Samuel Dillon

- 1989

Fellowship Title:

- Nicaragua's Contra War

Fellowship Year:

- 1989

A Contra Rampage–With Blessings from the United States

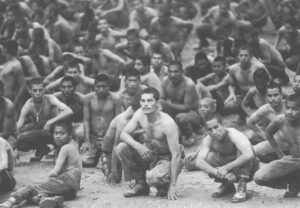

The October 1983 attack by U.S.-financed contra rebels on the northern Nicaraguan town of Pantasma was, militarily, a brilliant surprise strike, a classic town takeover, one of the few that the rebel forces ever achieved. It was also one of the single most destructive contra rampages in the entire seven-year war. Rebel troops razed an army garrison, police station, bank, sawmill, grain elevators, and a dozen government offices, burning several teachers alive in a rocket attack and executing prisoners before a massed crowd. The Sandinista government called the attack a “massacre” and an “atrocity.” Busing hundreds of international visitors up from Managua to tour the town over the following years, government tour guides turned Pantasma into a premiere example of plunder and havoc that remained a symbol for the rest of the conflict. Contra propagandists and the Americans financing and administering the rebel army, however, saw things differently. They saw Pantasma as a virtuoso performance. Contra soldiers training in the Honduras. (Photo by Jason Bleibtrew/Sygma) The commander who led the attack was former Nicaraguan National

The Contras Murdering Their Own: A Grisly Retribution

In 1983, leaders of the CIA-financed Nicaraguan contra army ordered the detention of four field officers accused of insubordination, graft and murder. Argentine and Honduran military officers interrogated the detained, and then the rebel general staff ordered them executed. With dozens of rebel fighters looking on, the men were strangled to death and their bodies burned and buried in a clandestine Honduran gravesite. Rebel officials acknowledged the killings at the time, portraying them as military executions rather than as common murder and suggesting that they demonstrated rebel commitment to principles of law and the norms of military justice. A CIA agent working with the contras also acknowledged the executions, saying they followed a “court-martial” of the accused rebel officers. But details of how the men died have never been known publicly. Now rebel witnesses have for the first time provided a careful account of the execution, an important early glimpse into what U.S. and rebel officials considered acceptable military punishment within the CIA-financed movement. The details suggest that the forms and procedures used in the

Rebellion Among The Rebels

When several angry Nicaraguan contra field commanders last year challenged Enrique Bermudez, the rebel army’s “Supreme Commander,” their first tactical move reflected the dynamics of power within the anti-Sandinista movement: they called the U.S. Embassy in Tegucigalpa to request a meeting with the CIA station chief. Several days later, Diogenes “Fernando” Hernandez, one of the dissident rebel officers, got a phone call at his rented home in the Tegucigalpa capital. It was a CIA official known as “Terry,” a dark-haired American of about 40 with a good command of Spanish whom Fernando had met a few times when the agent had helicoptered into the rebels’ border base camps. The American at first insisted on a one-on-one meeting with Fernando. But later he agreed to a group encounter. The contra’s largest training center-in the mountains near Yamales, Honduras. (Photo by Jason Bleibtreau/Sygma) The meeting came days later, one afternoon in April 1988, at the home of a U.S. Embassy political officer. With Fernando were two other rebel commanders leading the challenge to Bermudez, Walter ‘Tono” Calderon,

The Ambush of A Young Sandinista: An Early Contra Victory

The death of Daniel Teller in a 1983 contra ambush deeply shook colleagues throughout the Sandinista Front. He’d proven himself to be one of Nicaragua’s most brilliant and promising young political cadres. During four years of revolutionary work in northern Jinotega province, Teller led the transformation of the Sandinistas’ guerrilla columns into regular army battalions, forged a Marxist strategy for backwoods class struggle, and pioneered the Revolution’s political approach to counterinsurgency war. Teller’s work was meticulous, and despite his own middle-class origins, he sought to develop friendly bonds with Jinotega’s farmers. But the revolution’s collectivization and agrarian transformation policies infuriated many northern hill people, and Teller’s career unfolded against the ominous backdrop of peasant rebellion. By 1982, dozens of CIA agents across the northern border in Honduras were working hard themselves to train and arm a counterrevolutionary army. Their efforts bore fruit, and in May 1983, a 160-man contra task force, newly-armed with U.S. weapons and operating under the command of a former National Guardsman schooled at West Point, marched down from a mountain redoubt