MEMPHIS, Tenn.–There is a small black camera on the lawn of Graceland, where Elvis Aron Presley, King of Rock and Roll, once lived, then existed, and finally died. The camera points at Graceland’s green and white wrought iron gate. At one time it transmitted to the bedroom that belonged to Elvis Presley. In this way he could watch the fans who were compelled to stand at his gate, should he wish to. These were men and women who came to the gate in groups of two’s, and three’s, and four’s; men and women who think of themselves less as workers, mates, and parents than as Elvis fans. Their allegiance to that self-definition became a twenty-four hour vigil at the gate, for virtually all the days and all the nights of each of the twenty years that Elvis Presley lived cloistered within it.

Across the street from the Graceland gate, one hundred yards up the boulevard named for Elvis Presley, there is a small, all-night cafe called The Hickory Log. It is here that Elvis fans have always gathered, and in winter, when Elvis Presley was still alive and his second story bedroom window was not obscured by sycamore leaves, they would sit and gaze at the light in his room. It made them feel good to know he was close by.

On occasion they would notice that the lawn camera seemed to shift, imperceptibly at first, then sufficiently to suggest its electronic eye now was focused on the huge picture windows of The Hickory Log. At such moments, they believed, Elvis Presley was watching them, and they would picture him alone in his room, perhaps lying on his bed, viewing silent, televised images of those who worshipped and adored him, and who were, in physical distance at least, just one hundred yards away.

Or so they think. And so they say.

That is one of myriad tales recounted by fans of Elvis Presley, though such stories should not be taken as evidence that the storyteller agrees with what an impartial observer might deem to be the story’s point. For these men and women are endowed with the selective vision characteristic of only the most steadfast lovers, and even those irretrievably fixated on Elvis Presley for twenty years or more have retained the propensity of early love to discount all information that does not neatly corroborate their most hopeful, cherished preconceptions.

They are also dreamers of the American Dream, believers in those oft-told fables that make Horatio Alger the happiest American legend. It is The Dream that lies at the heart of their devotion to Elvis Presley, and The Dream is the abiding belief they shared with him, and he with them. “When I was a boy,” he said in 1971, “1 read the comic books and I was the hero in the comic book. I saw the movies and I was the hero in the movie. So all my dreams have come true a thousand times.” Six years later he lay dead and alone on the plush blue carpet of his bathroom floor, a corpse with heavy jeweled rings on its swollen fingers, Exhibit A in the case to prove that The Dream is not exactly viable.

But the inviability of The Dream is not a facet of stories told by the men and women who raise money for charity in Elvis’s name at progressive dinners that feature well-done beef and lime jello. The inviability of The Dream is not part of the story at all according to those whose most treasured possession is a rose that came right off Elvis’s coffin. Nor is it part of the story according to the woman who made a bronze bust of Elvis and presented it to his father, even though Vernon Presley was weak and in poor health and the bust weighed thirty-eight pounds. Nor would it likely be part of the story as told by the woman who added to the graffiti in the Hickory Log bathroom by writing with a ballpoint pen: “I always wanted to meet you. Now I’m here and you’re gone.”

Till The End Of Time

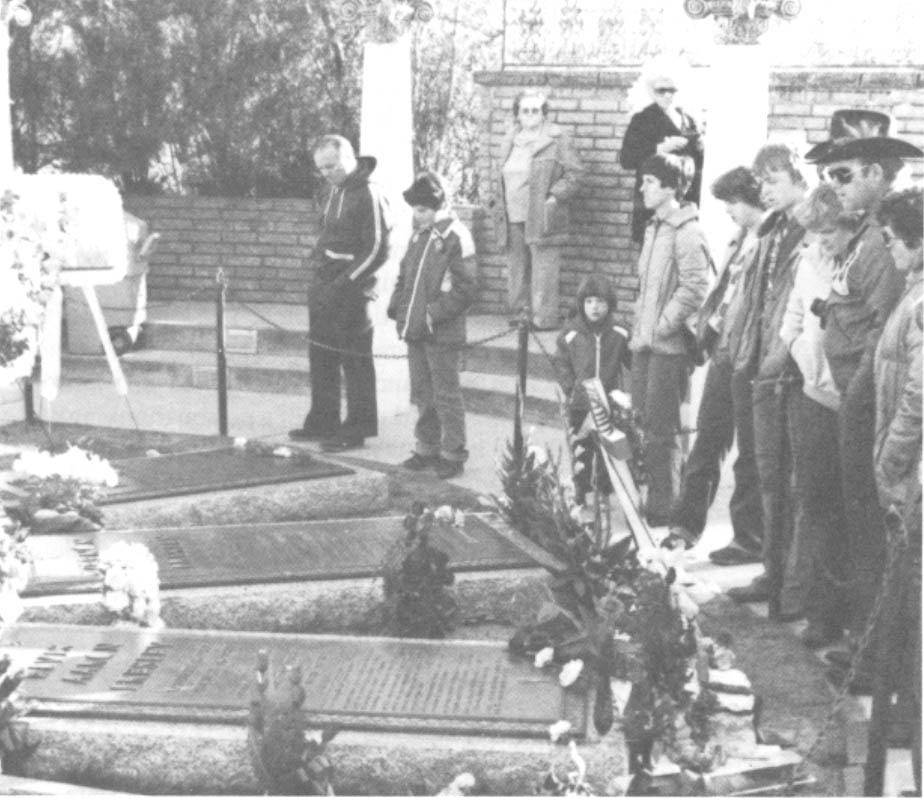

Elvis Presley fans conserve their money for two trips to Memphis each year. The money accumulates in special bank accounts and empty king-size peanut butter jars and is spent in August, on the anniversary of his death, and in January, on his birthday. On these occasions the solemn funereal parade up the hill to his house, and then beyond it, to his grave, is so relentless that the Graceland guards have ceased trying to measure it. In the course of ordinary winter weeks his grave is visited by 1800 men and women. On ordinary days of summer this number increases to 3000 visitors daily.

| Hundreds and often thousands of fans visit Elvis Presley’s grave each day. (Photo by Barry Grant) | |

|

|

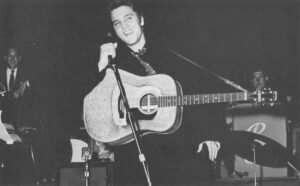

This is a phenomenon that has no precedent in American life. Elvis Presley once said he was “Just a singer”, but in fact he was the repository of an astonishing amount of adoration. When he was alive, his fans were known to sell cherished possessions to raise money for trips to cities where he played; they were also known to take second mortgages on their homes. When he died, the national response was so intense that Mike Royko of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote that in the fourteen years since the assassination of President Kennedy, years in which Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King were murdered, “Nothing has equaled the present national grief.” Since his death, in the first thirty-six months immediately following it, fifty-four books about him were published. Yet somehow all this has been either dismissed, or regarded as some lowerclass form of hero worship, or lately, as necrophilia, and questions these facts might evoke have been ignored. What does it mean when people give a public figure more attention and love than they give anyone in their immediate world? What needs are fulfilled by being a fan? What does it say about how divested people feel, about how much they want to connect with power, and at the same time give their power away? How did the Presley phenomenon begin and why has it persisted for twenty-seven years? What are its religious underpinnings? Since so many fans are women, can any valid comparisons be made to the women’s movement? What were his real achievements as opposed to his perceived ones? And what price did Elvis Presley pay for The Dream?

But now the man who had been so right when he said, as a boy, “I don’t sound like nobody,” lies beneath a marker made of marble and bronze. For reasons no one can explain, his name is misspelled on the headstone: ELVIS AARON PRESLEY it reads, with two A’s instead of one. In winter ice forms in the triangles of the A’s, and in the letters P, 0 and R. By noon the ice softens to water, like immovable tear drops, by four it hardens to ice again.

On January 8th, his birthday, this headstone is overwhelmed by arrangements of flowers, many of them red, white and blue plastic roses. These are sent with love forever from the “Happiness is Elvis Fan Club” in Atlanta, “Oklahoma Fans for Elvis,” the “Welcome to Our Elvis World Fan Club,” based in Illinois. And there are flowers sent by individual fans: a guitar made of mums; a hound dog made of blue carnations; and a two-by-three foot piece of green felt nailed to a Styrofoam board, with ELVIS spelled out in red plastic flowers, a dove at the top, all bordered in holly, made by a woman from New Orleans who stands beside it all day long, silent, and weeping.

The other fans, defeated by loss and the harsh winter weather, wear parkas and newly-bought scarves and mittens with Elvis embroidered on them in red. A forty-year-old fan from Chicago is interviewed by a Memphis reporter who is young, female, black, as baffled as she is earnest. “For everyone of us that’shere,” says the fan, “a thousand wish they could be.” “That’s a good quote,” says another fan. “Well,” says the woman, “it’s true.” She turns back to the reporter. She says, “Coming here is the least we could do.” The reporter thanks her and turns away. “You didn’t let me finish my quote,” says the woman. “I was going to say: it’s the least we could do when he did so much for us and everybody.”

Memories Are Made of This

After taking flowers to his grave, the fans walk down the hill to the souvenir shops where they are offered cupcakes called “Elvis’s birthday muffins” by older Southern ladies, and homemade cherry birthday cake with shiny white icing.

At the Hickory Log they order hot chocolate and Dr. Pepper. They bring their scrapbooks with them. They show their pictures: Elvis in the lobby of the Chicago Hilton, Elvis at midnight on his motorcycle in Memphis, the white two room house in Tupelo where he was born. “What’s this one?” a woman asks, looking at a picture of a small country house. “That’s nothing,” says her friend, grabbing the picture back. “Just where we live in Mississippi.”

“I’m trying to find a dignified way to put this,”says a 34-year-old woman from Houston, Texas. “When I was eight years old and saw Elvis Presley for the first time I realized what a man was. I never felt anything like what I felt for Elvis, except tor President John F. Kennedy. I was with him 100 percent of the way. I remember the year he ran. In our civics class it was a big thing. Maybe he stood for the same things Elvis stood for. People knew they’d take a younger attitude toward things. To me they both had a whole lot of backbone.”

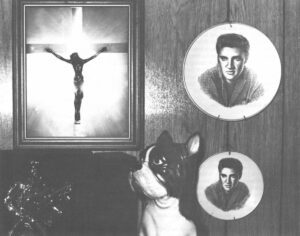

“I’m a typical Elvis fan but I didn’t worship Elvis Presley. This is really getting deep. I believe in God Almighty, and I believe that to put Elvis above him would be wrong. I don’t put him above the Lord, but as far as my love went it was deep and true and I’m not ashamed of it.”

“I appreciate what he did,” another woman is saying at another table. She is from New Orleans. Her hair is black, dyed the same color as Elvis’s. “I never once considered his body. I never could have gone out with Elvis. Even if he had asked me. I just would have liked to be his friend. The majority of fans feel that way.”

“When he was onstage something within came alive. Okay. I’ll give you a good example. When you can be onstage and all 10,000 people in the audience think you’re singing straight to them. That’s something accomplished.”

“He wasn’t just a hero. He was our dream. He accomplished something we wanted to and couldn’t. The American Dream. He started out with nothing and look what he became. Without a high education.”

“I knew him from the fifties,” says a 50-year-old woman from Birmingham. “From when he appeared at the Municipal Auditorium. My grandfather worked there. Elvis was very polite and kind and courteous to people. I even met Liberace and he didn’t impress me. But it’s strange how something just draws you to Elvis. He was a down to earth person.

“After he died I went in the hospital for two weeks. At home I live on pain pills. Here in Memphis I’m well. It’s like an inner peace you get. Once you come here you have to come back. It’s like a force within you.”

The talk continues into the evening. The stories have been told and retold so many times before. There are just women in the Hickory Log now and they respond to one another’s stories with the forced enthusiasm of a person thanking someone for a gift they had looked forward to receiving and which turns out to be something they already own.

Some faces are sweet; some, as open, blank and uninteresting as an unlocked diary with empty pages. They speculate on what life would have been had there never been an Elvis. “If it weren’t for him,” says the woman from New Orleans, “we all would have been dead people.”

There is proof for that statement, and it is found in people who live in apartments, ranch houses, and tract subdivisions, in homes with two bookshelves, one of which hold a complete, unused edition of the World Book Encyclopedia. In these homes the color television is left on all day long and is the focal point of the living room. In the bathrooms, one can find Avon cosmetics and a small wrought iron stand surrounded by pastel plastic flowers, in the center of which is a scented candle that has never been lighted.

The address of one such home is Trailer Number One of the Tex Roberts Trailer Park in Mobile, Alabama. This is the home of Mrs. Tex Roberts. She has lived here alone since 1975 when Tex Roberts passed on to a more perfect world. Mrs. Roberts is 64, slightly overweight and sturdy. She wears glasses and has short, untended iron grey hair.

Old Cowboys Never Die

The trailer is old. The walls are made of genuine pine panels. The front room is long and narrow. There is a dull green couch in the center of the room. In front of the couch, on a narrow table, is an orange plastic bowl half-filled with mixed nuts and a two pound box of Celia chocolate covered cherries. Above the couch, fastened to the wall, there is a horn from a longhorn steer. It is surrounded by four cowboy hats and a straw bowler, each encased in plastic, worldly possessions of the late Mr. Roberts.

At the end of the room there are five shelves. On the bottom shelf there is an arrangement of dusty plastic flowers. The other shelves are laden with pictures of Tex Roberts. Above the shelves a banner reads: Tex Will Never Die.

Recently Mrs. Roberts added a room to the trailer. She calls it her Elvis room. Similar rooms exist in the homes of many fans. The room contains 112 side-by-side pictures of Elvis. There is a bronze bust of him; around it’s neck there is a long yellow scarf. There are Elvis lampshades and plates, Elvis ash-trays, and a large frame encloses the complete set of Elvis bubblegum cards. There is a record player with dozens of Elvis records, especially his gospel music, the only thing that can cheer Mrs. Roberts when she is sad. Also a bottle of dirt from the groundbreaking in Tupelo of what is now the Elvis Presley chapel, and tiny dried leaves in a bottle Mrs. Roberts labeled, “Baby’s breath from Ann Margaret’s floral arrangement to Vernon Presley’s funeral. It’s in one of my antique bottles.”

Mrs. Roberts began collecting Elvis records and books when her husband took sick in 1970. She began collecting memorabilia when he died. In the morning she sits in her Elvis room and looks at his pictures. Occasionally she will say to a picture, “Elvis, you cute thing, you!” Most of her conversation is about Elvis because most of her friends are Elvis fans. “’Cept for Jackson. He’s a preacher an’ he don’t like Elvis. All that shakin’ an’ everything. He thinks it’s terrible. But his wife, she likes to read about Elvis, and if a nice story comes out about him she’ll say, ‘I’d like to see it when you get a chance.’ At home she’ll read it. But she’ll hide it under her pillow so her husband don’t see it.” In the afternoon Mrs. Roberts watches soap operas. “Since I got my video recorder, if there’s something on I don’t like: Boom! In goes an Elvis movie or Elvis concert. Don’t know what I’d do without Elvis. Can’t imagine it.

“I saw him for the first time when he was about 18 years old. When he played the Mobile Fair. You couldn’t hardly hear him because it was a makeshift affair. But you could see him.”

“I never did see him again because me and Tex we used to be in show business. We traveled with the carnival. He was business manager and I worked the popcorn stand. Originally I’m from Minnesota, up in Hibbing.”

“Tex and me we wanted to have children. Then we found out we couldn’t. So Elvis was like a son to me. That’s the way I think of Elvis. There’s one girl around here, she’s a real good Elvis fan, and she says, ‘He could put his shoes under my bed anytime’. But she’s a younger girl. Never have I thought of Elvis that way. Not in no sexy way or nothin’.”

“I just love everything about Elvis. The way he grins and jokes. He’ll say something and just look over sideways and he’ll have that silly grin. It just makes you feel happy to see it.”

“Last year on his birthday I went to Graceland and there was this reporter. From the UPI? Well, he showed me his credential. Then he said, ‘You’re here for Elvis’s birthday’ and I said, ‘Correct’. He said, ‘What do you think about the drug situation with Elvis?’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘I listen to it but I totally ignore it because nothing can change my opinion of Elvis.’”

“I remember reading where he made his first gold record. He was at his grandmother’s when he heard about it and he said to his grandmother he said, ‘Let’s go out and celebrate.’ And he took her out. To supper. For his first gold record. I just love how he done her. And his mother.”

“Once I met that Lansky who owns that fancy clothes store? And he told us how Elvis used to come there and look at the clothes and he really couldn’t afford the stuff. In one of the magazines thay made it sound so pitiful. Elvis standing outside and Lansky said, ‘Why don’t you come in and let me outfit you in one of these outfits?’And Elvis turned his pockets inside out and said ‘I got nothin’. Not a penny.’ But he said, ‘Someday I will have and when I do I’ll buy your clothes.’ And when he did, he did.”

“I just wish I could have met him. I would have said, ‘Hello Elvis’ and he would have said, well, ‘hi’. Or he might have said, ‘hi I’m Elvis Presley’ and I would have said ‘hi I’m Frances Roberts. How are you. And I’m real happy to meet you.’”

“Someone came by the other day. He said, ‘I’ll tell you one thing. They’ll never be anymore men in your life. Just Tex Roberts and Elvis Presley.’”

Like the majority of Elvis fans, Frances Roberts describes herself as “a typical Elvis fan”. This designation means, among other things, that one has achieved immunity from the stated pitfall of love, that tendency to ultimately be repelled by the precise attributes one was attracted to in the beginning. Typical Elvis fans bypass this syndrome by falling in love because Elvis was so undeniably hip, and remaining in love because he was so irredeemably square.

They love a man they never knew, a man who can thus never disappoint them, and who made it possible for them to experience passion and love combined with the reassuring knowledge that whatever hurts might accrue from this love were strictly impersonal.

Depending on your point of view, that is everything, or nothing.

©1981 Elizabeth Kaye

Elizabeth Kaye is studying the Phenomenon of Elvis Presley in American Life.