Koobi Fora, Kenya

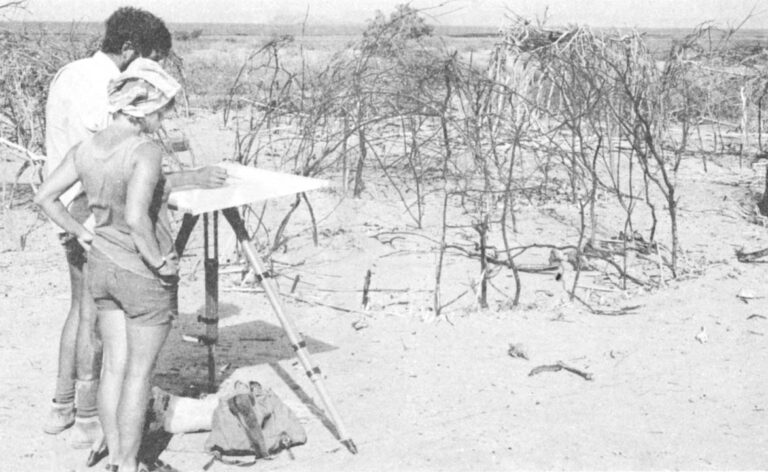

On this barren, crocodile-infested spit of sand that juts into Kenya’s remote Lake Rudolf stands the base camp of the most successful early-man fossil-hunting expedition ever mounted. From the semi-permanent grass-roofed huts clustered on the point to catch lake breezes, Richard Leakey and a team of scientists that sometimes swells to two dozen range out over a thousand square miles of hot, hilly thorn-bush country to collect the fossilized bones of various ancestors and cousins of the human species.

In the six years since young Leakey, son of the pioneering couple, laid claim to what is now known as East Rudolf, he and his colleagues have recovered the partial remains of 110 individuals who lived anywhere from 1.3 to 4.0 million years ago and who stood very close to, if not actually in man’s ancestral lineage.

Unlike most other fossil grounds in Africa, East Rudolf yields not just scattered fragments of bones but, perhaps due to unusual conditions of preservation, whole intact skulls and complete long limb bones. Leakey’s people have even found clusters of several bones from a single individual. Leakey says that among the next 50 hominids to be found he thinks the odds should give him an unprecedented complete skeleton of a single individual of an extinct form of man of such age.

That may just be young Richard Leakey talking, the 30-year-old, brash, audacious inheritor of the controversial Leakey mantle from his late father. But then again, given the Leakey knack for going out on limbs that strengthen under them, he may very well find that skeleton before long.

Or, more likely, one of his keen-eyed African fossil hunters will find it for him. For Richard Leakey seldom gets to spend more than weekends at his lakeside camp. He spends most of his time in his Nairobi office or at the stick of his single-engined Cessna, shuttling among the far-flung facilities of the National Museums of Kenya of which he is director. For a few weeks or months each year he tours England and the United States, speaking before packed auditoriums and meeting with scientists and philanthropists to further the work of his expedition. He is also heavily involved in national wildlife and environmental policy making in Kenya.

But, when he can manage, East Rudolf is where he clearly prefers to be. It is, even by East African standards, a world away from the world most of us know.

It is about as far away from a city as you can get in East Africa — 400 air miles north of Nairobi, almost to Ethiopia or the Sudan. Until Leakey formed a hunch about the area it was largely unknown to all but scattered bands of nomadic herdsmen. In 1967 Leakey, then a part of Clark Howell’s Omo expedition in Ethiopia, was shuttling between the Omo and Nairobi, studying the East Rudolf formations as he passed over.

“I don’t know exactly what it was but I just had this feeling,” Richard recalled. “The [geological) beds looked right and I was sure there had to be fossils down there.”

A brief visit by helicopter turned up pebble choppers not unlike those first found by his parents at Olduvai Gorge and a full-scale expedition was organized for the following year. Over succeeding seasons Leakey tried various combinations of aircraft, Land-Rovers and camels to explore the area. He found fossils everywhere and says that one problem in the early days was convincing his colleagues to spend less time picking up fossils and more time exploring to learn the extent of the deposits.

In the exuberance and, some argue, in the inexperience of the East Rudolf expedition’s early days, many fossils were haphazardly collected without adequate documentation of where they came from in the geological strata. Fossils are very nearly useless without some idea of their age and association with other fossils. Without this information they cannot be dated.

In recent years life at East Rudolf has assumed a more measured and disciplined pace but Richard and his colleagues still wince when reminded of the early days. If, through carelessness, some finds were lost to science, the East Rudolf researchers have more than made up for it in the richness of discoveries made since then. Almost every hominid paleontologist looks enviously at Leakey’s province and hundreds of students apply each year for nonexistent positions with the project.

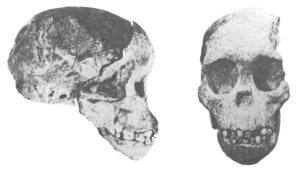

Perhaps the most celebrated, and most controversial, of Leakey’s finds — an artist’s version of it even made Playboy — is the skull known as 1470, so-called from the number assigned to it in the expedition’s catalog of fossils.

In the summer of 1972 one of Leakey’s crew, Bernard Ngeneo, spotted some pieces of broken fossilized bone that had characteristic hominid features. According to the rule Leakey has laid down, Ngeneo, put the pieces down as soon as he recognized their potential significance. He marked the spot with a stick and sent word to Leakey. Richard will not permit anyone but himself, not even his most trusted co-workers with fancy academic degrees, to take up hominid fossils from wherever they are spotted in or on the ground. He does, however, give full credit to the finder in the published scientific report. The names of several of Leakey’s unschooled but highly skilled field workers are familiar to scientists around the world who read the reports.

Leakey was summoned and he collected the fragments. Within a matter of days Leakey’s wife, Meave, and a colleague, paleontologist Alan Walker, fitted the pieces together into a large-brained skull of strikingly modern proportions. The modernness of the skull was unusually startling because the creature had died and been buried under the ash of what appears to be a 2.6 million-year-old volcanic eruption.

Although there has been controversy, some of it still unresolved, over the skull’s true age (it may be as much as half a million years younger than claimed), few experts deny its significance. The 1470 skull is persuasive evidence that long before it had been thought to have happened, there were hominids with strikingly large brains striding the earth. The cranial capacity of 1470 is estimated at 810 cubic centimeters, a substantial jump beyond the 500-plus range of the Australopithecine “ape-men” toward the 1200-cc range of modern man.

In the two years since the discovery of 1470, Leakey’s crew has found still more uncharacteristic hominid fossils, several of them exhibiting combinations of anatomic features that do not fit the previously accepted scenarios of how man evolved. Unless East Rudolf has preserved an extraordinary selection of aberrant types, Leakey has evidence that there were not just one or two hominid lineages in existence at a given time but three or four and perhaps more. Some appear strikingly modern in one anatomic feature, say teeth or cranial capacity, but distinctly primitive in another. The impression is that there were many types of early man all living in more or less the same place at the same time. Perhaps they made war. Perhaps they made love. In any event, the picture of man’s evolution that once seemed to be getting clearer must now be redrawn in large part.

The new finds have now shown us that we are not the products of a simple, linear evolutionary sequence with older model hominids quietly becoming extinct as their more advanced descendents came on the scene. Rather, our ancestors seem to have lived in a world of several types of man. Distinct types may have gone their separate ways, paying no more attention to one another than closely related types of antelope do grazing on the same plains. Or two types may have interbred. We may be the product of a complex web of evolving lineages.

East Rudolf must have been a region with sufficient ecological diversity to have allowed various types of closely related hominids to have arisen and thrive for hundreds of thousands of years. (It should be noted that the various types of ancient hominids would have no relationship to the various races of man living today. All modern races of man stem from a single surviving lineage.)

Although Lake Rudolf existed in those days, the region today is quite different from what it was then. It now is a drier, less hospitable place and, given the drought affecting Africa in recent years, the region is getting drier still. Game is sparse but not absent. Antelopes such as topi and oryx graze in the area. There are lions with a reputation for man-eating. And cheetahs, one of the rarest of the African cats, prowl about. And, for much of the year, so do the scientists and technicians, searching for fossils and for the geological clues that put the bones in context.

Whether the next few field seasons produce a whole skeleton or not, continuing study in the area over the next few years is likely to continue the flow of unexpected new evidence that will force continuing revision of the story of how man evolved.

Received in New York on July 2, 1974

©1974 Boyce Rensberger

Boyce Rensberger recently completed a year as an Alicia Patterson Foundation fellow with support from The L.S.B. Leakey Foundation. This article may be reprinted with credit to Mr. Rensberger, The Alicia Patterson Foundation and The L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.