April 29, 1973

The Narrowing Down – Part I

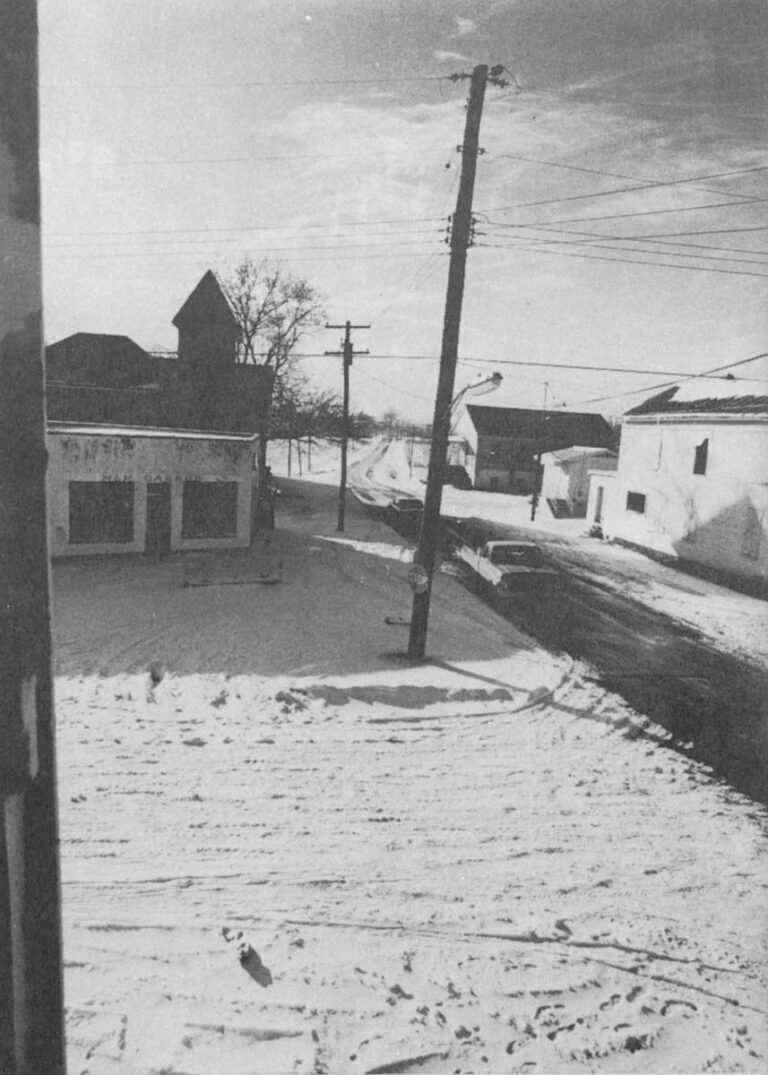

January comes to New Burlington as stealthy as old grief, known only by the idle spin of pages under Don Collett’s calendar portrait of Lovely Lillian, gazing insouciantly through the mad march of another year. Collett’s Hardware has moved now. Ronnie Grooms’ grocery store is gone. Wren Muterspaugh’s barber shop has been gone, and so has McClure’s Garage. Mrs. Louie Wills, at 94 the village’s oldest resident, has moved to the country, but it exists only in her mind’s eye. The preacher comes on Sundays still, to teach the natives shame, but there is less comfort now in such strained ritual. In January, the snows come to reclaim the village.

January in New Burlington is a virtuous month, all flint and pious starch. Its arrival is known not so much by the calendar as by the way Vernie Brewer tells time in his fields — by the texture of time itself. It is something a man understands in New Burlington and no where else but a place like New Burlington. It is a virtue not paid court to by the trend-setters and the cult-watchers, and if the people of the village understood the complexity of such knowledge, they would guard it as well as their simple silence does.

January here is like a church. It forces a man to live between the narrow walls of his life. It is a month that bleaches him out, reveals his sources and substance. It tests his temperament. January is penance for the excesses of the other months. It is a hard month, long and direct and bonecold and uncompromising. A man may fit himself to summer, but January bends a man to her. It is the silent, cold heart of winter, the time of a great narrowing down. Even the passage of a man’s soul pauses in this great, bleak month of new beginnings, and a man considers nature because of the very force of it: at no other month is he so removed from it in spirit, so close to it physically. He is thrown against his origins. January’s snows cover a multitude of man’s sins, then with the melting, reveal them in a foreshadowed perspective that only heightens the sordidness of them, a lesson all of literature gives only those already blessed with knowledge: beauty is transient. Life is transient. The earth itself, in its slow wheel through dying centuries, is transient. All men are pilgrims, footsore and petulant in recognition of a failed paradise.

The Narrowing Down – Part II

Graveyard Road is as tranquil and removed from the chaos of automobiles as its name implies. It has an inauspicious beginning off the main highway a mile and a half north of the village, then circles discreetly through New Burlington farmland, turning from tar and gravel back to dirt so suddenly and without warning that for a moment it is hard to remember: which was here first, the ground or the gravel? Disappearing momentarily in a covered bridge over Anderson’s Fork, it ends unobtrusively beside the graveyard itself. The graveyard is on a small hill looking into the slight valley and the heart of the village a half-mile away, revealed by the season. The villagers have been told that the water from the lake project will not disturb the graveyard, but they are not secure in this uneasy knowledge. In the summer, tufts of Bermuda grass will grow in the untraveled center of Graveyard Road’s single paved lane. In the winter, the driver of the snowplow slows when he is past Vernie Brewer’s farm because he has to turn around at the covered bridge. It is a strange incongruous little road, almost perfect in some kind of precarious balance between the gently rolling farmlands stretching away on either side, and the technological forces of city and suburb stalking New Burlington’s invisible perimeters like some dark army massing at her borders, awaiting only the yet uncaught signal to begin a final, terrible assault.

At a sharp turn and a crest, just before the road slopes downward for several yards to Brewer’s farm, the forces of the past seem, momentarily, to be winning. There is the road, but what is tar and gravel when Bermuda grass can dislodge it? There are electrical lines, but in the distance they are lost in a splendid infinity of forests and farmlands, not factories. Forests and farmlands deny factories. There are telephone lines, too, but in the January air as sharp-edged as a woodsman’s ax they sing like a chorus of harpies scurrying breakneck from pole to creosote pole. Somewhere miles above, in a sky so deep as to be painful, a single-engine plane drones lazily, but it too, can be reckoned with. It is not here in force.

A boy growing up in New Burlington might have felt all these things, and been oppressed by them. It is the nature of the child to stand half-rooted to his youth, like an errant, unshaped plant twisting toward the sun, swayed by a monumental sense of life to come. Here, he could take measure of the sky and the earth. In the winter, ice falls off the trees like thunder. The streams groan. In the spring, he could hear the fields ripen, smell the grass growing, feel, even, the slow, indolent spin of the earth beneath his bare feet.

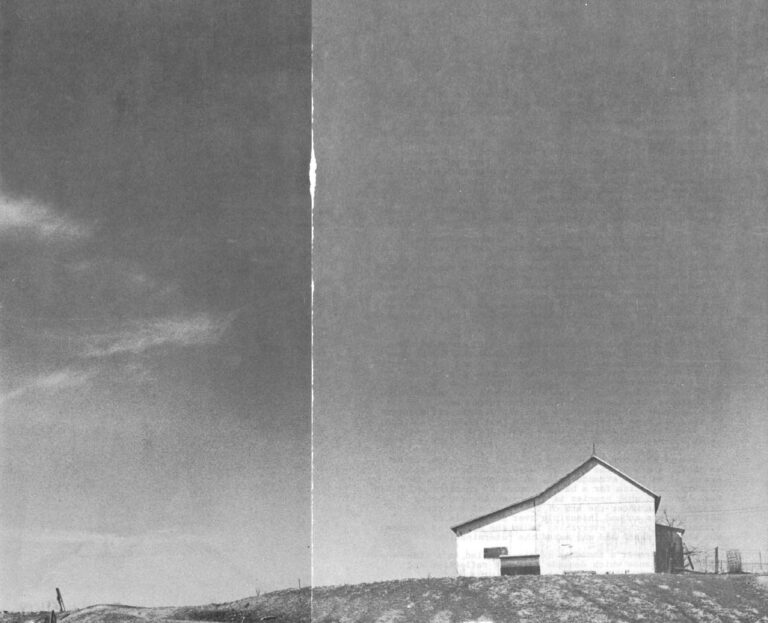

The farm Vernie Brewer has rented for the past seven years lies in the shallow valley like a timeless fresco etched out of the gelid landscape by the hand of a master. The road going by is no more than serviceable, so minor as to be largely unnoticeable. A man passing his time in the keen isolation of a New Burlington winter might, after several insular weeks, wander to the front of his place and marvel at the existence of such a road, lying coiled across the countryside like some strange fossil long since turned to stone. He would have need of the road only in the spring, really, and until then it would occupy whatever form it pleased.

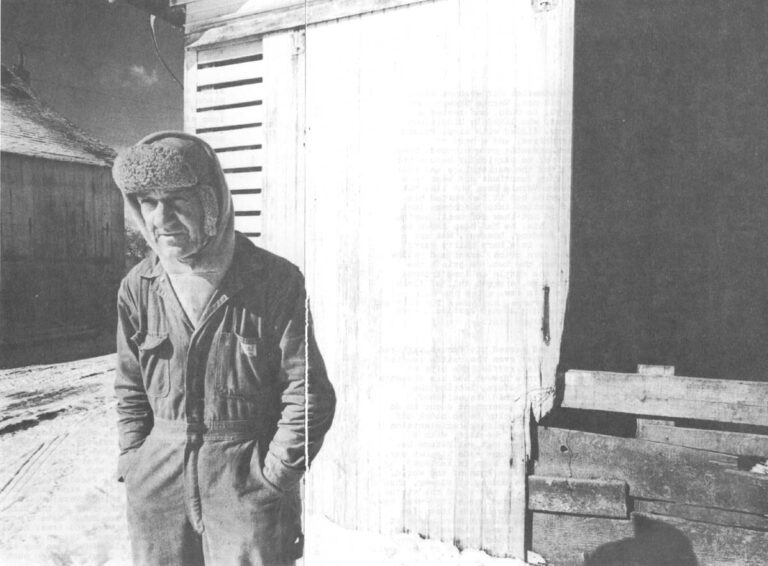

The barns lean over the two-story frame farmhouse in that particular kind of offsetting architectural grouping of house, barns, and yard known to an earlier time, where the posture of timber and space acknowledged a bond between man and his buildings, his livestock, and the very space around him. Its proximity is a pleasant, symmetrical one, and it is not found much today because the virtues of simple folk have been tampered with by style and expediency of another nature, the nature of brick veneer and quick construction, tight lots of space and the zoning of the land-merchant, all to an unnaturalness not present in Vernie Brewer’s lands. The livestock barn is high and lofty with shuttered windows and a rough, chipped texture which is not unlike the landscape of Vernie Brewer’s face, slim and creased and, like the barn, largely impervious to the January wind. There is not much romance to Vernie Brewer’s life. It has been hard, but uncomplicated, full, but inarticulated in the way that certain men live with knowledges past the ear and mind and hand of men less attuned to natural rhythms and cycles, yet the differences between them go unstated, except in the sense of a man’s presence. It is a difference between men that is narrow and passing today, because most men desire a different grace, and they are swayed largely by style and the contemporary moment, not substance. Vernie Brewer is not a contemporary man.

Born in Kentucky, he spent most of his life as a carpenter and a farmer. If he built nothing that was particularly remembered, then neither did he build anything that he found particularly offensive, and so what if it turned out to be a glue factory, it was the building itself that counted, what a man did with his hands. Were the hands of the man who fitted the joists of a glue factory marked by the factory’s pollution? Were the hands of the man who split the atom stained by Hiroshima? Who was to say such a thing? Vernie was a carpenter in Florida during the great land-rush of the Fifties and it suited him. As long as a man could have a part of something that seemed open and outward and free. He didn’t have to live in those reckless homes, thrown up so furiously a man wondered if they all might some day sink out of existence in the sandy soil, leaving not so much as a shingle to mark their passing.

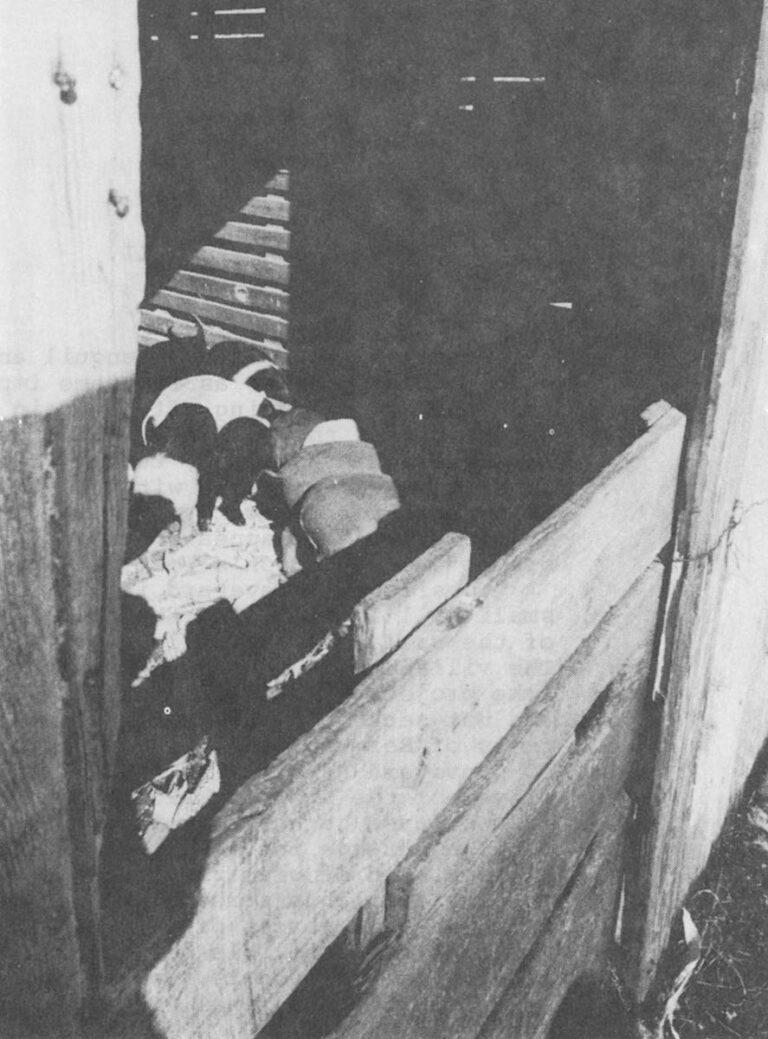

A decade ago, his wife homesick for seasons which changed and neighbors who did not, Vernie Brewer came back home, back to the north, to Ohio, and rented a farm from its absentee owner, who lived in Middletown. The farm is a livestock farm, filled with pigs, Poland Chinas and big, coarse Berkshires, and a herd of Charolais cattle, fifteen-sixteenths pure-blooded. They are rough, uneven creatures of no particular beauty but they grow quickly and well for the marketplace and that is why they are here. The farm functions are kept to a minimum in the winter because Vernie does not like the cold. His wife disliked Florida but it had suited him. The southwestern Ohio cold settled into his bones just after Thanksgiving and he did not thaw out until haying time. Sometimes, because of this, he had been known to feed as late as 8 a.m. The feeding, however, was not a great chore. The hammermill is in a barn thirty yards from the cattleyard and the corn cribs, great and yellow as a king’s vault, are between the two. He grinds the ear, cob and all, and feeds the cattle in long troughs worn smooth by the cow’s tongues, a great roll of flesh so rough as to lick a man’s skin raw, after the salt on his arm. Vernie, like most farmers, has names for each and can tell them all apart, something always mystical, even aboriginal, to the occasional urban visitor.

When the engineers came and marked his fences with red and yellow ribbons, portents that even the cattle reacted to by sudden panics when the wind ruffled the bits of plastic on the barbed wire, Vernie Brewer had his thoughts about it, then went on as he had before, letting the seasons dictate his movements. He told his neighbor, Everett Mendenhall, that what the government ought to do instead of running off folk to the city is to block off some of those bought farms and put welfare recipients on them. “Make ‘em make their own way,” he said, with a weathered tilt to his face which was not solicitude but the angle of honest arrogance at having made his own way, at having paid hisdues. He had been born in Kentucky, and had been to Florida, and had seen some of the world, and if he did not rage against the coming of clamor, then he had seen how the world worked out there and the virtue it taught — could it have been, instead, venality? — was how to adapt. There were times, sometimes in the long, low valleys of a winter night, that he thought more about it, and sometimes his thoughts almost formed themselves and clamped down on something that troubled him but whatever it was, like some slippery fruit at the bottom of the bowl, slid away and eluded him.

“Greed,” he said finally, with a pronouncement as clipped as doom. “This is all about greed. They said they’re doing this to save Morrow and them little towns above the Ohio. Well, I got news for ‘em. They could buy Morrow and move it for all the money it’s costing ‘em to do this to New Burlington. They’re gonna build them a big lake and develop the land. Some people’ll sell their souls to torment for $5. Before I came here, somebody was working on that barn and found $50 in the framework. They went through the entire barn looking for more money, and then they went to the house. It’s a different house now because they rebuilt it, but then it was a number one, triple-A house, three-brick deep walls and they tore it down brick-by-brick looking for money they never found, and that’s what’s happening to New Burlington.

Soon, Vernie Brewer will have to make a decision. He feels he is too old to keep on farming, and he rails against factory work. “I got three brother-in-laws in a paper mill in Middletown working swing-shifts. No money’s worth doing that. I couldn’t work there to save my guts. At night I want to be in bed asleep. In the spring, sometimes I’ll plow all night, but that’s my shift the way I choose it, it ain’t no graveyard shift in a factory.” So Vernie Brewer is not a contemporary man, but his inarticulated sensibilities are not enough to protect him from a contemporary life.

The malaise that comes on a man at odd, troubled times is as primitive a response as that made by the lowest form of animal sniffing his way past the sickly and the faltering toward the strongest member of the species. The ancient pull is to survive in recognizeable form, a process of accentuation. The malaise tells a man mutation is the price of weakness, and that he will not recognize himself in his very processes if he consorts with his weaknesses. Movement is crucial, time existential. And if that ancient pull does not feel safe, it at least feels real, and a man’s very nerve endings touch aliveness.

But if that man is of this time and this place, if he is at all a man of the 20th century, what then? Vernie Brewer lives in a strange void, an immigrant in his own country, searching for a basic grammar of instinct which has been lost. Of what species is the crippled prey being dragged along under the arm of this bear of a century, nerve endings rubbed insensible over the rubble of transition? Perhaps everything is in the moment of release, but when is that? And who makes the determination?

Vernie Brewer’s thoughts remain troubled in a time and circumstance which demands rest for reflection and an essential privacy. In the absence of rest and privacy, a scene registers itself in Vernie Brewer’s mind. “I think a lot of getting back to Florida,” he says. The picture postcard confronts known territory. But if New Burlington will soon sink below chimney-level, who can say that the homes in Florida are not already gone? The memory, disturbed, finds only twisted geography.

Like winter ice melting for the revelation of things good and bad, credibility thaws a man’s hope. Vernie Brewer is neither a species safe nor lost. He is a man revealed in a crucial moment of evolution.

The Narrowing Down – Part III

It was a hard winter in New Burlington because it came late. Autumn melted into Indian Summer and the trees flared as brilliant as the town’s failure. A reasonable warmth remained through December as if to stay the deep and natural chill of loss. It was gentle, lulling, and treacherous. The snow and ice came in January, late, and if New Burlington had not kept memories of other winters like this one, the village would have felt betrayed. In late January, only the post office was open. Three families remained in New Burlington, and Lawrence Mitchner, who waited for the water. “Big changes coming,” said a man at the service station on Highway 42, four miles west of New Burlington, sweeping his free arm in an arc over the land the water was to cover. “People and buildings and big automobiles. They’ll be boats and stakes and string, and caterpillers to come, and houses with carpets and clotheslines and birdbaths. Five years from now, nobody’ll know it. Me, I’m going the other way. I’m going to Idaho. I hear there ain’t enough people to bother anybody in Idaho.” His tone was sure, as though he were certain of an audience able to catch the inaudible measure of unspoken rage, and understand. In New Burlington, in front of a house of boarded windows, a dog howled at midday.

Received in New York on MaY 7, 1973

©1973 John Baskin

John Baskin, on leave from the Wilmington News-Journal in Wilmington, Ohio, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow, supported by a Ford Foundation grant. This article may be published with credit to John Baskin, the News-Journal, the Ford Foundation, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.