the looming dangers of computer automation for better than three years, since, almost by accident, he began looking at the robots and other electronic devices that were finding their way into auto plants. That initial, almost casual interest became an obsession later on.

To help spread his message, he mails a monthly newsletter about technology to UAW officials and others who are interested in the subject (in his occasionally vitriolic newsletter, he referred to the auto companies once as “pirates of the high seas”). He has appeared several times on local television public-affairs shows. Inside his own plant, he hands out literature about automation to his co-workers as he drives his truck to and from the assembly line. Sometimes, he simply passes out brochures from robotics companies–brochures he picks up at trade shows like AUTOFACT 5–after first stapling a piece of paper to the top that says: “Read and pass on.”

But for all those efforts, Westfall’s campaign has made little impact on the UAW hierarchy, in either Flint or Detroit. At UAW Local 659 in Flint, President Bob Breece said he was as gloomy as Westfall about the ultimate effects of computer automation on the UAW and on Flint. Still, says Breece, “You can’t stop it. They own the business,” he says, nodding his head in the direction of the Chevrolet plant across the street. “And I tell you what, if I owned the business and I found a way to fatten my billfold a little more, I’d do it too.”

On the other side of town, at a union hall in the shadows of the giant Buick complex, Local 599 President Al Christner said that, over the years, automation has taken a toll on his local’s membership rolls. Even so, he is glad his members aren’t paying too much attention to Westfall’s efforts to stir them against GM’s program of automation. In the auto industry these days, Christner explains, every General Motors plant is competing against every other GM plant for work. Too much labor strife, he says, and GM shifts the work elsewhere–a situation that, as a labor leader, puts him in a delicate situation.

Says Christner, “I don’t want to give GM the impression we’re against robots.”

Across America, union leaders find themselves in a similar delicate situation as they face the advent of the electronic workplace. Since the 1960s, when unions were at their peak of power and influence, labor’s strength has ebbed drastically.

The reason is as plain as the Toyota in your driveway. Foreign labor has underbid most of the unionized, and some of the non-unionized, sectors of the American economy. Sometimes that foreign labor bas been employed by foreign companies, like Toyota, and sometimes it works for American-owned companies, like General Motors, which has opened plants around the world, some of which ship low-cost components back to the U.S. In either case, the result has been that the market for American-made goods–cars, steel and rubber–has leveled off or declined.

That situation alone would be enough to keep labor leaders thrashing in their sleep. But what makes labor’s situation even more delicate is that Corporate America’s remedy for foreign competition–massive computer automation–is nearly as painful as the malady.

Consider the case of General Motors’ Delco Electronics Division. Because of rising U.S. labor costs, Delco began 10 years ago making car radios in Singapore and Mexico, abandoning its American plants. Last year, Delco announced it was bringing its radio facilities back to the U.S. Why? Because car radios today are nearly totally electronic, meaning they require little assembly work now. And what assembly work there is has been thoroughly automated by Delco.

As a result, when Delco reaches full production in four years, it will need only 1,200 workers, including clerical and management help, to turn out its American-made radios. While even that small addition to the work force might make UAW leaders happy, their joy will likely fade if they consider that Delco would have needed better than twice that number of workers had it brought the old, hand-assembly system of production back to the United States.

More With Less

Similar feats of automation are being performed elsewhere in the industry. In fact, Chase Econometrics estimates that up to 25,500 industrial robots and thousands of other computer-driven equipment will be at work in the auto industry by the 1990s. When all that electronic gear is in place, the forecasting group adds, the automakers will be able to build the same number of cars then as they do today–with 20 percent fewer workers.

And labor’s problems don’t end with the auto industry. From airline workers to machinists to newspaper printers, unions are in retreat, granting contract concessions that could not have been imagined 10 years ago. Today, just slightly over 20 percent of the work force is represented by a labor union. In 1945 union membership comprised 35.8 percent. And the end of that decline is not in sight. In 1950, unions won three-quarters of all the federally supervised representational elections they entered. Today, they win less than 45 percent. In the biggest sector of the labor force–white-collar and clerical workers–unions are hardly more than ciphers.

Those are trends that have been decades in the making. What is new-and truly scary for union leaders is that, in many industries, unions are facing actual declines in their membership. The backsliding is not due entirely to automation; typically, it is a result of advancing technology in combination with some other factor–deregulation, added competition or, simply, changing demand for the industry’s products. Deregulation, say, puts a premium on a company holding its employment to a minimum, and the new, computer-driven technology gives the company the means by which to eliminate the unneeded workers.

So what’s a labor leader to do? The traditional labor stance has been to welcome automation, as long as wages are kept in pace with productivity gains. Explains Glenn E. Watts, president of the Communications Workers of America (CWA), which represents telephone workers, among others: “Right up front, for almost the entire history of our union, back some 40 years to 1938, we have said we welcome automation, but…and we put the but in all caps, quotes and with an exclamation point. We welcome automation if the increased productivity and its resulting profit are shared with the workers who are involved in the process.”

That is fine as long as both the industry and the union are growing, as the telecommunications industry and the CWA are. But what happens to the union’s attitude toward automation if it actually means fewer jobs?

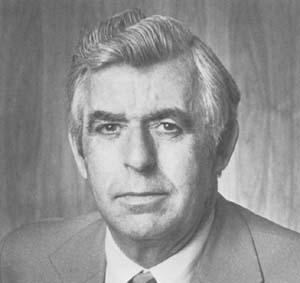

That has happened to the past to some unions–the United Mine Workers, to name one–and it is happening now to others. The United Auto Workers, for instance, had 1.5 million members in 1979, when the industry was near its peak sales of 9.3 million cars a year. Today, the auto companies are selling fewer than seven million cars, and the UAW’s membership has dwindled to 1.1 million. Since no one expects the car companies to sell nine million cars a year before 1990, if then, any further improvements in the industry’s productivity will come at the expense of its workers–a debilitating situation the UAW has never before been faced with. Donald F. Ephlin, vice president of the UAW and director of its huge General Motors Department, acknowledges his union’s dilemma: “The situation today is that increases in automation directly affect reductions in the (industry’s) work force.”

The dwindling unions of the past ultimately accepted automation, even when it brought reductions in their own ranks. Their reasoning was that, without productivity improvements, entire industries were likely to die, and it was better to lose some jobs than all of them. The dwindling unions of today will probably reason the same way. Indeed, the UAW’s position is clear, says Ephlin: “We’re in favor of new technology and productivity increases.”

Coping with membership loss in the declining industries is not labor’s only trouble, though. Electronics is bringing a much bigger problem for unions. Cheap computer power, which is the basis of this latest wave of automation, has only begun to change the industrial structure of America. Before it is done, possibly early in the next century, it will have created vast new industries, destroyed some old ones, and changed most of the rest. Unions gathered their greatest strength during periods of stability. What is ahead will be anything but that.

One early, but prominent, casualty of the Industrial Revolution being wrought by cheap computer power was AT&T’s Bell System. There were many factors that led to the breakup of the Bell monopoly–the largest division of corporate assets in history–but the central one was the sudden competition for Bell’s lucrative long-distance services. That competition was hardly possible a few years ago because the cost of communications equipment was so high that competing with the Bell system was prohibitively expensive–in other words, nobody but the phone company could afford to be in the phone business.

What happened was the cost of electronics fell so fast over the past decade that the economic barriers to entering the long-distance market just melted away. By the time of the Bell breakup, hundreds of tiny companies had jumped into the business, each one willing–and able–to undercut Bell’s prices.

Over the past 50 years, the Communications Workers of America had thoroughly organized the Bell system and the much smaller independent telephone companies. But the CWA has been unsuccessful in the past few years in organizing Bell’s mushrooming competition. And, unfortunately for the union, that is where the growth in the telecommunications industry is likely to be for the foreseeable future–with the small companies.

And it isn’t just the CWA’s problem. The steelworkers’ union has been unable to make headway among the growing, prosperous mini-mill steel operations, and the various airline unions haven’t been able to crack the burgeoning low-fare airlines that are giving the big, unionized carriers so many headaches. As the price of computer technology continues to drop, and the barriers to competition drop with it, unions can expect many more problems trying to keep their grip on the industries they’ve already organized.

There are other problems ahead for Big Labor. One is that unions simply haven’t kept up with the changing patterns of work, a rather basic requirement if labor organizations wish to remain as meaningful institutions. One major reason is because Big Labor is still under the sway of its 50-year fixation with industrial work. Most work isn’t performed today on factory floors; it is carried out in offices and stores, and the quickening pace of factory automation will keep pushing people into offices. Yet organized labor has been singularly unsuccessful in organizing white-collar workers.

Most labor leaders have little feeling for the frustrations of office work. By and large, they come from the mostly male world of the shop floor, where the needs are simple: more money, better pensions, shorter working hours. Hourly office workers, most of whom are women, have an entirely different set of concerns, which center around things like a need to gain respect for their work, greater opportunities for advancement and comparable pay for women. Those are issues that seem alien to the plant-mentality of the AFL-CIO.

Indeed, one UAW official said recently he was dubious that office workers would ever be organized. The reason: Office workers, to his way of thinking, didn’t need a union as factory workers did. He offered as an example his secretary. “Nobody yells at her like they do in a plant,” he said. “The work is clean, and nobody treats her badly or abuses her.” As long as union leaders have that kind of condescending view of office work, they are likely to make few converts.

If organized labor does make any inroads into the ranks of office workers, it will probably be with organizing methods similar to those used by District 925 of the Service Employees International Union. Borrowing a page from the women’s movement of the early 1970s, the Cleveland-based organization uses female organizers whose first job is often to raise the consciousness of office workers. Says President Karen Nussbaum, a former clerical worker herself: “You have to organize people with people like themselves. That has to be at the very beginning. And you have to understand what are the (workers’) concerns and respect them.” So far, District 925 has only 5,000 members, but its tactics have been good enough to win 15 of its last 16 representational elections.

Almost any way labor turns, it faces a long period of wandering in the wilderness. Even if it should adjust to the turbulence of the electronic Industrial Revolution and attune itself to the era of the white-collar worker, it will come at a great cost to the old-line unions, like the United Auto Workers.

Mike Westfall, the self-appointed UAW point man on automation, believes it doesn’t have to be that way. He is convinced companies can have their automation and still create more union jobs. If that isn’t happening, he says, that’s because corporations are using computer-based automation as an excuse to weaken the unions.

It was to prove that point that Westfall drove from Flint to the AUTOFACT 5 trade show in Detroit–to look over the latest in electronic labor-saving gadgetry and, perhaps, to gather some material for his next newsletter. Inside Cobo Hall, he and his friend, Bob Evans, wandered among the exhibits for factory software and industrial robots and electronic inventory systems. He chatted knowledgeably with the salesmen, discussing the finer technical points of the machines, as he took mental note of how many workers each machine could displace. At nearly every booth, he gathered a handful of printed material, explaining with a smile to the salesmen that he was taking some brochures back to his “colleagues.”

On his green and white AUTOFACT name badge, which everyone attending the show was required to wear, it read: “Mike Westfall, Materials Specialist, General Motors.” It also gave an address in Chesaning, Mich., where he lives. What Westfall actually does for a living is deliver parts to the Chevy truck plant’s assembly line; hence, by his lights, he is a “materials specialist.” If the salesmen, who scrutinized carefully his name badge before they talked with him, chose to interpret anything else from that vague-sounding title, he said, arching his eyebrows, that was their problem. “I never lied,” he said.

Before long, though, Westfall was bored. There wasn’t much new at this trade show, he sniffed. He had seen much of this stuff, and some that was even more advanced, at other robotics shows. After a couple of hours of wandering around the convention hall, he was headed for the door, when he stopped by one last booth, this one for a software company.

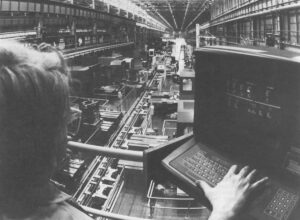

A well-groomed young man with brown-framed eyeglasses and a neatly tailored gray suit stepped up and, eyeing Westfall’s name badge, offered to show him some of the features of his company’s factory software. By using his company’s system, the young man said, running through his spiel professionally, a manager could keep tabs on every machine in his factory. He punched a few keys, and up on the computer screen a row of numbers appeared–a report on a fictitious group of metal-cutting machines.

“I’m giving you my reject counts and the net pieces,” he said, pointing to a couple of numbers. He pointed to another group of two numbers. “It also tells me I’ve got, let’s see, one…two…three bad machines.”

“So, actually, you could monitor individual workers, as well,” Westfall asked, innocently.

“Oh, absolutely,” the salesman said. “I could do this”–he punched some more keys–”and here I can see what this machine–machine number 11–is doing. You see here’s the job at hand, here’s what my third shift gave me, here’s what my previous first shift gave me, and my second shift. I could look at that and say, why did my first shift give me only 195 pieces? Is the operator at fault?”

The salesman stepped away from the machine and glanced at Westfall, who nodded, as if impressed. “Or look at this,” the young man said, after a moment. He stepped back to the terminal and began punching in more information. “If you think that was impressive, wait until you see the rest of it.”

As the salesman bent down over the computer screen, Westfall looked over the salesman’s shoulder at Bob Evans, smiled knowingly and winked.

©1984 Otis White

Otis White, reporter on leave from Florida Trend magazine, is investigating how computers are changing work.