Perhaps the best known and most enduring single feature of East Africa is the massive, snow crested mound of Kilimanjaro, rising through the clouds to over 19,000 feet.

In the foreground of many thousands of tourists’ photographs of the mountain, however, is one of the most fragile and transitory features of Africa — the splendid yellow-barked acacia woodlands of Amboseli with herds of elephant or zebra or giraffe spectacularly silhouetted against the mountain.

For some 20 years the once lush vegetation of Amboseli has been gradually dying, turning parts of Kenya’s most profitable game park into a barren landscape and threatening to destroy much of what remains of one of Africa’s best wildlife viewing areas. Since 1950 some 90 percent of the trees have died. Scrubby bushes have taken their place and the change in habitat may lead to a decline in the game animals for which Amboseli is famous.

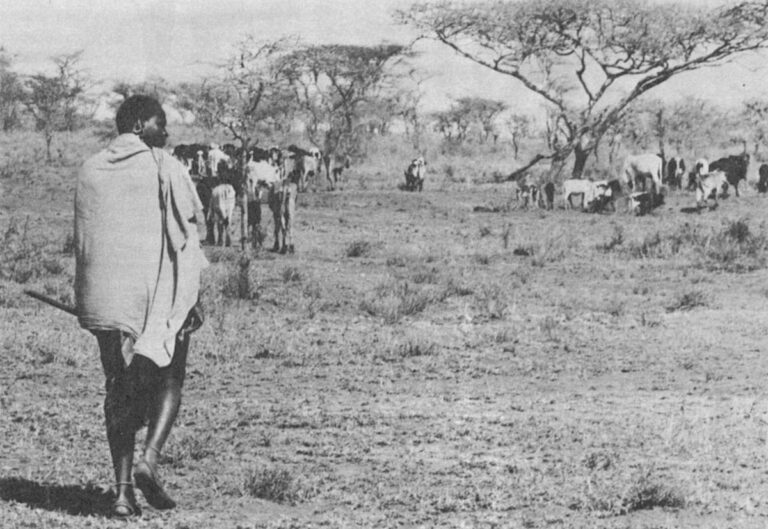

Although the destruction of the habitat has long been attributed to overgrazing by the cattle of the semi-nomadic Masaj tribe (legally entitled to use the reserve until it becomes a national park) and damage by elephants, recent scientific studies have largely exonerated the accused and revealed instead that a completely natural phenomenon is the basic cause of the change.

The study has also suggested that the same phenomenon, part of a natural cycle extending over many decades, has occurred in the past and that the present seeming deterioration of the habitat may eventually reverse itself and return Amboseli to its former glories decades from now.

The Amboseli phenomenon dramatically illustrates a principle of ecology that is usually less obvious: There is no such thing as a pristine state of nature. Habitats are continually changing everywhere, responding to completely natural causes from cycles of rainfall abundance and drought to geologic faulting that rents and drains a lake to population explosions that force habitat-modif ying animals into new areas.

It is a common enough phenomenon almost everywhere that it is likely to confound most efforts to draw boundaries between what shall be left as wilderness and what shall be “developed”. Nature rarely maintains a habitat in an unchanging condition from year to year. Nature keeps her balance over very large areas, sometimes over the planet as a whole. Deficits may occur in one area but they are compensated for by surplusses elsewhere.

As long as such major ecological factors as the water cycle (global circulation of clouds and oceans and continental flow of rivers and underground water) obey no political boundaries, many things that are inside a national park will continue to depend on factors outside the park, whether those factors are man’s work or nature’s.

The Everglades will die because farmers hundreds of miles away drain bogs for cultivation. And Amboseli will lose its remarkable variety of wildlife because, ironically, its rainfall has increased in the last few decades.

Dr. David Western of the University of Nairobi has found, after a five-year study of Amboseli, that the trees and grass are dying because of this sequence of events:

Rainfall in recent decades has been greater than in the decades before.

This has raised the underground water table, bringing subterranean water up near the roots of the trees.

But the water is carrying with it dissolved mineral salts that were deposited in the ground long ago.

Roots immersed in water with a too-high salt content will shrivel because the laws of osmosis will cause water to flow out of the root into the soil instead of the other way around. (Osmosis, quite simply, moves water across a membrane from a region of lower mineral content to a region of higher mineralization. The “goal” of osmosis is to achieve equilibrium between two originally unequal concentrations of minerals. Groundwater normally flows through the cell membrane into the root when the soil water is less mineralized than the contents of the cell. At Amboseli the reverse situation is true.)

The same thing doesn’t always happen elsewhere there are rising water tables because Amboseli has an unusually rich concentration of minerals in its soil.

This is because, a few thousand years ago, Amboseli had a large shallow lake into which several rivers drained but which had no outlet. It lost water only by evaporation, which resulted in gradually increasing concentrations of dissolved minerals in the lake that had been brought in by the streams. (Today in East Africa there are many such “soda lakes” or “alkaline lakes”. Lake Nakuru, the famous flamingo sanctuary, is one.) Eventually Lake Amboseli dried up, leaving thick crusts of minerals on the ground just like the deposits in an old teakettle. Later, rains redissolved the minerals and washed them down into the depths of the soil.

Western said records from explorers of the last century, a time of heavy rainfall as now, indicate that Amboseli was then very much like what it now seems to be becoming. One old record even states that Amboseli was dominated by a kind of bush known to favor soil of high salinity. The Masai, who have long lived in the area, told Western that the woodlands did not grow up in Amboseli until the turn of the century or shortly thereafter.

“We now know,” Western said, “that Amboseli is subject to periodic changes and must be regarded as an ecosystem in a continually dynamic state.”

Until Western’s detailed ecological analysis of Amboseli, traditional conservationists and tourists saw no reason to doubt that Amboseli’s decline was the result purely of trampling and overgrazing by the vast herds of cattle kept by the Masai, the tall, elegant tribesmen of East Africa who have long disdained Western ways and, for that matter, the ways of every other African tribe.

The huge dust clouds swirling up from a herd of cattle being driven to water were proof positive to Europeans that the Masai were responsible for the destruction they saw. After all, they noted, it couldn’t be drought because the rains in recent years had been better than ever. The trees were said to be going as the result of elephant damage as well and, indeed, there was some elephant damage.

Conservation organizations mounted strong campaigns to evict the Masai from their traditional lands.

To learn whether overgrazing was really at fault, Western began a study of Masai methods of cattle keeping.

His attempts to learn how the Masai decide where to graze their cattle or when to move on to another area were initially futile. Questions like, “Why do you move your cattle from this place to that?” brought answers like, “Because it’s time to move them.” Only when he could persuade the Masai that a white man actually wanted to know the technical aspects of raising Masai cattle, did they begin to open up.

Western said he found that the Masai were extraordinarily knowledgeable about the growth cycles of the various plants in their region and that they moved their cattle from one grazing area to another so as to minimize damage to the habitat. Scouts are sent out to look for areas where isolated showers have produced a brief greening. If the greenest grass is too far from drinking water to drive the cattle back and forth, the Masai donkeys are brought into action. Long trains of donkeys with water containers on their backs are led by the women back and forth between the water hole and the pasture. If the available grass is too little in an area the big herds are split into smaller ones which scatter widely over the region to reduce the grazing pressure.

“The Masai really live quite harmoniously with their environment”, Western said. To live any other way in an arid climate would, of course, be suicidal and the Masai have been living in their present lands for at least 200 years.

Western also suspected something other than cattle were at fault because the areas with the most marked decline in vegetation had been free of cattle for up to 20 years and the areas with the heaviest Masai settlement had the healthiest trees in the region.

Attention turned to elephants as the possible culprit. Over 80 percent of the failing trees showed signs of elephant damage. But 17 percent of the dead and dying trees showed no sign of elephant activity. Soil studies eventually revealed that these trees were rooted in earth with a high salinity. Further study found that virtually all of the most severely elephant-damaged areas also had salty soil.

Western has concluded that as increasing soil salinity killed off trees, fewer and fewer were left to withstand the elephant damage that had previously been negligible. The result was an apparent but nonexistent increase in elephant damage. Conservation officials had considered shooting some of the elephants to halt the woodland decline. That plan has now been dropped.

If the Masai cattle are not the chief culprit in Amboseli’s decline, the tribe’s young warriors do pose a threat to the reserve’s rhinoceros population. A study made by Western and the then warden of Amboseli, Daniel M. Sindiyo, himself a Masai, has found that the rhinos are being speared so frequently that, if the practice is not curtailed, there will be no more rhinos in Amboseli by 1977.

Although rhinos are still rather common elsewhere and reintroduction could boost their numbers, the Amboseli population seems to be genetically unusual in that the rhinos have extraordinarily long horns, some measuring over four feet in length. Until recently the rhinos have been the biggest draw for tourists. The tourists, in turn, have made Amboseli one of the most profitable of game parks, producing some 200,000 dollars a year in revenue. Amboseli alone earns 75 percent of the revenue produced in its district.

Yet, virtually none of the money filters down to the Masai living in the area. That, Western believes, is why the young warriors, a class with few duties, have no compunctions about spearing rhinos for kicks. Theyused to prove their bravery by raiding cattle from neighbors but that has largely been stopped. Some rhinos are also killed by herdsmen defending an area for their cattle and others are lost to poachers seeking the horn.

If rhino spearing can be stopped (national park status would exclude Masai from living in the area) and if the replacement of the dying trees by salt-tolerant bush does not remove so much favorable habitat that there are not enough game animals to attract tourists, Amboseli will face a further problem — the tourists themselves. Their harrassment of lions and cheetahs has driven some away and may have led to missed kills that caused some cubs to starve. And the criss-crossing of safari vehicles over the fragile alkaline grasses is actually destroying more vegetation than the Masai cattle, Western said.

At present some 100,000 people visit Amboseli each year but the number is growing so fast that by 1980 the number may reach half a million — most of them determined to see elephant, rhino, lion, cheetah and buffalo in a single day. At present it is still possible to do this. That is Amboseli’s great attraction.

Received in New York on November 30, 1973

©1973 Boyce Rensberger

Boyce Rensberger is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner with support from the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Rensberger, the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.