William Serrin

- 1978

Fellowship Title:

- Farmers, Food and Farming

Fellowship Year:

- 1978

We Are What We Eat: The Price of Food and the Reasons Why

“I’m tired,” a depressed-looking, middle-aged woman, pushing a shopping basket loaded with groceries through a Farmer Jack supermarket in a Middle West city, said one day not long ago. “The price of food makes me tired.” It should. A one-half gallon carton of white milk, 93 cents. A 12-ounce container of frozen orange juice, 83 cents. A 12-ounce package of Peschke’s bacon, $1.28. A pound of Land 0 Lakes butter, $1.55. A one and twelve-hundredths pound package of hamburger, $1.43. A can of Chicken of the Sea tuna fish, $1.44. A two-pound can of Maxwell House Coffee, $5.58. Food prices have soared in the past years-70 percent in the last ten years, 10.5 percent in 1978, an expected 6 to 11 percent in 1979. Always trying to put the best face on things, the U.S. Department of Agriculture says that Americans spend little on food, compared to other nations. Moreover, America, the department says, is the best-fed nation in history. According to the department, Americans spend only 17.7 percent of their disposable income on food,

Water, Water

“It is the upper-crust of farmers who are running the show,” says the frail, slowly speaking man, 83 years old, a scarf at his throat to protect against a chill, a cane by the door to help him walk. He is Dr. Paul S. Taylor, a storied man in this country among those concerned with questions of land, water, and agriculture. For 50 years, this man, chatting now at his desk in Barrows Hall on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley, has devoted himself to these matters, and he is talking about them now, farming in America and, specifically, a matter that seems almost to have consumed him, the question of Western water and what is called the 160-acre limitation. In 1902, when Congress passed the federal reclamation act, it stipulated that no farm irrigated with water from a federal irrigation project could exceed 160 acres-that old, fabled land measure of the Homestead Act. For Dr. Taylor, who has traveled this country, studying sharecroppers, migrant workers, men and women made landless by

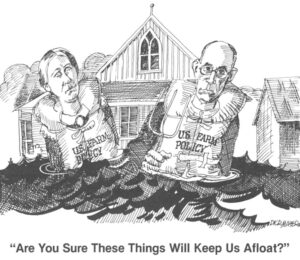

American Farm Policy

(a) Helps (b) Hurts The American Farm In the autumn of 1921, George N. Peek and Hugh S. Johnson, executives with the Moline Plow Company, Moline, Ill., proposed a plan to aid the American farmer. The early 1920s were hard times for farmers. Many had prospered in the first two decades of the century, particularly the years before and during the war. But the end of the war had brought a reduction in markets, and farm prices dropped dramatically. Farmers who had gone into dept to purchase more land when prices were high were unable, with falling prices, to make their mortgage payments. Many farmers lost their farms. Peek-a farm machinery executive for many years, a go-getter, and, particularly in his later years, a strong isolationist-and Johnson-a classmate of Douglas MacArthur at West Point, a brigadier by the end of the war, and, later in the 1930s, administrator of the National Recovery Administration-said that the farmer had one major enemy: surplus. Despite tariffs, Peek and Johnson said, surpluses forced American farm prices down. Yet, manufactured

The Man Who Sets Meat Prices

(Chicago) — Every day, Monday through Friday, starting at 7:45 a.m., 12 men, older, white-shirted fellows, take their seats at gray, office-style desks in a converted, 100-year-old townhouse, five minutes from Michigan Avenue. They spend the next eight hours or so on old, black telephones, talking the number of calls is in dispute — to slaughterers, brokers, Meat wholesalers, and other people in the meat business. By about 3:30 p.m., perhaps with the assistance of their director, 70-year-old Lester I. Norton, they determine the closing, or final prices for beef, pork, lamb and for many animal products, including hides, oils, glands and blood. These prices are printed on eight and one-half by 14-inch sheets of yellow paper, formally called the Daily Market & News Service, but generally known as the Yellow Sheet. The publications are then rushed into the mails for first class and special delivery shipment around the country. Lester L Norton These men, about whose techniques little is known, men whose work is unscrutinized by the government, set the nation’s meat prices. Used

The Story of an American Farmer

Seven thirty a.m. the sale barn. New Liberty, Iowa. A cold, rainy spring morning. The farmers in their blue and gray and white striped denim pants and jackets, their red, green and yellow billed caps, men of all sizes and appearances stand talking of how late plowing is this spring and of late spring plowing in seasons past. George, the spring of sixty-four was cold, too, darn it, the fellow says. We had to light hay fires, four nights in a row, May 20 to May 23, and you’d have to go some to find colder, wetter spring than that. The bidding begins at 9:30 a.m. Today, Tuesday, is the day the sale barn sells cattle ready for slaughter, fat cattle, as they are known, and group by group the huge, snorting cattle, manure stuck to their legs, are driven into the sale pen. George Bruhn, a farmer from Durant, ten miles to the southwest, buys nothing this day. He might have bid, taken some cattle and fed them some more, even though they are