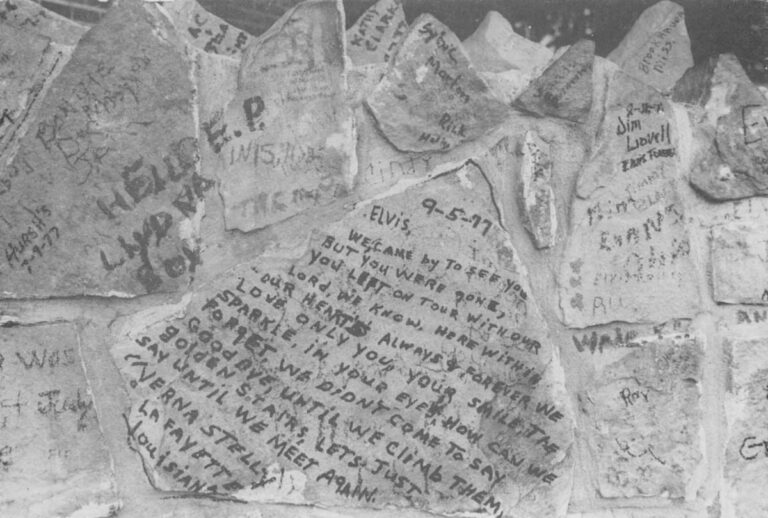

MEMPHIS, Tenn.–They approach the grave in silence. A few yards from the gravesite they extinguish cigarettes in a foot-high bucket crammed with paper cups from MacDonalds, empty boxes of film, and Whattaburger wrappers. They leave a flower or a bouquet. They say a prayer. On the way back down the hill many ask questions of the guards. How long did he live here? How many rooms in the house? Is that his horse, Rising Sun, in the yard? And still there are those who want to know: Is he really dead? Did he really die?

It is August once again in Memphis, Tennessee. Now Elvis Presley is four years dead, and the faithful come, as they come each year, to the grave of the man they adore. “One wonders why,” writes a columnist in a Memphis paper. “Ask why I’m here,” says a woman from Milwaukee. “I’ll tell you I don’t know.”

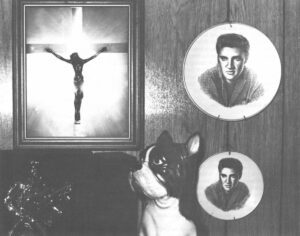

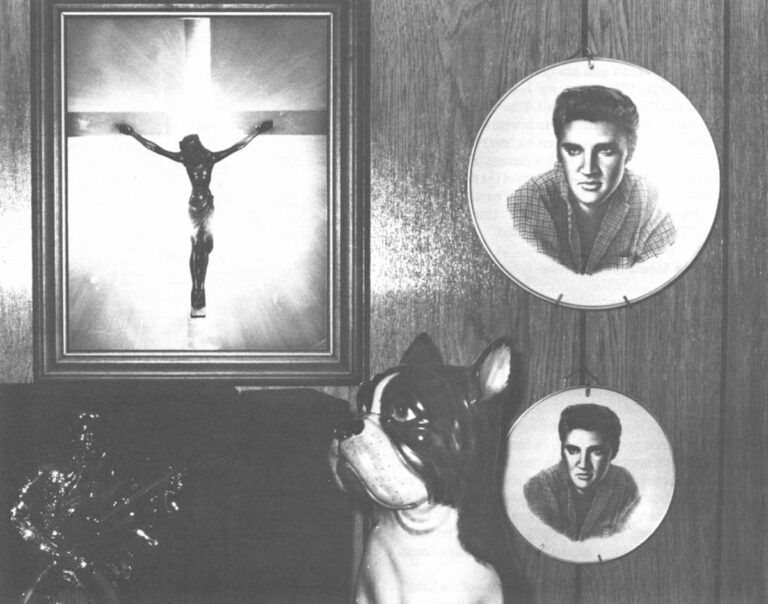

Part of the answer can be found in a precedent that grows increasingly clear, for the King of Rock and Roll has come to be perceived by his fans as a Christ-like figure, and grieving for him must ultimately be viewed as a modern day instance of how the community, bereft of its saint, behaves. In the course of this annual pilgrimage to commemorate his death, the multitudes will come more than ten thousand strong. They will observe the death and they will gather in places where they will seek out relics and artifacts, they will purchase talismans, they will meet his disciples, they will hear the Good News, and they will hope to be sanctified by being close to those who were close to him.

Jumpsuits and Jesus

Relics of the King are on display at the Elvis Presley Museum, formerly a gas station, situated just down the street from Graceland. The museum opened in February of this year, and is owned by Jimmy Velvet, who was raised by Elvis’s Aunt Lorraine, has Beatle-style hair dyed the same color as Elvis’s, and first met Elvis in the early 1950s.

Entrance to the museum costs three dollars. The three hundred items within range from the flamboyantly materialistic to the sweetly spiritual, as Elvis did himself. There is the green jewel-encrusted robe he wore for a single time on New Year’s Eve 1976, a Mercedes limousine, his crucifix, and the velvet-covered bed from his California home. There are several of his guns, and four vials of pills including one of benadryl prescribed for Elvis by the infamous Dr. Nick, personal physician to the King who is currently charged with malpractice for dispensing incredibly vast quantities of pills in Elvis’s name.

There is also a small portrait of Jesus kneeling in prayer–bought by Elvis for his parents when he was 15. He had saved a week’s pay to buy it, and later cited it as his personal favorite of all the gifts he had given them, to the extreme approval of many fans.

Four women are clustered around Jimmy Velvet who is holding up a very special relic, the purple underpants Elvis wore beneath his Burning Love jumpsuit. The women are middle-aged. They are squealing and jumping up and down. “You see they’re the same color as the jumpsuit,” says Jimmy. “And they’re made by Munsingwear.” The women stop dead. They stare at Jimmy. Finally one speaks. “Munsingwear,” she says sharply, “We thought he wore Fruit of the Loom.”

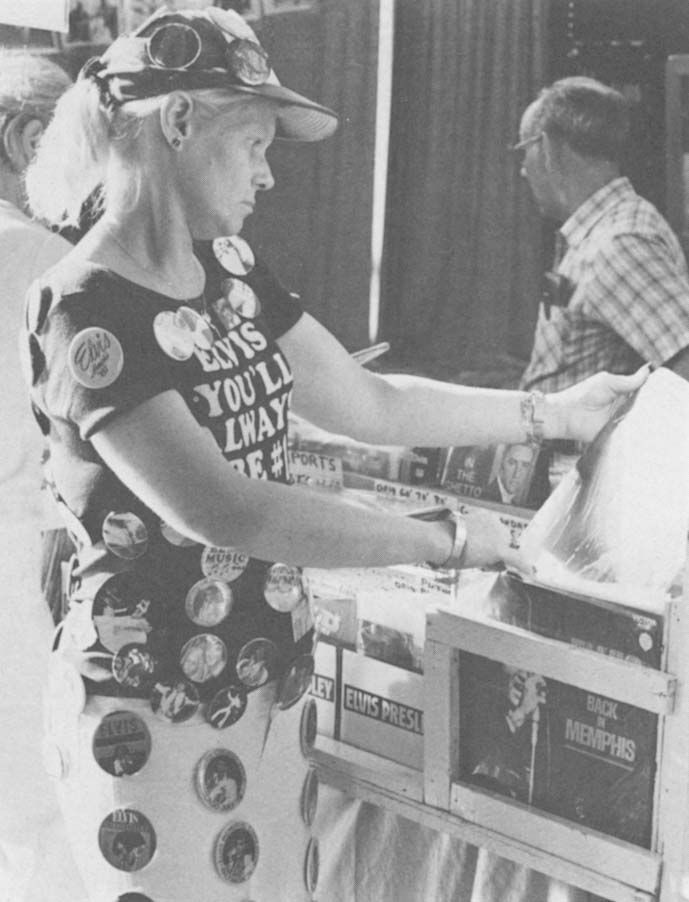

Talismania

At ten in the morning, August 13th, 1981, the four day Elvis convention begins at the Cook Center in downtown Memphis. There, 80 vendors from across the United States gather to sell Elvis talismans in a room the size of four basketball courts lined with 80 tables. The four-day convention is run by Gray Line Tours, who leases tables to vendors for 250 dollars a piece, a sum that entitles them to sell their wares from ten in the morning until ten at night.

Admission to this room costs Elvis fans six dollars a day. Inside they watch video tapes of Elvis and purchase Elvis plates, busts, pictures, records, calendars, or a 17-jewel watch on whose face Elvis’s own visage appears and disappears 2,800 times a day.

All day long, Elvis music emanates from speakers set in the four corners of the room while Elvis fans buy Elvis Christmas tree ornaments and Elvis decanters. “I’m just a puppet,” sings Elvis, “you can do most anything with me.” A white-haired woman from California is showing her purchases to two fans from Chicago. “I got a lampshade, see, with Elvis on it, and a picture of him and Linda Thompson getting on his plane. An’ a picture of the plane, an’ a bank. See, you put the money right here, through his head. When I get home I’ll put them straight in my Elvis room. I painted it red, white and blue, you know, and the carpet is beautiful blue high-low pile. I have all my pictures in it.” The woman’s voice becomes louder as she talks faster and faster. “And all my records. Bootlegs by the galore. And a case with the scarves he gave away onstage. Not that Elvis ever gave me any scarves. My husband bought them.” Now Elvis can be heard singing “Solitaire,” one of the last songs he recorded. “There was a man, a lonely man,” he sings. The woman becomes quiet. She listens. “A heart that cared, that went unshared,” sings Elvis. The woman sighs deeply. The energy and air seem to leave her body. “If only I could have just once touched him,” she says, “I never did get close enough for that.”

Those who qualify as disciples of the King are the singers and musicians who worked with him onstage, and the 13 men who came to be known as the Memphis Mafia, who lived with Elvis, worked for him in the role of go-fers and body guards, and were, in effect, paid companions who went along for Elvis’s 23-year-long ride, the mythic Great American Ride that includes lots of money, women, drugs, fast cars, and the illusion of total power. Of this latter group most had been Elvis’s high school friends. Taking care of the King and catering to his whims was the only employment they had ever known and it was not exactly work that trained them for other endeavors. When Elvis died, many maintained their association with him by writing Elvis books and publishing Elvis newsletters. One such book is Portrait of a Friend, written by Marty Lacker, and published in three different book jackets, a marketing device that has successfully induced numerous fans to purchase three books that are exactly the same. Like most books about Elvis, Lacker’s is concerned with Elvis’s drug problems and other gossip. “I wrote the book for two big reasons,” Lacker likes to explain, “The number one big reason was to set the record straight. The number two big reason was I needed the money.”

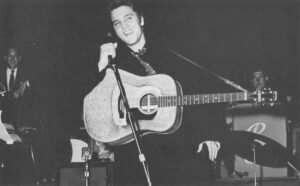

Another Elvis book is D. J. Fontana Remembers Elvis. Fontana was Elvis’s drummer from 1956 to 1968 and looks like a cohort of Nathan Detroit. His book consists of photographs of Elvis on the road in the 1950s.

Late one night D. J. comes to the Hickory Log, the 24-hour cafe fans favor. He is armed with 20 copies of his book, two friends, a six pack of beer and a big smile. Within five minutes the twenty copies have been sold for ten dollars each. Fans now line up at D. J.’s table. D. J. smiles at them as they present their books for him to sign. One of his friends hands him the book purchased by the owners of the Hickory Log. “Sign this one to Bonnie and Hobart,” whispers the friend. “Bonnie and Hobart?” D. J. mutters, still smiling, “Who the hell are they? Sounds like a couple of germs.”

Outside the Hickory Log, later that evening, D. J. talks some business with Danny Mayo, an extremely overweight young man and owner of an Elvis artifact, a Cadillac station wagon Elvis bought in the mid-1970s. Danny is paid to display the car at dealerships across the country, and would like to pay D. J. to go on tour with it. D. J. is agreeable. “We’re doing so great you can’t believe it,” Danny tells D.J. “This very weekend we’re in Newark, New Jersey and we’re gonna be on WNBC-TV.”

This conversation is overheard by Tony Russo, also extremely overweight and a self-described Elvis Fan who can be found at the Hickory Log pretty much every night of the year. Russo moved to Memphis from Florida after Elvis died, and made quite a name for himself selling items to fans which he claimed once belonged to Elvis, but which hadn’t, like the purple shirt with puffed sleeves he sold a 60-year-old woman for 850 dollars, money he returned only when threatened with being run out of Memphis.

Pieces of Elvis

Tony Russo is now the owner of an artifact similar to Danny Mayo’s: the white Cadillac Elvis gave his karate instructor Khan Rhee. A year or so ago, Russo made a deal with General Motors, and now displays the car at G.M dealerships along with one of Elvis’s guitars, and several of his karate outfits, all to a musical background of Elvis singing. Late in the evening Russo pulls Mayo aside.

“I got an idear for your business,” he tells him. “It outclasses D. J. Fontana by a mile. Elvis’s Aunt Lorraine. Get her with the car. Course I don’t know what you can get her for. If you want her, she goes right.”

“How old?” Mayo wants to know.

“Sixty-two,” says Russo. “But don’t worry. She can out-boogie your ass any night.” A fan taps Russo on the shoulder.

“Excuse me,” she says, “but can you tell me where you’ve shown your car?”

“Name a state,” says Russo.

“Wyoming,” says the fan.

“No,” says Russo.

“California.”

“No.”

“Nevada?”

“Listen,” says Russo, “we haven’t actually gotten west of the Mississippi yet.” He turns back to Danny Mayo. “Here’s why you want Lorraine. Know what she brings with her? A brooch. Elvis gave it to her for Christmas. Conrad Hilton gave it to him. It’s maybe six inches across. 18 karat gold. Eighteen is the next step from solid, right? I wouldn’t know the penny weight, but that sucker is heavy.

“It’s got ELVIS written in 52 diamonds, and a 20-dollar uncirculated gold piece embedded dead center with 12 big diamonds around that. Lorraine puts it on her neck and people take pictures of her. It’s worth a hundred thousand bucks. How you gonna top that? D. J. Fontana can’t top that. Nothin’ can. For the money.”

At two each afternoon three Elvis disciples come to a booth at the convention center to sign autographs and meet the fans for an hour. Kathy Westmoreland is small, attractive and did Elvis’s high voice singing. After he died she received more than a thousand letters a week for two years from people who wrote that Elvis had promised them a house or a car or jewelry or money, and would she please help them get it. She continues to get at least 20 such letters a week, and they continue to upset her, though not nearly as much as do the fans who ask her to autograph the picture of Elvis in his coffin that a cousin of his took and sold to the Enquirer for 100,000 dollars.

Also signing autographs each day were J. D. Sumner who sang the bass parts of Elvis’s songs and is almost 6’6″ tall. Also Charlie Hodge, 5’2″, who met Elvis in the army and from then on trimmed his sideburns, dyed his hair with L’Oreal Preference Dark Black, and sang harmony and played guitar with him onstage. Charlie lived at Graceland as long as Elvis did, and then stayed on six months longer for when Elvis died it did not occur to him to leave and he had no place else to go. Now he is the featured guest at Elvis conventions across the United States and in Europe. “Next month I go to Holland,” he is saying to a group of fans who regard him with adoring eyes. “They’re unveiling a statue of Elvis. They haven’t cast it yet, but they sent me a picture of the clay model. It’s the best one yet. Even better than the one in Vegas.”

The three disciples are seated behind a table. Fans swarm around. They shove their autograph books at them. “Put to Toni with an ‘I’ “, “Write: ‘to Verna’.” They focus cameras. “Can I have a picture made with you Kathy?” “Stand here J. D.” “Say ‘Cheese’ Charlie.” They push each other. They push the honored guests. As the hour slips by the atmosphere at the booth becomes increasingly vicious and venal and finally reveals nothing Nathanael West did not know all about some forty years ago.

After the autograph session the disciples spread the good word at question and answer sessions in an auditorium which fans attend for the price of an additional six dollars. Charlie, J. D. and Kathy sit onstage. Fans ask how Elvis’s daughter is doing, what was his favorite gospel song, what was his mother really like?

“I know he was a very religious person,” says a woman in an Elvis the King T-shirt, “but I’d like to know if he had a personal relationship with Jesus.”

Take It To The Lord In Prayer

“Absolutely,” says J. D. “He read the Bible every day,” says Charlie. “He was a true Christian,” Kathy says. “I spent more time praying with Elvis,” says J. D. “than I have with anyone else.” “We all prayed with him,” says Charlie. “He was a good Christian man.”

There are three talk sessions and in one form or another this topic is raised at each of them. The answer is the same each day, and comprises each session’s high point, and at the words “good Christian man” the audience invariably breaks into wild applause.

At the end of one of the sessions a woman walks up to Charlie. “Excuse me,” she says, “but weren’t you Elvis’s right hand man? Weren’t you always there?” Charlie nods agreement. He says, “Elvis was my best friend.” “Then could I touch you?” says the woman. Charlie smiles somewhat shyly. He puts out his hand. He is wearing a gold ring that Elvis gave him. The woman covers his hand with hers. On her fourth finger is a gold ring with a picture of Elvis in its center. Their hands meet. Within the grasp of the two clenched hands the tiny face of Elvis remains visible. The woman lets go of Charlie’s hand. “Thank you,” she says. “God bless you,” says Charlie. The woman says, “He just did.”

The American Heart Association

Elvis Presley’s body was originally interred at a mausoleum near Graceland. In a petition to have the body removed to the estate, his father, Vernon Presley, told the court that threats to steal the casket were causing him intolerable mental and physical anguish. The court ruled in Mr. Presley’s favor in the fall of 1977. Since then, the pathway to the burial ground has been open to the public.

The gates open at nine in the morning each day but Monday. They are closed again at four. In the intervening seven hours, each day of summer, 1981, six thousand men, women and children walk the quarter mile hill to where the earthly remains of Elvis Presley are buried. The flow of human traffic on the hill is constant. Opposing lines are formed by those nearing the grave and those leaving it. The lines resemble crowds on the up and down escalator of a busy department store.

On the 14th of August a portion of the interior of the King’s estate was placed on view for the first time. The decision to open the building that houses his racketball court was made by Priscilla Presley, former wife of the deceased, who left Elvis in the winter of 1972, and whose leaving is commonly believed to be central to his subsequent decline into drugs and depression.

Now, Priscilla is one of three executors of Elvis’s estate. Her daughter is Elvis’s only child, and his sole heir. Elvis generated 4.3 billion dollars in his lifetime, but a year after his death there was a fractional 7.6 million left. Of that money, three hundred thousand dollars a year has gone into maintaining his grave as a public shrine. After leaving Elvis, Priscilla had opened a boutique in Beverly Hills, and with the opening of the racketball court she applied her knowledge of the retail business to devise a truly unique way of keeping her daughter’s money from being further depleted.

The court is in a wood and concrete building separate from the main house, and behind it, about fifty yards from the burial site. Once, in addition to the court itself, there was a lounge area that included couches, numerous leather chairs, and a well-stocked bar. Now the chairs and couches have been removed. All that remains is the empty bar, a single leather bar stool, and the initials EP made of wood and hung on a wall. The racketball court itself is now covered with a green rug, decorated with five ficus trees and three display cases and is a jewelry store.

The jewelry in these cases is marketed under the name Celebrity Memorabilia, and are true Elvis relics, for this is jewelry fashioned from tiny bits of stone, wood, and metal that come from the California home once owned by Priscilla and Elvis. Proceeds from its sales will go to the estate, to the upkeep of the grave and the American Heart Association, in undisclosed percentages.

The display cases contain gold-plated leaves from the trees of the estate. There are coasters made from threads of fabric that once were part of the living room draperies. There are little plastic bags of sawdust from the oak parquet floors, which can be kept in specially designed gold lockets. There is also a gold nugget key ring which sells for 24 dollars and comes complete with a statement of authenticity from Priscilla herself, as do all items in the line. “Inside this radiant 24 karat gold electroplate exterior,” it reads, “is something more precious than gold. The heart of this nugget is an actual piece of the natural stone from the living room wall of the Beverly Hills estate of Elvis Presley. Encased in 24 karat gold this natural stone shines with an outward beauty that matches its memory-laden inner meaning. Anyone will be proud to use this beautiful gold nugget bearing the true touch of the legend.

“But please remember the supply of authenticated memorabilia is limited. Once exhausted, there will be no more.”

The jewelry on display here is actually sold at a shop across the street from Graceland, since the estate itself is not commercially zoned. Nonetheless, hard sell is the name of the current game at the racketball court, where fans are encouraged to fill out cards with their name and address, and leave the cards in a box conveniently located on the King’s bar, so that they may be sent “thank you notes” for coming to the court, notes that will also include a catalogue of the jewelry and appropriate mail order forms. Additional catalogues are handed out as fans walk through the exit door. Each is presented by a woman who says, “Buy a piece of Elvis’s love.”

The very first Elvis relics were sold back in 1956. At that time, Elvis was shown a green pencil with his picture on it by the first of the big time Elvis merchants. He had looked at the pencil, then at the merchant. “Can they really sell this stuff, Mr. Saperstein?” he had said. The answer of course has been a resounding Yes, and the business of Elvis relics is now worth 40 million dollars a year. Since their inception these relics have existed to make fans happy and to prove the overwhelming wisdom of the Mencken dictum that no one ever went broke underestimating the American public, and it should consequently surprise no one that Celebrity Memorabilia sold briskly all weekend.

Love All Around

The preferred staying place of the Pilgrims who come to Memphis in August is the Days Inn, a mile from Graceland. It is four stories high and has four hundred rooms arranged in a three-sided structure. By the 15th of August, the picture windows of each of these rooms were covered with Elvis pictures attached with Scotch tape and facing outward, and which made the Days Inn into a gigantic Elvis collage.

Inside the rooms, Elvis fans shared their scrapbooks, pictures and memories. Some sold photographs of Elvis from displays arranged on twin beds.

One room was occupied by Ethel Peters, 62 years old, of Batavia, Ohio who came to Memphis with her daughter and granddaughter who are also Elvis fans. Ethel Peters is small and grey-haired. When she speaks of Elvis her face becomes radiant. “I’ve loved him since the Ed Sullivan show in ’56,” she says. “Such a nice boy! Such beautiful eyes! If it weren’t for him, I’d go crazy sometimes.

“I live with my youngest daughter, and she talks on the phone to her friends. I get so lonely, so I made a tape of Elvis songs off my albums. It’s got all my favorite songs. When my daughter gets on the phone I get in bed, put in my earphones, and listen. Golly Pete, we all just have a love for him that we can’t express.

“I have about twenty Elvis pen pals I write to about Elvis. That’s how I spend most of my time. You tell me now: most of my pen pals are about 33. Now how many 33-year-olds would write an old lady. But it doesn’t matter with Elvis fans.”

Prior to coming to Memphis, Mrs. Peters and her family stopped in Nashville to see the Elvis exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame. “It wasn’t so good,” says her daughter. “Just 18 minutes. Three minutes each of the television shows he done in the fifties.” “Oh but that first one,” says her mother, clasping her hands together. “It was just like the night I first seen him. Such beautiful eyes! He’s brought me so many friends! He just throws love all around!”

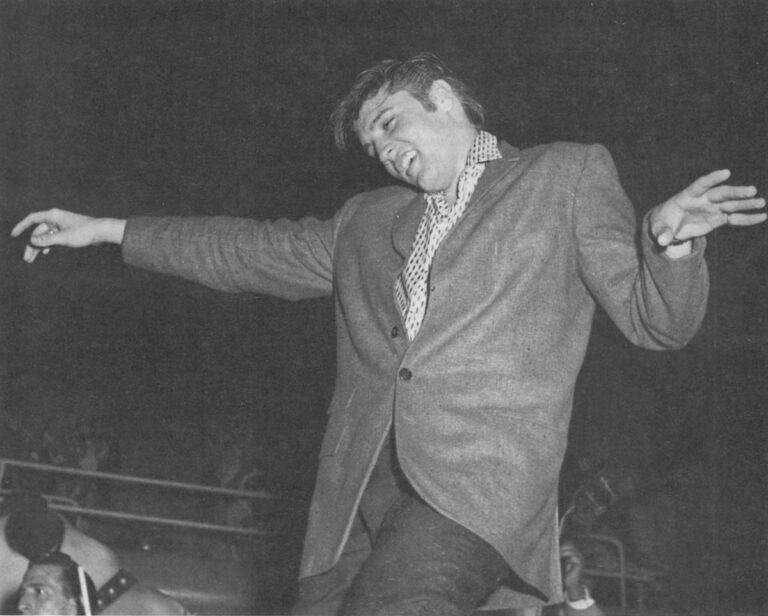

In another room at the Days Inn there is a 34-year-old woman from New Jersey who calls herself Frankie, and her daughter who is 17. Frankie wears jeans, a T-shirt and 151 Elvis buttons. Often, she is mistaken for the fan known as “Buttons” whose particular collection of Elvis buttons is fastened to a white jacket and so vast that when Elvis himself noticed her at a concert he had said, “Either you’re crazy, or I’m seeing things.”

By her own account, Frankie attended 846 Elvis concerts. She left her children at home with her husband and raised money for the trips by selling all her jewelry including the strand of pearls she got for 8th grade graduation and her wedding ring. “My husband used to tell me I was sick,” says Frankie. “I told him if I was I never wanted to get better.”

Frankie became an Elvis fan in 1966, after seeing Elvis in his white swimming trunks in the movie “Blue Hawaii.” “I fell in love with him,” she says, “but not in a female sort of way.”

“Oh, yeah,” says her daughter, “with a big life-sized poster of him over your bed.”

“Hey,” says Frankie, “I’m a normal, red-blooded woman and he turns me on.”

Frankie was divorced by her husband in 1975, two years before Elvis died. The charge was extreme mental cruelty, and evidence offered in the divorce papers was, in this order: 1) failure to cook breakfast and to perform other wifely duties, and 2) excessive devotion to Elvis Presley.

Carrying On

At midnight on the 15th of August fans gather at the Graceland gate as they do each year. In the first minutes of the 16th of August more than two thousand men and women light candles, and then sing. As they always do, they begin with “How Great Thou Art,” a song Elvis used to sing to the Lord, and which they sing to him. Their faces are sad. Many wear T-shirts that read, “Elvis didn’t die, he just moved to a better town.”

The singing lasts an hour. While they sing, some fans believe they see Elvis’s face etched in the leaves of the Graceland trees. Some think they see his face passing by in the clouds. Some think they see his shadow steal across the pavement. “Look, there’s his face,” a woman says to Frankie, indicating the leaves of a sycamore. “Oh come on,” says Frankie, “He’s not in the trees.” She shuts her eyes. Tears slide down her cheeks. “But I can see him.”

Late that night at the Hickory Log fans discuss charities they have set up in Elvis’s name to carry on his good works. They talk about the Elvis Presley burn center to be established at a Memphis hospital. They talk about the Elvis Presley wing to be built at a children’s hospital in Atlanta. “When I’m driving in my car,” one fan says to another, “If I let someone into traffic, I’ll tell myself, ‘I just did that for Elvis.’ “

A man overhears her. He smiles and shakes his head. “The last time this happened,” he says, “was two thousand years ago. And this time it’s getting better press.”

©1981 Elizabeth Kaye