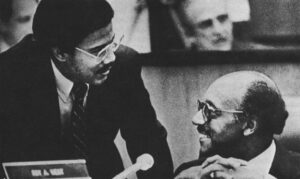

RICHMOND, Va.–On a cloudless late October day, Paul Goldman steered his cluttered compact through noontime traffic in the Confederate capital and contemplated the storm gathering on his personal horizon. Goldman, a transplanted New Yorker who had almost single-handedly managed Douglas Wilder’s historic campaign for lieutenant governor of Virginia, knew that victory astonishingly was within grasp. Seven days remained, however, and forces were massing that, in a week, might crush Wilder’s hopes of becoming the first black elected to statewide executive office in the South in the 20th Century.

The artillery for the anti-Wilder blitz would be a series of ads Goldman had just watched, grim-faced, in a Richmond television studio. Throughout the summer lull and into the quickening pace of the 1985 fall campaign, Wilder’s opponent–a congenial, if ineffectual state legislator–had avoided personal assaults. Now, however, John Chichester appeared on the brink of losing the unlosable race. Decorum had become an unaffordable luxury.

For weeks, Chichester had refused to exploit what his campaign manager and others insisted were “golden issues” against Wilder. The ads Goldman had just seen confirmed Chichester’s capitulation. “Despite being hauled before a grand jury convened to investigate him,” a stone-voiced announcer said ominously, “despite pleas of his neighbors for help, Doug Wilder maintains slums where other people are trying to raise families.” A camera spanned the renovated homes and picture-book flower beds of Richmond’s Church Hill, then settled on a facade with boarded up windows and an overgrown lot. “Douglas Wilder maintains these nests of urban blight,” the announcer intoned.

A second ad seemed equally devastating. Citing a 1973 Virginia Supreme Court reprimand for “unprofessional conduct” and “inexcusable procrastination” in a legal case, the ad concluded: “Today, a course of study still given all candidates for the Virginia State Bar cites Wilder’s conduct as an example of how not to practice law.” Yet a third ad provided the reminder: “He’s been publicly reprimanded by the state Supreme Court. He’s been hauled before the general court of Richmond for maintaining hazardous properties.”

Racing back to campaign headquarters, Goldman’s mind was abuzz with both fears and options. Should the ads (“The roughest I’ve ever seen,” he said) be countered or ignored? What were the dangers of becoming enmeshed in a mud-slinging contest? What were the risks of allowing such ads to appear unchecked? During the next 48 hours, a campaign that once had scarcely dared hope for victory was consumed with frantic debate over how best to preserve its fragile and miraculous lead. Pollsters, who saw Wilder’s margin slipping, advised a counterassault. So did Robert Squier, a Washington DC political consultant who had become an informal, behind-the-scenes advisor. So did a group of nine men–among them, a Wilder law partner, the campaign treasurer, and the clerk of the Virginia Senate–who gathered four nights before the election to view two hastily-filmed Wilder ads, one accusing Chichester of legislative conflict-of-interest. Those spots were distributed to television stations across the Commonwealth, ready for an 11th hour, weekend assault.

In the end, Wilder said, “No.” Television attacks would be left to the Republicans. His media finale would be, instead, an ad in which Gov. Charles S. Robb cited Wilder for “a clear edge in terms of experience, a clear edge in terms of effectiveness, a clear edge in terms of leadership.” By election night, the ten-point Wilder lead which had shown up in Democratic polls before Chichester’s ads began running had slipped to a 1.6 percentage point gap. But Wilder was still in front. For jubilant Democrats, any fraction of a percent was enough. In the sort of seminal event that forever changes political thought, Wilder had just proved that a black man could be elected to major office in a former Confederate state.

In the election aftermath, few argued that Wilder had removed race as a factor in Virginia politics. What he had done, most analysts agreed, was to skillfully avoid racial pitfalls. Among the decisions Republicans praised was Wilder’s refusal to mount a last-minute television counterattack. The reason, as with most analysis in this precedent-setting campaign, had racial overtones. “It would have played right into John’s hands,” said Edward DeBolt, a leading strategist in Virginia GOP campaigns for the last decade. “The first neat thing that Doug did was realizing he could never attack a white man and get away with it. As it was, he was a non-threatening, harmless black. It was the only strategy that would have worked, and he pulled it off beautifully.”

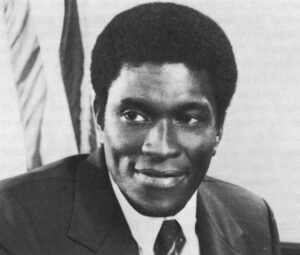

On election night, when Doug Wilder claimed victory in a crowded hotel ballroom where he had once waited tables, his words beamed hope into black homes and neighborhoods throughout the citadels of the Old South. Wilder, a suave yet street-wise Richmond lawyer, a 15-year Senate veteran, the grandson of a slave, had not only achieved what virtually every state political analyst had said was impossible. He had done so without a particularly heavy black turnout, and by capturing a stunning 4.6 percent of the white vote.

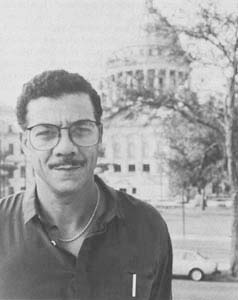

The election did not say that southern racism was dead. It did say unequivocally that skin tone is not the only, or even the predominant criterion on which many white southerners now base their votes. The results offered a measure of vindication to those southerners who have long insisted the once-scorned region would eventually set the national pace in race relations. It strengthened the resolve of black politicians like Jim Clyburn, who is planning a 1986 race for secretary of state in South Carolina, or Howard Lee, who hopes to seek the same office in North Carolina in 1988. And it provided a telling rebuttal to a chorus of Democrats, calling in the wake of the 1984 presidential elections debacle for a diminished–or, at least, less visible–role for blacks in the southern Democratic Party.

Since 1965, when the Voting Rights Act freed blacks for political entry, the number of black elected officials across the nation and the region has soared. In 1965, there were fewer than 100 blacks in elective office in the deep South states first covered by the voting act (Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia); by 1985, the number had grown to 2,351, 39 percent of the total nationwide.

Still, the vast majority of those officials served at the entry levels of government, in county and municipal jobs. Most, too, were elected from majority black districts. The ripest plums of political office remained outside the grasp of blacks. Whites still served black-majority congressional districts in Georgia, Mississippi and Louisiana, despite black opposition. Black candidates had led the initial balloting in races for North Carolina lieutenant governor in 1976 and South Carolina secretary of state in 1978; neither survived their primary runoffs. Three black men–one each in Georgia, Alabama and North Carolina–had won judicial posts in statewide elections. All three, however, were initially appointed by white governors and served on courts dominated by whites. Tokenism, it seemed, was acceptable to southern whites; electing a black officeholder to a statewide executive post was not.

Against that backdrop, Doug Wilder’s mid-1984 announcement that he was running for the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor of Virginia was greeted with emotions ranging from skepticism to dismay. Certainly, Wilder–a florid orator and scrappy fighter who represented the black side of Richmond in the Assembly–was no stranger to racial innuendo or to long odds. In 1969, Wilder became the first black elected to the Virginia Senate in modern times. Not long afterwards, Virginia’s moneyed establishment made clear its indignation over Wilder’s defeat of a prominent white conservative. He was the only senator who did not receive an engraved invitation to a traditional Assembly opening party hosted by a wealthy Charlottesville executive.

As late as 1983, the social stigma had not been fully erased. That year, Wilder had been giving Democratic Party officials fits by threatening an independent race for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Harry F. Byrd Jr. Alson Smith, the chairman of the House Democratic Caucus and a conservative fund-raiser for Chuck Robb, and two other prominent Democrats had been asked to take Wilder to lunch to try to sort out some of the problems. When Wilder suggested that they dine at the Commonwealth Club, a downtown Richmond bastion of white male conservatism, Smith–a member–refused. “Life’s too short for me to be embarrassed by taking you to the Commonwealth Club,” Wilder recalls Smith saying, as his colleagues listened in strained silence. “They don’t like blacks there.”

Throughout the fall and winter of 1984, opposition to Wilder’s candidacy for lieutenant governor festered within Democratic circles. A prominent University of Virginia political scientist gave Wilder “100 to 1” odds of winning the general election, and–based on 1984 presidential election trends in the South–suggested that he might even pull down Democratic running mates for governor and attorney general. Robb’s press secretary, asked about Wilder’s prospects, publicly lamented: “”This is still Virginia.” Wilder was slipped private assurances that the state party chairmanship would be his if he would only step aside. And in a final blow, eleven prominent legislators, including the state Democratic Party chairman and the speaker of the House, were caught in a secret meeting aimed at discussing their fears of the “Wilder problem.”

Even Wilder, who maintained a perpetual optimism throughout the campaign, seemed taken aback. “I didn’t know how difficult it would be until I announced,” said Wilder, on a wintry day in January 1985. As he gazed through a frosted legislative office window, overlooking the capitol square statues of George Washington and Harry Byrd Sr., Wilder mused: “I never would have expected a secret meeting. I never would have expected the comment from the governor’s press secretary. I thought the governor would have been more embrasive…Fortunately, the acceptability with the people is far more open. There aren’t any places that I go that people–white people–don’t say, ‘I’m supporting your candidacy.’ “

Within a month, a more prominent white Virginian had come calling on Wilder. Atty. Gen. Gerald Baliles, then a decided underdog in the contest for the Democratic nomination for governor, quietly began driving to Wilder’s stately home in an integrated neighborhood for a series of evening chats. Baliles, who would eventually score an upset victory, badly needed a slice of the black vote in his nomination battle against a more liberal opponent. Wilder, in turn, could use increased credibility among conservatives and help in staving off a right-wing party challenge. An alliance was formed.

What virtually cemented Wilder’s hold on the lieutenant governor’s nomination, however, was a gutsy power play during the spring of 1982. That year, Democrats stood ready to nominate a moderate suburban legislator from Virginia Beach for the U.S. Senate. Blacks, meanwhile, had been angered and embarrassed by the indifference of the white Democratic power structure in the 1982 legislative session. When the prospective Senate nominee appealed to conservative backers of former U.S. Sen. Harry F. Byrd in his opening campaign speech, blacks led by Wilder decided to show their clout. Wilder threatened an independent candidacy. The Virginia Beach legislator, who had enough committed votes to win the Senate nomination, was finally forced to withdraw at the urging of Gov. Robb. Seldom, if ever, had a southern black politician so successfully manipulated political power.

Shoestring Campaign

By 1985, the lesson had not been forgotten. White Democrats grumbled about Wilder’s bid for lieutenant governor, but none was willing to tackle him head on. The party in 1982 had already come to grips with the futility of waging a statewide campaign without black support. If Wilder and other blacks went away from the 1985 nominating convention miffed, the party’s prospects in the fall elections were worth less than a handful of used paper ballots.

Post-nomination, Wilder’s campaign was a shoestring classic, fueled by the candidate’s personal blend of sophistication and backroom savvy. A millionaire lawyer and real estate entrepreneur, Wilder locked his white Mercedes in the garage and set off on a statewide tour in a borrowed station wagon. Along the way, he and a small group of white Senate advisors pushed the right pressure points whenever Democratic support seemed lukewarm. For instance, House Speaker A. L. Philpott (who had stopped calling blacks “boys” after a public chiding from Wilder, but still on occasion referred to them as “n…..s” in private) was reminded of the tactical advantage if ten black members of the House suddenly owed him an immense debt of gratitude. Philpott, who had been plagued by rumors of an impending coup in the legislature, decided to host a breakfast for Wilder. He was the first old-school white Democrat to take the plunge, and the breakfast was viewed as a turning point. Ever after, Democratic officeholders were reminded that they could do no less than A. L. Philpott.

Meanwhile Wilder and Goldman–a former Vista worker with a quirky and largely unproved political brilliance–adopted an unlikely campaign strategy. Shredding candidate workshop manuals, they decided to limit their paid staff to two, plus a driver, and to pour their resources into television. In the end, about $500,000 of a $700,000 budget was spent on media advertising. The ads stressed Wilder’s selling points: that he had more Senate experience than the last five lieutenant governors combined, that he had chaired three major Senate committees, that he had placed fifth in Senate effectiveness in a recent newspaper poll, that he had won a bronze star in Korea, and that he was the author of legislation controlling drug paraphernalia and setting tough penalties for prison escapees. The list contrasted with the lackluster record of his opponent, John Chichester. Chichester’s major claim to fame was having defeated the Equal Rights Amendment in the Virginia Senate a few years earlier.

The masterpiece of Wilder’s advertising campaign, however, featured a burly, white cop from Kenbridge, VA, who happened onto a filming session one day and readily lent his support. When Joe Alder rested one beefy arm on the top of his patrol car and witnessed to his support of Wilder for “loo-tin-yant guv-ner,” he delivered a body blow to one of the most damaging of racial political stereotypes. Boss Hogg and Archie Bunker might just as well have sent their blessing. Redneck Virginia liked Wilder. Joe Alder and the tagline–”They stand together in the fight against crime”–had put to rest any notion that Wilder might be soft on criminals.

Throughout the campaign, Wilder downplayed race as an issue, even as he benefited from press fascination with his seemingly quixotic mission. In August, a Charlottesville newspaper survey found, the Washington Post ran six pictures of Wilder and one of Chichester. The Richmond Times Dispatch that month devoted 100 column inches to stories in which Wilder figured in the lead paragraph. Chichester, whose strategists remained confident of victory, commanded no such stories. Wilder, meanwhile, insisted that the media and political consultants cared more than voters about racial matters, and unlike previous black candidates across the South, he rejected advice that he keep his face off television and out of the newspapers.

Mindful of the political backlash, more than one southern black politician had previously tried to avoid broadcasting his race. Frequently, as Wilder recognized, the effort was fruitless. A white opponent made sure the public understood who was in the running. In one of the less subtle messages, Webb Franklin–who today represents Mississippi’s majority-black 2nd congressional district–in 1982 ran commercials against Robert Clark, the black Democratic nominee, asking simply: “Do you know who my opponent is?” In 1982, when Judge Oscar Adams, a black Birmingham trial lawyer who had been appointed to the Alabama Supreme Court, stood for his first election, he kept his picture off billboards and literature. A television spot showed a bench and gavel, not Adams. His opponent in the Democratic primary runoff responded by including pictures of Adams in his television ads. Adams, who had the backing of the Alabama trial lawyers association, the governor, the state AFL-CIO, the teachers association and various other groups, still won. But his 75,000 vote lead in the first primary was whittled to 17,000 votes in the runoff.

If Wilder did not hide his race, he also did not accentuate it. He avoided racial stereotyping, and consciously moderated his image and tone. He rejected offers from Jesse Jackson and other prominent blacks to come to the state to campaign. He deftly explained away past votes on opposition to capital punishment and supporting public employee negotiations, confounding Chichester’s attempts to paint him as a dangerous liberal. And Wilder-who once publicly exploded over racial connotations in the state song, “Carry Me Back to 0l’ Virginny”–even began telling jokes about CPT (“colored people’s time”) and WPT (“white people’s time”). Asked about campaign lessons for blacks nationally, Wilder in a post-election analysis cited first and foremost the virtues of running as a political moderate. Key also to Wilder’s victory were the demonstrable gap between his qualifications and Chichester’s, and the remarkably divided and lackluster Republican campaign.

Spectacular as Wilder’s victory was, however, southern political leaders view it primarily as a milestone, not as the climax of an evolutionary shift. It will, they say, take more than one triumph to spell the end of race as a factor in regional politics. Nationally, as well, black progress cannot be charted in a steady upward line. As 1986 began, blacks held four statewide executive positions, lieutenant governor of Virginia, treasurer of Connecticut, comptroller of Illinois and secretary of state in Michigan. Eight years earlier, in 1978, however, the list of statewide black officeholders was twice as long. It included lieutenant governors in California and Colorado, secretary of state of Michigan, treasurer in Connecticut, U.S. senator in Massachusetts, superintendent of education in California, and comptroller in Illinois.

Certainly, black politicians throughout the South found cause for hope in Wilder’s victory. Still, their assessments were cautious. “It’s going to make it much easier for black candidates to decide to run, and for major parties to feel comfortable with their running,” said Linda Williams, senior analyst at the Joint Center for Political Studies, a black-oriented think tank in Washington, DC. “But I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s the start of a trend.”

White politicians agreed. Don Fowler, national Democratic committeeman and a former state party chairman in South Carolina, noted: “The Virginia mix and circumstances were peculiar. Just because it happened in Virginia in 1985 doesn’t mean it can happen in Alabama in 1986 or Georgia in 1987.”

In Alabama, Birmingham Mayor Richard Arrington, who is black, described the idea of a 1986 Senate race against Republican Jeremiah Denton as “appealing…except that I know it’s doomed to failure.” In Mississippi, Democratic Chairman Steve Patterson, a Jackson investment banker, acknowledged that a black candidate “probably could not” win statewide in the 1987 elections. And in Georgia, Kenny Johnson, acting director of the Southern Regional Council, said the overwhelming evidence from past presidential, congressional and local elections argues that a black candidate would fare poorly in a statewide contest there. “In fact, we’re a long, long way from that,” he said.

Just as Doug Wilder’s experience is emblazoned on the 1985 southern political fabric, such leaders realize, so are events like those in Dallas County, Ala., last spring. Dallas County is a pastoral expanse of farm and timberland, separated from Selma by the Alabama River. It was at the foot of the Edmund Pettus bridge, which spans those swirling waters, that Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark in 1965 led the bloody charge which halted civil rights marchers and produced the Voting Rights Act.

The county’s population is 55 per cent black, but in 1985 as in 1965, no black person had held a county office since Reconstruction. That was to have changed in 1985. Jackie Walker, a young black woman, had been elected tax collector the previous fall. Her election climaxed a community-wide push by black leaders. But Walker was killed in an automobile crash on an icy highway before she could take office.

At first, blacks felt hopeful that the all-white county commission would appoint Walker’s husband, or some other black person, to the job. Filling a vacancy with the spouse of a dead official is traditional in rural Alabama, blacks argued. And besides, they added, Walker’s election had been a victory for all Dallas County blacks, a breakthrough which should not be so capriciously erased. A major campaign was mounted. In the end, blacks mustered one vote for their cause. The all-white commission voted 4-1 to name Tommy Powell, the white man whom Walker defeated, to the post.

Nor can southern political leaders forget the list of failed black candidates who preceded Wilder. In Mississippi, there were Charles Evers’ bids for governor–and senator, Charles J. D. Tillman’s run for commissioner of agriculture and commerce in 1983, and Robert Clark’s 1982 and ’84 races for Congress from the Delta. In South Carolina, politicians remember Jim Clyburn’s 1978 loss for secretary of state and Cecil Williams’ 1,200-vote defeat in the 1984 U.S. Senate primary. In Louisiana, there was Judge Israel Augustine’s unsuccessful 1984 bid to unseat Rep. Lindy Boggs in a majority-black district and Ben Jeffers under-funded race for secretary of state in 1979. Across Alabama, Georgia and North Carolina, the names are different, the results the same.

If that roster is discouraging, however, the scene at Richmond’s John Marshall hotel on election night 1985 should warm the hearts of blacks nationwide. In a glass-and-gilt ballroom packed with Democratic revelers, Wilder was clearly the politician of the hour, easily upstaging his white ticket-mates. The winners for governor and attorney general had long since left for their private celebrations But still, the throng of men and women, white and black, young and old, pressed forward for a touch of Wilder’s hand.

“Hey, Doug. Hey, Doug,” they shouted, as sweat streamed down Wilder’s glowing face.

“I brought you Hampton. I want you to know,” called out a white legislator.

“God bless you; we prayed for you,” an elderly black woman said softly, clutching Wilder’s palm.

A child was lifted above the crowd for a kiss. A woman hugged Wilder and then, speechless, erupted in laughter. Signs, brochures, newspapers, even a T-shirt, were thrust upward for autographs. A white businessman stood watching the scene in awe. “It is,” he said, “part of the magic and miracle of America.”

In that room, for that moment, southerners black: and white had overcome.

©1986 Margaret Edds

Margaret Edds, reporter on leave from the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot/ Ledger Star, concludes her report on Black political power in the South.