As Moscow’s satellites spin wildly out of control, all the world’s eyes are focused on Checkpoint Charlie, Wenceslas Square, and Europe’s leap into the post-Yalta future. But what about the rest of the world? If the Cold War is ending in Europe, can the Third World be far behind? With pieces of the Berlin Wall on sale at Bloomingdale’s and the Red Army Chorus serenading the White House, the Soviet threat just doesn’t pack the punch it once did. Trouble spots remain, of course; witness the recent fighting in El Salvador. In the future, though, these “regional conflicts” will seem just that–matters of local strife–rather than theaters of superpower confrontation. On everything from nuclear proliferation to saving the Amazon, Washington and Moscow will find more in the Third World that brings them together than drives them apart. In a sign of things to come, the RAND Corporation recently held a joint U.S.-Soviet conference on combating international terrorism.

So, with the Soviet threat fast receding, the U.S. can finally cut back its presence in the developing world, right? Wrong. Remarkably, a consensus is now building in Washington that the end of the Cold War, far from diminishing our role in the Third World, will actually increase it. In this view, the division of the globe between East and West, while causing friction, imposed a template of order on a chaotic world. Now, with tensions relaxing in the North, the lid is fast coming off the South, freeing the yearning, churning masses there to press their demands. Anarchy is the likely result-unless, that is, the West intervenes.

Admiral William Crowe, the recently retired chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, summed up the new wisdom in a December 7 Washington Post op-ed piece. “Regional rivalries and instabilities in the subcontinent, the Persian Gulf, the eastern Mediterranean and in Latin America show no sign of abating and may very well intensify,” the admiral wrote. “International terrorism and drug trafficking are increasing. Complicating the picture is the proliferation of sophisticated weapons throughout the Third World.” In short, Crowe asserted, “the necessity to protect our interests in an uncertain world will not disappear….”

Of all the threats cited by Crowe, one stands out in the minds of U.S. policy-makers: drugs. Drugs are well on their way to replacing the Soviet threat as the cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy. In Washington today, cocaine, heroin, and marijuana are talked about in the same lurid tones once reserved for Fidel, Che, and Mao. Consider, for example, President Bush’s National Drug Control Strategy, commonly known as the Bennett Plan. It states:

The source of the most dangerous drugs threatening our nation is principally international. Few foreign threats are more costly to the U.S. economy. None does more damage to our national values and institutions or destroys more American lives. While most international threats are potential, the damage and violence caused by the drug trade are actual and pervasive. Drugs are a major threat to our national security.

To the “greatest extent possible,” the report declares, “we must…disrupt the transportation and trafficking of drugs within their source countries….”

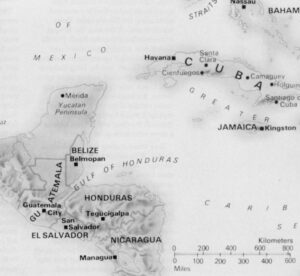

Most of those countries, of course, are located in Latin America. In a sense, the Bennett Plan provides an updating of the Monroe Doctrine, establishing the principle of hemispheric intervention in the name of fighting drugs. This principle–call it the Bush Doctrine–already is being put into practice. In Colombia, American planes and helicopters are being sent out on raids against the Medellin Cartel. In Bolivia, U.S. military advisers are training police units in jungle warfare. In Ecuador, Venezuela, and Brazil, the U.S. is establishing elaborate surveillance networks to trace the flow of precursor chemicals. The U.S. has created a Serious Crimes Squad in Belize, built radar installations in the Bahamas, and formed a high-level government committee in Jamaica to uncover clandestine airstrips.

The new buildup is most apparent in Peru. Today that country has much the same feel El Salvador did in the early 1980s. Military transport planes fly in regularly from Southcom, bringing trainers, machine guns, and ammunition. Congressional delegations frequently roll into town, eager to see the drug war up close; Stephen Solarz alone has come several times in the last two years. General Paul Gorman, the former Southcom commander who so enthusiastically carried out Reagan policy in Central America, recently passed through in his new role as an adviser to William Bennett. Counter-insurgency buff Andy Messing, a champion of the contras and a friend of Oliver North, spent a week here over the summer. All have come to see the paramilitary base that the U.S. is building in the heart of Peru’s coca-growing region. Staffed by DEA agents and former Special Force operatives, the base is the first of several that the U.S. plans to build in Peru as the drug war heats up.

At first glance, such efforts would seem all to the good. Unlike the Soviet threat, which was used mainly to fan false fears–Grenada, the mighty giant-killer, etc.–the drug menace is real. Cocaine is entering the U.S. like a silent invading army, polluting our youth, corrupting our institutions, overwhelming our cities. Under President Reagan, the war on drugs remained largely a rhetorical device. Now, at last, Washington is girding for battle. Unfortunately, the current burst of activity seems unlikely to accomplish much. Overseas, at least, the war on drugs is shaping up as a sure loser.

To understand why, it’s necessary first to examine the nature of the American buildup. Directing the anti-drug campaign abroad is the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics Matters (INM). Long considered a backwater, the bureau is rapidly emerging as one of Foggy Bottom’s most aggressive units. INM controls an Interregional Airwing made up of more than 50 aircraft, including fixed-wing airplanes, C-123 cargo transports, and Vietnam-era Huey helicopters. These aircraft are used to ferry troops, move supplies, and, most important of all, spray crops. INM’s chief goal is to eradicate coca, marijuana, and opium from the face of Latin America. To that end, it is pelting crops in Colombia, Guatemala, Belize, Jamaica, and Mexico, and the bureau soon hopes to add Peru to the list.

While INM planes control the skies, the Drug Enforcement Administration is supplying the ground troops. Traditionally, the DEA has concentrated its efforts at home, but, with Washington’s growing focus on the source countries, the agency has beefed up its presence in Latin America. Today, more than 150 agents are at work in 17 countries. Concerned in the past mostly with gathering intelligence, the DEA is more and more engaged in paramilitary activity. Under Operation Snowcap, agents receive instruction in Spanish, then attend Army Ranger school at Fort Benning, Georgia. Upon graduating, they are dispatched to the coca-rich regions of South America, where, armed with machine guns and jungle knives, they stage helicopter raids on processing labs and clandestine airstrips.

The CIA, too, is expanding its presence in Latin America. New agents are being assigned to Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and other key source countries. In Langley, the agency has set up a Counter Narcotics Center to collate the mass of data pouring in from agents, informants, wiretaps, radar, satellites, and foreign police departments. Sifting through all this are some 100 agents, diligently working to chart the far-flung operations of the drug cartels.

No war would be complete without the Pentagon, of course. Even as Defense Secretary Dick Cheney announces major cuts in defense spending, the U.S. Southern Command in Panama is preparing to step up its activities throughout Latin America. General Maxwell Thurman, the commander of Southcom, has already made several trips to the Andean nations, sounding out local military and police chiefs on their needs. Arms shipments to the region are being sharply stepped up. In 1988, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia together received only $3 million in military aid; in 1990, that figure will rise to $170 million. Teams of Special Forces advisers, too, are being dispatched to the region in growing numbers.

Even agencies with little history of involvement in Latin America are enlisting in the drug war. The U.S. Customs Service, for instance, has dispatched its agents throughout the continent to assist local forces in sealing borders, controlling highways, even training dogs to sniff parcels at airports. The Coast Guard has sent mobile training teams to instruct local policemen in river interdiction; in 1988, more than 600 people received such training, most of them from Latin America. The U.S. Information Service, meanwhile, is holding workshops throughout the continent, educating journalists on the evils of drugs and the need to fight them. “Drugs have become the number-one priority of our agency,” says a USIS official in Peru.

At long last, then, Washington is mobilizing for the war on drugs. Unfortunately, in waging it, we’re about to commit all the same errors we made during the war on communism. First off, there’s the Friendly Dictator Syndrome. In combating Marxism, Washington frequently befriended tyrants like Somoza and Duvalier because of their steadfast opposition to communism. Now we’re embracing equally unsavory figures because of their tough stand on drugs.

Haiti is a good example. General Prosper Avril, installed as president in a 1988 military coup, repeatedly went back on his promises to hold free elections and respect human rights, before he was forced out of office. He did, however, move aggressively against cocaine traffickers active in Haiti, and the U.S. signaled its approval. “The [Avril] government…has expressed a firm commitment to cutting the flow of illegal drugs through Haiti,” the State Department observed in its 1989 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report. “Despite political turmoil” i.e., disappearances, killings, and popular clamoring for democracy–the Haitians have maintained drug interdiction efforts and cooperated closely with U.S. authorities.”

In Guatemala, the security forces have such a sinister reputation that even the Reagan Administration had to keep a discreet distance. Recently, however, Guatemala has become a major transit point for U.S.-bound cocaine and a producer in its own right of opium and marijuana. Today, U.S. agents are active in Guatemala, patrolling the international airport, tracking the flow of precursor chemicals, and spraying hundreds of hectares of poppy and cannabis. In all of this, the Guatemalan police and military have proved dependable allies. “The U.S. Embassy,” the State Department report notes with satisfaction, “has established close relation relationships with Guatemalan law enforcement authorities.”

Such developments are especially dismaying in light of our recent unhappy experience in Panama. For years we overlooked Manuel Noriega’s involvement in drugs because of his usefulness in the war on communism. Now that we’re against drugs, that association has proved intensely embarrassing. Nonetheless, the U.S., in the name of fighting drugs, is now doing business with other Noriega-like figures. The old double standard has returned in new guise.

Washington’s flowering relationship with anti-drug strongmen points to a broader flaw in U.S. drug policy–a predilection for military solutions to problems that are social and economic in nature. The cocaine industry has established such deep roots partly because of the severe economic crisis gripping the Andean region. Faced with soaring prices, poor employment prospects, and government neglect, hundreds of thousands of peasants have turned to coca as the one dependable means of support available to them. In the view of most Latin American experts, only economic development and crop-substitution programs offer a realistic hope for weaning farmers from coca.

Thus far, however, the U.S. has shown little interest in the economic aspects of the cocaine problem. The Bennett Plan is full of references to things like “interdiction,” “destruction,” “dismantlement,” and “eradication”; by contrast, rural development and economic aid receive only passing mention. Today, U.S. drug-control representatives spend far more time with generals and police chiefs than with agrarian planners and peasant leaders. Basically, we’ve gotten our priorities backwards. Just as ten years of military intervention in Central America have failed to bring peace to the region, so, too, is our current reliance on interdiction and law enforcement unlikely to stem the flow of cocaine into the United States.

This is the plain lesson of recent events in Colombia. After presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galan was gunned down by narco hitmen on August 18, President Virgilio Barco declared war on the Medellin Cartel. Intent on putting the traffickers out of business once and for all, Barco unleashed his security forces in a massive nationwide campaign against the cartel’s leaders. Eager to help, President Bush rushed Colombia $65 million in emergency military aid, including 2 C-130 transport planes, 8 A-37 jets, 12 helicopters, 20 jeeps, ambulances, radios, and machine guns. Teams of Colombian soldiers and police swooped down on the traffickers’ estates, seizing hundreds of planes, trucks, boats, and radio transmitters, not to mention a huge arsenal of weapons. It was the most intensive anti-drug offensive in Latin American history, and it succeeded in bringing Colombia’s drug business to a standstill.

Only temporarily, though. In a matter of weeks the cartel managed to reconstitute its trafficking networks, and by November the trade was back to normal. Today cocaine is entering the United States in record quantities. In the last few months, U.S. drug agents have seized 20 tons of cocaine in a warehouse in Los Angeles; 9 tons in a house in Harlingen, Texas; 6 tons aboard a Panamanian freighter; and 5 tons on a boat off Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. Such unprecedented hauls are causing U.S. drug agents to revise radically upward their estimates of worldwide cocaine production. American cities are so glutted, in fact, that Latin American traffickers have turned their attention to Europe, hoping to develop new markets where they can dump their powdery surpluses.

As the failure of the Colombian offensive sinks in, America’s drug warriors will no doubt call for a redoubling of our efforts in that country. If 12 helicopters aren’t enough, well, then, let’s send 24. No matter how many helicopters we send, though, the results are likely to remain the same. Even if we somehow succeeded in dismantling the Medellin Cartel–a most unlikely development–the narcos would simply relocate their facilities elsewhere. Already, cocaine processing labs are being moved from Colombia to Peru, Ecuador, and Brazil’s vast Amazon.

Today, Latin America’s cocaine industry extends over an area nearly as large as the continental United States. Covered by forests, crisscrossed by mountains, riven by ravines, the region is one of the most inaccessible in the world. Economically, the cocaine business employs millions of people and generates tens of billions of dollars in revenues. The narcos have amassed huge stockpiles of sophisticated arms and maintain private armies that in some cases dwarf those of the established security forces. Add in weak governments that barely control their national territories, and the war on drugs seems inherently unwinnable.

It’s enough to make one nostalgic for the Cold War.

©1990 Michael Massing

Michael Massing is a freelance writer investigating America’s counterinsurgency efforts.