Douglas Goodale, by the age of 32, had 8 years of commercial fishing experience behind him when his job literally took his right arm and very nearly his life. Goodale was working by himself on his twenty-two foot purple lobster boat, “Barney,” about one mile off the coast of southern Maine near Wells Harbor. The rope hauling up his third set of double traps went slack in the heavy six foot seas and snagged on his antiquated winch.

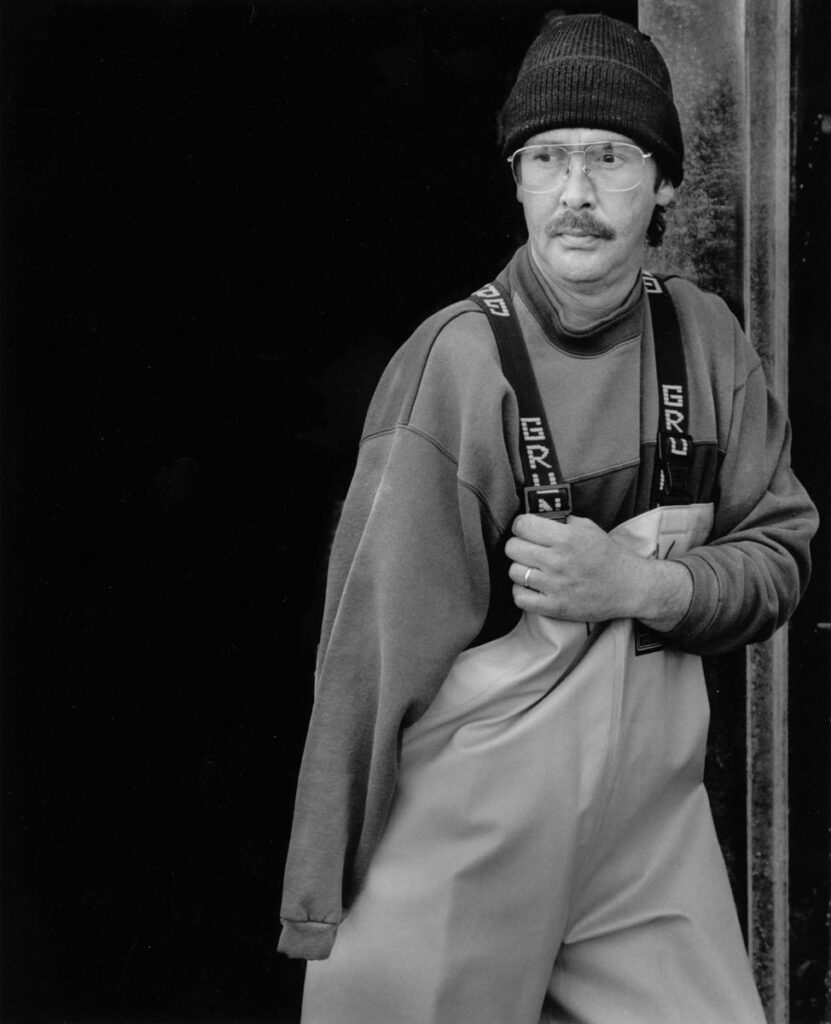

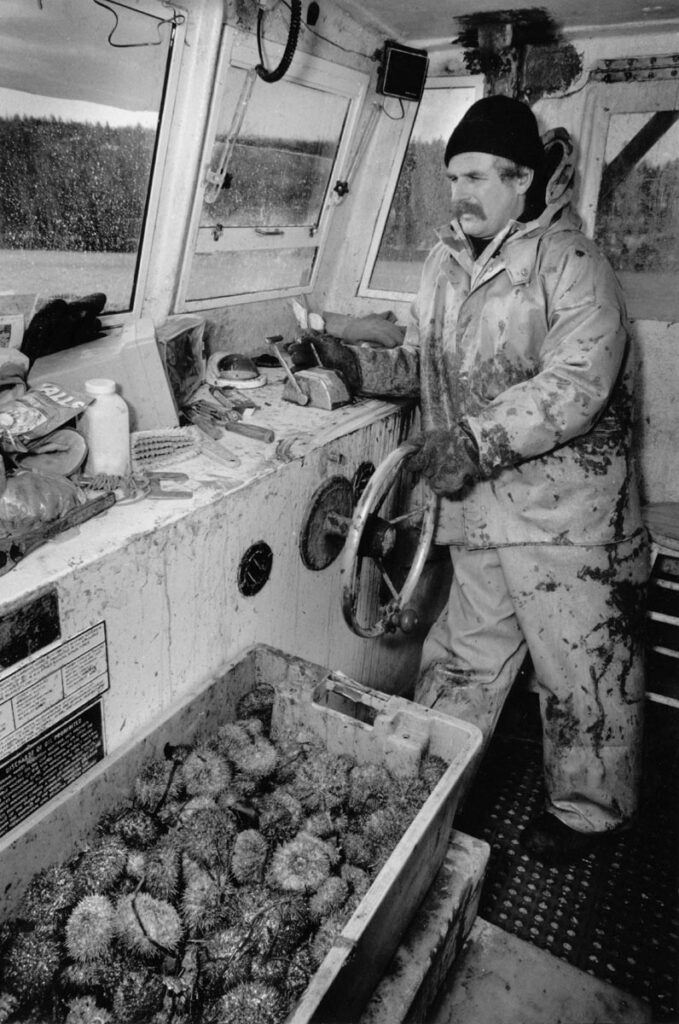

Douglas Goodale, 35, lost his right arm while lobstering off the coast of Maine in 1997 in a winch accident. He continues to fish commercially out of Wells Harbor.

While reaching for the winch cut-off switch, Goodale’s loose fitting right oil slicker sleeve got caught in the winding rope, pulling it into the winch head. In a moment of agonizing terror, his hand and then his arm were drawn in and crushed in the winding winch flipping him over completely and then out of his boat. With his arm still entangled in the turning winch and his body hanging outside the boat, the near freezing cold north Atlantic Ocean water jolted his senses. The fisherman’s survival instinct left him no choice but to try to get back in the boat. With adrenalin pumping through his body, Goodale pulled himself with his heavy waterlogged clothing up over the side using his left arm. Because of the way his right arm was twisted he had to dislocate his injured shoulder joint in the process. Staggering in the heaving boat, he broke the kill switch trying to shut down the winch. “Then I reached for my twine knife by the wheel, cutting through my oil skin to free my arm. I was bleeding quite a bit, but the cold ocean water and the twisting had cinched up the wound.” At full throttle, Douglas Goodale piloted his boat through the crashing waves to Wells Harbor. Yelling for help as he approached the wharf, his cry was heard by two fishermen who were preparing herring for lobster trap bait. Goodale, still standing was now ankle-deep in blood-tinged sea water. Twenty minutes later, with help from the fishermen, he was able to get off his boat and lie down on the ambulance stretcher. In comparison to Robert Rainville, a lobster man a few miles down the coast, Douglas Goodale could consider himself lucky.

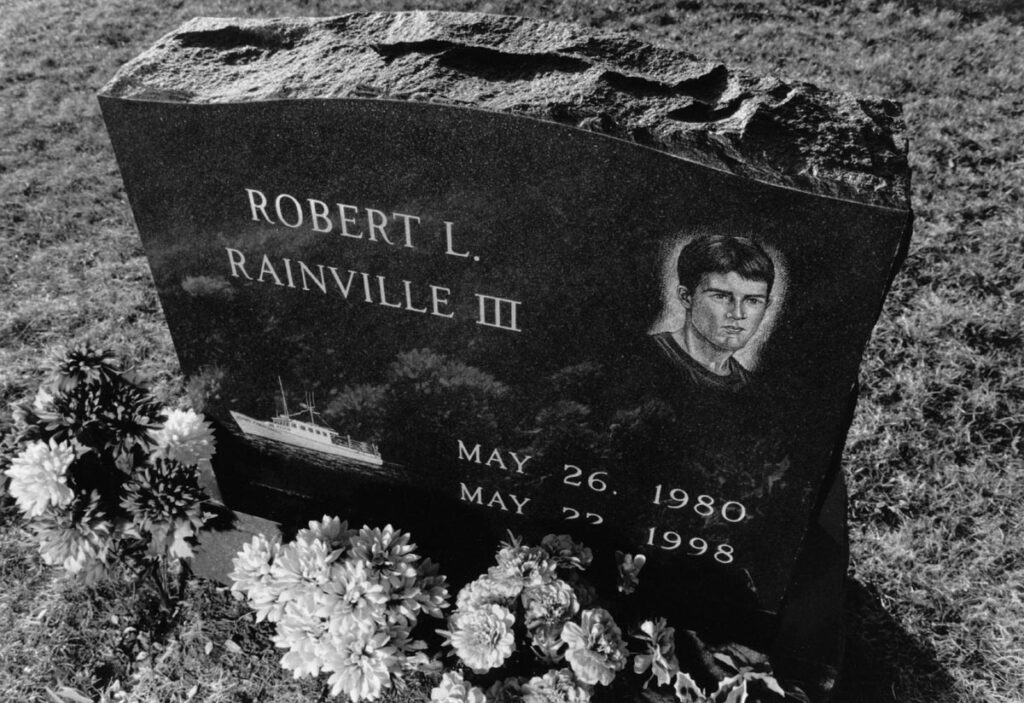

On May 22, 1998, four days before Robert Rainville’s eighteenth birthday, his lobster trap rope became entangled in the propeller of his forty horsepower outboard motor. With the prop out of the water, Rainville was reaching far over the stern of his disabled boat to disentangle the line. The stern of the boat was heavy with the upended motor and the weight of the fisherman. All it took was one good wave to swamp the boat. Robert Rainville’s body was found lodged in an underground reef on the day he would have turned eighteen. State police divers had traced the fisherman’s path by following his lobster trap buoys set in open ocean waters out of York Harbor, Maine. Unfortunately, trap rope entanglement in the propellers of outboard-motor-powered lobster boats continues to be a fairly common occurrence.

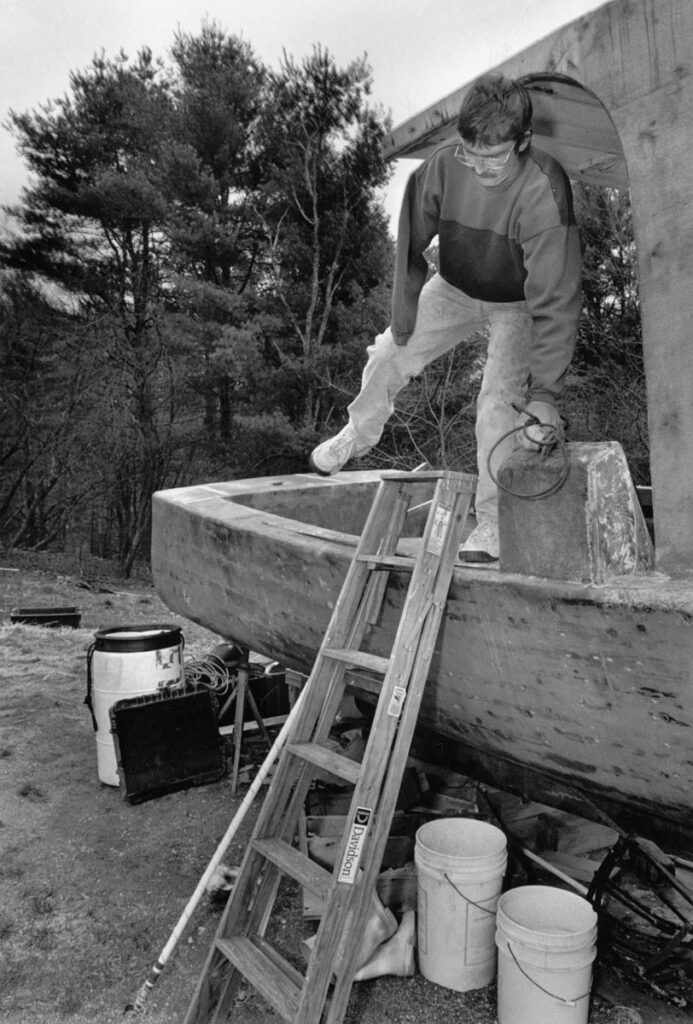

Robert Rainville, Sr., examines the recovered 14 foot skiff in which his son lost his life lobstering. Four days before Robert Rainville’s eighteenth birthday, his lobster trap haul rope became entangled in the propeller of his forty horsepower outboard motor. With the prop out of the water, Rainville was reaching far over the stern of his disabled boat to disentangle the line. The stern was heavy with the upended motor and the weight of the fisherman. All it took was one good wave to swamp the small boat.

“Down East” In February

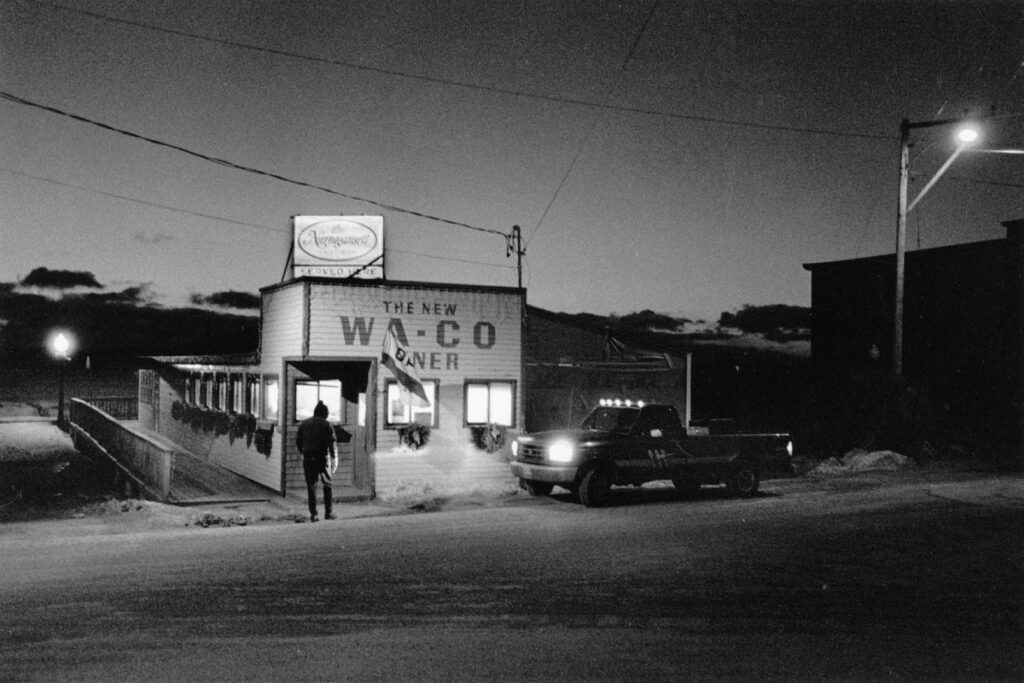

Eastport, Maine, located in Washington County, is situated farther east than any county in the United States. Washington County with 700 miles of miles of coastline incorporating bays, harbors and inlets, shares its northern border with Canada. Settled in 1789, Eastport has a current population of about 2,000. The town once boasted of 14 sardine canneries. Today there are none. In this “down east” part of Northern Maine the tides average 18 feet from high to low, a rate of over an inch a minute. Ships from around the world enter Eastport’s deepwater harbor in Cobscook Bay to load long logs and brown kraft paper for making boxes and grocery bags. Salmon pens share the shoreline of the bay with fishermen dragging the bottom for sea urchins and scallops in the winter season. A good number of the fishermen convert their boats to lobstering in late summer. While the sardine canneries are long gone, the advent of aquaculture has spawned vast stretches of salmon pens that pump a steady supply of live farm-raised salmon into the local processing plant. Bruce McGinnis owns and operates a thirty-two foot fiberglass-hulled scallop and sea urchin dragger called the Sea Wife. Dottie Tucker, his helper, he calls his “sternperson.” Dottie is a single mother with three kids at home. Bruce, like other fishermen in the area, makes time for second jobs. Between working as a longshoreman, when there’s a ship to be loaded and dragging the bottom of Cobscook Bay for sea urchins and scallops, Bruce is a busy man. Most Eastport fishermen begin their day at about 4:30 am with coffee at the WA-CO Diner, a downtown haven to fishermen since 1924. Snow is flying in mid-February as Bruce warms up the Sea Wife’s 220 horsepower diesel engine in the darkness and Dottie makes ready to cast off. Ice is caked at the vessel’s waterline. A snow squall stings her face as Dottie prepares the fishing gear. They head into 20 knot gusts with a wind chill of minus nine. Outside the breakwater that shelters Eastport’s commercial fishing fleet, it’s blowing too much to set the drag in the open waters of Cobscook Bay. In the protection of the boat’s heated cabin, the crew steams toward a series of sheltered coves until daybreak. No whistling is allowed on board as the dawn breaks. The fishermen say, “If you whistle the wind will blow.”

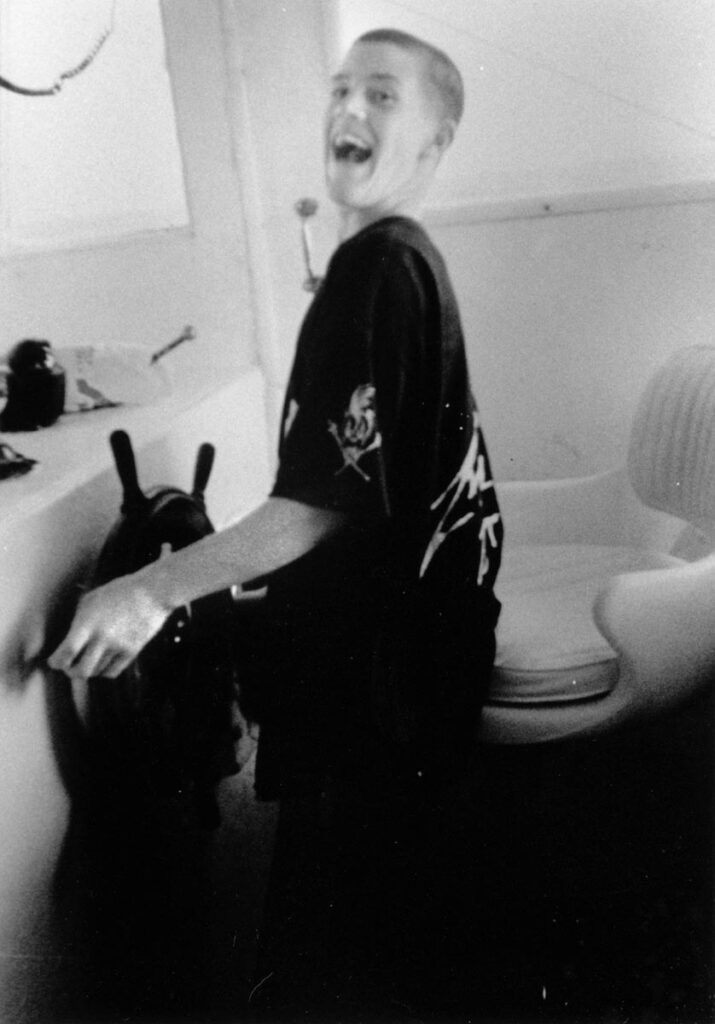

In happier times, at age fourteen, Robert Rainville III pilots his father’s 42 foot commercial fishing boat, “The Flying Frenchman.”

On reaching a sheltered cove, Bruce dons layers of insulated gear topped with a hooded rain slicker, rubber boots and gloves and releases the massive chain-linked drag into the sea. As the winch pays cable out through a pulley from a steel A-frame structure overhead, the drag sets to the bottom slowing the the boat noticeably. After they pass through the cove, Bruce sets the winch to pull the drag to the stern with its catch of seaweed, mud, starfish, rock and urchins. He positions the drag over a table constructed on the stern and releases the catch that then crashes to the table. As he drops the drag into the water, Dottie, and for a short time Bruce, sort through the muck, collecting urchins while casting off debris. Dottie measures urchins of questionable size, and gathers those that pass the test into a plastic laundry bucket, washes them over the side, and stows them in an urchin tote in the heated cabin. Urchin and scallop dragging operations are dangerous. Cables or the headgear can fail, sending heavy pulleys, and wire cable whipping through the air with a violent release of energy above the sternperson working at the table. Dragging boats can capsize and sink when the drag gets caught on the bottom. The high center of gravity characteristic of some scallop rigs increases the risk of capsize. Entanglement of hands and clothing in unguarded winches is a real possibility when fishermen work in icy, wet, slippery conditions on a rocking work platform. Life- threatening events take place with little warning, often dumping the crew into the frigid water before they have had time to put on survival suits.

Robert Rainville’s body was found lodged in an underwater reef on the day he would have turned eighteen. State police divers had traced the fisherman’s path by following his lobster trap buoys set in open ocean waters out of York Harbor, Maine. Today, commercial fishermen face a fatality risk 28 times greater when compared to all other occupations in the United States, making this industry our nation’s most hazardous.

Lobsterhaven

Vinalhaven Island sits in Penobscot Bay off the coast of Rockland, Maine. Travel between the mainland and the island is an hour-and-a-half ride by ferry. The 10 by 5 mile island was settled by English colonists in 1760 after the French and Indian War. By 1826, the quality of Vinalhaven’s granite had been discovered and for the next 100 years, Vinalhaven was one of Maine’s most active granite quarrying centers. The Islanders are proud that the Brooklyn Bridge and many famous 19th century Beaux Arts buildings in the United States were constructed of Vinalhaven granite. With the closing of the quarries and the decline of large fin fish stocks, the island has become home to one of the largest lobstering fleets in the world. Island life is tuned to the lobster’s life cycle, giving a palpable rhythm to the daily tasks of both the fishermen and their families. Norah Warren trapped lobsters before she became the manager of the Vinalhaven Fishermen’s Co-op in 1997. Her tasks vary from making sure there is enough herring on hand to sell to the lobstermen for bait to keeping track of each fishermen’s catch. Early this April, she was loading the plastic totes filled with live lobsters on a conveyor belt when she looked up to see fishermen from the co-op desperately trying to get a rope tied on a lobster boat that had capsized and was sinking in the harbor. The previous night’s rain had left this boat low in the water at its mooring. A sudden shift in the wind had brought more water over the side, creating the emergency almost out of nowhere. As in this case, a fisherman’s ordinary routine can suddenly, and quite literally, turn upside down. A lobsterman uses lots of rope. This year a fisherman is allowed 800 traps, each with a rope and a color-coded floating buoy on which his lobster permit is plainly marked. Just a few years ago, 1600 traps were permitted. A lobsterman, most often working alone, will find his first buoy bobbing in the water off shore by consulting his fish finder for its precise location . Steering his boat with one hand and holding on to a gaff in the other hand, he will lean over the side and hook the rope attached to the buoy. The fisherman places the rope in the winch or pot hauler and pulls a single or perhaps several traps up from the bottom. Coils of rope drop to the deck next to the feet of the fisherman as he opens the trap to remove the lobsters. He measures each lobster to be sure it is of legal size and checks for females by looking for eggs or a notched tail. Female lobsters must be thrown back. He baits the traps and pushes them over the side while throttling forward.. Without knowing it, a bight or half-hitch of rope may have caught around his boot. When this happens, the lobsterman is jerked off his feet as the trap rope pays out and the hitch tightens around his boot. He is then pulled to the stern. If he has prepared for an entrapment like this, he will be able to reach a sharp knife, if not, he will be pulled into the frigid water with his sinking traps. This situation may rapidly become more serious if his unmanned boat circles back around and hits him.

Most fishermen in Eastport, Maine, begin their day at about 4:30 am with coffee at the WA-CO Diner, a down-town haven to fishermen since 1924.

Last Call – Gloucester

New England’s fishermen have a saying, “never take a suitcase onboard unless you want to meet your maker.” It’s not hard to imagine why they have such concerns in Gloucester, Massachusetts. According to Sebastian Younger in his 1997 book The Perfect Storm, “Each year during the 19th century, Gloucester, Massachusettes typically lost to the sea about 200 men employed in fishing – four percent of the town’s population.” In a brochure currently distributed by the Gloucester Tourism Commission the following grim history is outlined. In 1623, three years after the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, a group from that colony arrived looking for favorable fishing grounds. Immigrants from the Dorchester Company of England permanently settled the area and named it Gloucester after its namesake in England. Since its founding, 10,000 Gloucester fishermen have been lost. In 1862 alone, 15 of the 70 schooners fishing Georges Bank vanished in storms, creating 70 widows and 140 fatherless children. In 1879, 249 fishermen were lost, the worst year on record in Gloucester. Perhaps in response to this loss, a few years later the Church of Our Lady of Good Voyage was built on a hilltop to ensure seafarers a safe return home. High above the church, Mother Mary cradles a sailing schooner in her arms, to reassure returning fishermen.

In the protection of the breakwater, Eastport’s commercial fishing fleet lies idle. The boats are rigged for scallop and sea-urchin dragging in Cobscook Bay. In this “down east” part of Northern Maine, the tides average 18 feet from high to low, a rate of over an inch a minute.

It is from Gloucester that the Andrea Gail was lost with all hands in 1991. That tragedy is about to be given new life in the feature film adaptation of Sebastian Junger’s book to be released this June. If the film follows the book faithfully, movie goers will get a very personal and up-to-date feeling for the experience of the Gloucester fishermen who work far offshore in the North Atlantic in pursuit of swordfish, tuna and halibut. The six men who died on the Andrea Gail were not the only ones to pay a price. Since the founding of this fishing community, the wives, children, close family and friends who are left behind have often lived without knowing the fate of their missing loved ones. One only has to walk Gloucester’s Beechbrook Cemetery to feel the burden this community has shouldered. The white anchors set in the earth around the graves poignantly bear witness to the loss.

Close to a rocky cliff in Cobscook Bay, a scallop dragger hauls up the drag in preparation for unloading its contents on the table at the stern of the boat.

Dottie Tucker, the sternperson on The Sea Wife, sorts through the catch on the table. Cables or the headgear above the sternperson can fail, sending heavy pulleys and wire cable whipping through the air with a violent release of energy.

A Hopeful Sea Change

Douglas Goodale’s wife, Becky, “was kind of amazed he went right back to work.” During the winter following his accident on the “Barney,” Goodale worked for the Wells Highway Department as a painter and at the local transfer station sorting recyclables. Goodale’s frustrations revolve around tasks that require two hands. Surprisingly, having only one arm has not kept him from two seasons of lobstering or from completly overhauling his 35 foot wooden-hulled lobster boat. He has renamed the boat Tabbybrat, after his youngest daughter. Goodale wishes he could “take one of those long balloons to make it look like I still have both arms.” Severe tendinitis problems are showing up in his good arm. “I know I can’t keep doing hull work with it all day.” Of his return to the life of a fisherman he says, “I’ve changed the way I work now. When the lobsters move offshore in the winter, I move home. I call myself a fair-weather fisherman. If I have to hold on, I can’t work.”

In the heated cabin Bruce navigates through sheltered coves. No whistling is allowed on board as fishermen say, “If you whistle the wind will blow.”

The previous night’s rain had left this Vinalhaven Island lobster boat low in the water at its mooring. A sudden shift in the wind brought more water over the side, creating the emergency almost out of nowhere. As in this case, a fishermen’s ordinary routine can suddenly, and quite literally, turn upside down.

In Eastport, Maine, some of the scallop and sea urchin draggers are refitting the heavy steel headgear above the deck with aluminum replacements. The reduced weight keeps the boat’s center of gravity closer to the deck, lowering the risk of capsize. Bruce McGinnis has rigged a further refinement that lowers the main drag pulley from high above to a position less than half the headgear’s full height, also lowering the center of gravity considerably. Jeff Smith, who has worked out of Eastport as a sternman with Butch Harris on Harris’s drag boat The Miss Halie, has rigged a plastic barrel on the deck fed by warm water from the engine’s cooling system to wash the fishing harvest. This is safer than the practice of leaning over the side of the boat to wash urchins and scallops. The winch entanglement issue remains a major concern, little progress has been made toward a practical guard design or toward the acceptance by the fishermen of the need for installing guards on winches. On Vinalhaven Island, five working fishermen have been trained as Emergency Medical Technicians (EMT’s) through the efforts of Dr. Rick Donahue, director of the Islands Community Medical Services. The fishermen can respond out on the water to accidents or health emergencies. The program also provides every fisherman with a waterproof “Medical Emergency Card” that lists concise tips for treating hypothermia, chest pain, amputation and burns and gives directions for contacting EMT’s and island- based emergency assistance. Fishermen mindful of safety will select clothing that reduces the risk of entanglement, and they will remove, for example, drawstrings and decline using excessively loose fitting rain gear. Some fishermen who have been pulled off their boat when entangled in trap ropes have installed “gag lines” along the side and across the stern that can be pulled to shut down the boat’s motor in the event that they become entangled. Several lobster boat designers have begun to install rope lockers that capture the trap rope as it spools off the winch, effectively eliminating the possibility of the fisherman getting caught in the rope.

One has only to walk Gloucester’s Beechbrook Cemetery to feel the burden this community has shouldered. According to Sebastian Junger in his 1997 book, The Perfect Storm, “Each year during the 19th century, Gloucester, Massachusetts typically lost to the sea about 200 men employed in fishing–four percent of the town’s population.”

A lobsterman steers his boat with one hand and holding a gaff with the other hand, will lean over the side and hook the rope attached to the buoy. The fisherman places the rope in the winch or pot hauler and pulls a single or perhaps several traps up from the bottom. Coils of rope drop to the deck next to the feet of the fisherman as he opens the trap to remove the lobsters. Without knowing it, a bight or half hitch of rope may have caught his boot. When this happens, the lobsterman is jerked off his feet as the trap pays out and the hitch tightens around his boot. He is then pulled to the stern. If he has prepared for a moment like this, he will be able to reach for a sharp knife. If not, he will be pulled into the frigid water with his sinking traps.

Surprisingly, having only one arm has not kept Douglas Goodale from two seasons of lobstering or completely overhauling his 35 foot wooden lobster boat. Severe tendinitus problems are showing up in his good arm. “ I know I can’t keep doing hull work with it all day.” Of his return to the life of a fisherman he says, “I’ve changed the way I work now. When the lobsters move offshore in the winter, I move home. If I have to hold on, I can’t work.”

Dewey Sandborn is assisted by his wife, Stephanie, loading lobster traps on Vinalhaven Island as they prepare for the season this April. The lure of independence, of being one’s own boss, has a special attraction for fishermen, particularly in New England. Many fishermen who have had near-death experiences have come to believe that without changes in working condi-tions, the true price of fish is too high.

No Fisherman Is An Island Unto Himself

The lure of independence, of being one’s own boss has a special attraction for fishermen particularly in New England. Many fishermen who have had near-death experiences have come to believe that without changes in working conditions, the true price of fish is too high. The changes made by retrofitting their boats, and reducing the risk in their work practices suggest they are no longer willing to sacrifice their own well- being and lives or risk making the lives of those they love painful and difficult. What, after all, is the price of fish?

The changes that Bruce McGinnis and Dottie Tucker have made retrofitting The Sea Wife and in their work practices suggest they are no longer willing to sacrifice their own well-being and lives.

Since 1623, Gloucester fishermen have left this harbor in search of their livelihood in the north Altantic. The wives, children, close family and friends who are left behind have often lived without knowing the fate of their missing loved ones.

Maine fishermen Douglas and Becky Goodale spend a rare moment in quiet conversation. Becky reflects, “With the kids at home with the grandmothers, we work extra safely when we are both out here. They could be orphans if we’re not careful.”

©2001 Ann Backus and Earl Dotter

Ann Backus, MS, is Director of Outreach, Department of Environmental Health and Occupational Health Program, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA. Earl Dotter is a freelance photographer from Silver Spring, Maryland, who is spending his Patterson year examining commercial fishing.