“This place is full of willing people — some willing to work and the rest willing to let them.”

— counter sign in a Manhattan Hamburger Haven

Joel Horowitz, City Mouse, glues himself to the window of Katz’s Delicatessen and waits out the rain.

He is out on a Wednesday to check his routes, and, unless an all-day downpour is forecast or he has switched to night cycle, he is out today. Nine-thirty breakfast, on the street by 10; up Fifth Avenue to Central Park and back down Second to 21st Street by five, in time for three hours of basketball. Home by 9:30, dinner, maybe TV or the radio, a newspaper; to bed at 1 AM.

The City Mouse is getting about as close to being a cipher as he can get: Most of the statisticians have lost him. He used to work, but now he doesn’t. He used to get workman’s compensation, but now he doesn’t. If one institution of higher learning lists him as a college dropout, three do (and that would make him a false statistic). If he is unlucky, he’ll step on a traffic counter today; luckier, they won’t find him until he makes the cemetery.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics, Middle Atlantic Regional Office, has estimated that its number-gatherers are missing as many bodies as they are called upon to count in New York poverty pockets: If 25,000 blacks and Puerto Ricans are listed as “unemployed”, in Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant and the South Bronx, 25,000 are not counted. The City Mouse is neither black nor Puerto Rican, but he fits the category, in Labor Statistics’ parlance, “the working age nonparticipant.”

Joel Horowitz unglues himself from Katz’s and walks west on Houston, headed vaguely for Fifth Avenue. The rain has stopped. “When I look in the want ads for a job,” he says, “I look under ‘C’ for ‘Clerical, and ‘G’ for ‘Good’. And there’s never anything under ‘G’. I don’t know many people who enjoy their work.”

He details his work history: “Five months for the Post Office in 1966 and five months again last year.” Not much to show for 25 years. “At an early age I saw that work was something to be avoided. Why? I looked at my father. What did it get him?” Joel’s father is a garment cutter. Joel’s mother has gone to work within the last six months. Until two years ago, the family lived in a larger home in Queens. The move to Manhattan’s Lower East Side cramped quarters, even though an older brother left the fold. He works. A younger sister is in school, training for a secretarial job.

“The first time,” Joel says of his work experience, “I had dropped out of school and was just hangin’ around, so I decided to get some money. The pay ($110 a week) wasn’t bad for me, ‘cause I don’t need much money. Before that…I’ve been goin’ to school for parts of eight years. I felt no need to work during that time, ‘cause I was living at home and my parents took care of expenses.” He debates with himself, then makes a confession.

“I’d drop out ‘cause it was just too boring,” he says of schools, detailing credits won and lost at Brooklyn College, New York Community College and the City University of New York, “but it was related to other psychological factors — why I didn’t go to school.” He relates a tale of compulsive gambling, on sporting events, which involves running afoul of bookies, being rescued by his father, gambling away friends’ money. “I lost most of the money I made at the Post Office,” he says.

“It’s a sickness. I haven’t gambled for a year because I haven’t had the money — I won’t have until I get my income tax refund. The whole thing is silly: I’d have nothing else to do so I’d gamble — but the difference between winning and losing, it’s nothing. I’m fairly confident I won’t get back into it. But I won’t be sure until I get a job and have some money.”

While gambling was helping stall his education, other factors were complicating the easy life of Joel Horowitz. The move to Manhattan meant sleeping on the couch; he’s the family member without a bedroom. “I took the second Post Office job to get an apartment away from home,” he says, “but I gambled the money away.” Meanwhile, the statute of limitations on his free tuition to city colleges ran out. “So I’ll have to pay if I go back to school,” he says. “I’m determined to move out of the house (If I had my own room I wouldn’t move), so I’ll have to work and go to school. But that would be a 180 degree turn from now; I’m not sure I could lead a disciplined life.

“The pressure to get a job is not so great as you might think. I have the typical ‘Jewish mother’ — you know, ‘Wear you rubbers’ and chicken soup, but she knows any job I could get is going to be boring. I feel kind of stupid, taking orders from someone I don’t respect. But the only job I’m qualified for is clerk. I could go along like this without my parents objecting.

“I get my food and five or six bucks a week — just what I can chisel from my parents to eat out or go to the movies or for carfare when I go to see friends — and that’s all I need. I’ve never been into material things. One thing — I don’t need money. If I earned $30,OOO a year, I’d only work one year out of six.

You get the feeling, walking up Fifth Avenue with the City Mouse, that one day he’ll do something. This is a phase, a period, something to get through: atrophied adolescence. Joel Horowitz, himself, is not so sure. “I never had an objective,” he says, “even during college. ‘What am I doing here?’ I’d say. ‘Well, it’s just part of the progression.’ Ideally, I’d like to just hang out, but….

“I can’t imagine a job I would find satisfying. They’re either boring or you end up taking orders from someone you don’t respect. Oh, sure, I could imagine myself finding a cure for cancer, but that’s a fantasy, that takes skills I haven’t got.” He pauses, smiles. “I’d like to replace Willy Mays in center field.” He pauses, smiles. “But I better give him a few more years.

“If I did go to college,” he says, “I guess I’d teach. At least that’s what my friends who went to college are doing.”

Joel Horowitz, who hasn’t yet finished college, does the following: “Now that we’re in the warmer season, I’m out of the house at 10. I usually walk around the city, usually I have the same routes, like Fifth Avenue to the Park and then walk around or sit around. Sometimes I have a newspaper with me. Sometimes I go to the movies on 42nd Street. If you go early enough, you get in for 85 cents. I try to get down to 21st by 5 to play ball until 8. Then I stay out ‘til about 9:30. I usually eat dinner at 9:30, but not with the family — we never had that in my family. I read the paper, watch TV, listen to the radio. I go to bed at 1 AM.

“Most of the time I spend walking — thinking, looking at people. I don’t talk to people, though. The last few months I’ve been preoccupied with what my next action should be — what I should do.”

When he feels like it, Joel swings over to the night cycle. “I stay up ‘til 6 AM and then sleep ‘till 4. For the past six months my mother’s been working, I can do it. Before, she was always around.” Sleeping on the couch during housekeeping is not recommended. “My schedule is pretty rigid. I get up at 4 because I know I’m supposed to, go outside ‘til about 10 or so. From 1 ‘til 6 I listen to the radio — some music, some conversation.

“I don’t read a lot — papers, magazines, but not books. The actual procedure of reading a book, my eyes get tired. It’s uncomfortable, the position you sit in to read a book. I don’t think much good comes of it. You can’t learn that way — unless you feel that knowledge is a good in itself. I’m not so sure, myself.

“I keep up to date; I’m interested in politics. I guess I would be liberal, but some of my positions would coincide with the conservatives’: like busing; it just doesn’t solve anything. But I wouldn’t vote. One vote doesn’t mean anything.”

A question begs itself: Joel, if all you do all day is nothing, why not change the arena; take zero on the road? “I could never go out. It’s too difficult to survive; you have to be an extrovert…If I got in a tough situation, I’d feel like running home. And you either have to work or go on the bum.” Yes.

“I do think that there are people who are envious of me. They resent their jobs. One of my friends asked me, ‘Don’t you feel foolish, takin’ money from your parents?’ I asked him, ‘Don’t you feel foolish takin’ money from First National?’ They’re paying him $145 a week for doin’ nothin’.”

We’re so sorry, Uncle Albert,

But we haven’t done a bloody thing all day.

We’re so sorry, Uncle Albert,

But the kettle’s on the boil

and we’re so easily called away.

— Paul and Linda McCartney

John Miller (not his real name), 24, Country Mouse, points to the field at his right. “See it?” he says. “It” is a woodchuck, standing on a stump 200 yards away looking at us. John’s eyes are quicker than the dogs’, and the guess is that he has seen the ‘chuck sooner than he would sight an empty cab on the Avenue of the Americas.

“The city?” he says. “No. Never. I don’t want to be there when the big wave rolls in. They’ll all go down, in their own shit. The city is a bad trip.” As an alternative, for the last six months he has lived on a rented 65-acre farm near Gilsum, N.H., that he and seven others who live there call “North Winds,” a commune. For more than a year before that, he lived with a group on Long Island. In that period, approximately 20 months, he has held a job for all of two weeks.

That doesn’t mean he hasn’t worked; it’s just that the work has been on his terms. “A job,” he says, “is punching in and punching out. Anything you don’t have to punch in is not a job.” On Long Island, he supplemented the group’s income by helping rebuild Volkswagon camper buses and selling them; at Gilsum, the group hopes to sugar for maple syrup, do sustinence farming and perhaps breed horses. John paints a peach and leaf pastel with his aspirations, but reality at North Winds may come in darker shades. It is not clear just who among the eight (ranging in age from 19 to 24) knows how to fence a horse pasture, or how much fencing costs; or who knows what equipment is needed to establish a sugaring business, or where money for it would come from. What is clear, though, is that they are willing to work at this alternative to work.

“Some people need to work,” John says. “Oh, I needed it for awhile. You always got…some people are always worrying about something, you know — in other words, takin’ care of business and shit. Like my mother. Somehow you say to yourself, ‘God, I don’t need this shit anymore.

“It’s a big thing to quit work, you know, big security thing. I was planning on going to California, ‘cause I had my shit together — I had a car and I was makin’ a coupla bucks. I was drivin’ truck; I wasn’t savin’ anything. But I was getting’ $475 for my Volkswagon and I was gonna pay a month’s rent and that would leave me with $400. Ijust got into layin’ around. Not needin’ money for pleasure anymore. And that’s where it’s at.

“I just don’t need things. You don’t really need money — just a place and a house. That’s our whole scene. Like if we were to have this place for five years, somebody could always chip around for awhile, and, you know, they’d always have a place to come home to.” One commune member currently is “chipping around” with the Keene, N.H., highway department; another, John’s cohabitant, receives unemployment. Their money is the group’s total income, excluding savings accounts.

John’s disassociation with money is nearly complete. Budget? “I don’t know,” he says. “I wouldn’t get into figurin’, but, uh, it’s just basics — just rent and food. This year’s strictly been Karen’s unemployment, $53 a week.” (Karen somehow has managed to get two 13-week extensions on her 26 week unemployment benefits; no one knows why and no one is asking.) “A lotta people are still money oriented,” John says, excluding himself from this group. “It’s (meaning finances) easy to do individually. Like, you know, Karen pays for rent and food and, uh, you know, I just put up some good energy workin’ around the house and shit like that. I’d go out to pick up a coupla bucks if I had to, but I haven’t really needed to.”

The one time that he did was the result of what John calls a “money hassle” (“I hate money hassles.”) with another member of the group over borrowed funds. John and Karen moved out and he took a job in Keene, operating a hole saw for a firm that manufactures souvenir pine buckets, intending to work for six months and save, he says, the.purchase price of a farm. He stayed two weeks. “I’d come home irritable and shit like that, you know. It was easy to quit.” He paid off his debts, moved back into the group, and never gave a second thought to his own farm. “Work — it’s useless.”

How John arrived at that conclusion is difficult to trace; for him, impossible. He remembers no impressions of his father, an airlines executive, at work, except for visits to the office: “It was a drag. You had to dress up.” He seems to have the impression that his parents value their material possessions more than they value their four children. John was a grade school dropout, hiding in the closet until the school bus had departed. Like his older brother, he left school before graduation (“I think it was 10th grade.”), but like his brother, earned an equivalency diploma with little stress. “It cost me six dollars,” he says, laughing. “I have a high school equivalency diploma, but that doesn’t mean shit to a tree.”

Three years in the Army, Germany and Vietnam (“I think it’s okay when I look back on it. I drove an armored personnel carrier and I bitched a lot. It’s okay. I did it.”). “So I came back…and got swallowed up in the establishment. I was scared. I hung out about two weeks. That was my vacation. Then my parents made me get a job. I worked in lumber yards, dollar-fifty-an-hour bullshit like that. I did that for about three years. Then I was awakened.” He drips irony into that last sentence.

Before the Army, John worked with horses, even thought seriously about training to become a jockey. After, he drove truck, worked in lumber yards, crewed national moving vans. Ile was tossed off a van once in California for misbehavior of some sort, fought with fellow workers in the lumber yards; work “punching in”, was seldom pleasant.

Now. “I try to meditate, you know, and like, it really relaxes you, and, like, there are no bad thoughts in me for a week. Even when I’m down at my parents’ house. I just can’t get myself aggravated. Factory work, you know, bullshit work, white collar work — you know I couldn’t do that, sittin’ in an office, I couldn’t do that. I’d wanna be outside, you know, like maybe on a horse farm. At night, I want my body to be tired, not my mind, you know. If I could be my own boss, like, maybe now I could be raising horses on a farm. I wouldn’t wanna ask for anything more — I wouldn’t hassle chicks, I wouldn’t hassle over cars, I know I wouldn’t. Then people would come and say, ‘This guy’s doin’ his trip, but it’s not my trip.’ You know, I wouldn’t wanna drag people into my trip — that’s what it’s like. If I really have a thing where I can do what I really want to, I don’t have to worry about other people.”

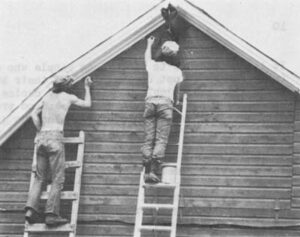

John’s “good energy around the house” includes building chicken coops, rehanging doors, repairing plaster and wallboard, cutting firewood, working the garden, and “Throwin’ off a lotta good energy.” He sews a birchbark envelope for a letter to his sister; he walks the commune’s 13 dogs while meditating. This winter, he crafted a pair of snow shoes, imperfect, but passable. He has devised a spinning scarecrow, black on one half, white on the other, for the garden. Sometimes everyone smokes up. (“Well, I did psychedelics, mescaline, acid, grass, stuff like that for awhile,” John says. “It’s a drag. You get wasted. I snorted some heroin; I don’t dig it. Speed, you know. It’s cool. I did coke three times, never got off, never had any good coke. I wouldn’t do it now. ‘S’nothing like a jay, you know — like, if you earn a jay or somethin’ so that you can, you know…get high.”)

John is not particularly speculative about his condition. “If everybody didn’t work,” he says, “everybody’d be, oh, they’d probably be a hell of a lot better people…at this level. I don’t know what the government would think — I’ve never been into politics. (I just don’t want to get involved. Oh, we were gonna register, we got into this long rap, like the only way we’re gonna stop all this shit is to vote. Sixty percent of the people that can vote, you know, just sit around on their ass, you know, and get high, and shit like that, when they really could be, you know, be voting and stopping it. That’s the whole solution right there. But that’s as far as we got, you know, talkin, about it.

“If I thought I had something to vote for — you know, if I had a farm with a five-year lease or something like that — that’s like a life, you know? It’s worth voting, you know, to keep in a small town — to keep a big road from goin’ through your farm — or to stop it from getting bigger. But if you’re just bummin’ around, travelin’, you don’t give a shit, you know, you just pick up and move to another country scene.

“Well, I probably could go on the rest of my life like this. I just wanna work for what I want.”

We have returned, from the fields and the woodchucks, to the house by this time. The radio is on. “David”, a disc jockey for CHOM-FM, Montreal, is into some huge rap about how social scientists, unnamed, are predicting that sometime soon 10 percent of the population — and technology — will do the work for all of it. John, apparently, doesn’t notice. “I just want a place, you know, with a bunch of people, you know, just gettin’ close to nature,” he says.

“Hard times were when hitchhikers were willing to go either way.”

— Farmer’s Almanac, 1972

Received in New York on June 19, 1972

©1972 David Hamilton

David Hamilton is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from Newsday. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Hamilton, Newsday, and The Alicia Patterson Fund.