The signs are visible everywhere in Guatemala. Newspapers carry frequent accounts of grisly execution-style murders. Immigration authorities report a surge in the entry of Colombian nationals. Deluxe apartment buildings and office complexes rise dramatically on the outskirts of Guatemala City. A newly chartered bank in Coban, 70 miles north of the capital, is doing a brisk business despite not having formally opened its doors to the public.

Drugs have come to Guatemala. The country has lately replaced Panama as Central America’s foremost trafficking center. In the mountainous region bordering Mexico, hundreds of Guatemalan peasants are cultivating opium poppies. Converted into paste, the crop is sold to Mexican traffickers for processing into heroin. Three years ago, poppies covered about 600 hectares of land; today, the figure is 2,000 hectares and rising sharply, making Guatemala the fourth or fifth largest opium producer in the world.

Drugs have come to Guatemala. The country has lately replaced Panama as Central America’s foremost trafficking center. In the mountainous region bordering Mexico, hundreds of Guatemalan peasants are cultivating opium poppies. Converted into paste, the crop is sold to Mexican traffickers for processing into heroin. Three years ago, poppies covered about 600 hectares of land; today, the figure is 2,000 hectares and rising sharply, making Guatemala the fourth or fifth largest opium producer in the world.

Cocaine is an even bigger business. Every month, an estimated four tons of cocaine pass through the country on their way to the United States.

The trade is controlled by the Colombian drug lords, and the hallmarks of their work-corruption, murder, and drug addiction-have begun surfacing everywhere in Guatemala. “We have so many problems in Guatemala civil war, poverty, and the like,” sighs Edmond Mulet, a member of Guatemala’s National Assembly, “and now this.”

All of this has dismayed U.S. officials just as they were toasting the end of the Soviet threat in Central America, a new enemy has emerged, one posing an even more direct threat to the nation’s wellbeing. And Washington is quickly mobilizing to confront it. Ten years ago, the State Department chose El Salvador as the country in which it would draw the line against communism; today, it has selected Guatemala as the test site for the drug fight in Central America.

Guatemala’s rise as a trafficking center is due, ironically, to one of America’s rare successes in the drug war. In the early 1980s, most of the cocaine entering the United States came through southern Florida. Shipments were flown from Colombia to remote islands in the Caribbean, then transferred to small high-speed boats and rushed to coves and inlets along the Florida coast. Determined to seal off the area, the Reagan administration set up the South Florida Task Force, a highly specialized unit bringing together agents from Customs, the Coast Guard, and the Drug Enforcement Administration, among other agencies. Using radar, patrol boats, and spy planes, the task force erected an electronic curtain along the Florida coast, making it much harder for drugs to enter. Stymied, the drug lords began looking for a more vulnerable point of entry.

They found it along the U.S.-Mexican border. With millions of vehicles crossing into the United States every day, Customs could check only a fraction, and smugglers were able to enter with ease. Cocaine was now flown from Colombia to northern Mexico, then transferred to cars and trucks and driven across the border. This gave rise to a new problem, however. The lightweight Beechcraft and Cessna planes used to transport the drugs did not have sufficient fuel capacity to make the 2,500-mile journey non-stop. A transshipment point was needed.

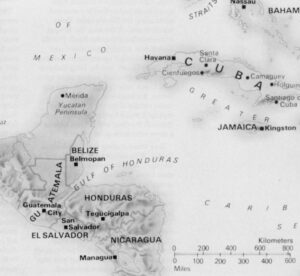

Guatemala was ideally suited. Situated roughly midway between Medellin and the Rio Grande, the country was within easy flying distance of both. Wild and rugged, with craggy highlands, steep valleys, and thick vegetation, Guatemala offered traffickers excellent ground cover. Porous borders made it easy for smugglers to enter, and, once inside, weak drug laws and a feeble judicial system made imprisonment highly unlikely.

Another important asset was the hundreds of small dirt airstrips that dotted the Guatemalan countryside. Most were located on the country’s southern coastal plain, a lush agricultural region covered with coffee and cotton fincas. The owners of these estates generally live in Guatemala City, flying out several times a week to inspect their investments. To accommodate the flights, each finca has its own runway. Paying $25,000 or more per flight, the drug cartels were able to procure the use of these strips for their own planes. Arriving mostly at night, the planes could easily avoid detection by the country’s lone radar facility, a weak device located at the international airport in Guatemala City.

Today, several drug flights touch down every week. In some cases, the planes simply refuel and immediately resume their journey. More commonly, though, the flights are met by work crews, who unload the cargo and transfer it to trucks and vans for transport to safe-houses. After a decent interval, the bundles are driven to a port facility or to the airport in the capital. Then, by air or by sea, the cargo resumes its northward journey. Such intermediate steps afford the traffickers added protection against detection by the authorities.

With local conditions so conducive to drug trafficking, fighting it would seem doomed. Nonetheless, the United States is determined to try. Already, U.S. spray planes are attacking Guatemala’s poppy fields with the herbicide Round-up–part of America’s largest aerial eradication program in Latin America. FBI agents are training Guatemalan detectives in investigative techniques, and Customs officials are conducting courses in maritime interdiction. The local DEA staff has expanded to five agents and is about to add one more.

To date, though, the campaign has had limited effect. The aerial eradication campaign, while destroying hundreds of acres of poppies, has simply forced growers further into the hills; overall, production is booming. Similarly, seizures of cocaine are up, but so is the volume passing through the country. One major problem is the Guatemalan Treasury Police. The Guatemalan government has designated it the lead agency in the drug war. However, the unit is poorly trained, inadequately equipped, and notoriously corrupt–no match, in short, for the drug lords. In the end, there’s only one institution in the country really capable of taking them on, and that’s the military.

The military, though, has strong reservations about joining the drug fight. Guatemala soldiers are very poorly paid, making them highly susceptible to bribes. Already, a number of military officers, including quite senior ones, have reportedly become involved in the drug trade. What’s more, the military has its hands full fighting Guatemala’s guerrillas. Almost thirty years old now, the insurgency has intensified over the last year, and the army-already suffering many casualties-is loath to take on another, even more elusive adversary.

However, the United States-more concerned now about drugs than guerrillas-is pressing the military to join the fray. In that effort, it has found a valuable ally in General Hector Gramajo, Guatemala’s minister of defense from January 1987 until May 1990. U.S. officials regard, Gramajo as a model general. A graduate of training programs at Forts Benning and Leavenworth, he speaks fluent English and mixes easily with Americans. As defense minister, Gramajo toured the country’s military bases, lecturing his men on the importance of civilian rule. He traveled frequently to Washington to lobby liberal congressman and once even testified in Congress, telling members of the House Foreign Affairs Committee about his commitment to human rights.

“Gramajo is as responsible as anybody for pushing the army into becoming more professional,” says one U.S. official. “He’s tried to form an apolitical officer corps and inculcated a deference to civilian rule in the top leadership.”

Gramajo’s relationship with the United States was sealed on May 11, 1988, the day a group of hard-line colonels tried to overthrow the government of President Vinicio Cerezo. Branding Cerezo a “communist,” the officers expressed outrage at the surge in popular political activity during his term and demanded an immediate crackdown. Gramajo would not go along, however. Declaring his loyalty to the constitution, he called for an end to the revolt, and it soon collapsed.

A year later, the officers tried again. This time, the rebels surrounded Gramajo’s house and kidnapped his wife and three of his children. Once more, Gramajo refused to give in, and the uprising again failed. (His wife and children were released unharmed.) More than twenty officers were discharged from the army, and seven were brought before a military tribunal and sentenced to prison. Guatemala’s fledgling democracy was preserved.

U.S. officials were gratified. For years they had been promoting civilian rule in Guatemala, and now the defense minister himself had intervened to protect it. Eager to show its appreciation, Washington quickly strengthened its ties to the Guatemalan military. From 1977, when Congress suspended all military aid to Guatemala because of its human-rights record, until 1986, when Cerezo was installed as president, the United States had kept its distance from Guatemala’s armed forces-one of the most brutal in the hemisphere. Now, however, the military was back in favor, and the Pentagon began offering whatever assistance it could. Green Beret advisers came to train Guatemalan special forces, U.S. Army engineers came to build roads, and National Guard medical units came to undertake civic-action missions. Washington also approved the sale of 20,000 M-16 rifles to Guatemala-the first major sale of lethal weapons to that country in a decade.

In late 1989, the bill came due. With drug trafficking on the rise in Guatemala, U.S. officials desperately wanted help in confronting it. General Maxwell Thurman, then the commander of the U.S. Southern Command in Panama, met with Gramajo and other high-ranking officers in Guatemala City, urging them to join the drug war. U.S. Ambassador Thomas Stroock, who had a close relationship with Gramajo, pressed the matter at every opportunity. Eventually Gramajo relented, and elite elements of the Guatemalan military began working closely with U.S. drug agents.

Encouraged by this initial cooperation, U.S. officials prepared to escalate their anti-drug efforts in the country. If all goes according to plan, the United States in 1991 will:

- Install a new radar station on Guatemala’s southern coast;

- Train Guatemalan soldiers to analyze the data produced by that radar;

- Form SWAT teams to swoop down on suspect aircraft while they’re on the ground;

- Provide ten to twenty high-speed boats to the Guatemalan navy to improve its patrol abilities;

- And mount major sting operations against the local activities of the Medellin and Cali cartels. In short, Guatemala is about to become a major new front in the war on drugs.

That, though, could have serious consequences for the country’s human-rights record. Guatemala is currently undergoing its worst wave of political violence since the early 1980s. Murders and disappearances have become commonplace, and bodies bearing signs of severe torture are appearing on roadways and riverbanks, much as they did a decade ago. Students, teachers, unionists, and human-rights workers all have come under attack.

Much of the violence has been traced to the Guatemalan military. In Guatemala it’s been widely reported that Gramajo, in putting down the May 1988 coup attempt had to accede to the rebels’ demands for tougher action against popular organizations. Once unleashed, hard-line officers went on a rampage. The State Department’s report on human rights in Guatemala for 1989 rites “credible reports of security forces personnel and political extremists engaging in extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and other serious abuses.”

Gramajo did nothing to investigate these crimes; indeed, not a single military officer was prosecuted during his three-plus years as defense minister.

The unit most frequently implicated in these crimes is military intelligence, known as G-2. The military’s nerve center, G-2 maintains a network of informants extending into every hamlet and barrio in the country. G-2 taps telephones, monitors passports, and infiltrates political organizations. Its primary purpose is eliminating subversivos.

“G-2 is actively involved in coordinating kidnapping cases as a way of staying on top of the eradication of leftist cell-building in the capital and parts of the countryside,” says a university professor with close ties to the army. Some of the victims are people actually collaborating with the guerrillas; others are simply political activists deemed a threat to the status quo.

All in all, little takes place in Guatemala without G-2 members knowing about it. That includes drug trafficking. “Military intelligence is by far the best source of intelligence in the country,” says a Western diplomat, “so it’s the best source at getting intelligence on drugs as well.” Already, both the DEA and the CIA are working closely with G-2 to obtain data about local drug operations. If the U.S. goes ahead with its plans for intensifying the drug war, it will become even more reliant on G-2 for intelligence.

U.S. officials are aware of the risks involved. “We’re going to have to make a decision about the army and drug trafficking,” says one official. “We’re going to have to weigh the equities-on one side, their less-than-sterling record on human rights, and, on the other side, the fact that they’re the most efficient force available to help us interdict drug trafficking.” Clearly, in view of G-2’s record, the U.S. can’t have it both ways.

©1991 Michael Massing

Michael Massing, a freelance writer, has been examining U.S. efforts in fighting drugs in Central America.