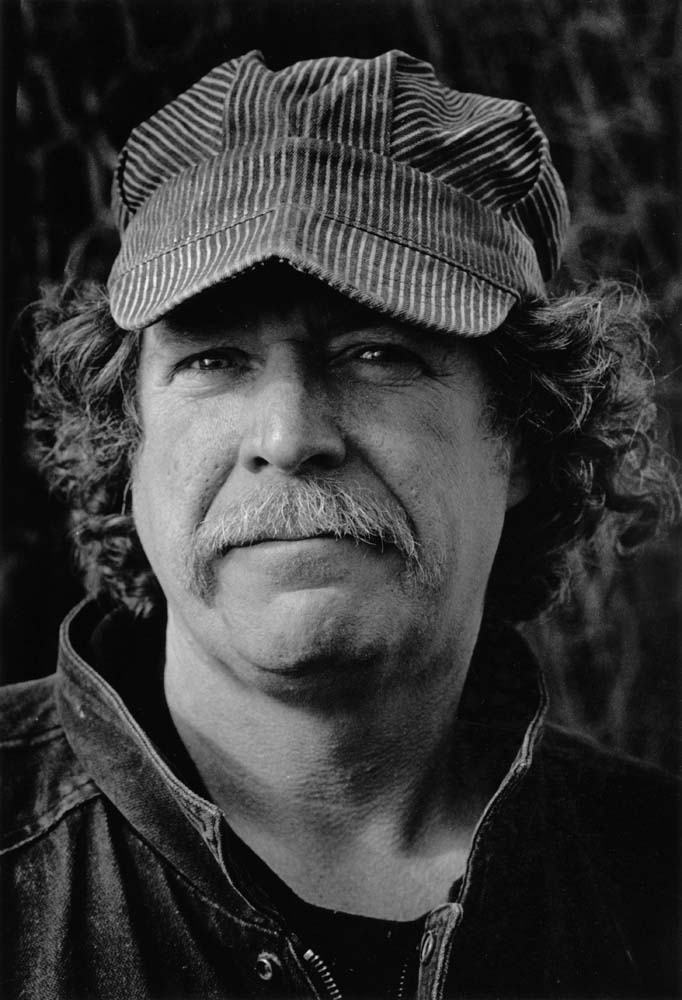

The crew of the fishing boat Edward L. Moore out of Portland, Maine.

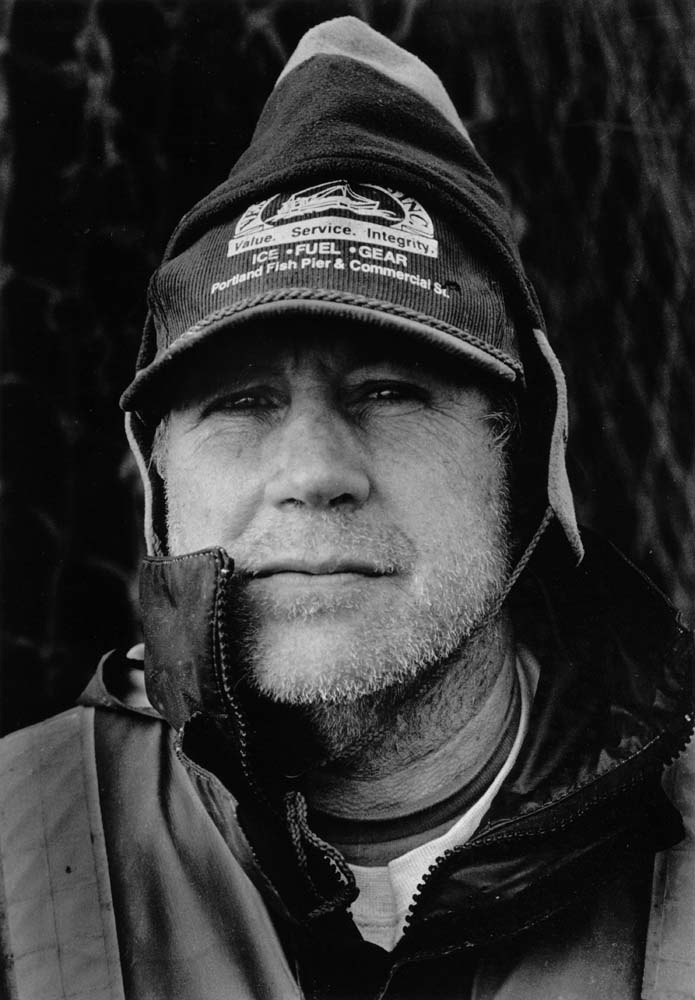

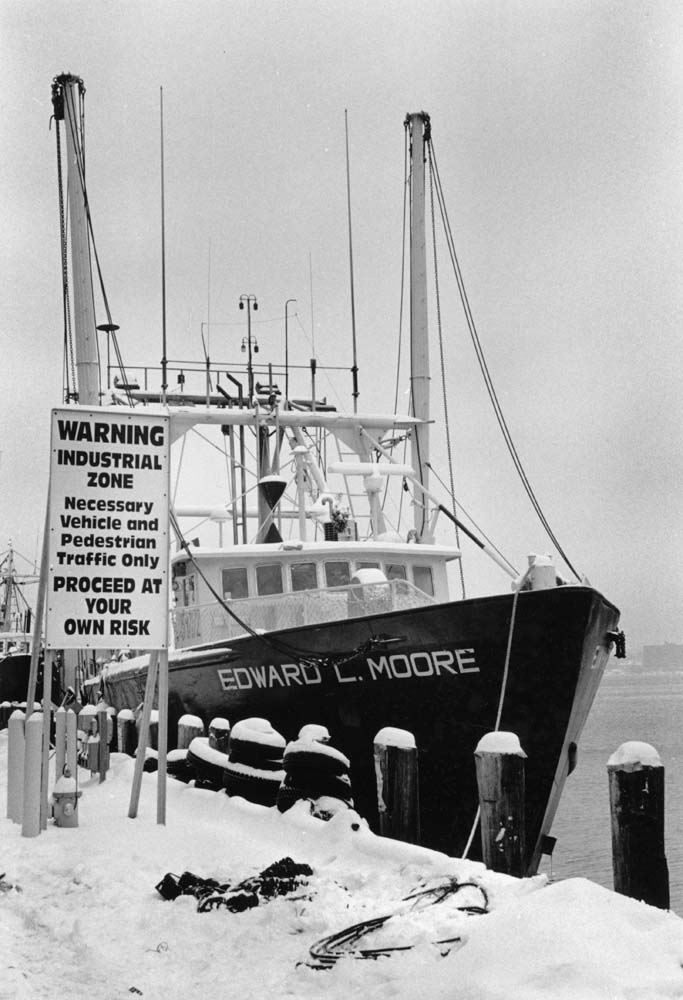

Thursday, December 14 — By early this morning the snow has blown deep drifts across the steel deck of the Edward L. Moore (ELM), an 87’ stern trawler tied snugly in her berth at the Fish Pier in Portland, ME. It has been nearly six weeks since Scott “Scotty” Russell, 45, brought back the largest ground fish catch in his nineteen years as captain. On the same fishing trip he discovered a serious leak around the rudder post of the vessel.

Larger commercial fishing boats like the Edward L. Moore can make trips in foul weather when smaller craft must stay in port. Usually higher prices are obtained for the catch at auction when the going gets too rough for much of the competition. Three fishermen died on December 14, 2000, the day this photograph was taken. Their 35’ mussel dragging boat was swamped by several waves, about eighty miles to the northeast of Portland, near Jonesport, ME.

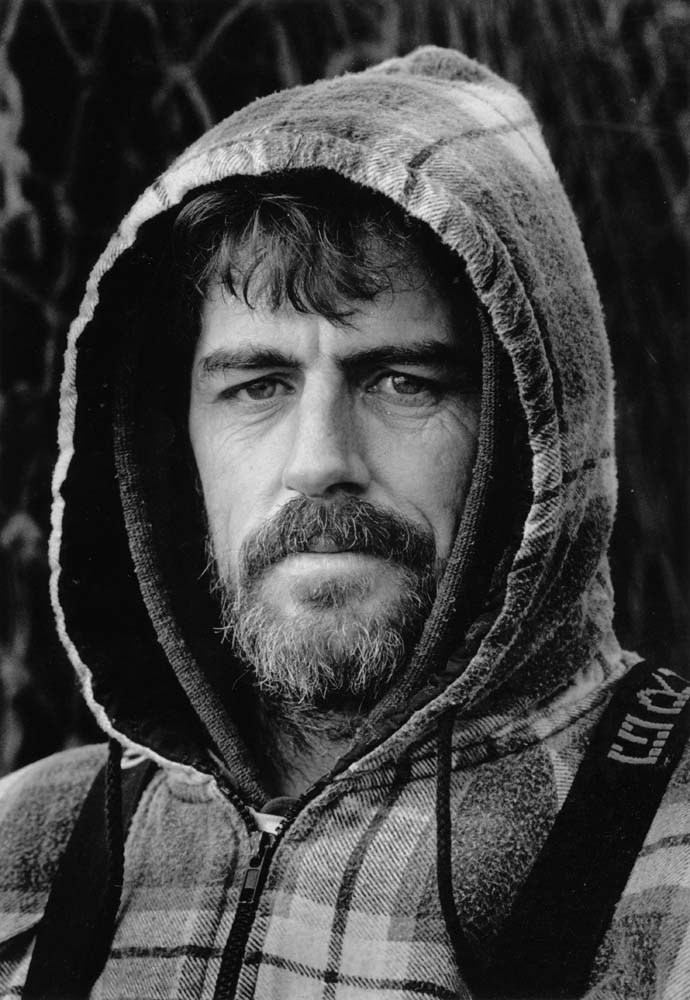

John “Woody” Woodbury, 38, shovels the deck of the Edward L. Moore at her berth on the Fish Pier in Portland, ME. Woodbury is an experienced deck hand having worked on commercial fishing boats since 1987.

Earlier in the year, a tragedy occurred when a similar problem on another vessel had been repaired improperly. Diminished structural integrity around the rudder post had been the likely cause of the sinking of the Two Friends in heavy weather. The loss of the two Portland fishermen on board, Harry Ross, Sr., and Larry Rich, had shaken the community. Last November, Captain Russell and Barbara Stevenson, the owner of Otonka Inc., and the ELM, promptly arranged to have their leaking boat pulled out in Gloucester, MA. Some $20,000 in repair and safety upgrades were needed before the boat was put back in service a month and a half later.

On this stormy December afternoon, Captain Russell and the crew are rewiring the electronics in the pilot house of the ELM. At the same time Dwayne Smith, the captain of the 35’ mussel dragger, Little Raspy, desperately calls his uncle, Ralph Smith, from Chandler Bay near Jonesport, ME (about 80 miles to the northeast of Portland). The captain of the Little Raspy relays the message that several large waves have swamped his boat. Ralph Smith immediately alerts the U.S. Coast Guard station in Jonesport. Fighting 12 to 14 foot seas, the rescue craft is on the scene in twenty minutes. The dragger is found with the bow out of the icy water and the stern submerged. Life jackets and a life raft float near the wreck. The crew — Captain Dwayne Smith, 21, Dawson Allen, 22, and Michael Laytart, 39, is missing. Around 8:30 this evening, Allen’s body is found washed up against the rocky shore of Popplestone Beach in Jonesport.

Woodbury loads more than $500 in groceries over deep snowdrifts to provision the boat for the crew of four on the 87’ commercial stern trawler as preparations are made for a ten day trip.

Friday, December 15 — The day dawns with cold, sunny skies. John “Woody” Woodbury, a deck hand on the ELM begins shoveling the heavy layer of snow off the deck. By mid-morning his girl friend, Michelle Lee, a pediatric nurse, arrives at the dock, and they head to the local Shop & Save supermarket to provision the boat for ten days of trawling. Woodbury pays $500 for four carts of groceries. Back at the pier, they reach over high snow banks to load the groceries. Meanwhile, in Chandler Bay, the search for the bodies of the two missing fishermen continues. Hundreds of local residents comb the coast. Fishermen drag the bottom of the bay. Helicopters search overhead. The day ends with diminishing hope; only one fisherman’s boot turns up.

At low tide, Captain “Scotty” Russell bids his girlfriend, Sue Conner, a cheerful goodbye as he is about to leave for his first fishing trip in six weeks. The need for major repairs has kept his boat idle.

Saturday, December 16 — The provisioning of the ELM continues on this gray but calm morning. Fifteen tons of ice, 5,138 gallons of diesel fuel and thousands of gallons of fresh water fill the boat’s tanks. Maintenance chores continue inside the pilot house all day. Meanwhile the recovery effort for the remains of Dwayne Smith and Michael Laytart continue in the now calm waters where the Little Raspy foundered. Later this afternoon, divers locate Laytart’s body in the murky waters where their boat sank. Underwater visibility is only six inches, but persistence finally pays off with the discovery of Dwayne Smith’s body a little while later. Smith, unmarried, has been dating a local woman over the last year. Dawson Allen leaves his wife, Dawn, and daughter, Taylor, two-and-a-half-years-old. Michael Laytart leaves his wife, Pamela, and two children: Charity Joy, 3, and Anthony, 6.

On December 18, at 3:15 p.m. the crew departs Portland, ME, for fishing grounds 120 miles to the east in an area called “Wrecked Bottom” and “The Hat.”

Sunday, December 17 — Heavy rain and gale force winds delay the ELM’s departure as the captain, first mate and two deck hands gather at 9 a.m. to complete refitting and maintenance tasks. There is a report that a cruise ship sunk off of Cape Henry, VA in 30’ seas. Fortunately, no passengers are on board and the entire crew of 35 are lifted safely off by the Coast Guard.

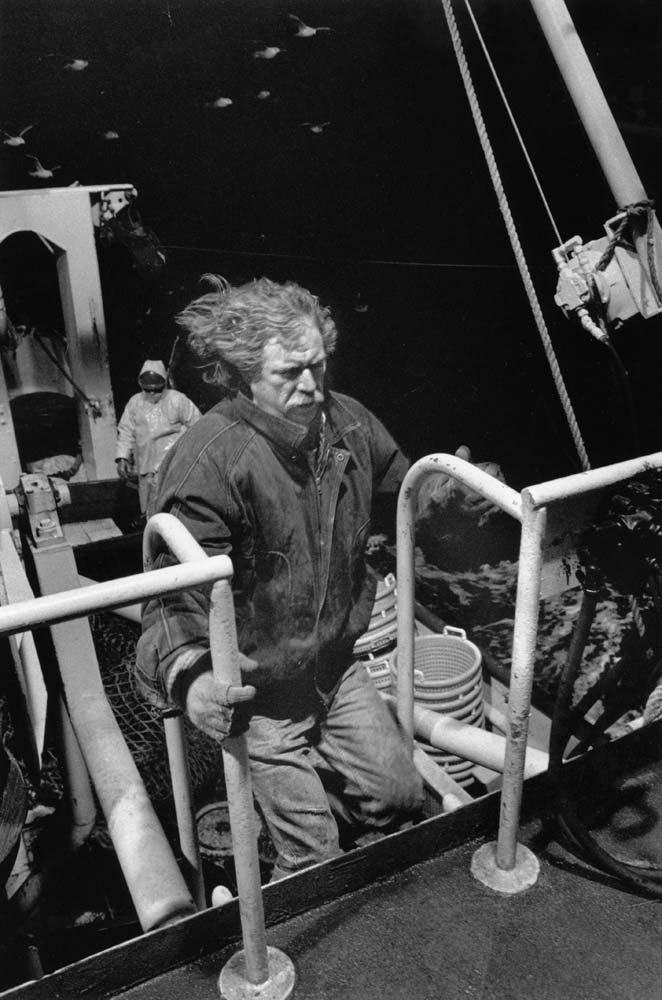

The Edward L. Moore eases away from the pier. Larry Thompson, 55, an experienced commercial sword fishing boat captain is a temporary deck hand for this winter off-shore trip.

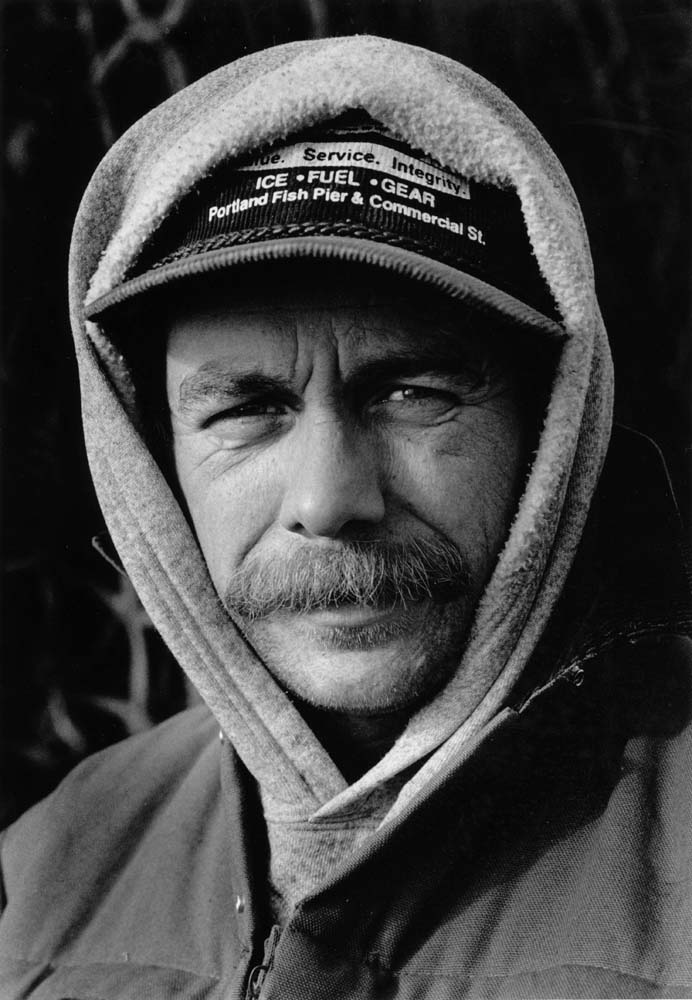

Monday, December 18 — Under bright skies, in gusty winds, crew members say goodby to friends and loved ones in the early afternoon. Captain Russell gathers First Mate Gabriel “Gabe” Fula, 40, and deck hands Larry Thompson, 55, and John Woodbury, 38, to the roof of the pilot house for a safety walk-around. They review life raft deployment procedures and the location of survival suits, life rings and fire extinguishers. Hatch cover opening and closing is demonstrated. Russell stresses orderly work areas, starting with his own. “If the pilot house is a mess, below deck will be a mess, and you know the rest of the boat will be that way too.” The ELM is known as “The Rehab Boat” because of Captain Russell’s zero tolerance policy for drugs and alcohol on board. He speaks with the calm authority of experience. There is little opportunity to misinterpret his orders. As he puts it,”If I have reason to suspect drug or alcohol use on board, I’ll go through their things and drop whatever I find over the side in front of them.”

First mate Gabriel Fula, repairs a jammed pulley block at the end of the outrigger. Heavy steel “birds” have been lowered from the starboard and port side outriggers to increase the stability of the boat on the open ocean.

After the net is released, heavy steel “doors,” weighing a ton each, are deployed. They open the mouth of the net and keep it to the bottom as the boat trawls forward at about 3 knots. Woodbury says, “When it’s flat-assed calm like this, we’ll sure pay for it later.”

At 3:15 p.m., Woodbury casts off the bow line. Thompson catches the mooring line at the stern and Woodbury jumps aboard the ELM as it eases away from the pier. Thirty minutes later, while still in the shelter of the harbor, First Mate Fula deploys the heavy steel birds by releasing winches that lower the outriggers on the port and starboard sides. The port side bird dips beneath the water’s surface and begins to provide stability to the boat as it heaves in the choppy inlet just past Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse.

The groundfish catch of haddock, pollock, cod, monkfish, hake and flounder is released from the net after a four to five hour trawl. First Mate “Gabe” Fula, left, controls the winding of the net as deck hands release the catch.

Fula quickly notices that the cable in the starboard outrigger block is jammed. The steel bird cannot be deployed fully. Without hesitation, he nimbly climbs to the end of the steel outrigger. The gusty “down east” wind buffets him as he uses hand tools to free the cable in the block. The rolling of the boat sends him high above the skyline and then dips him nearly to the waves below. He rides this sea driven roller coaster until the crucial repair is completed. Fula immigrated from Portugal when he was fourteen. “I started fishing when I was nine, back in the old country.” While he has fished in New England for over 23 years, he has been working out of Portland for only three-and-a-half years. “I have fished out of New Bedford (MA), Boston and Half Moon Bay in California . I have always gone for the bigger boats. They are pretty well safe. Usually if I don’t like a boat, I get away from it. I try to stay away from s– that might happen.”

Captain Russell, who stands 6’3″ tall, steps up the throttle on the ELM to seven or eight knots at 4 p.m. as the boat “turns the corner” into unprotected ocean waters. Deck hand Thompson notes with satisfaction that “the wind is on our butt” as everyone settles in for the 12 hour steam. The ELM‘s course is set for the fishing grounds called “Wrecked Bottom and The Hat,” 120 miles due east.

Tuesday, December 19 — The 671 horsepower Caterpillar diesel engine goes quiet. This silence is quickly replaced by a loud drone emitted from the pair of main winches as they begin to unwind net cable at 4:30 a.m. Russell has set the ELM’s throttle down to three knots for trawling. Fula, Woodbury and Thompson cast eerie shadows as they work at the stern to set the fishing gear. The gloomy orange glow of sodium vapor work lights etch the laboring fishermen against the black winter morning. The net is released by the first mate and deck hands to the bottom, a depth of 90-100 fathoms; the net’s mouth is kept open wide on the ocean floor by giant steel “doors” each weighing a ton.

By 8:15 a.m., the net is hauled back for a short tow to test its effectiveness. Only five or six-hundred pounds of cod, haddock, flounder and monkfish spill from it. With the ocean almost still and the temperature in the 40’s, Woodbury remarks, “When it’s flat-assed calm like this, you know you are going to pay for it later.” The fishing improves. On the third haul-back, 14 baskets of cod, haddock, pollock and hake are brought aboard. The catch must be gutted, sorted and loaded into large laundry type baskets. These are lowered into the fish hold where the fish are stacked neatly into layers, then iced. When the gutting and packing are complete, scarcely one-and-a-half hours remain for rest and meals before the cycle repeats itself.

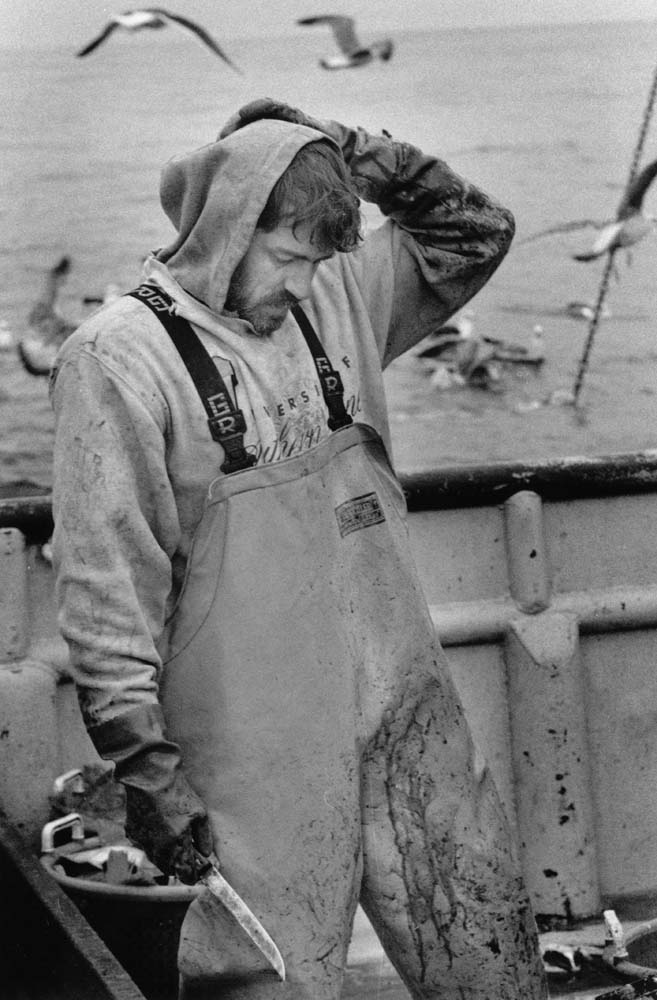

Woodbury, with his gutting knife in hand, takes a break from dressing the catch. Once the net is set out again the two deck hands and the first mate must gut the entire catch before loading it into the fish hold.

Wednesday, December 20 —The steel-hulled ELM is 90 miles due east of Portsmouth, NH, as it plows through six to eight foot waves that arrived with first light. By 5:30 p.m., the boat is rocking and rolling heavily as sharp, icy, wet gusts buffet the sturdy hull. At 11:30 p.m., the net rips open on the bottom, tearing out a large section, releasing most of the catch. In this fierce wind, captain and crew patiently sew the net before setting it out again. Russell explains that the waters were named “Wrecked Bottom” because the area is an historical fishing ground where the ocean floor is littered with wrecks. Captain Russell says, “Many of the wrecks have been charted so they can be avoided, but occasionally the net will hang up on an obstruction requiring a quick response from the helm to avoid major damage.”

Thursday, December 21 — Along with a 20 mile jog to the south, east of Boston, the repairs to the net last night pay dividends during the 2:30 a.m. haul-back. Their best catch yields over 20 baskets of fish. With a basket weighing between 50 and a 100 pounds, over 1,500 pounds of fish are added to the iced catch below. His gutting knife in hand, Woodbury brags about a recent dream catch when they brought 15,000 pounds on board in a single haul-back. Under gloomy skies and calm seas, each subsequent tow yields a solid haul. Thompson observes, “With four tows per day we need to catch at least 3 to 4,000 pounds per day to do good.”

Friday, December 22 — Twenty-three baskets are hauled back on the 12th return of the net, during the early morning hours. But exhaustion is beginning to set in, with the crew’s unrelenting round-the-clock schedule. Adding to their worn out condition is the rotating watch, which requires each crew man to do night relief duty for the captain in addition to his regular haul-back cycle.

As the weather begins to deteriorate, Thompson puts Ace bandages on his wrists and says, “Starting to put the armament on now.” Around 8:45 a.m., Woodbury notices the barometer falling sharply and comments, “If the barometer gets down to 29 you better not be around here.” His prediction that bad weather would follow the good comes to pass by 7:30 this evening, with a storm coming on strong. Despite the storm, Fula grills large boneless rib eye steaks in the galley in celebration of the consistently good fishing. An average of 6,000 pounds of fish caught per day now are packed in the fish hold. Tomorrow the crew will vote whether to come home early for Christmas Eve or stay for the full ten day trip. It’s clear that if the fishing remains this good, they’ll all agree to stay. With a larger boat, winter fishing has its advantages, despite the danger and harsh weather. Says the captain, “The prices are higher. The smaller boats can’t go out, so there’s less competition.” Indeed, it seems as though the ELM is sharing the entire fishing grounds with only an occasional freighter passing in the distance.

The Edward L. Moore moves on to a new fishing location because of the rising sea. This is no deterrent to the stoop labor required to prepare the catch or to the aggressive seagulls squawking loudly for a meal.

The wind has gained strength since morning. The sea is green and churning. Each dip into the trough of the wave sends icy spray cascading over the bow and rails. By the evening haul-back, gale force conditions prevail. They test the mettle of the crew in this hostile open ocean environment. At 10 p.m., when the entire catch had been dressed, a roaring 15’ to 18’ foot wave rises out of the stormy, black night, slamming over the starboard side. Woodbury’s first reaction is to throw his sharp gutting knife into a corner, “No sense having that in your hand when you are tumbling around in the water.” Fula shouts in fear as the wave hits, “I’m going,” believing that the wave might take him over the side. He takes the full force of the wave, as it somersaults him four or five times to the stern. Remarkably, he manages to stay in the boat. Thompson surfs on the wave, over the fish hold hatch to port, managing to grab hold of the spare trawl netting to save himself. Later, Thompson talks about his close call: “If you go overboard in this weather you’re f———- gone.” He pauses, and then continues, “At my age a heart attack would probably finish me off first.” In 34 degree water, it is estimated that if a rescue is not accomplished in six minutes, immobilizing hypothermia will set in. Fula adds, “I’ve been hit by these waves before, I know what they sound like. I crouched down so it wouldn’t hit me so hard.”

The wave completely swamps the working deck area. The soaked, freezing fishermen dive into the swirling tide in an effort to reach the boat’s scuppers. These are capped openings in the sides of the boat which must be opened quickly to release water before another wave hits and causes the boat to founder. Eighty percent of the dressed catch that has not been stowed below yet, sloshes through the scuppers and back into the sea, another blow to the fishermen. The captain quickly sets a course for a new fishing location, with the crew releasing the net again an hour later.

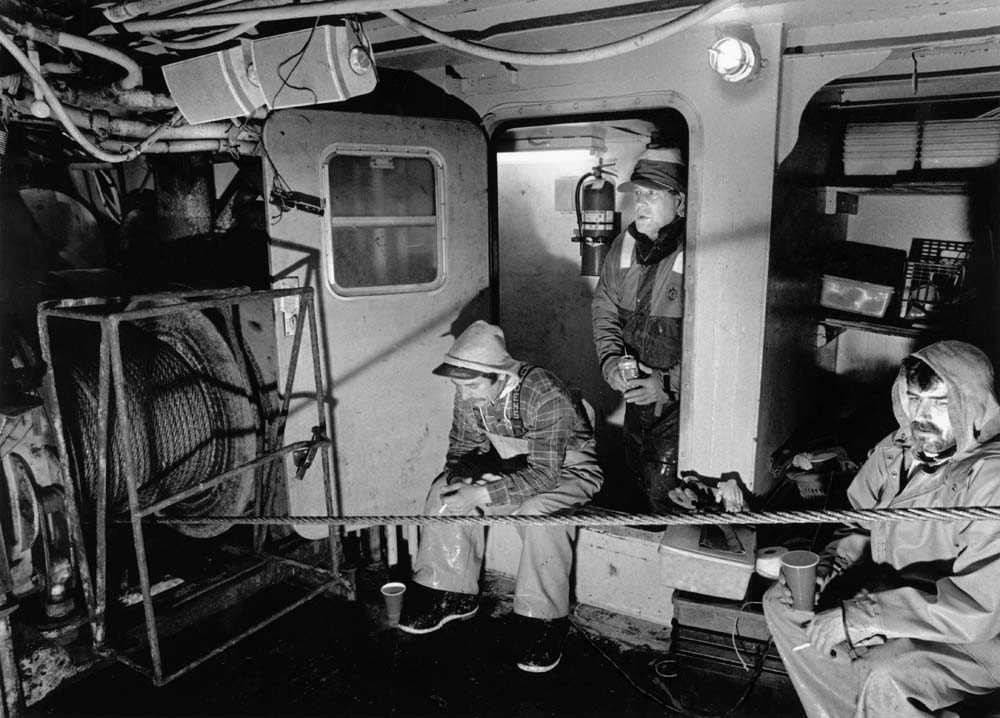

The crew seems stoic. Danger is accepted without complaint, though the crew’s response to the battering from the wave, is anything but casual. The men retreat to the galley to change into dry gear and drink coffee. Fula, who took the worst hit, is uncharacteristically quiet and goes back on deck to light a cigarette. The trio takes a 15 minute break outside the galley door before dressing the few fish that were not washed out to sea.

Crushed ice is loosened with a mattock so a layer can be shoveled on top of the fresh catch.

Saturday, December 23 — Two days earlier, before the mishap with the wave, Captain Russell had made an agreement with the crew: “If it’s bad, we’ll come home for the holiday.” Now, both weather and fishing are bad. With eight to ten foot seas, the net does not hold to the ocean bottom well enough to be highly effective. On the last haul back, less than four baskets of fish spilled out of the net — certainly not enough gain for the risk involved, particularly when these men could be home with family and friends for the holiday. By now the vote to head for port is a foregone conclusion. With the pressure off, crew members look foward to a full night’s sleep. Portland is not too far over the horizon.

Sunday, December 24 — Almost magically, the heavy seas wane, the clouds disperse and the sun brightens to a deceptively cold, clear day. In a flurry of activity, decks are washed down, gear is stowed, the engine room is inspected, and the catch is inventoried as the ELM draws nearer to the Maine coast. Showered and wearing street clothes, Woodbury tests his cell phone just outside the three mile limit. His first words are to his girlfriend, Michelle, happily alerting her to include him in Christmas plans. Next Gabe calls home. Darkness falls as the boat slowly comes through the harbor. It seems like an eternity before the trawler is securely tied to its berth. It takes only minutes for Russell, Fula, Woodbury and Thompson to pull themselves up to the snow-covered pier and take off into the crisp night before Christmas.

Fula, 40, ices down the catch. Fifteen tons of ice were brought on board for the trip. He began his commercial fishing career at age fourteen in Portugal.

Tuesday, December 26 — With little market for fresh fish on Christmas, the ELM sat idle at its berth yesterday. By 4:30 a.m. today, lumpers are unloading the 21,363 pound catch from the fish hold of the ELM. Lumpers are crews that specialize in unloading the larger boats in the Portland commercial fishing fleet. The catch is sorted by weight and species and prepared for auction by 10 a.m. Fish buyers roam the refrigerated warehouse of the Portland Fish Exchange, pulling the iced catch from large, plastic tubs to inspect it and occasionally sniff it for freshness, before the auction begins.

The crew endures wave drenching working conditions while dressing the catch. Later that same evening a 15’ to 18’ wave made such a roar that First Mate “Gabe” Fula shouted out to the rest of the crew, “I’m going,” meaning that he thought he was going overboard. Crouching down to reduce the force, Fula was somersaulted four times toward the port side at the stern, but managed to stay in the boat. Woodbury threw his sharp gutting knife into a corner to avoid being tossed into the water with the lethal tool in his hand. Thompson (not pictured) surfed with the wave, managing to grab hold of netting in his path as he was washed to the port side of the boat.

Scott Russell stands his 6’3” frame against the gale force wind. He has been the captain on the ELM for 19 years. The crew calls his craft, “The Rehab Boat,” because of his strict prohibition of drugs or alcohol on board. “If I have reason to suspect a crew member, I’ll go through their gear and dump whatever I find over the side in front of them.”

Before dressing the catch, while the net is being set out again, the crew takes a break by the galley door. The winch winds out the cable in front of them.

The ELM’s catch consists of 10,600 pounds of haddock, 2,700 pounds of pollock, 2,300 pounds of cod, 1,900 pounds of hake, 1,500 pounds of flounder, 500 pounds of gray sole and a few minor species. The return from the catch at auction totals $46,500. After fuel, oil, and ice costs are deducted, the crew divides 40% of that figure; Otonka Inc., receives 60%. The crew members also are paid a quarterly bonus equal to an additional 10% of their pay if they make at least a three month commitment to work on the ELM. The captain and first mate also receive bonus pay. For this trip the captain receives $6,000, the first mate $4,900, and deck hands $3,700 each. Otonka Inc., spends between $50,000 and $100,000 per year to maintain the ELM. The captain’s annual income ranges between $85,000 and $100,000; deck hands make between $50,000 and $60,000.

Lumpers unload the larger fishing vessels in the Portland, ME fleet. Working in a snow storm at 4:30 a.m. this lumper lifts out barrels of fish from the boat’s fish hold with a hoist.

Maggie Terry, North Coast Seafoods’ buyer, sniff tests pollock shortly before the auction at the Portland Fish Exchange.

After taking Christmas Day off, the crew returns to the pier by 8 p.m. and departs for their next fishing trip shortly before midnight.

Last December, from her office overlooking the commercial fleet on the fish pier, Judith H. Harris, Fisheries Program Manager for the City of Portland, listed from memory the name of each Maine fisherman who died in the year 2000. Nine commercial fishermen were lost, five were fishing out of Portland. According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, commercial fishermen face a fatality risk 28 times greater than all other occupations in the U.S. making this industry our nation’s most hazardous.

©2001 Earl Dotter

Earl Dotter is a freelance photographer from Silver Spring, MD, who is spending his Patterson year examining commercial fishing. This article was prepared with the assistance of Ann S. Backus, MS, Director of Outreach, Occupational and Environmental Health Program, Harvard School of Public Health and Judith H. Harris, Fisheries Program Manager, Portland, ME.