Something’s happening here, and, sorry boys, what it is is getting to be exactly clear.

First Manifestation

“…For there are only two kinds of time (time-future being the province of melancholy seers, jocular quacks, and somber religionists promising kingdoms they haven’t the conge to promise): there is time being lived, and that same time as it is relived In the mind five minutes, five years, five centuries later; and because these times are never analagous, the historian (browsing amid his ponderous tomes and dusty parchments and, by comparison with the rest of us, imagining himself a creature of consequentially high purpose) lives the biggest lie of all.”

— A Fan’s Notes, Frederick Exley

“Today the number of young adults, persons 20 to 34 years old, and the number of mature adults, those 45 to 65 is approximately equal. Ten years from now the young adults will outnumber the mature adults by 14 million.”

—Los Angeles Times, in a story assessing the 1970 census.

WASHINGTON, June 10 (AP) — The Labor Department estimates that 3.6 million additional youths aged 16 to 24 will flood into the labor market this sumer, about two-thirds of them looking for summer jobs and the rest for permanent jobs.

This year’s summer influx of youths from school into the labor market is below last year’s peak of four million but will bring the total of 16-to-24-year-olds in the labor force to 22.4 million, about 600,000 more than in 1971, the department said Thursday.

“Each summer the school-age labor force 16 to 24 years old increases sharply as students enter the job market for summer work and as high school and college graduates, who were not in the labor force while attending school, take or look for regular jobs,” the report said.

The Government has appropriated $377.6 million to provide a total of 1.2 million summer jobs for youths this year.

“The largest graduating class in history — an educated army of 816,000 is entering America’s certified credential society and learning to its sorrow that a degree is no guarantee of a suitable job…. A survey of 140 U.S. colleges and universities indicated that between March 1970 and March 1971, job bids for male B.S.s dropped 61%, and a staggering 78% for Ph.D.s. Actual hiring will be down less, probably by 25% at the B.A. level…. Says New York University Chancellor Allan Carter: ‘We have created a graduate education and research establishment in American Universities that is about 30% to 50% larger than we shall effectively use in the 1970s and 1980s.’ This impressive but top-heavy creation is primarily due to Sputnik, which blasted off when the class of 1971 was in second grade.”

— Time, 5/24/71

“If the satellite ring scrapped the planet as the old world of nature, it even more decidedly eliminated the image of the job-holder or the specialist skills of an old ‘hardware’ society. People, individually and collectively, are now totally alienated from their earlier image of themselves. This has happened within a decade. In the Renaissance, it required a century and more to achieve anything comparable in the alteration of the human psychic and social organization.”

— Marshall McLuhan and Barrington Nevitt in The New York Times

“’This town hasn’t changed, but the people have,’ says 73-year-old Reed Henson. ‘The younger generation would like to have the money, but they won’t work. The older ones are loafing out of spite. It’s getting so you couldn’t hire a pie taster in a pie factory.”’

— reported by columnist Charles Bartlett

“Q. Are you saying that a person’s feeling of responsibility has something to do with his concern about getting and holding a job?

A. Yes, indeed. Look at some figures on unemployment in 1970: The unemployment rate for single males was 11.2 percent, while it was only 2.6 percent for those who were married and living with their wives. The unemployment rate for single females was 9 percent, but it was 5 percent for those who were married and living with their husbands. Now, why the disparity between the jobless rate for married and single people? It has little to do with skill, education or expertise. It’s just a matter of responsibility — of supporting a family. If an individual has to work, he works. If he isn’t required to work — if he can live off his family, get unemployment compensation or welfare payments — then for a certain type of person, there’s a strong temptation to take the easy way out.” employment specialist

— Robert O. Snelling in U.S. Niews & World Report

“Most men have but one or two ideas, anyhow, and to these they hang like grim death. “

— Clarence Darrow

“…Poet Allan Ginsburg was once a market researcher, comedian Jackie Mason a rabbi and artist Frank Kleinholtz a lawyer. But in recent years, such radical, voluntary switches have become almost commonplace.”

— reporter Dan Rottenburg in The Wall Street Journal

“The goals of youth prove too shallow to endure for a lifetime.”

— John Gardner

“The trend raises some serious questions about the future of the U.S. economy and indeed U.S. society; what will happen if millions of youths turn against the material reqards and the competitiveness that have motivated so much American progress? For the present, alternative careers appeal primarily to upper- and middle-class students, who tend to take affluence for granted. …A number of radical education experts argue that the U.S. has become an overtrained society, producing too many specialists for too few jobs. Every year more and more people enter colleges or universities; in fact, the number of American students currently exceeds the population of Switzerland. Yet 80% of all jobs available in the U.S. are within the capabilities of those with high school diplomas. …Disconcerting though it may be to parents who have heavily invested in their children’s educations, many of this year’s graduates who are heading for alternative vocations may be on the right track.”

— Time, 5/24/71

Irving Eugene Kaplan, after a dozen years in industrial placement and research, and two years studying “automation”, rated 500 occupations randomly chosen from the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, published by the U.S. Employment Service: 300 entirely replaceable by automation and standardization; 106 entirely prone to obsolescence; 71 partially replaceable by automation; 14 not replaceable by automation, and 9 too unique or small an occupation to require automation. (21,741 titles are listed in the dictionary; using Kaplan’s analysis, 17,653 are readily replaceable, 3,087 could be partially replaced, and 1,001 are resistant to automation.)

— from Committed Spending, A Route to Economic Security, edited by Robert Theobald

“Work is going to become as rare an anesthetic as the most costly and most prohibited drug.”

— Arnold Toynbee

“Computers are getting smarter all the time. Suppose they get to the point where one decided to take control?”

— John Wilkinson, Center for tte Study or Democratic Institutions:

Member of the audience: “That’s easy. All you have to do is pull the plug.” Dr. Edward Little, physicist: “We’re talking about a smart computer. It foresaw this possibility and built a powerful robot which is protecting the plug.”

Second Manifestation

…Before we take this first step, please, would you ask EPICAC what people are for?

“When I got this job, I got into the trip of having to find my own apartment and I got into money things, you know, and it was really security. Like, have you ever seen the film, “The Woman of the Dunes” at all? Well, in the film she lives in this pit where the sand falls all the time. And she says — this man who’s sent down there — she says, ‘What would I do without the sand falling? No one would need me.’ And I began to think of my job as, like, who would I be or where would I be without this job. It’s like the sand falling, you know — no one else to take care of it. That’s the only reason I’m existing. And I could see a lot of people getting into that with their jobs. It’s like a shitty thing, but you keep on doing it because — if you’re not at your office, you know, like the only minute or time that people notice you is when you’re not there.”

Katharine said all of that in describing a year of eight-to-five, her first, which she had just that week quit, apparently (this was left as vague as her surname) at the request of her employer. The job, “photo lab technician” for the state of California, university division, home base San Francisco, was not one she prepared for in college. “I found out what my B.A. meant,” she said. “They wanted to know if I knew all about wires and plumbing, and all the guy I interviewed with wanted to know was who I made it with and stuff like that.”

Katharine is 23 and will take unemployment compensation if she can get it, welfare assistance as a last resort (she shares lodging with three other persons, and “last resort” is when the equity of the “house” falls short), and will avoid another eight-to-five at all cost. “Doing an eight-to-five thing you know, putting myself within a special time space to perform, you know, when I know my energy goes in spurts, it doesn’t go eight hours you know REST then eight hours REST then eight hours — it’s not like that — then I can’t give myself fully.”

Incidentally, Paul…people didn’t pay much attention to this, as you call it, Second Industrial Revolution for quite some time. Atomic energy was hogging the headlines, and everybody talked as though peacetime uses of atomic energy were going to remake the world.

Jinx Junkin is 49. She lives in Santa Fe, N.M. “I’ve been here since 1954,” she said. “I developed terrible, terrible ulcers, and I came out here for six months to get over it, and I said, I don’t care what I do for a living, I’ll do anything for a living, I want to stay out here.”

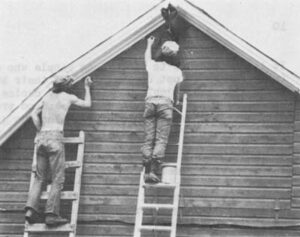

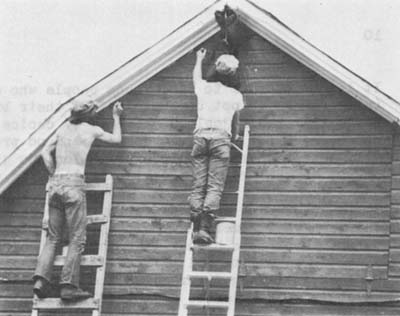

She taught children’s theater and ballroom dancing (“…that was when kids out here hadn’t had any kind of manners training, practically — you’d have little eight-year-olds checking their guns as they came into dancing class…”), acted as poll-watcher, decorated windows, ran a gift shop, bred afghan hounds, clerked, wrote public relations for a state office, performed as an extra in movies, gallery-sat…”I think the funniest job I ever had,” she said, “was, somebody wanted a sign painted on a gable roof, and they said they’d pay $50 for it. So I gathered myself up a starving artist and got out on this roof to paint the sign — and when we got up there, I realized this artist was an alcoholic. She shook like crazy! She just sat there perched like a buzzard on top of this roof while I painted the sign and we each got $25 out of it. I’d certainly never painted a sign in my life, and she didn’t know how to lay it out, but you learned quickly — well, anything and everything that comes along, be willing to do.”

Back in New York in 1954, “…why they thought that I was out of my mind and actually gave me a six months’ leave of absence and said, “You’ll be back.’”

Paul could see the personnel manager pecking out Bud’s code number on a keyboard, and seconds later having the machine deal him seventy-two cards bearing the names of those who did what Bud did for a living — what Bud’s machine now did better. Now, personnel machines all over the country would be reset so as no longer to recognize the job as one suited for men. The combination of holes and nicks that Bud had been to personnel machines would no longer be acceptable. If it were to be slipped into a personnel machine, it would come popping right back out. “They don’t need P-128s anymore.”

Sonny Klingler is 35, has a wife and four kids and a dog that has a dozen pups periodically, two-thirds of an acre in Ashland County, Ohio, and a lot of experience as a welder. From October 1966 until summer 1971 he worked at what is known in those parts as the Cleveland Tank Plant. It was a division of General Motors, charged with delivering up war material to the U.S. Army and others. This is part of Sonny’s story.

“Well, they make army tanks, and — since 1941, I think — and they just quit makin’ ‘em. Over twenty-three hundred employees were layed off over a period of about six weeks. Now they’re shippin’ fixtures up to some place in New York and build ‘em up there. Oh I could go up an get a job, when they get everything set up if I wanted to go up there, but….

“Everybody knew that it was gonna go out, three or four months. And they give everybody a chance that if they wanted to go find another job, well, they could. Go to another General Motors’ plant. I didn’t go to another General Motors’ plant because I was drivin’ a hundred miles a day…and that got to be an old story. Well, we got one plant in Mansfield twenty-nine miles away and one in Elyria that’s thirty-eight miles away and two more in Cleveland that’d been ten miles farther and fifteen miles farther. Mansfield had men layed off and they still do. And, uh, I tried Elyria but they’ve got men layed off. I could have got a job fifteen miles farther than the tank plant, but…for the money…if you figure ten cents a mile like you’re s’posed to, might as well sit home and draw unemployment or sit on a rockin’ chair like a lotta people do an’ draw welfare.”

There are a lot of things that Sonny Klingler can do. He is not lazy, he is not without mechanical aptitude, but he also is not blind. “I heard that the Chevy plant in Cleveland…” he said, “I heard this a week or so ago — that over the next sixteen months or eighteen months that they’re gonna put machines in to replace twelve-hundred guys.”

Paul counted around the table — 27 managers and engineers, the staff of the Ilium works and their wives.

“If I get to the point where I really do bag it, I want to have built my assurance in advance that I represent a talented human being when I return, so that I don’t have to worry about it at all, or think about it very much. To convince others. It’s always easy — I’m fully confident in myself — but i want to make it as easy as possible when I come back, and it’s quite easy if you have some sort of documented history of, uh, fairly nice work.”

Robert Cunningham, 28, out of Lincoln, Nebraska, long enough to graduate Williams College, to fiddle with the machinery in Washington, to collect an M.A. from Princeton University, a Woodrow Wilson scholar, sits in a spare office in Seattle, running the show for powers that be in Stanford University and D.C. who want to know in specific and sociological terms the effects of a negative income tax on people’s motivation to work. Paradoxically, at the point in time when he recognizes that he could sail at or near the top of the Bureau of the Budget, a bureaucracy he admires, Robert is planning to sail around the world.

“So what’s going to happen, I guess,” he said, “is, let’s say I get a boat a year from now, in the fall, spend four or five months testing it out, running it a lot, putting in extra water tanks and…getting it really ocean worthy. Uh, by that time I will have been able to say to myself as well as say on paper, or for God and country, that, uh, okay, I’ve done a good job, I’ve left the project in good shape, I have prepared someone to follow up after me….”

Say now, this is one of these here “dropouts” we’ve been hearing about, these “executive dropouts”? Not exactly. No matter how hard some people wish it, as long as there’s a show to run, somebody is going to volunteer to run it. “I guess the funny thing is,” Robert Cunningham, prospective world sailor, said, “is I’m still a very ambitious person. And, uh, no matter what I do or for how long I bag it, when I come back — at least right now I think — that I will still be interested in some rather, standard, professional…occupation.”

…In hundreds of Iliums all over America, managers and engineers learned to get along without their men and women…production with almost no manpower.

Irene has just moved into the house on the Haight in San Francisco that includes Katharine, and has the same ambivilance about surnames. She is almost 25, and has just left a teaching career (two years elementary, one year youth director at a YMCA) with enough savings to get by on for awhile. She is not thinking in terms of time, though, nor in terms of that money, nor in light of the fact that jobs are drying up in her profession. “I’m taking it day by day,” she said, “and just how my feelings flow”.

“I quit because I felt that there were a lot of things in my life that I just hadn’t done yet, a lot of things that I had to learn, lot of things that I have to do…and I want to have time to do them. I’ve never had free time. It’s my first free time. I’m looking forward to — wow, there are so many things I have to learn to do. Time to, uh, sew, and I want to have time to draw I want to have time to write and I want to have time to…anything…plants, cooking, baking. I just have an endless amount of things that I want to do. I’m just opening to, to, to learning and seeing and hearing and…and touching and, it’s like awakening all of my senses, for the first time. I’m getting off on all the free time I’m going to have.”

There were a few men in Homestead — like this bartender, the police and firemen, professional athletes, cab drivers, specially skilled artisans — who hadn’t been displaced by machines. They lived among those who had been displaced, but they were aloof and often rude and overbearing with the mass. They felt a camaraderie with the engineers and managers across the river, a feeling that wasn’t, incidentally, reciprocated.

“I’ve done everything, you know? I’m a licensed electrician, uh, master electrician, a licensed plumber, a licensed gas fitter. Somebody’d say, ‘Hey, can you do that?‘ ‘Sure, I can do that.’

“See, when I was 14 years old, I, uh, well, I helped somebody wire an amphitheater, for sound and electricity, and worked on a maintenance crew, and fixed plumbing, and unstuffed shit outta toilets, you know…so, uh, I just, you know, you just look at somethin’ once an’ you know how to do it, it’s just a question how bad you wanna do it. I could probably invented the carburetor or somethin’ like that if I really wanted to, you know what I mean? — or invented anything. All you got to do is want to do it bad enough, and be careful. An’ I do good work anyway, man. People will, people will wait months for me to show up — at ten dollars an hour, you know? Just ‘cause they know I care.”

The speaker is Don Gellard, 27, five or six years out of California, Wisconsin and points East, who is building houses in Santa Fe instead of tending a drug store. That is what he thought he would do eleven years ago when he left high school early to go to college. “Be a pharmacist,,” he said. “They make a lot of money. It was just a shuck, you know? When I went to college, man, I thought that the professors wore them flat black hats, you know, with the thing hangin’ down, an’ robes an’ had grey beards. Honest to God, that’s what I thought. I kept lookin’ around for ‘em, you know? Somebody handed me a reefer, and, uh, my entire life changed.”

Between college and carpentry, he ran a 350-seat restaurant in Madison, Wis., and sold (or tried to: “I don’t remember if I ever sold anything.”) high purity, rare earth metals, $2,000 a pound, in California. One day about three years ago, he packed it in and split for the mountains. Lately, he’s been moving back out, acquiring New Mexico state licenses that verify his skills.

We talked one day, he somewhat reluctantly, about a point in time when machines will be the most diligent, and dominent, workers. He said:

On the fate of the workers. “That’s the dues they gotta pay, man. They’re not gonna get a taste of the, uh, great beyond this time through, no matter what happens. I honest to God do not have faith in the, uh, corporate consciousness of the human race as it stands today. There’s a great deal of individual suffering gonna have to happen, man, the suffering is too disgusting to think about. But there’s too many people on the earth, man, there’s too many blue babies have been saved, there’s too many fucking — children been born that should have died, you know, as cold and, and, and as frosty as that may seem, there’s too many people on the earth, and most of them are biologically unfit — and I may be one of ‘em. If the doctor hadn’t kicked me in the ass, maybe I wouldn’t of made it — and all the better for the world. One less mouth to feed, one less person breathing carbon dioxide into the air, one less — two less cars polluting, you know? It’s just…it’s overpopulated and someone’s gonna have to die, man. And — there will be a great amount of suffering. But it’ll be over in short order, in, in the scheme of the whole thing. And maybe that’s too fucking uh, uh, too heavy for anyone to be able to code into a computer t’be able t’figure out what t’do with all the people who are outta work.”

On the other half. “How can I say that people are dumb? It’s not that they’re innately dumb, it’s just that they’ve been uneducated…or deeducated. You send a child, man, who is totally open, man, who has a completely photographic memory, you know, and has immediate contact with the great beyond ‘cause he was just there, you know, and you send him to fucking public school and you make him sit down when he wants to run and you make him read when he wants to write and you make him write when he wants to do arithmetic and pretty soon you end up with a totally fucked up individual, you know? Well, maybe not totally — most of us went through that system and by the grace of God got back some kind of strength, and intelligence, and insight. But, uh, that’s why they’re stupid, man.”

On his role: “How do you teach somebody out of the depression to give it all up, you know, and let it all hang out? They can’t do that. Like, I can’t even talk to those people. Like, I can be friendly and talk, you know, like, ‘Hi, nice day and yes, good job, Don, blah blah’ …Soon as you get down to somethin’ heavy, it’s like, you know, they just don’t understand my English. And I don’t understand theirs. I don’t know, man, if I came upon someone in the street, I’d take ‘im home an’ feed ‘im. I’m gonna help as many people as I can.”

On solutions: “Well, let ‘em shit outside and have no running water in their house and bust their hump like I do. Right. You gotta take the bruises, man. You can’t cruise in on anyone else’s knowledge. That has been my experience.”

It’s beginning to look like a problem nationwise, not just Iliumwise.

Young “dropouts” usually have the same answer to the question “What did your parents think when you quit?” “Oh, they just couldn’t understand it.” With David Gaines, who is 58, the coin is flipped. The youngest of his three children is 23. “They seem to be very encouraging,” he said.

Three years ago, children gone and a marriage too for some time, David Gaines walked away from the press building in Washington, D.C., from producing educational and religious films, to the theater. “It just all developed, I think,” he said. “There wasn’t any big talking myself into it. It was mostly in pursuit of this theater hobby, um, urge, or whatever you want to call it. It seems to me that as I was doing that last nine-to-five job in Washington, I began to see quite clearly that this great interest was all that was important…and making money for the sake of making money — or a higher standard of living — wasn’t.”

He has a litany of odd jobs to his credit by now — carpentering, tending art galleries, driving a school bus, housecleaning — and, due to a recent, unexpected inheritance, a stable, new life as a modest landlord in Santa Fe.

When David Gaines talks of working and not working, he offers the perspective of having been a professional in both armies — and something that his contemporaries in the dropout generation usually don’t have, age. He can remember when the five-day week caused a fuss. “Sure, ‘The world is going to pieces!’ ‘Grass will grow in the streets!’ ‘Nobody’s going to work on Saturdays, two-day weekend….”

He resists the term “dropping out.” “They’re just moving with the way things are,” he said. “It’s a natural development, in my mind. The depression defines me — people my age — much more than World War II. I was, in 1929, the crash, I was 15. It was a spectre, and, um, I think people of any economic situation at that time — this was the forming thing in their lives. It is new — in the sense that the spectre isn’t there — that people are electing to drop out. They’re not forced to. The security thing is the difference, obviously. Um, most people my age still have this ingrained fear…and this is what the young don’t seem to have, this fear of want. To me it looks productive, it looks positive.”

…Halyard was explaining that the house and contents and care were all paid for by regular deductions from Edgar’s R&RC pay check, along with premiums on his combination health, life and old age security insurance, and that the furnishings and equipment were replaced from time to time with newer models as Edgar — or the payroll machines, rather — completed payments on the old ones. “He has a complete security package,” said Halyard. “His standard of living is constantly rising, and he and the country at large are protected from the old economic ups and downs by the orderly, predictable consumer habits the payroll machines give him.

Sonny Klingler, sixty-five miles away from a welding job when the tank plant closed, sat down. “Well, I drawed severence pay for a year, well, forty-eight weeks. Now I could have went out the next day and got a job…but I was tired and wore out — I been in the hospital quite a few times — and just thought I’d rest awhile.” At work, he grossed a $130 weekly pay check. On severence: “See, I was bringin’ home $125, but they didn’t take any taxes out, and…I didn’t have to buy ten dollars worth of gas a week, for the car, and uh, I had free hospitalization and life insurance…for a year.”

It is not unusual to find young people who do not work turning down welfare (although it is not unusual to find their brethren accepting it, either) on the basis that their jobless state is by choice, and the government subsidy should be reserved for those with no job and no prospects. Yet, these same persons will accept unemployment compensation, no questions asked. It is expressed often, as the program’s design implies, as an “earned” right.

State government and employer pay “insurance” for twenty-six weeks, with a thirteen-week “emergency” extension readily available. And, in states with an unemployment rate higher than the national figure, the federal government will cough up an additional thirteen-week “emergency” coverage, as much as (depending on cost-of-living figures) Connecticut’s $58. That is one year’s freedom for anyone with a moderate budget and the inclination to stay put.

“What does that mean?” said Paul. The sergeant looked at the pile without interest. “Potential saboteurs.” “…What right have they got to say that about me?” “Oh, they know, they know,” said the sergeant. “They’ve been around. They do that with anybody who’s got more’n four years of college and no job.”

Don Gellard, behind his mask of arrogance, has something to say. “I’m doin’ this bullshit, man, cause I think it makes more sense to me — ‘course it does, otherwise I wouldn’t be doin’ it — to build houses, ‘cause people need houses, you know? People basically need shelter and sanitation facilities, you know, and I know how to do that, and I know solar heat and, uh, convection radiant heat, uh, and losa stuff, you know?, lotsa biotechnically meaningful things. Uh, building a car is not biotechnically meaningful at all. Nor are most other things, you know?”

Robert Cunningham, preparing to escape back to his spare office and statistics on negative income tax, talks about an excess labor force. “Herbert Gans had one of those popular articles in The New York Times Magazineawhile ago, one of those semi-essays, and his point was that government has two choices: They either make sure that everyone is employed — and hopefully in jobs that aren’t makeshift jobs — or government bribes people to work, uh, by paying them a guaranteed income. Now, he put it in the negative — that government would have to bribe people not to work. I think that the next…semi-generation…below ours, 24-year-olds on down, aren’t gonna have to be bribed not to work in normal occupations.

“We probably have to become more labor intensive again. If there is a choice between capital-intensive and labor-intensive efforts, maybe what we have to do is sort of think about more labor-intensive efforts — except that the normal labor-intensive occupations that come to mind are all…custodial occupations — cleaning the streets of New York City with push brooms instead of big sweepers. Although there are nicer versions of that — they’re having increasingly larger groups of people who annually clean up riverbanks. Maybe the whole environmental industry could be a new service industry.”

Rick Bowers, who is 28, a father, Princeton, M.A., innovator of a prisoner-initiative therapy program for the State of Massachusetts, and two days on the road from that prison job, talks about people who don’t work. “Well, my feeling is that there needs to be a redefinition of what is work and what isn’t. I can think of two reasons to work: One, in a very personal sense, for personal gain, personal satisfaction, and two, in a sort of evolutionary sense, you’re working to better the world or in some way to contribute to progress or evolution. I’d like to see people redefine that second goal of work.

“What I’m talking about is, I don’t see much progress or evolution as far as people are concerned. People are still hassling through the same kinds of communications problems, the same ego problems and so forth, defense, territoriality problems, like they’ve been doing for the last two thousand years. There’s been no progress there. And, like, I’d like to see people go through a lot of personal work — they don’t have to be earning money, they don’t have to be going to a job — but a lot of internal study and personal growth. And to me that’s work.”

Peter Whitehead, 25, a farmer by choice (“The only reason I went to college was, um, I was expected to go to college, right?”) in Vermont: “In a funny way I think I’m tied into the work ethic, you know?, but, uh, I’ve sort of gone a full circle, you know? I, uh, I’ve worked a lot in my life, okay, to have money, you know?, so I could do some of the things that I wanted, all right? Like I’d work so I could have enough money to road race, right?, shit like that. Right now there are things I want to do, you know?, or the work I’m doing I really like, okay?, so I work very hard, so in that sense, you know, I’m sort of tied into it. But, um…at least I think about it myself, you know, that I’ve come into it from a different way.

“Farming is like a career and a committment to a mode of living. In other words what I did is, rather than go out — at least this is the way I see it — is rather than go out with the idea that, that I want to make money, okay?, and look for a job, I went out looking for something that I wanted to do, and I found something that I want to do, and, you know?, and it so happens that I make money at it, sort of, you know? And, like, I think that’s a, really a big difference in this society. I think most people go out looking for money, you know?, and rarely find themselves doing something that they want to do, right? More and more people are chucking it, if they possibly can, they’re chucking it.”

Katharine and Irene, trapped in the same interview, compare notes in an aside.

I — Uh … my mother asked me last week on the telephone if I, um, if I had started looking for a job.

K — Oh, I get that every week.

I — You know, they’ve got the conception of my working and raising a nice little family, and, uh

K— ‘I have to have a skill, ‘cause if my husband dies, you know, I’ll have to be able to work.’

I — Right, right. You know, we were brought up in the affluent time, the time when money was really flowing….

K — And they worked to give us all that and they don’t understand that they’ve given us all that and now we don’t want it.

I — Right.

K — And that’s really a hard trip for them. That’s why, in breaking it to them, you know, like, I’m not going to look for a job, you know, they can’t handle that because they want me secure, they want me to have things, lots of things. They want to know, what do you need?, and what I need is time, lots of time.

I — Tell them a blender, they’ll understand that.

K — They’re sending me one.

David Gaines: “I have a theory I call the ‘Cleopatra Theory’ If I may expound, and it’s so silly, but it has bearing. I have a belief that everybody’s got to have a crack at luxuries. Everybody’s got to have everything before they appreciate nothing. I call it the ‘Cleopatra Theory’: I remember going into a Sears in Minneapolis, when we lived there, and the clerk, the girl behind the fertilizer desk, the garden section, was dressed up as Cleopatra would have been — the hairdo, jewelry, rayon dress — Cleopatra would have envied her, the fingernails, all this business. All right. How’s it going to happen? Well, we’re going through it now. Gradually, it seems to me, through industrialization, everybody gets a crack at it, little by little. In other words, the materialistic society is important — in terms of getting beyond it. Resources are unlimited, in terms of outer space. Sure, we have limited resources, limited atmosphere and so forth, but we live in a universe that is limitless. Now, in a thousand years, I’m sure, the Russians won’t be wanting automobiles. It’s all relative.”

Mal Karman moved to San Francisco two-and-a-half years ago. “When I started freelancing, I fully intended that it would be like for three months, and that I would, uh, I’d be doing some hustling in that time and that I’d also write a novel in that time. Well, what happened was that three months, on all counts, became two-and-a-half years.”

He left five years’ experience as a reporter on a newspaper in the East, and, with his girlfriend, followed Greeley’s dictum to the limit. “We lived in a townhouse apartment in Diamond Heights, which is one of the nicer sections of the city. We had a balcony that had a view of the San Francisco skyline, and we had a swimming pool … and, uh, we were splitting up. I got myself a nice, uh, bachelor pad for a hundred and a half, which didn’t seem like a hell of a lot compared to the two-ten that I had been paying, but still, I didn’t have the income that I had had.

“I was working hard, writing stuff that I didn’t particularly like writing, and eventually I decided to stop working out all that rent and busting my chops doing articles I didn’t particularly like doing. So I got together with some friends and we rented a place on Oak Street and my rent came to $42.50 a. month. Which meant that I could practically do nothing and get by. I had independence.” Sounds, figuratively, like a slide from Nob Hill to the Haight. “Figuratively?” Mal Karman said. “It’s almost literally!”’

Sonny Clingler, who didn’t look for a job until forty-six of his forty-eight weeks off were gone, talks about his days at home. “Oh, I worked around the house, an’ helped a few of my friends, did some work for my sister an’ stuff like that. I didn’t sit around much. Uh, I didn’t really have too much money to, you know, do anything. Even $125 a week when you’ve got a $128 house payment an’ a $80 car payment, you don’t save too much with four kids.”

Back in 1954, when people thought you were crazy to chuck it, Jinx Junkin “struggled mightily” with Santa Fe. “We ate beans. It was fine in this community, because everybody — whoever had a job or whoever had any money would put in a pot of beans and everybody would go. In Santa Fe there’s a tremendous warmth and generosity. If anybody ever sees anybody hungry, they always take them home. And that certainly was well-established when I got here in the Fifties. It’s never ended as far as I know.”

The music stopped abruptly, with the air of having delivered exactly five cents worth.

— (This and other indented material excerpted, entirely innocent of context, from Player Piano, a novel by Kurt Vonnegut Jr., published in 1952 when he was considered a science fiction writer.

Received in New York on January 10, 1973.

©1973 David Hamilton

David Hamilton is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from Newsday. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Hamilton, Newsday, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation,