By the time the average American reaches 70, he will have consumed an equivalent of 150 head of cattle, 2,400 chickens, 225 lambs, 26 sheep, 310 hogs, 26 acres of grain and 50 acres of fruit and vegetables.

— Texas A&M University research handout.

I took a walk not too long ago with my friend Joe Raber, who is a farmer. I say this with some caution., because if we were to be possessive about these things Joe is actually my brother’s friend. Also, I am hard put to explain to my friend, Ralph Keyes, who is writing a book about “community” in America, why I call Joe, whom I have seen face-to-face only three times, a “friend.” Definitions are difficult for us, as we are in our formative years. Ralph and Joe are 28, I am 29. My brother, who is 30, seems to have these things under control.

Joe is a farmer; that I am sure of. He owns 16 cows and ninety pigs and grows corn and oats and hay on ninety-six acres in Holmes County, Ohio, which is near where I grew up. I would like to see somebody try to prove that Joe Raber is not a farmer.

Contrary to the popular image, pigs do not lay about in the mud like slugs all day. They are considered to be among the most intelligent of barnyard denizens. A recent study showed that pigs, if given the choice of mud and an air-condition

I stopped by to see him because he is, in fact, and I told him so. “I am studying changing patterns in work habits in the country,” I said to him, “and I am particularly interested in talking to you as a representative of the breed of worker that most of this country reveres as the very epitome of the Protestant work ethic.” Joe has recently transferred his religious practice from the Amish church to the Mennonite, and warmed to this topic, though I soon had to detour him. “No one works harder than the farmer,” I said, by way of explanation.

The other sign of human ambition that you can see on a walk around Joe’s holdings is the barn on his brother’s farm, half a mile away. That’s all. This is the country. On our walk, however, we never strayed far from the pond into which my brother and brother-in-law were foolishly casting fish lines, and in the distance we could hear the raucous tinkle of six childrens’ voices, in chorus. It was, in short, the pastoral simplicity that city folk imagine they would, if they only could, participate in. I strove mightily — and successfully, as it will be shown here — to keep our minds away from these distractions and on the topic of work.

I will allow my brother one interjection, however. I told Joe, whose pigs provide the significant profit in his operation, that I had seen inflated prices on pig snouts in the supermarkets of Manhattan. “You mean they really sell pig noses?” he said, in the manner of one who has found that the moon landings were not staged in a studio after all. And, “I wonder what they look like when they’re fried or whatever.” I corrected, tentatively, that this item generally is dumped into soup stock, like salt pork, for flavor. My brother, a rude wit, interrupted, “If people knew what they root around in, they wouldn’t use them for flavor.”

This deterred me from assuring Joe that his lack of understanding about city folk often is equaled, vice versa as it were, by the city dweller’s misconceptions about farmers. I, a city person all my life, was never so aware of this as when I moved from Ohio to Long Island and sensed that certain of my new acquaintances were uncomfortable that I did not affect Oshkosh b’gosh overalls and a straw hat.

The cause of this I am reasonably certain is that urban creatures, having elevated anyone able to use his hands to the status of household god, and having lost the ability to imagine an egg or a cut of meat as predating the supermarket’s sanitary wrapping, have inevitably translated to awe their admiration for these able bodies, the farmer included. The psychological distance between looking at a hen in the children’s zoo and reaching under her to steal an egg is too great for the imagination to travel, I am saying, and we cannot compare ourselves at all favorably to the man who not only has a hammer on his workbench but also enough spare batteries to service the kids’ new Christmas toys.

But, for purposes of our conversation, this was entirely speculative and I was happy not to be given the chance to burden my friend with it. For my disguise was as the man of no opinion, and I hoped to wheedle from Joe Raber some support for my secret assumption that the poor farmer is saddled unfairly with the reputation of being America’s prototypical hard worker — another citified misconception.

Faced with starting the wheedle somewhere, I asked Joe whether he could compare farming in any way to a nine-to-five job. “No, it’s different,” he said with a soft finality. “You’re not tied to it the way you are to a factory. You probably work longer hours, and yet, like today, I didn’t have to ask the boss to go. Which is nice.”

Although he grew up on the farm he now works, Joe has a basis for comparison. He has spent a summer as a mason’s assistant, cut timber for a year, served two years in a hospital in lieu of military service (a standard experience in the Amish and Mennonite communities), was a deliveryman for six months, and did odd jobs in a pallet factory during a winter. Of the last, he volunteered, “I worked the night shift and so I sort of did a little bit of everything in the shop, but even that got monotonous. I couldn’t figure out how a guy could work on the same saw day after day, week after week. I just found out all over again how I appreciate farming. There’s a lot of things I don’t like, there’s a lot of work I don’t like, but it’s still not monotonous like most factory jobs.”

His tour of duty at the pallet factory, brought about by a poor financial return on the farm one season, came after he had suffered the excesses of youth and made, finally, the decision to farm as a career. He said: “Dad there, he was gettin’ old, and he used to say, ‘Wel, look, if you don’t want to farm, why we’ll just forget about it, we’ll sell the place,’ and I says, ‘Yeah, yeah, I want to farm it, I want to farm it,’ but I really didn’t want to till I just felt sort of forced into it, I think, during my two years at the hospital, living in town, which I didn’t like, being so different from the country where I was raised.” Looking back at that decision, Joe termed it good fortune. “I guess I’m lucky,” he said. “I’d sure hate to go buy a farm these days, and start from scratch.”

I suppose Joe or any other farmer would be foolhardy to go out and start from scratch these days. At the turn of the century, the census bureau tells us, sixty percent of the population lived in rural areas. By 1970, 69 percent of the people were holed up in cities of fifty thousand or more in population, or their suburbs. More to the point, in the decade 1960-70 the population climbed by twenty-four million while the population of cities went up by twenty-six million.

Some people, not without good motives, want to move out. The result is that the price of land has escalated, under the pressure of school-teachers and dentists looking for a couple of acres away from it all. I talked to a man in Wayne County, Ohio, who was being asked to pay $500 an acre for adjacent land that he hoped to use as pasture for one cow. He could not afford it. Near Galena, Ill., the son of a farmer, whose father had been forced to sell his land because of ill health, worried that by the time his military commitment was completed the price of land would be beyond his means. Farm acreage was selling for between $300 and $500. A real estate agent in Cornell, Wis., agreed that those prices were fair, and said that property values were steadily appreciating at a fifteen percent rate. In Albany township, Vt., where one acquaintance of mine purchased land ten years ago at nine dollars an acre, and a friend bought just a half-dozen years ago at $50, farm acreage is at $300 and rising. The farmer, who tends not to have that much ready cash, is being shut out of the land market, and, in fact, in some cases is cheerfully joining the race to raise prices.

“I wish I had more land, ” Joe Raber said, and we chuckled at examples of “land fever” we each had encountered. “See, it works this way,” Joe said, volunteering to give the farmer’s motivation. “If you get more land, you think, ‘Well, look, I’m gonna need a bigger tractor to farm all this.’ Okay. Now you got a bigger tractor, and, ‘Hey, I can handle another field or two with this…’ and it keeps on going. In a way, I think Amish farmers have an advantage. (The Amish Church prohibits the ownership of mechanized equipment among its members.) When I used horses, I had just about all I could handle. There was no desire to have more land, because by the time I had all the crops in, planted and harvested, I was satisfied. I had worked hard enough.”

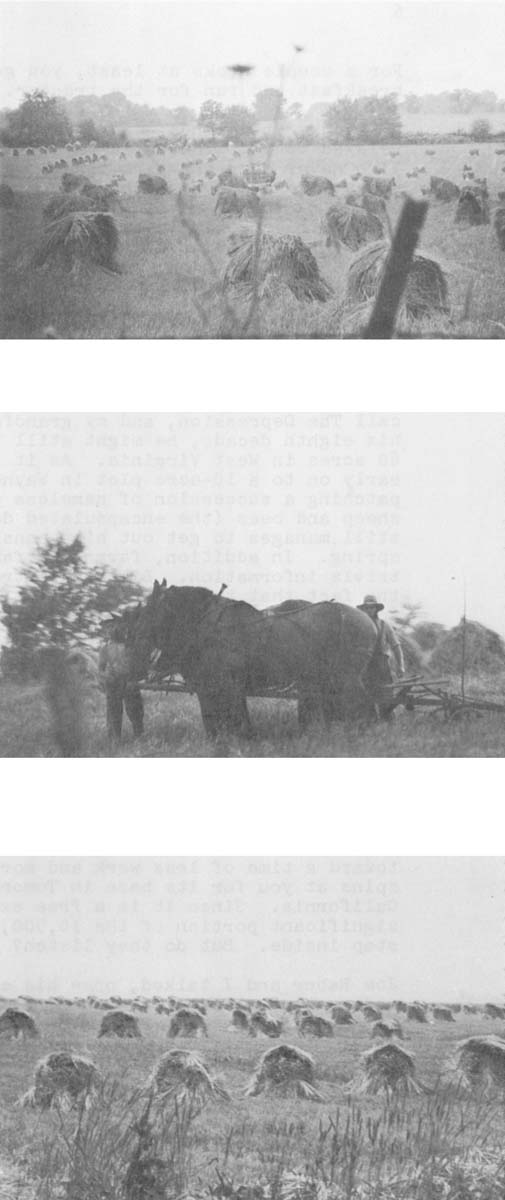

Amish farmers will not allow their pictures to be taken. It is against their religious tenets. Some of these photographs are illicit. Because they have no mechanized equipment with which to beat out the wheat kernels and discard the chaff (these photographs happen to be of oats), the Amish farmers thresh by hand.

They stack the wheat first, to encourage it to dry, in bundles called shocks. Don’t touch them.

If you have been looking through this laundry-list of statistics to the motives for this conversation, you will realize that this was just the opening I was looking for. I asked Joe what a farmer’s typical work day consists of.

“0h,” he said in an offhand manner, “I get up around six, at least I try to…it’s later some times. I do the milking and then eat breakfast. After that, why I start whatever needs to be done that day, and then I eat dinner, or lunch, or whatever you want to call it, at twelve, and then work some more until about five. We eat supper and then do the milking again, and then I usually don’t do very much. Usually I spend the rest of the evening with the family” (wife and two pre-school children).

Well, my gambit hadn’t worked, quite. I still needed to know the quality of the work. So I asked Joe what “whatever needs to be done” usually consists of.

“Well, fence mending, or else if it’s plowing time you go plowing…planting, hauling manure — that’s always something that you can do.” Joe laughed in an offhand manner. “It’s sort of hard to say, really, because there’s so many days when you sort of…well, you go out an hour after breakfast rather than right after, or something like that. You don’t really fill the day all the way. It depends. In springtime, in planting time, you might go for almost a whole month at six days a week. You hardly take any time off at all. And the same way at harvest time.

For a couple weeks at least, you get up, do the chores, eat breakfast and run for the tractor.

“But, uh, it depends — I guess it depends on the person, too, how relaxed it is. There’s always a lot of work to be done on a farm. I’ve never seen the farm that a guy could sit back and say, ‘Well, today I don’t have anything to do.’ But he might say, ‘Today I’m not going to do anything.’ There’s always fences to be mended or manure to be hauled, and that type of thing. And your buildings need a lot of maintenance. There’s always something to fix. But when there’s nothing that really has to be done, you just take it a little more easy.”

Hear that, sixty-nine percent of America?

Now, I didn’t get into this maliciously. One of my grandfathers was a farmer, and is still in spirit. In fact, if it weren’t for the farmer’s depression of the early 1920’s, and what we like to call The Depression, and my grandfather’s orderly progression into his eighth decade, he might still be culling rocks and produce from 60 acres in West Virginia. As it is, he transferred his interests early on to a 10-acre plot in Wayne County, Ohio, and after dispatching a succession of nameless pigs, chickens, cows, horses, sheep and bees (the encapsulated description of one lifetime), he still manages to got out his beans and beets and the like each spring. In addition, farms and farmers produce some of the better trivia information. Like the introduction to this essay. Or, like the fact that the farmer receives only 2.6 cents for the corn that goes into a 31-cent box of corn flakes (but you all knew they were made out of peanut shells anyway, didn’t you?)

No, I am not interested in giving the trade a black eye with a poll of one. It’s just that I have abiding faith in the human ability to turn the truth of day-before-yesterday into yesterday’s myth and today’s law. By definition, that is the intuitive process.

I am curious that, at a time when the United States seems genuinely to be on the threshold of a leisure society of sorts, we are increasingly throwing up this defense mechanism against it, exhorting each other to go to work. You could hear the predictions in the General Electric Co. exhibit at the 1964 World’s Fair that America was moving toward a time of less work and more free time. That message still spins at you for its base in Tomorrowland at Disneyland in Anaheim, California. Since it is a free exhibit, you would guess that a significant portion of the 10,000,000 annual visitors to Disneyland step inside. But do they listen?

Joe Raber and I talked, once his estimate of a farmer’s hard work was made, about alternatives to work. “I think probably, just speaking for myself, that I’d rather be doing something,” he said. He allowed, later, that it would be “nice” to know that the basic necessities for life could be taken care of without the requirement of a job, although he appended, “I don’t really know what I’d do if I didn’t work.” He might travel, for awhile, he presumed, and he would, he agreed, devote time and energy to, say, the breeding of sheep, if given an economically favorable climate.

My grandfather built this scarecrow. It is Halloween, and no snow yet.

In an attempt to draw an analogy for Joe that would describe his and my future, I swept regally into my favorite Derivations of Women’s Lib verbal essay, in which I skillfully conceal tha fact that I can’t recall any dates or place names while reciting the pertinent facts of one lecture in American Social History, How Technology Helped the Housewife: The fireplace begat the stove begat the oven begat the microwave oven; the vegetable cellar begat the hot-pack canner begat the pressure canner begat Birdseye begat TV dinners; the rock by the stream begat the washboard begat the wringer-washer begat the washer-dryer begat the Laundromat; the twig broom begat the straw broom begat the push sweeper begat the vacuum. Etc. All in a hundred years, give or take. Thus Women’s Lib. And if you think the women are difficult to understand, wait until machines push the men out of the factories. Mens’ Lib.

Joe could understand that. “Even in Amish territory,” he said, “some of them still bake their bread, in winter, but most of them buy it.” He chewed on that for awhile, as we enjoy saying about farmers. “Like you say,” he said, “there is an option. So maybe we’d be better off without all these timesavers.” In case you are still occupied y the image of a stereotypical farmer, and yours in uneducated as well as hard-working, Joe’s is essentially the same solution offered to the technology problem by Arnold Toynbee. That should tell you something about farmers.

Received in New York on November 6., 1972

©1972 David Hamilton

David Hamilton is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from Newsday. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Hamilton, Newsday, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.