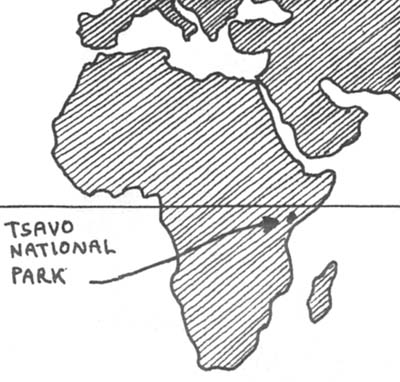

Voi, Kenya

Probably no other controversy has done more to divide the ranks of conservationists around the world or more to cripple ecological research in East Africa than that involving the elephants of Tsavo.

Because of pressures outside the huge 8,300 square -mile Tsavo National Park, thousands of elephants have been crowding into the sanctuary, swelling the population to somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000, and making it the largest remaining concentration of elephants in the world.

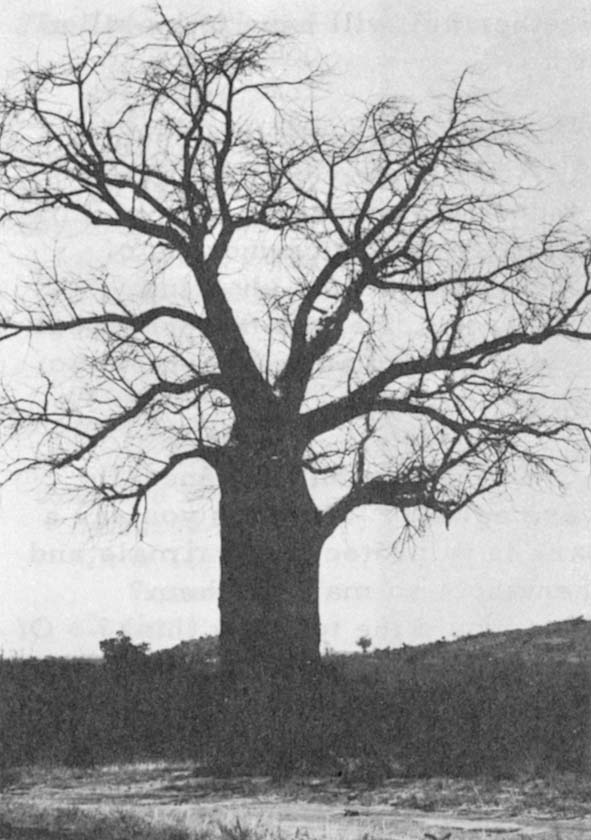

Because elephants eat so much and push down so many trees in the course of their activities, large concentrations can devastate an area. Tsavo, once a lush land of dense bush and trees is today a sad landscape of bare ground and struggling grasses, strewn with the skeletons of downed trees. Because the park receives very little rain, some scientists have said the destruction could eventually turn Tsavo into a desert, providing so little food that most of the elephants would eventually starve to death. The long-term result could be a “population crash” that would wipe out elephants in the very place set aside to protect them.

Three years ago a drought reduced the already damaged vegetation so severely that between 5,000 and 6,000 elephants died of malnutrition. Since then, still more elephants have entered the park, seeking refuge from hunters and expanding agriculture. The population may again be as high as before the drought.

Further droughts and massive die-offs are almost certain in coming months and years.

When a scientific team recommended shooting 3,000 elephants for research purposes and indicated it might be necessary to shoot many more to bring the population back into balance with its environment, many conservationists recoiled in horror. Killing the animals they were trying to protect hardly fit the traditional conservation ethic.

Dr. Richard Laws, the scientist, was recognized as one of the top men in his field, but the outcry forced him to quit. The park warden, a former officer of the Kenya Regiment of British colonial days who bottle-feeds orphaned baby elephants, vowed never to permit such a scheme.

The rumor became widespread that the whole proposal was a money-making scheme by the scientists in conspiracy with a commercial concern that was to do the shooting. Indeed, it has been estimated that selling the ivory and skins from the 3,000 elephants to be shot for research would have earned a profit of over 1. 5 million dollars.

The episode was so bitter and so widely misunderstood that it has turned many of East Africa’s park wardens – who are frequently retired military men with little more than a hunter’s myth-filled knowledge of ecology – into active opponents of research aimed at better park management. Outside Africa, many conservationists have come to doubt the motives of scientists in Africa. The Tsavo Research Project, which did the original study and which was on its way to becoming a major research center on large-mammal ecology, today remains a small, struggling organization unable even to properly observe the extraordinary phenomenon taking place on its doorstep.

When it was founded in 1966, the Research Project received a 220,000 dollar grant from the Ford Foundation to cover three years. When the grant expired in 1969, the financially pressed Kenya National Parks took over but only at some 42,000 dollars a year, less than 60 percent as much as the project had been getting in its first years. To make ends meet, many studies have been abandoned, and others have been kept going only with small donations from various private conservation organizations. Most of this money comes from the United States.

While in the United States teams of scientists concentrate on the subtle changes in individual ponds, one of the largest and most spectacular ecological transformations in the world is mostly ignored at Tsavo. The two remaining staff scientists are unable to determine accurately even as elemental a fact as the number of elephants in the park. Although methods for doing this exist, they are too costly and require considerable expertise.

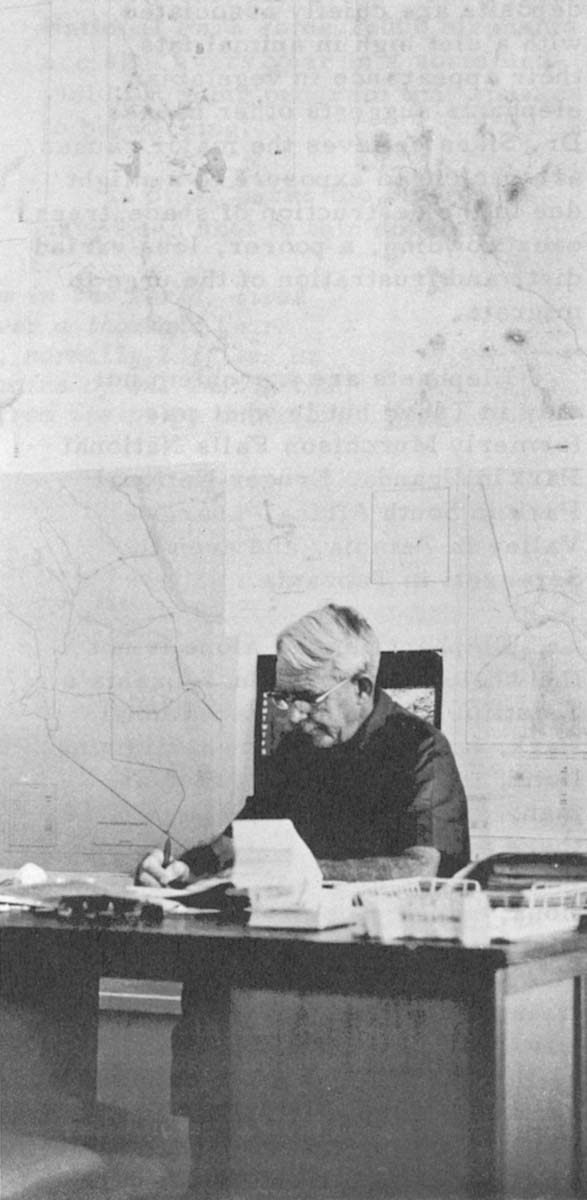

If little is being done to understand the phenomenon, nothing is being done to control or manage it. It may, in fact, be too late. Today vast areas of the park, which is larger than New Jersey, have become what Dr. Philip Glover, the present director of the Research Project, calls “elephant slums.”

Dr. Glover, who is 65 years old and has spent nearly all his scientific career in Africa, stood outside the Project’s laboratory one recent morning and squinted into the distance, pointing:

“All that out there used to be thick bush. Now look at it. Just a year or so ago this area right around the building was so thick you couldn’t see beyond. Now they’re coming right up to the houses.”

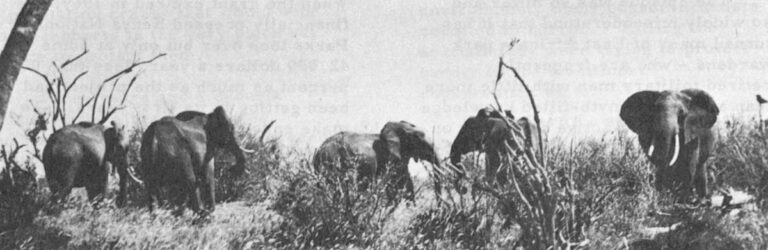

Dead and twisted trees lay all about. The ground was a patchwork of dry grass and bare dusty soil. In the distance a family of elephants grazed, ripping up tussocks of standing hay with their trunks and stuffing them into their mouths. A full grown elephant needs about 700 pounds of grass, leaves and twigs a day. How they get it from such a meagre landscape is hard to see. Possibly they don’t anymore.

“It takes a lot of patience to stand by and do nothing” Dr. Glover said. There was sadness in his voice, and a touch of anger. “But it’s a natural phenomenon” he quickly added, as if to check an emotion that shouldn’t fog a scientist’s view.

If the trees cannot survive the elephants, they will go, and plants that can survive – such as grasses – will come. If the elephants cannot continue in such numbers, as many will starve as the land cannot support. Few ecosystems are constant and unchanging and there is really no such thing as a “pristine” state of nature.

Still, ecosystems rarely change as rapidly as has Tsavo, or in a spectacle so saddening. Much of Tsavo looks as if a war had just ended there. It is a ravaged land. The elephants shuffling about, scrounging bits of grass under fallen trees, are the war’s orphans, and its combatants.

Problems of high elephant density are developing in several parks around Africa, all more or less for the same reasons – increased competition from human beings who are settling and farming larger and larger areas of once-wild land where elephants lived. Because of these factors, and increased illegal hunting for ivory, Africa’s elephant population as a whole is dwindling. Some say rapidly. (Although there are still over five million elephants in Africa, a century ago there were probably twice as many). These same pressures are forcing the intelligent beasts to seek safety in the national parks. Consequently, the parks are witnessing a phenomenal compression of the remaining elephant numbers. This has led to the erroneous belief among some that the parks have over-protected elephants, leading them to a population explosion. In tr uth, the phenomenon is both a serious sign of the threat to elephants outside the parks and itself a direct threat to those inside the parks.

In the more severely over-populated parks, the elephants are showing signs of ill health. Fertility is declining and infant mortality is increasing. The calving interval, normally about four years (the gestation period is 22 months), has lengthened to as much as nine years in some populations. In the first four years of an elephant’s life the mortality rate is normally around five percent a year; in the crowded herds it is now up to 20 percent a year. Thus the majority of elephants born fail to reach reproductive age, which begins at around ten to twelve years.

Even the surviving adult elephants show signs of disease. Dr. Sylvia K. Sikes believes that Tsavo elephants are suffering diseases of the heart and arteries as a direct result of the deterioration of their habitat. Her autopsies, comparing elephants of the crowded Tsavo wastelands with those living less crowded in denser vegetation, showed clear differences in the amount of fatty deposits on artery walls.

Because in other animals such deposits are chiefly associated with a diet high in animal fats, their appearance in vegetarian elephants suggests other causes. Dr. Sikes believes the major causes are prolonged exposure to sunlight due to the destruction of shade trees, over-crowding, a poorer, less varied diet, and frustration of the urge to migrate.

Elephants are a problem not only in Tsavo but in what was formerly Murchison Falls National Park in Uganda, Kruger National Park in South Africa, Luangwa Valley in Zambia, and even the Serengeti in Tanzania.

Elephant density alone is not the whole problem. In Tanzania’s beautiful Lake Manyara National Park, famous for its tree-climbing lions, there are three times as many elephants per square mile as there are in Tsavo. (In fact, one theory explaining why the Manyara lions, unlike most of the others in Africa, spend most of their days sleeping in trees is that they are trying to keep out of the elephants’ way.) And yet, there appears to be little problem in Manyara. It remains green and thickly vegetated. The difference is rainfall, the single most important factor in almost every African ecosystem. Tsavo can count on between ten and twenty inches of rain in good years, much less in drought years. Manyara gets more than twice as much.

Virtually the only seasons in East Africa are wet ones and dry ones. In some places, however, the “rainy” season may bring only two or three inches of water. A few miles away it may bring 60 inches. During the rainy season, the grass, bushes and trees are green. But within weeks after the last rainfall, everything dries up. Grass turns brown and many trees drop their leaves. Growth nearly stops and the herbivores must make do with whatever standing hay is left plus the brief blooms of green that follow the rare dry season shower. In Tsavo even the rainy season’s water falls in extremely isolated patches. Biochemical studies have shown that during the dry season, a young elephant’s growth virtually stops, much as the growth of trees stops in winter. Only in the rainy season is the food sufficient to allow growth to resume.

Somehow elephants can sense a recent rainfall miles away. Thus after each isolated shower, elephants come from miles around to take advantage of the brief greening while it lasts.

Depending on the amount and distribution of a region’s rainfall it can comfortably support a larger or smaller population of elephants. Tsavo can handle a few thousand – it did for many years – but not the 20,000 to 30,000 it has.

Another factor contributing to Tsavo’s situation is the fact that the elephants are trapped there. There is still some land outside the park in which to roam but not much. Although very little is known about the long-term activities of elephant herds, it is believed that – before man became such an intrusive factor, carving up the African scene with farms and villages – elephants migrated in great herds, leaving an area before their brutish habits had destroyed it and not returning for perhaps decades. Thus, there was time for the damaged landscape to regenerate. Today few elephants are able to escape from the parks. Their destruction continues unrelieved.

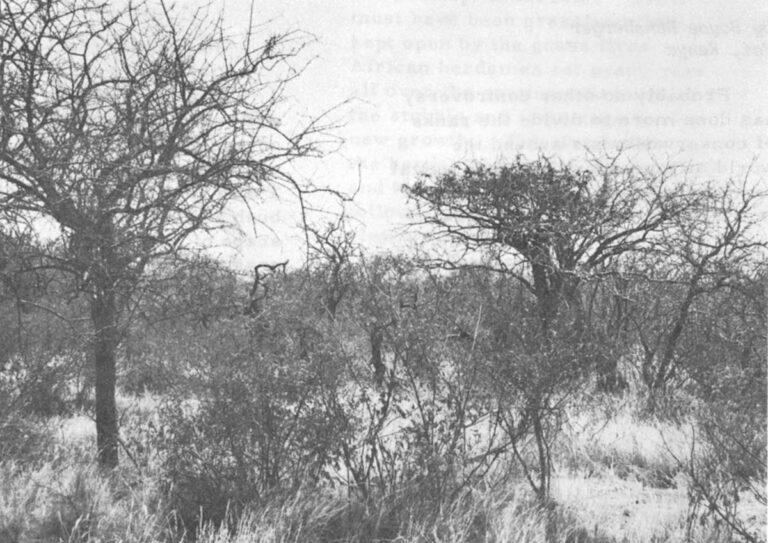

BEFORE elephant damage became unusually severe beginning in the 1950s, most of Tsavo looked like this area now outside the park.

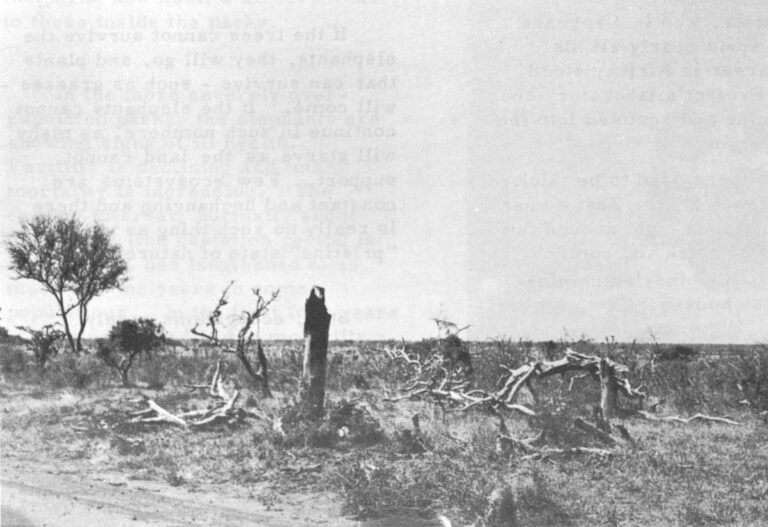

AFTER the density exceeded the ability of the ecosystem to regenerate its vegetation, much of the park now looks like this.

The most widely proposed solution is to cull a proportion of the elephants, reducing their numbers to a level that can coexist with the environment. Elephant cropping programs have been or are being tried in several places. In Murchison Falls 2,000 of some 10, 000 elephants were shot. This relieved the pressure at first but gradually the natural limits on fertility began to fall. Suddenly relieved of pressure, the elephants began multiplying faster and may reach their old numbers again.

What was first thought to be a long-term solution was not. The prospect of repeated elephant killings in a national park appalls many conservationists. Not in South Africa, however. In Kruger National Park some 1,000 elephants are shot every year in a sustained-yield cropping program that appears to be working.

In other parks too, elephants have been shot to thin out their numbers. But, for a variety of emotional and political reasons, not in Tsavo.

“If it could be done without the objections I see,” said Dr. Glover, “I’d crop in Tsavo. But there are just too many problems that I don’t think can be overcome. So, we might as well make the best of it and consider this a control while everybody else tries cropping.”

Although Tsavo does not make a scientifically neat control in the experiment (there are too many other uncontrolled variables), there is no doubt that scientists are learning, at least in gross terms, what happens when you let an elephant population continue under very extreme circumstances.

A few years ago Dr. Richard Laws, the first director of the Tsavo Research Project, had other ideas for the park. He wanted to make a detailed study of the population structure and breeding patterns of the Tsavo elephants. Possibly that information and some mathematics from the science of population dynamics would show whether the natural decreases in fertility and infant survival would eventually limit elephant numbers. Or, if that seemed too slow a process to save the park, the study could suggest how many and which elephants to cull to most effectively give the vegetation a chance to regenerate.

In 1966, along with Ian Parker, a former game warden turned elephant cropper who had made a small fortune selling the ivory and skins of the elephants he shot in Murchison Park, Dr. Laws shot a sample of 300 elephants so they could be accurately aged and sexed, and pathologies diagnosed and pregnancies in progress counted.

This, however, was not enough to get the whole story, Dr. Laws contended. He believed, based on his studies of elephant distribution in the park, that there were ten distinct populations of elephants that lived in more or less discrete regions. They appeared to have different age structures and, therefore, could be expected to have different reproductive potentials. He said that 300 elephants would have to be taken from each population to get the full picture. Thus 2,700 more elephants would have to be shot.

The outcry killed the plan. Many people doubted the evidence for discrete populations.

“I’m not convinced”, said the Minister of Tourism and Wildlife, “that it is necessary to kill 3,000 elephants in an experiment aimed at seeing how many elephants will eventually have to be killed or whether any will have to be killed at all.”

Park Warden David Sheldrick had, just a few years earlier, conducted a massive anti-poaching campaign that put hundreds of people into jail for shooting elephants. He was not prepared to turn around and pay hunters to kill 3,000.

Conservationists generally were aghast. How can you say a park is to protect the animals and then shoot so many of them? What would the tourists think? Of all Africa’s animals, elephants are among the most loved by conservationists, probably because of their size, intelligence, and close family structure that gives the illusion of adhering to the finest human values.

There were also technical objections. Some contended that you cannot shoot some elephants without, in effect, embittering the survivors and turning them into man-killers for the rest of their days. The old story that elephants never forget, especially when they or their kind have been wronged, is, surprisingly, widely believed among hunters and wardens. Laws and Parker say there is no basis for it and that, in fact, the heavy culling in Murchison Falls did not produce vicious survivors.

The warden and Dr. Laws never got along well in the first place and Dr. Laws, faced with what he saw as an untenable situation, resigned.

Nothing further has been done except to gauge in very rough terms the continuing effects of the elephants.

Then, in 1970 and 1971 a severe drought hit. From April of 1970 until late November of 1971 most of the park received less than ten inches of rain. Periods of up to five months would go by without a single drop.

Elephants began dying by the hundreds, not of thirst – there were still a few permanent water sources but of starvation. The grasses and leaves they needed had long since gone. In desperation, many elephants ate the bare twigs and branches that remained. The elephants starved to death with their stomachs full – of wood. The first to go were the youngest and the oldest. Unable to keep up with the herds as they ranged farther and farther in search of food, the weakest ones dropped. For most of the little ones that died, their nursing mothers died also. When her baby falls, a mother elephant will rarely abandon it.

Park rangers reported seeing many mothers desperately trying to raise their dead babies, nudging with their feet or lifting with their trunks. For hours they struggled hopelessly, themselves growing weaker. Refusing to abandon their calves to find food or water, somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 nursing mother elephants died, comprising nearly half the drought’s total.

Month after month, as the siege continued, more and more elephants succumbed. Eventually the toll exceeded the park staff’s ability even to keep up the count over the vast area. In an attempt to learn more about the elephants that died, rangers collected the lower jaw from each vulture-cleaned skeleton. Details of a jaw’s size and teeth reveal the animal’s age and sex. Eventually 3,400 jaws were collected and officials estimated that probably another 2,000 or more were inaccessible or had deteriorated before they could be collected.

Twice as many died as the Laws-Parker cropping scheme would have taken, and in a manner that yielded very little information of use in preventing further disasters. Supporters of the plan observed that the cropping would at least have reduced the overall demand for food during the drought. It could well have led to a larger cropping designed to reduce the population to a size that would not only survive dry years, but that would allow the vegetation to come back in wet years.

There were too many elephants and, one way or another, some had to die.

In addition to elephants, Tsavo has the world’s largest concentration of rhinoceroses. Perhaps 5,000 of this severely declining species lived there until the 1970-71 drought. Some 600 died then. Had the elephant population been smaller, the rhinos undoubtedly would have survived. Not long before, a private organization had spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to rescue just 60 rhinos from precarious situations outside various parks. They were released into Tsavo and other parks. Many of those who supported the rhino operation opposed the elephant cropping scheme. The same money spent on research at Tsavo might have saved hundreds of rhinos as well as elephants.

Now, in 1973, the situation is again precarious. Although the rains have been nearly normal, Tsavo’s vegetation remains severely reduced due to the destruction of so many trees. The normal dry season now beginning could kill more elephants.

“You watch,” Dr. Glover said. “About October I think we’ll see a few more dying. I could be wrong but it’s difficult to see how. Look at it already. The rains ended only a couple of weeks ago.”

Many waterholes were already dry. Except along the rivers, what grass there was, was brown. The prospect is for three or four more months with little or no rain.

Little by little the laws of ecology will see that there are no more elephants surviving than the land can support. Gradually, nature will redress the imbalance. In coming years, almost certainly, many thousands more elephants will die. Probably only a few score will go each year until about 1980 when another of the periodic severe droughts is expected. There was one in 1950 when the elephants were still too few to be hurt. There was one in 1960 when some 300 rhinos died but still no elephants. But by 1970 the population was too big. That drought cut the population but since then, more elephants have been forced into the park and 1980 could be the worst year of all.

It is now probably too late for any cropping scheme intended to save Tsavo’s former habitat. It is largely gone.

“If they wanted to keep Tsavo the way it was,” said Dr. Walter Leuthold, the only other staff scientist at the Project besides Dr. Glover, “they should have started shooting elephants ten or fifteen years ago. Now, if they want the old vegetation to come back, I think they’d have to shoot three-quarters of them (at least 15,000 elephants). Three thousand won’t do it.”

Not everyone sees the loss of the trees as a bad thing. Grassland habitats favor a greater variety of large mammals such as antelopes, zebras and their predators. If Tsavo can have more of these, as well as elephants, the thinking goes, it will attract more tourists.

Already, elephants have opened up the habitat so much that plains animals are increasing in numbers.

“Some people think someday this could be another Serengeti,” Dr. Glover said. “That’s just wishful thinking. The Serengeti has twice as much rain and it’s more evenly distributed. We’ll get a few more but Tsavo could never support the herds that people go to Serengeti for. ” The old man shook his head. “Wishful thinking. Let the elephants go, they say. I say, it’ll never happen. Well, I shouldn’t say ‘never’, but I can’t see it. Wishful thinking and facts are two different things.”

Still, there is some reason to believe that eventually, perhaps in fifty or a hundred years, the trees may come back to Tsavo. If the elephant numbers diminish and stay low and fires are prevented, seedling trees could grow. It may even have happened once before. In the 1880s, according to the accounts of explorers and archaeological findings, Galla herdsmen lived in the area and there were no elephants to speak of. Cattle are not kept in forests. Tsavo must have been grassland then, kept open by the grass fires African herdsmen set every year all over the continent to burn off the stubble and encourage tender new growth. But, for some reason the herdsmen left the area. Bush and trees must have moved in, followed by a modest number of elephants, creating the Tsavo known in the first half of this century.

It may happen again, slowly, but only after man or nature does something about the elephants.

Received in New York on July 16, 1973

©1973 Boyce Rensberger

Boyce Rensberger, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner with support from the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Rensberger., the Alicia Patterson Foundation, and the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.