By ‘jiving’ and ‘schucking,’…a man may avoid the undesirable consequences of his own misdemeanors…’

– Ulf Hannerz, Soulside 1

(NEW YORK) – In this passage Professor Hannerz is describing one of the central elements of black life style analyzed during his sociological study of a relatively contemporary inner-city community. The behavioral pattern described, however, besides its import as a means of survival within black communities and as a buffer against hostility encountered in interactions with whites, is also one of the essential characteristics of traditional black American humor. Moreover, despite its continued evidence in black communities, its roots extend nearly as far back as the initial presence of black slaves in North America.

Soon after their arrival in the colonies, after a basic pidgin English had been mastered, black slaves adopted a form of inner-community communication in which the element of obliqueness, double entendre and metaphorical discourse were prominent characteristics. These verbal traits were, of course, initially rudimentary, and in part a carry-over of discourse characteristics common to the West African societies from which most of the slaves had come. But the style of communication was most probably so readily embraced because while it effectively permitted slaves to satisfy their owners’ demand that they demonstrate a nonthreatening posture, it also allowed them to function without feeling total psychological capitulation to the lowly state of bondage. Furthermore, it permitted them a kind of surreptitious defiance even in the presence of whites and, when employed exclusively among themselves, provided outlets for forthright contumacy as well as some much needed levity to counterbalance the hardships of their condition. A familiar slave story about Pompey illustrates both the tenuous balance of acceptable defiance that was permitted and the incipient form of black humor that emerged from plantations in the ante-bellum South:

“I gits long tolable well wid my massa, said Pompey.

“How cum you gits long tolable well wid yo massa? “demanded Jim. “He meaner ‘n

my massa! “

“I jes cuss im out real good when I’s a mind ter,” said Pompey.

Jim was astonished. “An’ nothin happen ter you?”

“Nothin a’tall. Try it yosef – it sho make you feel good. “

Jim agreed, but when he met Pompey the following afternoon his face was badly bruised and his back a mass of ugly welts from the rawhiding he had received. “I done like you say an really cuss im out,” Jim moaned, “but massa, he toh me up.”

“Whar you wuz when you cuss im out?”

“Why, I was stannin right befo his face, dats whar. “

“You oughtta have mo sense dan dat,” Pompey said.

“Now when I cuss my massa I wait til he up at de big house an I stannin down at de othuh en of de field.”

This Pompey story is a representative example of the thousands of tales collected by folklorists over the years and, on the surface, demonstrates most of the characteristics that Professor Hannerz attributes to the stylized verbal facility of inner city blacks as recently as the mid-1960’s. The connecting thread is guile veiled by an innocent, foolish or obsequious posture and a distinct bent toward misdirection and exaggeration as a further manipulative ploy. As an examination of ante-bellum folktales illustrates, the veneer of obsequiousness demonstrated by blacks in specific circumstances varied more or less along lines determined by whether whites were present or absent. The input of irony and veiled protest in field or slave quarter tales contrast markedly to tales about house slaves who were continually interacting with whites. But the style itself – the complex ploy of masking genuine feeling with mirth and indirection – seems to have become a characteristic aspect of the black life style. Illustrations of its perpetuity can be found in novels, essays and memoirs throughout Emancipation, Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era and, as shown by Professor Hannerz and other social scientists, as recently as the 1960’s.

And while that style was molded and nurtured to a certain extent by bondage, it also supplied the framework for black America’s distinct brand of humor. “It was from these very depths of agony,” writes Henry D. Spalding, editor of Encyclopedia of Black Folklore and Humor, “that the slave’s wit and humor emitted its first faint sparks – sparks struck from the flint-stone of grinding hardship; fanned to glowing embers by the dawning realization that these humorous allegories were a comparatively safe means of protest and intra-communication. “

The minstrel shows of the early 1800’s – white theatrical interpretations of black humor – provided the first publicized impression of the black comic style. But the interpretation was, as one might expect, superficial and pointedly hollow.

Animal tales and verses, which blacks had used to express protest over their condition, typically became simply nonsense rhymes: “Dare was a frog jumped out de spring,/It was so cold he couldn’t sing,’He tied his tail to a hickory stump,/He rared and pitched but he couldn’t make a jump.” Authentic double-edged satire was reduced to meaningless puns: “Gentlemen be seated,” Mr. Bones would say. “Why is a journey round de worId like a cat’s tail?” “Coz it’s fur to the end of it,” Mr. Tambo would reply.

And, not unexpectedly, since minstrel shows were performed before white audiences who came to be entertained, not assailed by moral or social issues, minstrel performers portrayed blacks who reflected little of the irony of what, by the mid-1800’s, had become an entrenched black survival technique. While some folk and anti-slavery material had been included in the earliest shows, after the mid-1850’s, according to Robert C. Toll, author of Blacking Up, minstrels “thrust aside wily black tricksters and antislavery protesters for loyal, grinning darkies who loved their white folks and were contented and indeed fulfilled by working all day and singing and dancing all night.”

Even the black performers who entered minstrelsy in the late 1800’s had little effect in altering the simplified and grossly distorted image of blacks created by minstrel shows. Entertainers such as Billy Kersands attempted to add some authentic vestiges of the irony of black folk humor to their performances but, generally, they stuck with the caricatures and nonsense gags that audiences had come to expect. (Kersands, for instance, was noted for his ample lips and mouth and, during his act, would dance with three billiard balls tucked inside his cheeks. He often quipped, “If my mouth was any larger, they’d have to move my ears.”) By this time the stereotypes established by the early minstrels had become America’s image of blacks. White audiences insisted upon seeing them acted out. And, perhaps more disturbing, influenced by the caricatures of their white “delineators,” many blacks seem to have lost sight of the original complexity and veiled humanity that both enlivened the survival ploy of “playing the fool” and gave substance to the humor derived from it.

By the beginning of the 1900’s, the black image had been codified; considered frivolous, unambitious and dimwitted, blacks were not to be taken seriously. A well known Eastern literary figure would later sum up the public estimate with the remark: “Negroes are either grinning or they’re dangerous.” Black entertainers, performing in the style that had been developed during slavery, but eliminating the satiric wit that had initially accompanied it, generally reinforced the negative image.

The external form of the black life style and of black humor had been co-opted – exaggerated and rendered palatable for a white audience; the glibness and patterned indirection of speech, the feigned obsequiousness and practiced mask of frivolity, which downtrodden slaves had adopted to exact some small edge in dealing with slave masters, had undergone a complete turn-about. It was now used to ridicule black freedmen and assure that they stayed in their place.

Even so, minstrelsy and the emerging tent shows and vaudeville acts were extremely popular – even among blacks. For black audiences who watched the shows in segregated auditoriums, performers like Kersands, Ernest Hogan and, later, Bert Williams, must have provided a humorous view of characters and types who were recognizable and familiar. Also, after laughing at exaggerated stage caricatures, the servile postures required in the Jim Crow world in which blacks actually lived and worked probably seemed less demeaning.

Still, many blacks criticized these shows for fostering and reaffirming denigrating portraits of black life that had been established by whites. Bert Williams responded by pointing out how much black audiences enjoyed the shows; he also voiced the black entertainer’s dilemma over white audiences’ demand to see the familiar “coon” acts and some blacks’ insistence that all demeaning material be excluded. Williams justified his own stage performances by claiming that he created his stage characters in the image of “the mass and not the few.” Although he, and other black vaudevillians, continued to perform without much interference from the newly emerging black elite who initially sounded the criticism, the groundwork for black censoring of images projected by the media had been established. Later, the criticism would be more insistent and effective.

Meanwhile, with Bert Williams as mentor, a host of bright young comedians emerged in the 1920’s and 30’s – among them were Pigmeat Markham, Dusty Fletcher, Lincoln Perry, Butterbeans and Susie, Tim Moore, Moms Mabley, Bill Robinson, John Mason, Mantan Moreland and Flournoy Miller. If there was a golden era of authentic black humor in the public forum, it occurred at this time. These comics, performing primarily on the circuit set up by the Theater Owners’ Booking Association in black theater across the country, gradually began breaking away from the restrictions on black comic interpretation established by minstrelsy and early vaudeville. They still worked in blackface, but now they seldom performed before whites and, once again, the humor began to assume some of the satirical thrust and double-edged meaning of the original slave quarter humor.

Many of the classic routines of the black comedy tradition were developed during this period. Pigmeat Markham originated the “Here come dc Judge” bit that later resurfaced on the “Laugh In” TV show with Sammy Davis, Jr. as the judge. Dusty Fletcher introduced his famous “Open the Door Richard” routine, in which he entered the stage bellowing, “Here I is, drunk again,” then proceeded to climb nearly to the top of an unsupported ladder and sway precariously above the audience as he pretended to call to an unresponsive friend who would not let him enter his house. And there were countless other routines, really too many to mention.

The proof of the quality of the black comedy of this era, perhaps, is best reflected by its numerous imitators. “A lot of bootlegging was going on,” wrote the late Godfrey Cambridge in a Tuesday Magazine article. “White performers took the rudiments of Bert Williams’ act and stylized them into successful formulas. This was the case with another Negro act called Butterbeans and Susie. Butterbeans originated the routine about the guy with the dumb wife who is always being bugged by her, and this later got translated as George Burns and Gracie Allen.” Many other black old timers contend that the list of comedy routines borrowed from performers on the TOBA circuit could be expanded indefinitely; the point is that during this time black entertainers were creating comedy routines that, usually in the hands of others, would become American comedy classics. As for adopting other performers’ routines, since comedy bits are not easily copyrighted, it is not an unusual practice. Years later, for instance, at the Blue Angel in New York City, Nipsey Russell, Slappy White, and Timmie Rogers reportedly showed up at a Dick Gregory performance with a tape recorder openly displayed on their table. They watched the show with apparent contempt, then left. Later, Slappy White wrote Gregory, a letter saying, “We wanted to find which of our material not to use anymore.”

But, just as the comedy of the TOBA circuit began to flourish and display some of the complexity and satire of traditional inner-community humor, another obstacle was encountered. Lincoln Perry, who as a vaudeville dancer-comedian worked with Ed Lee in a team called Step and Fetchit, moved to Hollywood. In his stage act Perry had combined a slow-moving, doltish demeanor with nimble dance steps to produce a comedic presence that usually captivated his audience. It had tension and reflected the satire and misdirection that is the core of traditional black humor. The implication was, “You may think I’m dumb and lazy, but I can be as subtle and nimble as I choose to be.” The impact must have been similar to that created by an act that appeared later on, in which a 300 pounder dragged himself center stage then proceeded to perform a dance routine worthy of a svelte Bill Robinson. In films, however, Perry performances were reduced to one dimension; the character he portrayed was simply an illiterate, lazy black whose chief pursuit was avoiding work. The comic image of Stepin Fetchit and subsequent performers who played similar roles became widely known, while the comedy of TOBA performers like Pigmeat Markham, Dusty Fletcher and Butterbeans and Susie remained anonymous to most, except in pirated form.

By the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, however, the mood of the black audience had changed. Protests about the image of blacks projected by the media, which had begun much earlier in the century, became more insistent. With the clamor, the “dumb coon” image soon disappeared from the comedy scene, and shows like “Beulah” and “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” which had been broadcasted on radio for 26 years and had begun a successful run on television, were forced off the air. At about the same time a fresh group of tuxedo-clad, standup comedians began to be heard from. Among them were Nipsey Russell, Allan Drew, Timmie Rogers, Slappy White and Redd Foxx. The face of public black humor was changing drastically. No longer did black comedians limit themselves to bouncing their satire off a toothsome smile or a diverting shuffle; conversely, it was no longer necessary to punctuate accommodating remarks with those incredulous facial expressions that Robert Guillaume would later aptly describe as “mumbling on the face.” The barbs could now be direct, and they most often were: “We were so poor,” Redd Foxx would say, “that once a week, I think it was Wednesdays, my grandfather would holler upstairs to grandma to tell her that the garbageman had come. And grandma would yell down to grandpa, ‘Well, tell him to leave three cans.”‘

The time was simply not right, however, and although these comics were successful in black clubs they rarely attracted integrated audiences or played white clubs. Still, the comedians of this era did reflect the growing mood of militancy among America’s black population. Ironically though, even as the content of humor moved closer to the aggressive thrust of inner-community black humor, the style with which it was delivered diverged sharply from that of traditional black comedy. Foxx and most of his contemporaries told jokes; as standup comics they worked in much the same vein as borscht belt comics like Milton Berle and Henny Youngman. Generally missing from their routines were the complex intricacies, double meanings, and indirect subtlety of traditional black humor.

Mass public acceptance of the new breed black comedians would not come until the 1960’s and the heat of the civil rights movement. Dick Gregory was the first to achieve prominence. With the nation’s eyes glued to the brutality of Southern resistance to the black push for equality, his timing was perfect, and he pulled no punches: “What a country! Where else could I have to ride in the back of the bus, live in the worst neighborhoods, go to the worst schools, eat in the worst restaurants – and average $5,000 a week just talking about it.” The success of Gregory’s pointed social commentary opened the doors for a raft of new black comics such as Flip Wilson, Bill Cosby and Godfrey Cambridge as well as older performers such as Redd Foxx and Moms Mabley. Moreover, for the first time, through Gregory’s humor the gap between public humor and that of the black inner-community was almost totally eradicated. The traditional style, however, had been lost in the transition.

The complete resurgence of traditional black folk humor was to be prompted by two younger comics: Flip Wilson initially, then, Richard Pryor.

From the offset, Wilson approached humor as a storyteller rather than as a one-liner comedian. He created characters, put them in an imaginary black world and wrung laughs from the absurity of twists and turns that his tales inevitably took. There were rarely punch lines, instead Wilson ended his tales with clever aphorisms that either clarified or amplified the events that preceded them. An example is the story of “Herman’s Berry,” in which Roman Herman finds a priceless berry and, after some convoluted plot twists, gives it to his wife. The story ends when soldiers come to Herman’s door. “You come to praise her berry,” Herman says. “No,” the soldiers reply, “we come to seize her berry not to praise it.”

Wilson’s style – the tall tale format, the indirection and peripheral detail, even his boyish smile and feigned innocence – is almost identical to the early style of black folk humor. It is also basically the same as the style of “rapping” that Ulf Hannerz describes in his comments on shucking and jiving in ghetto neighborhoods. With Flip Wilson, however, the acerbic thrust is missing from the humor. He is about having fun and, except for early tales about characters like Jive Junky Leroy, his humor usually diverges sharply in content from typical inner-community humor.

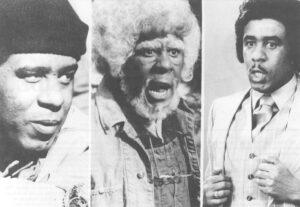

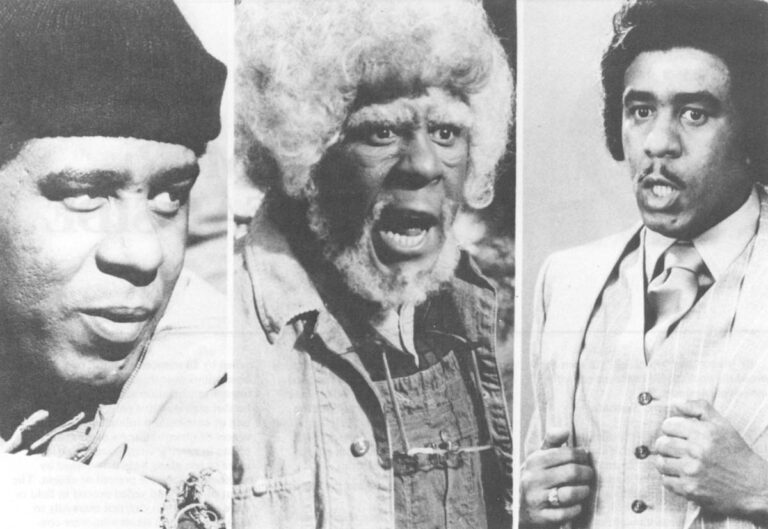

Richard Pryor, like Flip Wilson, is also a storyteller. At the start of his career his comedy act was very similar to Bill Cosby’s; he often told stories that were reminiscent of Cosby’s Fat Albert tales. But in the early 1970’s the content and subject matter of Pryor’s humor was drastically altered. Instead of mildly humorous reminiscences of adolescent pranks and conflicts, his stories began to reflect the tone – with the disappointments, rancor and blunt self-assessments – of the black masses. Increasingly, racial conflicts, the conflict between the sexes, police brutality, drugs, pimps and prostitutes – even death – were the subjects that dominated his material. A typical opening to his live performances demonstrates his approach: “Good God! Boy, a lotta “n…..”s here today, and some white folks too … come in a bunch didn’t yall – [in an exaggerated Midwestern accent] ‘stick with me, don’t worry about a thing.”‘

In Rolling Stone magazine Pryor’s style was described as a “new type of realistic theater” that presented “the blemished, the pretentious, the lame – the common affairs and crutches of common people.” And, indeed, Pryor’s humor usually is focused on human foibles, whether the object of his dialogues are black or white he goes for the gut. Aptly, he often punctuates his more serious stories with the introduction, “on the real side.” And, like most traditional black humor of the past, Pryor’s humor is an inseparable combination of pathos and mirth. (In a long tale about his experiences with the law and the courts, he quips, “They give “n…..”s time like it’s lunch down there. You go down there looking for justice, and that’s what you find – just us.”)

In much the same manner as Flip Wilson, a key factor in Richard Pryor’s humor is his ability to invest nonblack situations with a black perspective that is both revealing and funny. An example is his routine about a wino meeting Dracula: “Hey man! Say “n…..” – you wid the cape! What you doin peepin in them people’s window? What’s your name boy? Dracula? What kind of name is that for a “n…..”. Where you from fool? Transylvania! I know where it is “n…..” – you ain’t the smartest motherfucker in the world, you know. Even though you is the ugliest. Oh yeah, you ugly! Why don’t you get your teeth fixed “n…..”? That shit hanging all out your mouth – why don’t you get yourself a orthodontist? That’s a dentist, you know … ha, ha, ha.” The humor is derived from the absurd clash between two cultural viewpoints. But, in addition, since the character of the wino incorporates so many common assumptions held by blacks (casting him as a wino allows Pryor to exaggerate his response), the dialogue also provides an incisive view of black attitudes that are seldom displayed before whites.

Finally, though, what is most important about Richard Pryor’s humor is that he has revitalized, on the public level, a black folk tradition that was very nearly submersed by watered-down attempts to make it more palatable. Pryor’s appeal to both white and black audiences should make it clear that the attempt was folly.

End Notes:

1.) Columbia University Press, New York, 1969.

©1979 Mel Watkins

Mel Watkins ends his fellowship study on Black Humor from Stepin Fetchit to Richard Pryor with this issue.