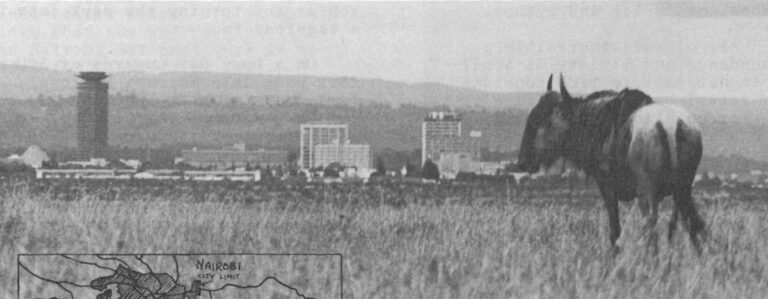

Nairobi, Kenya

From the traffic jams and high-rise office buildings of downtown Nairobi it is just five miles to the Pleistocene age of mammals. On the outskirts of this burgeoning metropolis of nearly 600,000 there remains a remarkable concentration of wildlife, the like of which has not been seen in most of the world for thousands of years.

Protected within Nairobi National Park, a mere 44 square miles, leopards prowl the forest at night, thousands of antelopes graze the plains by day and, within sight of the city’s taller buildings, the rhinoceros — a true relic of prehistoric times — plods through the bush.

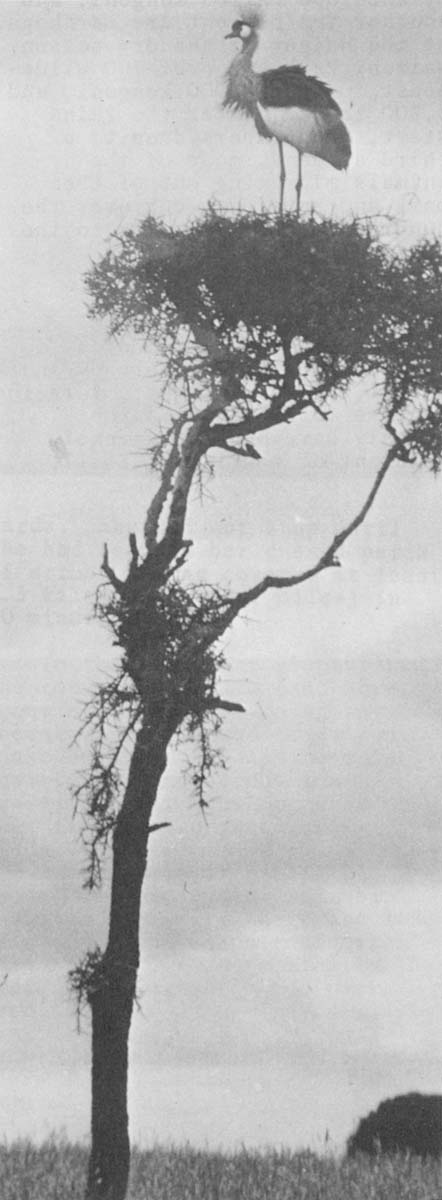

At the height of the dry season, when animals from the largely unpopulated region to the south crowd toward the park’s waterholes, more than 18,000 mammals of 78 species live in the park. They include virtually all the big game animals associated with East Africa except the elephant. In addition, there are nearly 400 species of birds and several dozen of reptiles including cobra, crocodile and python.

All of this incredible abundance and variety is available not just to rich tourists on safari but to the office worker on a long lunch hour, the passenger with a few hours to kill during a layover at nearby Embakasi Airport, and the whole family on a Sunday afternoon outing.

Therein lies the park’s uniqueness and also its greatest threat.

On weekends so many cars crowd into the park that it looks more like a Fourth of July picnic ground than an African wilderness. Visitors wanting a close-up view have harried the lions so much that they can no longer hunt successfully during the day. Cars leaving the roads to cut across the plains in search of animals have scarred the grassland so much that soil erosion is becoming a problem. And, perhaps most serious, urbanization and expanding agriculture threaten to surround the park, cutting off annual migration routes and turning the park into a cageless zoo.

On a busy day upwards of 500 cars pour into Nairobi National Park, many of them ignoring the 20 m.p.h. speed limit to roar up and down the dirt roads looking for lions, the most popular animal. From a high point in the park one can scan the plains and, for miles around, see rooster-tails of dust spiralling up behind the weekend lion hunters.

Tourists spotting a pride sleeping peacefully will often drive straight across the grassland and park ten or fifteen feet away. Because, for safety reasons, visitors are not allowed to get out of their cars, the challenge is to drive as close as possible to the animals. The father who can maneuvre the family bus through tall grass and across a shallow stream bed to get a better view of the lions wins extra admiration from his kids. Within minutes, other sedans, station wagons, Land Rovers and microbuses converge on the pride, turning what had been a quiet, shady thorn tree into center stage. It is an old joke that the way to find lions in Nairobi National Park is to look for clusters of cars.

One recent Sunday afternoon 14 vehicles surrounded a clump of bushes where a mother and two cubs waited, peering out every now and then to see whether it was safe to come out.

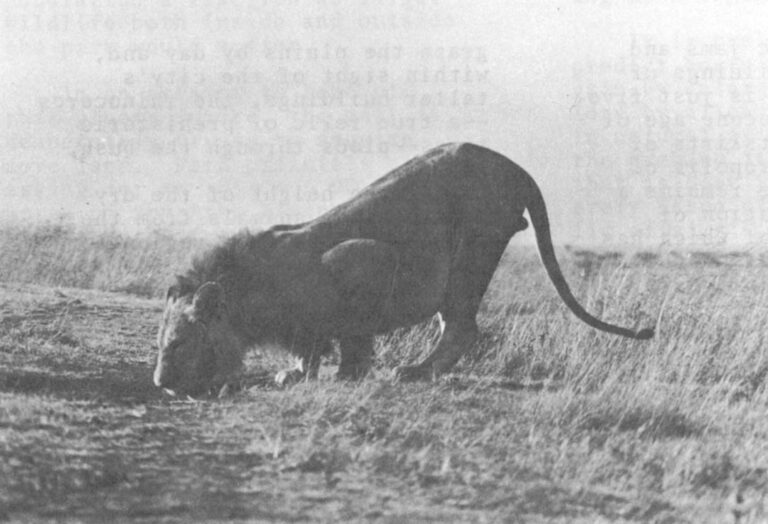

“The pressure on lions is quite severe here. Everybody who comes to Nairobi Park would like to see lions,” says Hassan S. Mohamed, the chief warden. “They are always being watched. They are always being surrounded by cars and they have completely changed their habit of hunting during the day. They don’t hunt because as soon as a lion gets up and starts following an animal, then he has maybe ten, twenty cars following him to see what he does.”

Lacking speed, a 400-pound lion must rely on patient, quiet stalking of its prey if it is to get close enough to make a kill. Half a dozen cars trailing behind, jockeying for a better view, do not help. As a result, the Nairobi Park lions hunt only at dawn and dusk and on moonlit nights.

“If you see a lion hunting during the day, he must be very, very hungry and desperate,” Mohamed said.

Although harrassment has caused the lions to change their behavior patterns, it has not caused any severe hardship. The park has more than enough prey animals to support the 32 lions that live there. On the average, each lion kills about 20 animals a year. About 50 percent are wildebeest (also known as gnu), 20 percent are zebras, ten percent are a kind of antelope called kongoni, and another ten percent are warthogs. At the height of the dry season, Nairobi Park has over 700 wildebeest, about 2,000 kongoni, and 2,200 zebra. After the rains start, the numbers drop to a third as many, most of the animals migrating out of the park and spreading out over the hundreds of square miles to the south.

There is no record of a visitor having been hurt by an animal, provoked or not, largely because most of the Nairobi animals have become extremely tolerant of tourists. Still, the risk is there and is well illustrated by incidents turned up in a study of the fate of rhinoceroses captured outside the park and released into the sanctuary.

Patrick H. Hamilton and John M. King, both wildlife biologists, found that although the rhinos, unaccustomed to tourists, have chased cars from time to time, impacts have been rare. There were only two in a recent 27-month period, both, oddly, on the same day. One involved a bull released 13 months earlier.

“The bull was reported to have met a Ford Zephyr on a blind corner with a bank on one side and a gorge on the other,” Hamilton and King wrote in their report. “He charged from a distance of about 15 meters, hooked at the radiator grille three times, breaking a headlight, puncturing the radiator and lifting the bonnet.”

The second incident involved a female rhino that had been in the park but five weeks:

“Cow M was encountered moving at a fast trot away from the center of the plains to her preferred area below the release pen. The cause of her agitation appeared to be a white Mercedes hire-car in pursuit. The Mercedes was unable to keep up with the rhinoceros, which crossed a ridge and joined a road that led homewards. Unfortunately, a stationary Holden Premier, covered with baboons, blocked her path. The rhinoceros broke into a gallop at about 25 meters, hit the front bumper, rose in the air like a pole vaulter, stamped the bonnet with her front feet and slid backwards down the nearside of the car. The animal then chased a Citroen for a short distance before continuing west-wards. She did not stop until she had reached her chosen patch of scrub, having covered at least 6.5 kilometers (four miles) in 30 minutes.”

In the land that glamourized the four-wheel drive Land Rover, ignoring roads and “going anywhere” is a hallowed tradition. Consequently, there is no rule against driving across the grassy plains, crushing what can be a fragile ecosystem.

Although it is barely 15 miles from one end of Nairobi Park to the other, there are 165 miles of established roads from which one can see practically every square foot of the park. Despite this, eager and seemingly myopic visitors have plowed a cobweb of tracks across the park. There are more miles of tracks than of roads.

In a single afternoon, twenty or thirty cars heading off the road to find a lion or a rhino can make a track that will not disappear for five years.

“This is becoming a very serious problem,” Mohamed said.

Inside the park the greatest threat is automobiles. This kongoni, or hartebeest, watched Sunday afternoon safarists roar by. It turned and ambled off to its right…

…only to be nearly run down by a speeding Volvo. The animals are so accustomed to cars, they let them approach quite close. But if a person steps outside, they’re off.

“If we continue having growing numbers of cars coming into the park, it is going to damage the vegetation and cause erosion and, in the long run, it could turn the park into a desert.”

Mohamed, an African who has been in charge of Nairobi Park for four years, said he has been trying to get the trustees of Kenya National Parks to approve a rule requiring that cars remain on the roads. “I hope to make it this year,” he said.

Enforcing such a rule will not be easy. At any given time there is rarely more than one assistant warden patrolling the park. Often he is watching the cluster around a lion, making sure that nobody throws a beer can to make the lion “do something” or, worse, that nobody gets out of his car. (In parks all over East Africa, tourists thinking that lions are big pussycats have been mauled and killed.)

In the long run, Mohamed speculates, it may be necessary to limit the number of cars in the park. The tourist industry in Kenya is exploding — in 1960 about 12,000 foreigners visited the game parks; by 1970 the number was 232,000. The increase is continuing. Compared with the 500 cars that now visit on a Sunday, Nairobi Park can expect some 2,000 by 1978 if the present trend continues. That would come to 45 cars per square mile or, if they all stayed on the roads, one car every 440 feet.

Park officials are considering such alternatives as forcing people to come on buses, or limiting the number of cars by requiring advance reservations for a limited number of tickets.

Such alternatives would not be taken well, especially by the thousands of Nairobi residents who like to drop in to the park when they have a spare hour or two to get away from it all. (Nairobi is as busy and tension-filled as any American city its size.)

It is one thing to encounter a cheetah or a rhino or a buffalo from the solitude of one’s own car – it is an event. It would be quite another thing to watch from a crowded bus — more like going to a movie, or perhaps to the zoo.

Rules may solve the problems originating inside the park. But more drastic measures may be required to solve the potentially far more serious problems coming from outside the park.

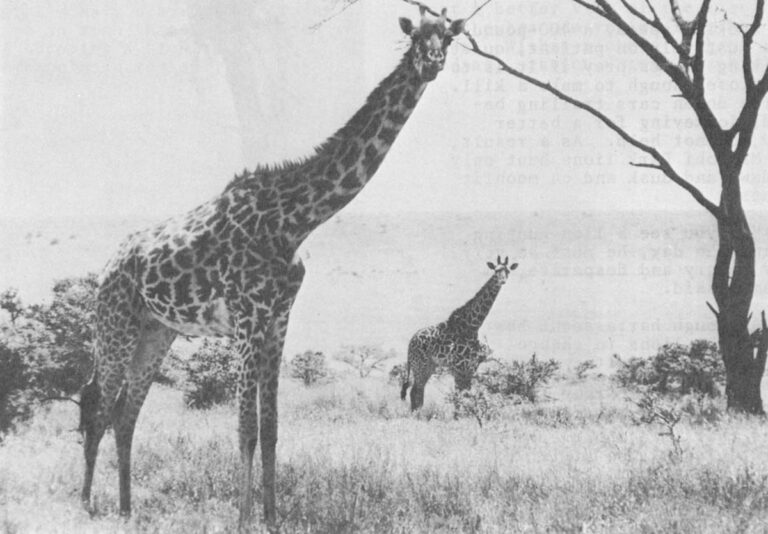

No East African national park is a self-contained eco-system. In all of them, animals migrate in and out, depending on the season. Because many of the parks contain natural or man-made sources of water, they are refuges in the dry seasons when water holes outside the park dry up. Several species, zebra and wildebeest, for example, may migrate hundreds of miles, crowding toward water in the dry season and spreading out to take advantage of new grass and the temporary water supplies during the wet season.

Nairobi National Park is no exception. Thousands of animals come and go each season. If its boundaries were fenced, the natural balance would soon begin to tilt drastically. Trapped in the park, the animals would soon overgraze the plains by remaining in high concentrations the year round. (The lower animal density during the wet season allows enough new grass to grow to sustain the higher density for the few months it is in the park.) Severe overgrazing could turn the park into a desert. Many of those animals kept out of the park would die of thirst when the seasonal water holes dried up.

Although the northern and western boundaries of the park have been fenced to keep the animals from blundering onto highways, the long side of the park away from the city is not fenced. The park opens into largely undeveloped land known as the Athi Plains.

“Ten years ago,” Mohamed said, “the whole area south of the park was completely empty of human settlement. But now people are settling there and this is becoming a serious problem.”

A number of Masai families, pushed out of their traditional areas by growing populations, have moved near the park. Some are grazing their cattle just outside the park. A meatpacking plant has been built nearby. And the suburban housing developments of Nairobi are about to spill onto the Athi Plains.

“In a few years the whole migration route could be completely blocked,” Mohamed said.

Sealed off from the larger ecosystem of which it is only a part, Nairobi National Park could continue, but only with an animal population a fraction as large. Wildlife both inside and outside the park would suffer.

In an attempt to head off that gloomy future, the park is desperately trying to acquire more land. Park officials are asking for an adjacent 90,000 acres of the Athi Plains, an addition that would quintuple the size of the park and almost certainly assure it a healthy future for at least a few more decades. The additional land would also disperse the vehicular traffic, reducing it to a more acceptable density.

“Our problem,” Mohamed said, echoing the sentiments of conservationists everywhere, “is the politicians. I don’t want to tell you what I think of them.You know politicians.”

Land and the rights of the African people to it have long been paramount issues in Kenya politics. It was the crux of the opposition to the colonial settlers, and today independent Kenya’s political leaders are still struggling to deliver on their promise to assure every African his own “shamba,” his own plot of land. The land distribution program is barely able to keep pace with one of the world’s highest birth rates.

Consequently, any scheme to deny human settlement on so vast a tract of land near the city seems doomed to failure. Making parkland of the additional 90,000 acres would mean going beyond that, and forcibly removing the people already there.

Still, much of Nairobi’s prosperity is due to an annual influx of nearly 250,000 foreign tourists and their millions of dollars, pounds, marks and yen. If Nairobi National Park is allowed to deteriorate, tourists may quickly head for other parts of East Africa instead of spending much time in Nairobi.

It is probably impossible to predict how much Kenya would gain by enlarging the park, or lose by allowing it to decline in natural attractiveness. And, the problem involves a conflict that is deeply felt in almost every issue of East African public affairs: The rights and immediate needs of the “wananchi” or common people, versus the claimed benefits to the nebulous and remote “national economy”.

Like most things in Kenya these days, the outcome does not seem predictable. Most likely, however, the animals will win only if they can prove that they will more than pay their way in shillings and cents.

Received in New York on June 29, 1973

©1973 Boyce Rensberger

Boyce Rensberger, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner with support from the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Rensberger, the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.