By Bill Berkeley and Photos by AP/Wide World Photos

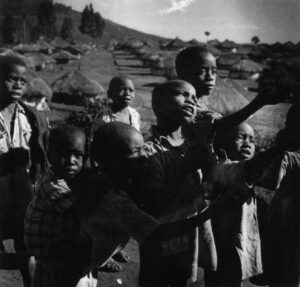

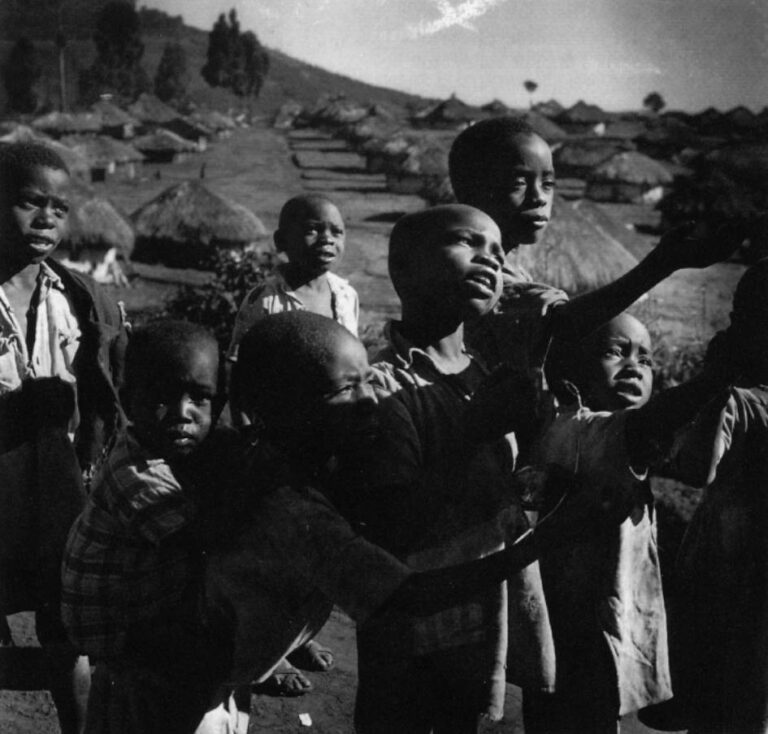

By the benighted standards of East Africa, the spectacle of refugees is all too grimly familiar. In a dense labyrinth of makeshift huts with scrap-metal walls and roofs fashioned from black plastic sheeting, children in rags, with bare feet and smudged faces, loiter aimlessly in a stream of muddy sewage. Their grim-faced parents, routed from their homes and stripped of their livelihoods, desperately scrounge for food and firewood in the forest nearby, their lives in chaos, their future uncertain. This could be anywhere in the counter-clockwise arc of despair that has blighted this part of the world for a generation: Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi.

But this is none of those exhausted battlegrounds — this is Kenya. Kenya has long been an exception to the regional rule of interminable wars and economic ruin. East Africa’s richest country by far, familiar to safari lovers and Robert Redford fans, Kenya is supposed to be the island of stability in a sea of calamities — the rare African success story where majestic game parks lure nearly a million foreign tourists on safari each year, where the telephones work, electricity flows, children go to school in shorts and knee socks, and even bureaucrats stick to the rules.

Kenya has long been a haven for other countries’ refugees. It is from Kenya’s up-to-standard ports and airfields that the world’s relief agencies wage their missions into neighboring war zones. So the sight of Kenyan refugees is both startling and more than a little disquieting.

It is a brilliant Saturday morning in western Kenya, and these are the lush green hills of Kenya’s most fertile farming region, known as the Rift Valley. In the days of British colonial rule these hills were called the “White Highlands.” This was exotic backdrop for the khaki-clad protagonists of Aldous Huxley, Beryl Markham, Isak Denisen. But the story being told today is of another era. It is a story of tribal militias, ethnic cleansing, and the danger of civil war.

“Twelve members of my family were displaced,” says James Mchama, 44-years-old, a refugee in a squalid camp near the town of Burnt Forest. He is a bewildered-looking man with tired eyes and white stubble. He wears a grimy second-hand jacket and tattered corduroys. The interview is conducted furtively in a shack. A sympathetic church worker minds the door, wary of informers. This is an officially declared “security zone;” barred to journalists.

Mchama says a band of as many as 200 arsonists attacked his farm last March, wielding bows and arrows. They looted and torched his house, and drove its panicked occupants into the bush. “We don’t return home because we fear we will be beaten again,” he says. “The attackers are still there.” Then he adds, “They were organized.” Organized by who? “We don’t want to say, really.”

What Mchama won’t say is that the mob that attacked his home was organized by agents of the Kenyan government. Mchama is Kikuyu, Kenya’s largest ethnic group. The attackers, he says, were Kalenjin, the small pastoral tribe of Kenya’s long-time President, Daniel arap Moi. Over the last three years more the 1,500 rural Kenyans have been killed — mostly Kikuyus like Mchama, as well as Luos and Luhyas — and 300,000 have been displaced from their homes in ethnic clashes that have shaken Kenya’s vaunted stability.

President Moi and officials in his government deflect responsibility for the violence by blaming age-old hatreds — triggered, they claim, by the advent of multi-party democracy. But the evidence of state complicity is strong, and it fits a pattern that is ruinously commonplace in Africa and elsewhere, where cynical despots provoke or manipulate ethnic divisions in order to obtain or hold power.

The emergence in Kenya of state-sponsored ethnic clashes has raised fears that East Africa’s last bastion of stability may be headed on the path of self-destruction so familiar to its neighbors. Over the past year many Kenyans witnessed with particular alarm the unfolding genocide in Rwanda and asked themselves, could it happen here?.

The New York-based human rights monitoring group Africa Watch, in a report titled “Divide and Rule,” compiled extensive evidence of government complicity in the clashes. It warned, “If action is not swiftly taken, there is a real danger that Kenya could descend into civil war.”

The fear of war is widespread — yet it has not happened. Kenya has somehow confounded perennial predictions of its imminent collapse. Sporadic clashes have continued, and many thousands of embittered victims remain displaced from their homes. Almost no one has been held accountable for the violence, and the danger of revenge attacks remains real. Yet alarmist visions of a wider conflagration have not been realized. Kenyans who look at their broken neighbors and ask, “could it happen here?” are also asking, “why hasn’t it happened here?”

“In fact, it’s a miracle that we have come this far without disintegrating,” says Gitobu Imanyara, a lawyer in Nairobi, the Kenyan capital, who has been at the forefront of Kenya’s decade-long struggle to establish a multi-party democracy. Like many others in Kenya, Imanyara has paid a price for his idealism. The magazine he published, the Nairobi Law Monthly, was raided repeatedly and ransacked, shut down, and finally driven out of business. Imanyara has been detained four times without charge. He was once held for two months in a psychiatric ward of a Nairobi prison after he published an editorial assailing President Moi for filling top jobs in his government based on ethnic affiliation rather than competence.

“We have a President who is determined to fulfill his prophesy of three years ago that the country is not cohesive enough for multi-party democracy,” Imanyara says. “His desire is to prove he was right, even if it means destroying Kenya as a country.”

Kenya, Imanyara noted, is a country of more than 40 ethnic groups. “The president has consistently pursued policies that encourage the various ethnic groups to think of themselves as different, not as one nation. The policy is to elevate ethnic identification and to exploit cultural prejudices and cultural differences.”

It was during the election campaign of 1992 that ethnic violence first erupted in the Rift Valley. A year earlier, concerted domestic and foreign pressures had forced President Moi to abandon single-party rule and open the way for multi-party democracy. For years Moi had resisted such a move, warning that multi-partyism would lead to tribal conflict. He maintains this is exactly what has happened.

In September 1993 Moi declared, “We have said in the past that when a multi-party system is introduced, it will create tribalism, divisions, and hatred and so on. That has now taken place.”

The tribal clashes have pitted members of President Moi’s own ethnic group, the Kalenjin, against larger ethnic communities which predominate in the political opposition. It became clear early on that the violence was being coordinated.

In September 1992 a parliamentary committee, formed exclusively of members of Moi’s own party, confirmed reports that high-ranking government officials had been involved in training and arming “Kalenjin warriors,” as they came to be known, to attack villages and drive away those from other ethnic groups.

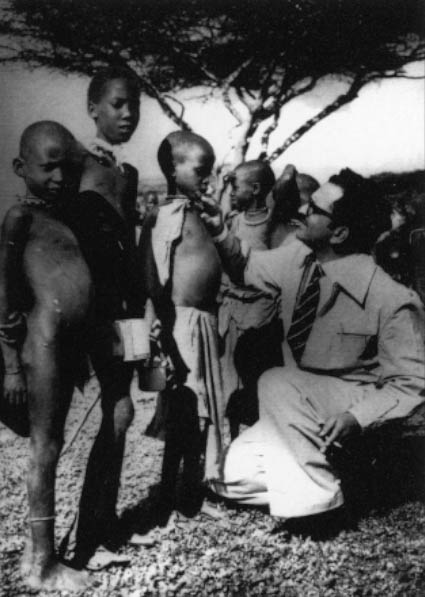

The pattern was much as James Machama remembers it. Hundreds of young men, dressed in an informal uniform of shorts and T-shirts, usually armed with bows and arrows, attacked the farms of Luos, Luhyas and Kikuyus, looting, killing and burning, and often illegally occupying the land. There is evidence that the attackers were paid, and that they were promised they could keep the land they seized. There have been retaliatory attacks and a cycle of violence has escalated.

The clashes have fed an atmosphere of growing hatred and suspicion between communities that have lived together peacefully for many years.

The violence has roots in genuine competition over land –a sensitive issue in a largely rural country with one of the highest population growth rates in the world. The Rift Valley was traditionally the home of pastoral groups, including the Kalenjin. During the colonial period, white settlers expropriated its fertile land. They staked out vast farms and recruited native Kenyans, notably Kikuyus and Luyas, to work their fields.

After independence in 1963, the British settlers began to sell off their lands. This provided Kenya’s first President, Jomo Kenyatta, a Kikuyu, with an answer to one of Kenya’s most pressing challenges, then as now: population growth and landlessness.

In the latter half of the 60’s, Kikuyus left their overcrowded homelands in droves to work and live in the Rift Valley. But as the land became scarce the Kikuyu migration created tensions between them and the pastoral tribes like the Kalenjin, who found themselves increasing penned in. At the time these tensions were mediated successfully by Kenyatta and his young Kalenjin Vice President, Daniel arap Moi.

What is striking in the current clashes is how President Moi, with his hold on power threatened, has seized on these old tensions and exacerbated them to destabilize his opponents and discredit multi-partyism.

President Moi and his associates have portrayed the calls for political pluralism and a multi-party system as an anti-Kalenjin movement. At public rallies, they have warned that the political opposition was arming itself as a plot to eliminate indigenous residents from the Rift Valley. They have referred to Kikuyus as “aliens” and “foreigners,” as opposed to Kalenjins and other pastoral tribes, whom they call “natives” and “original inhabitants.”

The violence has coincided with calls by high-ranking Kalenjins within Moi’s government for “majimboism,” a federal system based on ethnicity. Proponents of majimboism have called for the expulsion of all other ethnic groups from land occupied before the colonial era by the Kalenjin and other pastoral groups.

They have used the term “Madoadoa” — “black spots,” a chilling echo of South African terminology in the era of forced removals — to refer to land occupied by non-Kalenjins. Many Kenyans regard “Majimboism” as ethnic cleansing.

“They call it tribal clashes, but it is a political struggle for power,” says Reverend Earnest Murimi, of the Catholic Justice and Peace Commission, who has monitored the clashes and assisted the victims. “Moi supports single party rule not because he believes in it, it’s because he wants to maintain power. He fears a challenge.”

Rev. Murimi describes a series of public rallies at which the Kalenjin have been incited to attack their neighbors. “The rallies have been going on all over,” he says. “People are being provoked openly, and they are being paid. We have evidence. They said, ‘If you get rid of the people, you could get their property.’ I witnessed this myself.”

Saiko Wepukhulu, 64, a Luhya man whose family was driven off his land by a marauding gang of Kalenjin warriors, expressed little doubt about who was responsible for his predicament. Squatting on his haunches with a half dozen grizzled and embittered Luhya confederates in a squalid refugee settlement near the Uganda border, Wepukhulu declares: “They are to blame — the Kalenjin who pierce their ears — these are the people who did this to us. But it’s their leaders who began this violence. If it were only tribes…if it were just a question of tribes fighting each other, then the government would have intervened.”

The government’s response to the clashes has been characterized by inaction toward the attackers and hostility against those helping the victims. The government has declared clash areas “security zones” and barred journalists and others from them.

Asked what the solution might be, Wepukhulu replies, “It is multi-partyism that will eradicate this kind of misery. The parties are the ones who can fight for rights, and they don’t belong to one tribe.” What about Moi’s argument that multi-partyism leads to to tribalism? “Bubeyi!” Wepukhulu angrily replies in the Luhya language. “Bubeyi!” his confederates cry. “Bubeyi!” means “lies.”

“They are the people who are not ready to give up because they know what will happen to them,” Rev. Murimi of the Justice and Peace Commission says, referring to President Moi and his confederates. “These people have acquired a lot of property through illegal means and they can easily lose it. Of course they are doing anything to protect themselves.”

Politics in Kenya, as throughout much of the rest of Africa, has always been a means of safeguarding and securing “access to the meat.” Rampant corruption has flourished among a hand-full of Kenyan elites, and the gap has steadily widened between these rapacious few and the sullen “wananchi”, the masses.

The abuse of government as a cash cow did not originate with President Moi. Kenyatta, Kenya’s first President, and his family also amassed a huge fortune in land, precious gems, ivory and casinos during his rule from 1963 to 1978. But economists say that Kenyatta’s dealings were small compared to the systematic hold that Moi and some of his associates have acquired over the much larger Kenyan economy of of the 1980’s and 1990’s.

In 1991, the Bank of International Settlements listed Swiss-type protected bank accounts with Kenyan addresses amounting to $2.8 billion, making Kenya the fourth largest holder of such accounts in Africa after Nigeria, Zaire and Liberia — all African kleptocracies.

Using nominees and proxies, companies with links to Moi have skimmed huge profits off government contracts in wheat, oil, land, and particularly foreign aid. The Indian Ocean port of Mombasa is by most accounts a gateway for kickbacks and looting. In the Ministry of Finance, diplomats say, people sell to the highest bidder budget allocations that come with matching funds.

In the run-up to the 1992 election campaign, a network of “political banks” established by presidential cronies siphoned money out of the Central Bank into the ruling party’s election campaign. This resulted in a 35 percent growth in the money supply and 100 percent inflation.

The looting of the nation’s resources has provoked criticism, and a movement to challenge Moi’s absolute power. Moi has responded with an escalating campaign of detentions, press bannings, harassment, and political killings.

Although Kenya has never been a full-fledged police state, Moi in his first decade in power presided over the steady erosion of institutions of law and accountability. Through a succession of constitutional amendments beginning in 1982, Moi outlawed opposition parties and subordinated Parliament to his ruling party. He hobbled the independence of the judiciary by taking away life tenure for judges and the Attorney General, subjecting both to the will of the President. At one point in the mid-80’s, he scrapped the secret ballot in primary elections, replacing it with public queuing.

Kenyan politics abounds in mysterious disappearances and automobile accidents. The most infamous in recent years has been the still unresolved murder in 1990 of the country’s Foreign Minister, Robert Ouko. A retired Scotland Yard detective who investigated the minister’s death concluded that he was abducted and shot by government agents because he was preparing a report on corrupt ministers in Moi’s government. A principal suspect, never charged, was President Moi’s closest confidant and bag man, Nicholas Biwott. Biwott is widely regarded as the brains behind the clashes in the Rift Valley.

Moi’s ability to control events in Kenya began to change with the end of the Cold War, when his role as a reliable client of the west ceased to matter. Beginning in 1991, Moi’s domestic opponents found new allies among western donor countries, including the United States. Concerted domestic and foreign pressure, including the suspension of aid by the World Bank and bilateral donors, forced Moi to repeal the 1982 amendment to the Constitution and legalize a multi-party system. A year later, in December 1992, elections finally took place.

President Moi and his ruling party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), were returned to power with barely a third of the total vote, their victory owing largely to divisions among the opposition parties. But the tactic of stoking those divisions on ethnic grounds may come back to haunt Kenya.

Could Rwanda happen here? The spectre of genocide is extreme, but many Kenyans whose lives have been shattered see little hope that enlightened forces can prevail over Moi’s machinations. “This is in the power of only one man,” says Androniko Maima, 63, a Lou peasant who was driven off his cooperative farm by the “Nandi warriors,” a notorious Kalenjin militia, in 1992. “He can create anything to continue in power for all his life. That’s why all African countries are suffering, because of the few heads of government who want to stay in power. They are thinking of the wealth. They are fearing that they will have to pay for their crimes.”

Why has Kenya not already disintegrated? The explanations go to the heart of the country’s history.

Kenyans have already experienced one war, the Mau Mau guerrilla insurgency against the British in the 1950’s. More than 11,000 Mau Mau insurgents were killed in that war — Africa’s first independence war. Many thousands more were detained, tortured, or displaced to concentration camps where conditions were so horrific that many died. Importantly, nearly all those directly involved in the Mau Mau struggle were Kikuyu. The Kikuyu know what it means to be at war; Kikuyu elders have been counselling restraint.

James Muigai, 58-years-old, another grizzled Kikuyu who was driven from his farm by Kalenjin warriors last March, was 16-years-old in 1953 when his family was displaced during the Mau Mau war. They had been working on Lord Delamere’s “Equator Ranch.” Three of his cousins, suspected Mau Mau guerrillas, were killed by Kikuyu “home guards.

“The memories of Mau Mau are still with us,” Muigai said, “and so we do not favor any war or conflict because they only bring misery. The most important thing we want is peace.”

Gibson Kamau Kuria: “The fact that civil war is not there despite all the provocation is an indication of how well understood and dreaded the prospect of war is.”

A second factor is that Kenyans generally are better educated than their neighbors. A generation of Kenyans has grown up with the benefits of relative stability, and so there is a substantial middle class that cuts across ethnic lines. Whereas elsewhere in Africa the vertical ties of ethnicity represent virtually the only source of identity, Kenya’s middle class cuts horizontally across ethnic lines. Urban Kenyans don’t regard other groups as foreign. The Kenyans who have been most provoked by the clashes — the Kikuyu and the Luo–also tend to be the best educated. The Kikuyu are Kenya’s entrepreneurs; they have the most to lose from a ruinous war.

Gibson Kamau Kuria, a Kikuyu lawyer, is the dean of Kenya’s human rights movement. He once spent 10 months in prison for his advocacy. He put it this way: “The Kikuyus and the Luos are most involved in the market economy, and they were in the forefront of the struggle for independence, as well as in the move toward democracy. The significance of this fact is that to these ethnic groups, the concept of a modern state and the concept of a modern economy are well-understood. They understand that the problem is one of bad government and corrupt economics, not bad tribes.”

“The Kalenjin are not a united front,” said Bethwell Kipligat, a retired diplomat who is Kalenjin, who for years was a close advisor to Moi on international affairs. “I am Nandi,” Kiligat explained, referring to a sub-group of the Kalenjin that has been deeply involved in the clashes. “The Nandi leadership in that district and other Kalenjin were aggrieved by the clashes and helped the victims. And they spoke out. This is a sign of hope.”

A related factor, Kipligat noted, is that Kenya over the years has developed a vigorous civil society that also cuts across ethnic lines. The Catholic Church, the Kenya Law Society, the independent press — all have been battling for democratic rights and have proved resilient despite years of harassment and repression. With the end of the Cold War, these institutions have found encouragement from the western donor countries, and gained in strength.

“Before, the West had supported the regime. The civil society became stronger than the regime. There was no choice but for the president to change course.”

Kipligat was alluding to a final factor: that the President is a shrewd survivor who thus far managed to avoid the path of self-destruction.

“One thing that helped is that Moi is a very articulate political chess player,” observes Kiruri Kamau, managing editor of the repeatedly harassed but still independent weekly, The People: “He makes some tactical retreats when he thinks he is pushing people too far. Moi is very cunning. He is calculating. He is not reckless like Doe.” He is referring to the late President Samuel K. Doe of Liberia, whose thuggish regime was consumed, finally, by its own ruthless folly.

“Moi realized that these things had gone too far,” Kamau says. “If there is a war, Moi would stand to lose so much.”

©1995 Bill Berkeley

Bill Berkeley is a freelance writer in New York city who has been reporting in African on his Patterson fellowship.