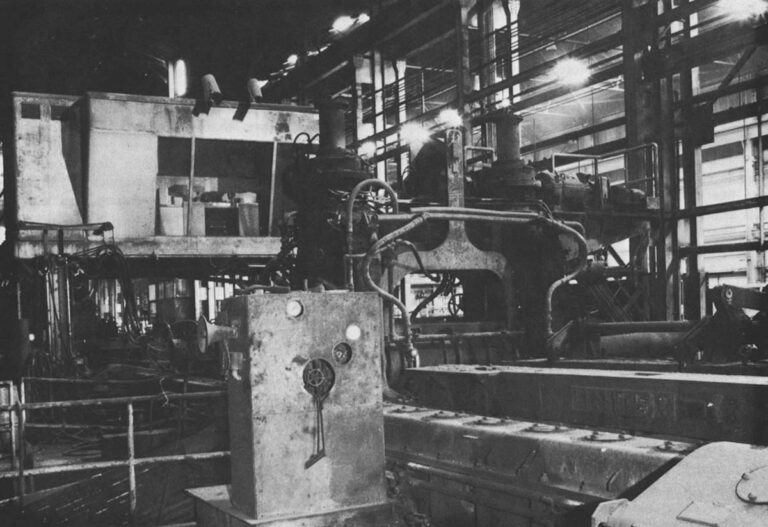

Chilly drafts of wind pour through cracked windows and holes in the roof of Bethlehem Steel’s tool shop. The interior looks like life had suddenly stopped, as though men had simply abandoned work stations and left their equipment to rot. Pigeon dirt covers rolling tables where streams of steel billets used to flow. In nearby sheds, hundreds of dies, once meticulously cut by skilled craftsmen, sit rusting and neglected because someone else’s dies are now shaping this nation’s tool steel.

It is no longer possible to suspend disbelief of steel’s distress once you tour an integrated steel mill, as I did at Bethlehem Steel’s home plant. At least half of the five-mile facility resembled a wasteland. Under decaying roofs, piles of brick rubble were all that was left of bung furnaces where since the early 1900s thousands of workers once heated, chipped and rolled strips of steel into shapes. Giant crane-borne buckets lay rusting among strewn, disconnected motors at the steel foundry where as late as three years ago teams of hard-hatted men forged 250-ton stone crushers or big turbine castings for General Electric Co. and Westinghouse Electric Corp. A half dozen silent locomotives that do not appear to have moved in years sat frozen in their tracks, grim symbols of an industry being passed by time.

As editor of the newspaper in Bethlehem during steel’s troubles, I can almost recite the steady litany of closings since 1977. First, the steel fabricating shops, then the old bar mills, machine shops, and blooming mills. In 1981, even the tool mill which had been modernized in 1964 went down, and the proud steel foundry, with all its record-setting achievements, followed a year later. Of the four blast furnaces which once lighted up Bethlehem’s skies, only one was operating in February. The mills did not revive even in this extended period of economic recovery. One can only assume they are down for good.

The whys of distress have been extensively chronicled. Foreign steel had captured as much as 25% of the American market, non-union, high technology mini-mills have skimmed off an estimated 25% more, and new substitute products reduced demand further as steel priced itself out of once-exclusive markets. Add to that steel’s high white collar and blue collar wage scales, persisting inflexibility on work rule changes, and some high level corporate misjudgments about the future and you see the dimensions of trouble. About 150,000 steelworker jobs vanished in the last three years alone, according to the American Iron and Steel Institute, and steelmaking capacity in the United States has dropped from about 150 million tons to 130 million tons a year. Both jobs and capacity are still dwindling in 1985.

Where will it end? Is this to be dismissed as part of the deindustrialization of America which some economists view as irreversible? Or is it a deterioration of our basic industrial fabric that can and must be stemmed for the sake of our national economic stability and security? If steel was once so important to our national interest that President Truman seized the mills and an angry President Kennedy personally intervened to halt a price increase, can it be much less crucial to our national interests today? And if big steel is still important, what will save it from this terminal pattern?

In this past year, I posed these questions to dozens of leaders of industry, labor, government, and independent institutions. While I found no consensus for national policy, I did find strong views on the future of the steel industry and some common threads on what ought to be done.

At the most adverse end of the spectrum, M. Colyer Crum, a Harvard Business School professor, views big steel’s demise as inevitable. Crum, an investment expert, makes it clear that he has no particular interest in the steel business. But he is interested in classic investment problems and, as he put it, steel happens to be a member of that group.

Back on May 10, 1979, at a time when the prevailing wisdom among steel economists was that signs of distress were temporary, Crum diagnosed them as terminal. In fact, he shocked many by declaring that Bethlehem Steel was on a course that killed the Penn Central Railroad and the steel industry’s “whistling past the cemetery” was an exercise of “painful future self-delusion.”

Crum’s speech, made at a meeting of the Young President’s Organization in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, was based on notes, but tape recorders whirred in the audience. Transcribed copies of his talk swiftly appeared in corporate suites back in the states.

Crum recalls that someone from Bethlehem Steel called even before he returned from Rio, leaving the message, “Would you give another speech and tell us the solutions?” With some chagrin, he replied, “You can’t change anything until you guys gradually get immersed in the message of what I tried to say in Rio. Which is, the decline is intractable, it’s long-term, and there is no quick fix. If you tell me you want another speech with solutions, you don’t understand the first speech.”

Crum’s projections were, of course, starkly on target. Has anything changed to moderate his grim outlook?

“The Penn Central went under because the pay was too high and the work rules too rigid, and a lot of its track went to the wrong places,” he replied. “That’s the way it is in steel. It is essentially the same. They are stuck with factories that are now in the wrong place, but they can’t change them…if you have a mill with no growth in America, it is going to be an old mill. If the wages are lower in Korea and you build a new mill, which is in the right place, then investors are not going to hold shares in Bethlehem Steel. That’s the simple message from an outsider who neither knows nor cares about details.”

The search for an expert who has studied the steel industry leads to the campus of Fordham University. This is the base of the Rev. William T. Hogan. This vigorous, modestly rotund priest is probably the most prolific writer and lecturer on the state of the industry. Not surprisingly, he viewed the future of big steel from a different end of the spectrum.

Father Hogan likes the way steel firms have been closing marginal facilities and cutting costs in surviving operations. He also sees a lifetime for the industry in President Reagan’s program to negotiate voluntary quotas that would restrict steel imports to 18.5% of the domestic market.

“Note that the tonnage that has been taken out–the 21 million capacity that has been lost since 1980–was mostly obsolete stuff,” Father Hogan points out. “Now that means what is left is more competitive than what the industry had five years ago…and every major company has under construction, or finishing construction, a continuous casting unit. That is going to make all of the industry more efficient.” Continuous casting eliminates several costly steps in steel-making.

“The aim now of some of the companies is to get man-hours down to four man-hours per ton of steel. The industry will have 60 to 85% of its tonnage continuous cast. (Japan attained a 90% average about five years ago.) That must be helpful. So you have a smaller industry operating better equipment, and I think there will be considerations other than wages that will be sought in future negotiations. Work rule changes? Whatever means that can be negotiated by is going to be the key to the solution.”

Father Hogan believes Reagan’s negotiated quota agreements with foreign countries are going to be a big help in coping with the shrinking market. “The import restrictions will give the industry about six or seven million more tons a year, providing this 18.5% limit is achieved and I think they will probably get close to it. The integrated mills should pick up a big chunk of it and another thing it will do is stabilize the price structure.”

By the time the five-year protection period expires, the industry can expect to see markets expanding again, according to the Hogan projections.

“Basically, this is where I feel there is no question. Some people feel the industry is dying–dying dinosaurs and so on. The industry is not going to die. There may be some change in the structure, but you’ve got something like 4 billion people plus now and by the year 2000 demographers seem to be sure there will be something like 6 billion people. And by the year 2020 you will have something like 8 billion people. And there never seems to be much luck about reversing this. The point is those people cannot live without an infrastructure. They can’t exist without it. And infrastructure is going to demand a fair amount of steel. So I think there is growth ahead for steel, but it is not next year or the year after, but by the 1990s you will see some change in this.”

In Charlotte, NC, F. Kenneth Iverson is uncomfortable with both views. As chairman of Nucor Corp., he is the chief executive officer of seven mini-mills that operate on four sites. Even in the depths of the recession, his company has returned a steady profit and no employees have been laid off, largely because his high-technology, non-union, profit-sharing mills invaded the traditional markets of integrated steel and even competed successfully against price-cutting imports.

Iverson insists the steel business must be viewed from a global perspective. He resents Big Steel’s penchant for looking to Washington for salvation. The import protection program forced on the Reagan administration will hurt the American steel markets in the long run, he said.

“Because quotas are designed to protect higher priced American steel, it will drive manufacturers out of the United States and force others to ‘source’ outside of the U.S.” That means those who make those big oil rigs, or autos or tractors will ship in parts and components from abroad to avoid manufacturing products with higher steel prices, thus circumventing the quota system which applies only to raw steel.

“If the market for American steel decreases because of that, the entire steel industry suffers and so does the U.S. economy,” he said. “Ironically, we will end up with a smaller steel market, making us shut down even further–which is the very thing quotas are designed to prevent.”

Iverson said integrated steel companies can help themselves best by working to reverse “bad decisions” made in the 50s and 60s. “Labor costs ran out of control. I’m not talking about dollars per hour…I’m talking about manning, not what they are paid. The main problem is the productivity and that’s related to them not being technically up to date and also to featherbedding–and here I include administrative and clerical people. The abuse there is just as bad as in the blue collar sector.”

Iverson said that with current technology mini-mills can produce only about 30% of the nation’s steel. That will go higher in time, he said, but this leaves integrated mills with a decent future if they improve on what they can do best–manufacture the big structurals, the larger pipes and the great amounts of flat rolled products needed for autos and appliances.

“But they have far too many people who are in their pocket,” he said. “I mean you got six guys on the furnace instead of three. That doubles your costs. You can cut your costs 10% but you really haven’t cut your costs that much because you are not producing. An illustration: the average integrated mill produces about 350 tons per employee. The average Japanese mill now produces about 800 tons per employee. To get from that 350 to 800 you have cut it in half. Well, you can’t do that. The most you can cut is 20% so that means that most of that has to come from better productivity.”

He believes American mills can match or exceed the Japanese performance, given the latter’s transportation disadvantage, and he points out that a big reason some of his plants do is because they are not burdened by work rules which the big companies granted during years of industry-wide bargaining. For example, in most mini-mills a crane operator will climb down from his machine and work as a laborer on the floor when there is no crane work to do. In the integrated mills, crane operators not only would likely file a grievance if asked to do so, but senior crane operators even have the contractual right to refuse to move from one crane to another during a work lull.

“You have to tell the union members that it is not in their best interests to lose their jobs,” Iverson said. “That shouldn’t be too difficult now after four straight years of losses. It’s in their best interest for the company to succeed. In order to get them to change old practice you have to do a little sharing along the way…of problems and profits.”

(Nucor’s success with profit-sharing for employees is a model in the industry. The concept has also been spreading in the unionized sector, notably among the automobile makers which are successfully using profit-sharing to win wage concessions.)

The big test on whether steel can break out of the old mold comes next year when the basic labor contract expires. The companies agreed to discard industry-wide negotiations which prevailed for 30 years. They each will now bargain independently and most firms are laying the groundwork for a major confrontation. Bethlehem Steel, for one, cut white collar workers by 40%. While the cuts were in the name of reducing costs, they defuse a standing union argument about administrative featherbedding whenever reductions in unionized, blue collar work crews are sought.

Robert Crandall, senior economist with the Brookings Institution and a leading industry watcher, feels it is crucial for the industry’s survival to end the old era of adversarial relationships. But he is not optimistic. He points out that mini-mills such as Nucor, which has no company planes, company yachts, or executive bathrooms, work hard at establishing trust and credibility with employees. Because integrated companies are handicapped by years of labor-management animosity, he feels only the brink of bankruptcy might persuade the union to change.

However, when Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel Corp., long one of the 10 top producers, was forced to file under Chapter 11 of the federal bankruptcy laws last April, the United Steelworkers union balked at the concessions to save the company because it said it had no confidence in the bank restructuring of the company debt.

“The companies have negotiated themselves into a position where it is going to be very difficult to negotiate themselves back out,” he said. Further, he is sharply critical of the caliber of big steel industry leadership and doubts that they can achieve productivity of even six man-hours per ton at the current pace of cost-cutting.

However, there have been some encouraging signs of labor and management working closer. The crisis in steel and the sharp drop in union membership generally caused considerable internal searching at high levels of the AFL-CIO. The executive counsel recently adopted a report, two years in making, which calls on unions to explore alternatives to the old “adversarial collective bargaining relationship.”

Even before the report was issued, the United Steelworkers made a significant switch in policy in that contract. The USW dropped opposition and cooperated in the sizable wage cuts and other concessions which were a condition for saving Weirton Steel in West Virginia. Reorganized into an employee-owned company, Weirton seems to be paying off the gamble. At a time most steel firms are reporting losses, Weirton turned in its fifth straight profitable quarter this spring-and steelworkers are working.

With strong community encouragement, an employee stock sharing agreement reached in April breathed new life into Bethlehem Steel’s failing Bar, Rod and Wire Division at Johnstown, Pa. The United Steelworkers there agreed to reductions in wages and benefits in exchange for shares of preference stock to be issued over the term of the 16-month renegotiated labor agreement. But none of this adds up to any real hope that a fresh wind will blow or that a new flexibility will prevail when labor and management sit down to tackle the new basic agreement next year.

Ed Ayoub, the respected economist on the staff of USW headquarters in Pittsburgh, says the top union leadership is well aware of the ills in the industry but denies labor costs are the root of the trouble. Their position is that foreign imports and the strong dollar are the chief villains and business can’t get better until those problems are licked.

Meanwhile, from Bethlehem’s local union hall to Branco’s Lounge in the shadows of the coke works, the mood is hardly upbeat. Ed O’Brien, president of Local 2598 who speaks for the three locals, grimly says “”things are worse than ever.” The union’s local presidents have the deciding vote on contract matters. Despite the recommendations of top leadership, O’Brien voted against concessions at the last contract reopening. There is no tone of conciliation in his voice again, and there is no sign that the rank-and-file is ready to tell him to do otherwise.

“The guys on top give themselves big pay raises and the offices are loaded with about 10 times as many vice presidents as they need and they want us in the plant to give concessions?” scowls Joe Dlugos, a steelworker on layoff and hoping his unemployment checks hold out until he qualifies for pension.

Robert Crandall, the Brookings economist who is critical of featherbedding on both sides, views it this way: “If your hope for your industry is to keep your wages 70% above the industrial average, and keep work rules where only 60% to 70% is productive, that’s a prescription for disappearing. If they wish to stick to that line, they are dead.”

©1985 John Strohmeyer

John Strohmeyer, editor and vice-president of the Bethlehem (Pa.) Globe-Times for 28 years, concludes his examination of a steel company’s battle to survive.