(NEW YORK CITY) – “When I came to New York in 1931,” recalls Honi Coles, “Harlem was completely different. You can’t visualize it. You can’t possibly visualize it. In the first place, there was little crime, I mean street crime. There was no thought of mugging… none of that existed. Seventh Avenue probably was the prettiest street in all of New York City. It was tree-lined on both sides, from 110th Street to 155th. The island in the middle was wider, and people utilized it – sitting out all hours of the night. Something was always going on. You could go up Seventh Avenue any time of night, especially above 125th Street, between 125th and 145th I’d say, and there must have been a thousand little after-hours spots, you know, and always with some entertainment.

“You’d see all these chauffeured limousines out there, chauffeurs sitting up sleeping; they were for, say, people who’d been to Connie’s Inn or the Cotton Club, downtown people. This would be at eight o’clock in the morning; kids would be going to school, and the chauffeurs would be waiting for these people to come out of the joints, like Dickie Wells or whatever. Rich, rich people- celebrities, politicians, royalty, like the Duke of Windsor. Harlem was his hangout; he made all of the joints. Dickie Wells’ spot was the most famous, and Dickie was probably the most popular man in Harlem. There was wonderful entertainment, stars from the big clubs like Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Ethel Waters and Duke Ellington, and lesser known people like Josephine Garrison, whom Martha Raye copied note for note and breath for breath, or the Tramp Band who played Duke Ellington’s arrangements on washboards and kazoos. People would sit up in those spots ’til ten or eleven o’clock in the day… One of the things we used to do as entertainers was, we’d make every bar, even if we just looked in. We’d go from Small’s, to The Yeah Man, to Jock’s and come on down to the Braddock Bar, where all the chorus girls from the Apollo or the Harlem Opera House hung out-naturally you had to stop there. Sometimes there were problems, of course, with the mob and such, but it was a treat, Harlem was a treat. It was the entertainment mecca.”

The Old Masters

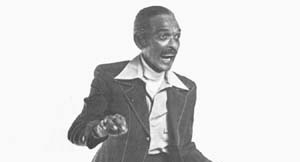

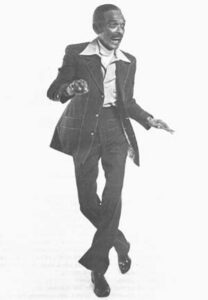

Honi Coles is among that dwindling group of venerable black performers (among them are Avon Long, Eubie Blake, Butterfly McQueen and, of course, Stepin Fetchit) whose personal experiences and recollections of show business history offer a richly detailed index of the gradual evolution of black entertainment. Having actively worked as a dancer and, on occasion, as a comedian for nearly a half century, his observations of the changing styles of black entertainment and humor and of the performers who accomplished those changes are crucial to a realistic assessment of black comedy from 1930 to the present. His viewpoint is particularly illuminating since-having worked closely with comedians from Dusty Fletcher and Tim Moore to Timmie Rogers and Redd Foxx, yet not primarily a comedian himself-his comments on the subject are less inhibited by professional considerations. In 1931, at age 20, Honi Coles left Philadelphia and came to New York City. He arrived with a dance act called The Miller Brothers, which included George and Danny Miller, and his first job was at the old Lafayette Theater. “We worked on pedestals about six-feet high,” he recalls. “We were probably one of the most sensational dance acts that had hit New York at that time. But we were totally dumb, I mean as far as calling downtown to the Broadway people or having agents. After the Lafayette, I think we worked a couple of small dates in Brooklyn, and then went into a show called ‘Humming Sam.’ which opened and closed after one performance. Consequently, being so naive, we were effectively stuck in New York, no money, no job.”

Fastest Feet in the Business

For the next year or so, after he had returned to Philadelphia, Honi Coles practically closeted himself in his apartment practicing. “When I returned to New York, around 1934,” he says, “I had the fastest feet in the business-bar nobody.” He worked as a single for a short time, joining comedian Pop Forester, Billie Holiday, and others in an act that worked the small clubs in Harlem. “At that time, I couldn’t stand Billie’s singing,” he says. Later, he joined the Lucky Seven Trio, which became known as the Three Giants of Rhythm. This group worked the downtown Cotton Club in New York and theaters like the Howard in Washington, D.C. or the Regal in Chicago, with big bands such as Duke Ellington’s and Louis Armstrong’s. After leaving the Giants, he joined Bert Howell in a comedy duo, and also did a single dance routine and toured with the Cab Calloway Band.

His career was interrupted when he was called into the army in 1946 but, shortly after returning, he joined Charlie Atkins (a former member of the Cotton Club Boys) to form the team of Coles and Atkins. They played Las Vegas with Tony Martin (whom Honi had met in the service) and later with Pearl Bailey, appeared in the Broadway hit “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” with Carol Charming, and did shows such as “Kiss Me Kate” and “Girl Crazy” in summer stock. Coles and Atkins, like most tap dancers, found work scarce in the late 1950’s and, although they occasionally worked in shows with Billy Eckstine, Honi Coles took a job as manager of Harlem’s Apollo Theater in 1960. He stayed at the Apollo until 1976. In the last three years his dancing career has been on the ascent. He has done several television projects, appeared in the Broadway version of “Bubbling Brown Sugar” (where he did a sensational impression of Bert Williams), and made numerous appearances in recent shows here and abroad that have showcased the neglected art of tap dancing. Currently he is touring with “Bubbling Brown Sugar” in Europe and, after returning early next year, plans to appear in a musical adaptation of the life of Bill Robinson.

When Harlem Was Mecca

Talking to Honi Coles is like taking a guided tour of the past five decades of black entertainment.

“The scene has changed so much in recent years,” he muses. “In the 30’s there was much more of a sense of, how should I say, togetherness among black performers. There’s a wide gap now between me and, well, Bill Cosby. He’s up there, you know, making big money-essentially separated from the average black performer. Then, we were all practically on the same level. For one thing, everybody lived in Harlem; that was the mecca. Every black performer in the business either lived permanently in Harlem, or lived at the Theresa Hotel or one of the other four or five decent hotels there, when they performed in New York. And we all hung out together, went to the same speakeasies or after-hours joints. We were much closer.

“Another thing is that you had to be a complete performer then. You had to learn every facet of the business, I mean, dancers were always used in the bits-sometimes even the musicians. You didn’t just come into a show and do your dance routine. It was expected that you’d be in the comedy bits. This was the beginning of your education as a comedian. It’s how I got into it. When you’re working a bit with comedians like Dusty Fletcher or Tim Moore, who later went on to the ‘Amos ‘n Andy Show,’ you’re learning timing; you’re learning the whole spectrum of how comedy works. That’s the tragedy of show business today; the kids have no place to learn, expand and become involved in the whole thing.

“That’s why I’ve always said there is a close relationship between dancing and comedy, particularly with the older comedians. And most people don’t realize it. When I worked with Bert Howell at the Roxy in the late 30’s, I had to be more comic than straight man. He was a very proper West Indian, and a clever man-played violin, ukulele and sang. He broke me into being a half way decent comedian. He had worked as a straight man with people like Frank Radcliffe, Bud Harris and Sydney Easton-comics of the time-so it was a teacher-pupil relationship; but after awhile we weren’t bad. He taught me the proper timing, delivery and so forth-refined what I’d learned as a dancer working in bits. Before long I thought I knew what I was doing up there.

“Charlie Atkins and I added some comedy to our act also, but with Bert, we actually stood up and told jokes. Things like, well, Bert might say, ‘Let’s play Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.’ And I’d say, ‘I don’t know it.’ Then he’d say, ‘I demand that you play it.’ I’d answer, ‘De man, don’t know it.’ You know, that kind of loose comedy. We also did a lot of traditional vaudeville skits. The comedy in the Coles-Atkins act was just patter and mime. It started when we were at the Lookout House in Covington, Kentucky. Most of the people who came in to the show were from the gambling casino-they’d lost their money and, as you’d expect, weren’t too happy. So Charlie and I began adding quips to our soft shoe routine, trying to liven things up. We developed that to a point though, where we were working with Pearl Bailey at the Coconut Grove in Los Angeles and she came in and told us to cut out the comedy. We were getting too many laughs. Pearl was like that-a beautiful woman, but you never knew how she would feel. You’d come in one night and she’d love you to death; the next night she’s not speaking to you. We kept the little comedy bit in the routine and she never said another word about it.

The Purest Dancer Around

“Anyway, there were many dancers, people known as dancers, who crossed over into comedy. Bill Robinson, as you know, was a great dancer, probably the purest dancer around, but he learned to be a comedian on the TOBA circuit. He was a friend right up until his death in 1949-a tremendous talent and a very complex person. He wasn’t educated-in fact, Fanny Robinson taught him to read and write-but proud as he could be. He was a poolroom man, card player, gambler, and probably the most fastidious dresser that ever lived.

“A lot of people didn’t understand him. For instance, he’d tell jokes about ‘old colored women,’ but he always talked about ‘white ladies.’ Still, there was an incident in Louisville, Kentucky, when I was in the army, where one of the white stagehands patted a black chorus girl on the behind. After the show Bill told everybody to stay and read the riot act to the stagehands. This was unheard of in the South at that time, but he did it… And, although some people criticized him for the Tom roles in the pictures, he was extremely elated about those movies. He was the happiest man in the world doing things like that with Shirley Temple. Part of it was the generosity that black entertainers showed to whites. We were so happy somebody wanted what we did; we were ready to just give it away. Bill enjoyed teaching Shirley and many other Hollywood stars how to dance; it was the way he was. He was a brilliant man and a complete entertainer, not just a dancer.

“John W. Bubbles of Buck and Bubbles was another great dancer who also did comedy. He started out just dancing, but developed a comedy routine before long. Buck and Bubbles was the next black act, after Bert Williams, to star in the Ziegfeld Follies. And they had the same problem Bert had-they were so good the white acts objected to following them. Buck was a small, funny guy who played the piano, and Bubbles was taller-had a certain majesty about him-and was the greatest dancer in the world. They were sensational. Most all of our present day dancing is patterned after Bubbles. He introduced dropping heels, for instance. See, most dancers of the time were always up on their toes, but Bubbles added that heavy syncopation with the heels. That’s where the rhythm of be-bop came from; the musicians picked it up from the dancers. At first, in the early 30’s, drummers were confused by the dancers’ rhythm, but they picked up on it and be-bop came out of it later. Bubbles, though, despite his dance talent, had to be a comedian also.

How Hope Started…

“And most of the great black comedians of that time had started out as dancers. Bert Williams, Dusty Fletcher, John Mason, Johnny Lee, Pigmeat Markham, Moms Mabley, Mantan Moreland, Eddie Anderson or Rochester, even Sammy Davis, Jr. and people like Red Skelton and Bob Hope… During that time a performer had to do everything in order to make it; Hope was strictly a dancer when he started. I saw him in “Ballyhoo of 1932” with Willie and Eugene Howard-two of the best white comics in the business at the time-and Bob Hope was a stooge in the box. A black girl who worked with me in “Humming Sam,” her name was Baby Cox, absolutely stole the show. She stopped it cold. It was funny because they had warned her there would be no bows. ‘Just do your act and get off,’ they told her, which was typical of the treatment of blacks working in integrated shows then. So when she stopped the show and the applause started, she just went on upstairs. The Howards were supposed to follow her, but nothing could go on with all that clapping. When they asked her to come down, she refused; she was an arrogant little girl. Didn’t come down until five minutes later. That’s the way it was in those days… When I mentioned that show to Bob Hope at a recent Dick Cavett Show, he fluffed it off, so I dropped it. But that’s how Hope started…

“Nowadays a lot of people criticize the comics from those times. But people forget how different things were. For instance, when I first came to New York, another of the Miller brothers was working at the original, uptown Cotton Club, and he invited us backstage. It was the only way I got to see it, I never worked there. It was an all-black show, and had all black help, except for the Chinaman in the kitchen. But there were no blacks in the audience-none. And we had no resentment at that time; it was normal. That was the way of life. If you were brought up in that period, there was no reason to even think about changing things. Comics thought the same way, they reflected the times.

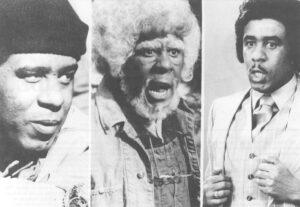

Running From Ghosts

“Most of them were totally natural, what you saw on stage was the same thing you saw on the street. Stepin Fetchit didn’t consciously make fun of black folks; he was acting out his sense of what black folks were about. It wasn’t a matter of doing an impression of a black man, that’s the way it was. At that time that’s all a black man could do; he was either a waiter or a porter, or in some subservient position. Mantan Moreland also-with the buck eyes, gleaming teeth, running away from ghosts-there was some truth to that.

“People forget, we didn’t survive because we were the greatest intellectuals in the world. Most of us couldn’t even go to school, then. You know how we survived? Through humor and manipulation-subterfuge. Most comedians were actually being themselves, reflecting that manipulation. They weren’t acting. Louis Armstrong was criticized for Tomming, for instance, but that’s the way Pops was off the stage. He was the most entirely natural man I ever met in my life. What you saw onstage was him; he acted the same way in the joints after the show was over. Anyone who calls Pops a Tom has to be among the dumbest individuals alive. It’s pathetic that people don’t really understand that. I resent all the criticism of those comics, because the critics don’t take into consideration the era in which they grew up.

“Another thing is that comedians like Step, Mantan or Tim Moore and Johnny Lee, who both worked on the ‘Amos ‘n Andy Show,’ were doing the same things they did in the movies and on TV when they worked before all-black audiences on the stage. Nobody complained then. Mantan used to roll his eyes and tell ghost stories, most of the skits were in that vein, and black people loved him. I worked with him and with Tim Moore. Although Tim was probably the most intelligent comedian around, then-he was the only one I knew who had a college education-many of the things he did as Kingfish were in his act on stage. Blacks laughed at it, and loved it. It was only after it was on TV and exposed to whites that people started complaining.”

That Vaudeville Style

“Who were the best of those older comedians?” I ask.

“Well, I never saw Bert Williams. So I’d have to say John Mason was probably as funny as anyone I’ve ever seen in my life. And just as funny off stage as on. He worked during the 20’s and 30’s at the Harlem Opera House, the Apollo, and other black clubs. Always worked in blackface. He was a very funny man, a great faller, you know, pratfalls, and very quick with his lines, excellent timing. Now Flournoy Miller, who I saw work with Mantan, was a very funny droll comedian. You know, the kind of delivery that Step and Willie Best had. But I prefer the Mason approach, you know, ding-ding-ding. That type of comedy has always appealed to me more.

“Tim Moore was also an extremely funny man. I used to do sketches with him and couldn’t stop laughing. I’m supposed to be in the act, and I’m cracking up. And, another comic, Allan Drew, was the fastest one-liner man in the business. Milton Berle and all the white comedians used to come up to Harlem to watch him. He was so fast; you’d laugh three gags later. He worked in the 20’s and 30’s also, had the cigar like W.C. Fields. He never became a star, never really made it, but he was the quickest comic alive, including Hope; Berle, Henny Youngman. He quit for a while went back to Chicago and became a policeman. I guess there wasn’t a call for that type of black comic. Later, he came back to New York and worked some, but he died a few years ago.

“You have to remember, though, these were comics from another era. They were all within that vaudeville style… If you compare them to today’s comics, well, for instance, a performer like Step typified the white man’s conception of the average black man, whether he intended to or not; a Richard Pryor doesn’t. Step had to conceal the irony behind his actions, or maybe he didn’t even know about it. Pryor makes it obvious; he can do that, the times have changed. That’s the difference.”

© 1979 Mel Watkins

MEL WATKINS is currently interviewing and. writing from Los Angeles for his APF project on Black Humor from Stepin Fetchit to Richard Pryor.