Attitudes toward old age in Japan depend somewhat on what one thinks about bowling, baby carriages, hamburgers and democracy. All are, of course, post-war innovations introduced by the U.S. Occupation. Any of them, the influx of democratic ideas in particular, have become examples of American influences that are responsible for the bad/good (check one) status of life in Japan today.

If it seems confusing, the Japanese themselves are caught up in a paradox. They are struggling, at times overtly, with deep-seated traditions that clash with the by-products of tremendous economic growth. (Problems of pollution and a housing shortage that discourages multigenerational living are a few examples.)

The older generation has had to make a gigantic psychological shift from growing up in the early century of the Meiji Restoration, with its emphasis on militarism, authoritarianism and emperor-worship to the defeatism of World War II and the exposure to individualism. Thus, democracy to Chiyoko Terada, 75,of Tokyo, means, simply, “Going to parties where I can sing and dance. When I was married,” said the kimono-clad, army widow, “my husband didn’t take me anywhere.”

Mitsugu Yamashita, 22, and a student of sociology at Tokyo’s Sofia University, sees democracy as “The freedom to do anything. Prewar,” he explained, during a social hour at the home of classmate Jun Takenaka, “we had to follow the aged. Now we don’t have to.”

Dr. Reiko Takenaka, 45, and Jun’s mother, slapped her son’s knee affectionately and feigned annoyance. “He wants to be independent,” she said. Youth doesn’t want to consult parents about marriage or a job. I don’t expect to live with him when I am old as my mother does now with me.” Hesitating for a moment, for fear of insulting the American visitor, she added candidly, amidst much laughter, “The U.S. is responsible for the situation in Japan today.”

It was a situation, she explained, which allowed some adults to “interpret freedom as not giving to their parents. Of being independent and leading separate lives. Before the war, there were no problems,” said the diminutive figure dressed in a tailored, beige, two-piece knit dress. “The aged were certain the oldest son would inherit their property and were assured he would look after them. Now, the property is divided, the daughter-in-law is more assertive and the younger couple lives separately.”

According to an Asian proverb, the “hateful things” are “earthquakes, thunder and the Old Man. Nonetheless, obeisance, indeed filial piety are the cement that binds together Japanese society. Despite wholesale migrations to industrial centers, which have changed the country from 80 per cent rural to 80 per cent urban in 25 years, the aged have not been totally abandoned. (By comparison, in Sweden, urbanization has cut emotional as well as physical ties.) In the absence of physical reassurances, there are psychological and financial supports. Anything less would be a most unfilial form of behavior and anathema to a carefully nurtured way of life.

Because of population density (four-fifths of the total 103 million persons live in an area the distance between Chicago and Detroit), there is a rigid code of conduct based on inter-personal links. Anthropologist Ruth Benedict described Japan as a “vertical society.” The code allows little lee-way for individual flamboyance, or of “going it alone” in the U.S. sense.

Once “out of step,” it is difficult to find the cadence again. To wit, the negligible crime rate in a city of 11.5 million like Tokyo. A criminal can hardly claim a “proper place” and a sense of “place” has been ingrained into the Japanese psyche from birth.

The sense of relationships, a dependence on people rather than “things” has also saved the Japanese, to date, from behaving like other industrial giants. In the U.S., we have become selfish, self-centered and acquisitive and negligent of aging parents if they cost us money. If you ask some Americans who can afford a second car if they had thought of contributing the money to a parent’s comfort or joy instead, they will look at you blankly and, if honest, say they hadn’t thought of it. The response is typical of a society brought up with a “me first” attitude. We are taught early in life to steer our own course and not feel obligated to our elders. The notion shocks the Japanese. Tradition has decreed otherwise.

Thus the proliferation of goods (from French cognac and fashions to American records), gadgets and a Mc Donald’s hamburger outpost don’t deter the Japanese from their basic life attitude. It was I, a visitor with Western values, who got sidetracked by the mixture of old and new and thought, initially, that Japan had become Americanized.

It was inconceivable to me to find an isolated farmhouse outside Kyoto with an old-fashioned charcoal brazier for heating and a shrine to the god of fire along with a television set and an electric rice cooker. Or, in town, to understand how a mod, mauve-kimono-clad grandmother could accept prostrt4tions from her daughter-in-law and then go off to bowling practice. Or in a non-Christian land to see the hullabaloo over Christmas complete with mini-skirted female Santas bowing shoppers in and out of department store entrances. At that, it wasn’t a demonstration of women’s liberation, but of customer veneration.

It was inconceivable to me to find an isolated farmhouse outside Kyoto with an old-fashioned charcoal brazier for heating and a shrine to the god of fire along with a television set and an electric rice cooker. Or, in town, to understand how a mod, mauve-kimono-clad grandmother could accept prostrt4tions from her daughter-in-law and then go off to bowling practice. Or in a non-Christian land to see the hullabaloo over Christmas complete with mini-skirted female Santas bowing shoppers in and out of department store entrances. At that, it wasn’t a demonstration of women’s liberation, but of customer veneration.

Lulled by this feeling of being “at home,” except for a few exotic aberrations, I made the mistake of walking on the right side of the sidewalk as a rush-hour crowd exited in my path from a subway station. As I got pushed aside and elbowed in the stomach, I remembered the Japanese walk on the left, not the right, and had my first lesson in on and “proper place.”

Courtesies are extended in vertical relationships; riot horizontally or to strangers such as myself. According to the Japanese interpretation of Confucianism, there are five key relationships and obligations within each: superior-inferior, father-son, elder brother-younger brother, husband-wife and friend-friend. They extend through life: within the family, in school, job and social affiliations and even hobby clubs for the aged.

It is said one cannot eat, talk or sit down until he establishes his place within each new relationship. There are alone 200 forms of the pronoun “you,” from “most honorable” on down. That accounts for the ubiquitous exchange of business cards and obsequities. It’s a learning process from babyhood when mother forces the child’s head downward in greeting to father.

In adulthood, traffic is ignored as the boss drives or walks by and one stops to make proper obeisance. The wife is not exempted from the protocol as she rises and offers a subway seat to the boss’s wife standing nearby. One must be constantly on the alert for opportunities to be courteous.

It creates, said the wife of a Mid-West electronics executive, an “uptight society.” After living in Tokyo 18 months, she added, “It was fine, but you never know where you’re at. You have to be so careful with everyone.”

At that moment, prior to their departure for the U.S. from the Tokyo airport, she was surrounded by her husband’s employees and co-workers. One secretary held the baby, another kept inventory of parcels, a third got drinks. They were acting out their on, the sense of mutual obligation and responsibility, until the last moment. Once on is felt, it can go on forever like the Christmas card mailing list. Consequently, the Japanese takes on only as many as he can handle.

That excludes foreigners because offering them help could bring upon on. Some argue that is why social services are under developed in Japan, in particular for the elderly. Care is considered a family obligation. But few worry about what happens to the isolated or orphaned, indeed, those lacking on-ness with others.

The strongest sense of obligation is, of course, filial piety. A Japanese gets emotional about his indebtedness to parents and recent ancestors. He recalls his helplessness and dependency as a growing child and the “trouble” he had caused. The saying is that “only after a person is himself a parent does he know how much he owes his own parents.”

This is a sentiment the Japanese share with other Eastern and some Western societies and they decry the “minimal ties and feelings” of U.S. children toward their parents. To them, happiness is dependence. Security is acting by group consensus (at home or at work) rather than upon one’s own judgment. Individual decisions could lead to mistakes and a loss of face.

As a result, a simple request (from a Westerner’s point of view) becomes a group project. To find a translator for me one afternoon, six consultations, eight telephone calls and two days were required. To find a grandmother to visit, involved a professor of sociology, her seminar of 12 students, telephone calls to three families, discussions at the other end of the call and finally a request of the elderly woman herself. Without these preliminaries, she probably would not have consented. Contacts are more important than credentials.

Within this tight structure, surprises can be kept to a minimum and expectations exorcized. As one ages, fatalism checks appetites and one is geared to the non-pursuit of happiness.

“Buddhism,” said Shigeharo Matsumoto, 72, “teaches us to be fatalistic.

“We acknowledge four evils in life,” added the former Yale University scholar. “They are birth, ill health, old age and death. So we become resigned to these things and as we advance in years, we expect less in life.

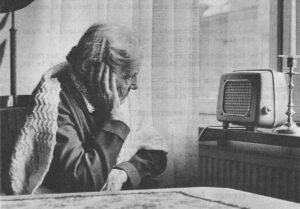

“By comparison,” said Dr, Matsumoto, “the American gears his whole life to the pursuit of’ happiness. But he does it independently. Then, when he is old, he is lonesome. If there is money, he may travel around the world. But the sense of independence dooms him to loneliness. It’s something you don’t think about when you are young and energetic, but when the energy fails, you become even mentally lonesome.”

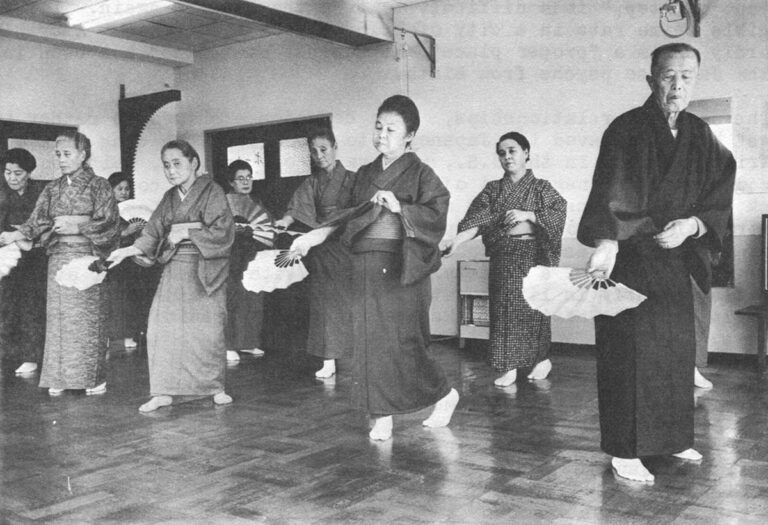

Interpersonal dependency, added the tall, muscular writer, as he puffed on a Dunhill pipe, are antidotes to loneliness in Japan. Indeed any reason is an excuse to form an organization, even an exercise and fan-dance club for the elderly. But the core is common interests rather than age. In the U.S., by comparison, age alone is the common denominator of Senior Citizen clubs, as they are called, and no thought is given to whether a retired lawyer wants to join a plumber at card games because both happen to be over 60.

Dr. Matsumoto, despite membership in the Yale Club, is proudest of the Shadow of Oak Leaves Club made up of fellow high school graduates. For over 55 years, they have continued to meet monthly for a curry-and-beer lunch. He admits, however, he hasn’t reverted to wearing a kimono or taking up Japanese pursuits of tea ceremony and poetry writing, as have his contemporaries. Because of’ his “American experience,” he said, he continues to wear the Ivy League “costume” of gray slacks and navy cashmere pullover sweater.

He is about to retire as director of the International house of Japan, a prestigious institution where international scholars may stay, do research or attend conferences. “It is necessary,” he said, “to vacate the post for a younger man. The mentality should change.” That the “younger man” is 65 is in the nature of things in Japan. The age difference between sempai or teacher and kohai or student/successor is sometimes only three to five years. A good manager, said Dr. Matsumoto, should make the gap as large as possible.

Sempai-kohai is part of that vertical social arrangement and exists at all levels of life. Invariably, the Westerner on business will confront the combination be it in politics, business, art or a village setting. The bond is as binding as that of husband and wife. It is the sempai who helps in selection of job and mate, attends the wedding and baptism and receives the most expensive New Year’s gift.

I saw sempai-kohai-ism in action one Sunday in Kyoto. A kohai (who happened to be a former member of parliament and a candidate for mayor of Kyoto) relinquished a day with his family because his sempai (a professor of sociology at the local Doshisha University) said I should be introduced to some villagers. (Both had also attended Harvard on special grants, the older man having paved the way for the younger.) The professor, to show his gratitude for the favor, in turn cancelled his plans and accompanied us into the countryside.

Once in the village, we met another team of two farmers. After touring, we settled down to lunch in the village hall. There, the sticky problem of protocol, with two obviously uneven sempais, was graciously resolved by seating me in the middle of the knee-high table and the professor, cattycorner.

Sempais are also essential for getting a second job, since the first ends at age 55. Some companies, like Sanyo Chemical, are extending retirement to 60 because of the labor shortage, but few are following suit.

About 70 per cent of the aged, meaning those 55 and over, are forced to find new jobs because retirement funds are nil. The infant Social Security system, introduced in 1963, offers about 15 dollars a month in benefits and excludes those who retired before that date. The few existing company pension plans offer, at best, only one-fourth of the pre-retirement wage. With an annual inflation spiral of seven per cent, it is estimated that 400 dollars a month would be a realistic retirement minimum. Few achieve it. The one job most available to retirees is that of doorman, which may account for the thousands at each turn in Japan; it pays only 100 dollars a month. Those with army pensions can count on another 31 dollars in benefits.

Toshio Fujisawa, 56, considers himself lucky in starting a second career as personnel manager of a small, modern Kyoto hotel. Until his retirement last year, he had been chief of cultural activities for the Kyoto department of tourism and earned 375 dollars a month. Now he settles for about half that amount, plus a civil service pension of 124 dollars and army benefits. He has a daughter in college and a wife to support and would prefer not to rely on three married sons for help.

![Mr. Fujisawa talked about John Wayne and "old soldiers [who] disappear."](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Japan_Skerly05-768x1171.jpg)

“My son could get me work in his kimono-slipper business,” said the well-dressed, Jerry Lewis look-alike. “But I don’t want to trouble him. If I need more work, my friends will help me.”

Friends translates sempai. One in the Lions Club got him the hotel post. In turn, Mr. Fujisawa feels obliged to keep an eye out for his brood of kohais, who take him out for drinks several times a month.

“It is difficult,” said the affable, well-dressed administrator, “to change positions if you have no connections.” He also criticized the absence of health insurance and pension schemes in post-retirement second jobs. Given a choice, he would have preferred quitting the first one at 50 so he could still qualify for a well-paying one with fringe benefits. “But advancing retirement to 60,” said Mr. Fujisawa, “puts too much responsibility on the aging man aid prevents the young from going up.”

His retirement was celebrated with eight parties, all given by kohais (never the employer). His popularity is not surprising. Even through a translator, his good humor, punctuated by jokes and much laughter, gets across.

But when he wants to be serious and underscore a point, as when asked if he misses his old job, the former World War II private presses his palms together and bounces them off each knee.

“Yellow ribbon,” he said suddenly, as his face grew wistful. “Yellow ribbon and John Wayne. That’s how I felt. Like John Wayne who commanded the calvary and then had to retire. Suddenly he lost his commandship.

“No,” he added with a grin. “I don’t resent it. I took it for granted that I would retire at 55 so I expected it.” Then, throwing in another famous reference for good measure, Mr. Fujisawa quipped, “The only thing an old soldier can do is disappear (sic).”

Socially, he has not departed the scene at all. Between the O.B. parties (meaning old boy) with fellow retirees and his drink dates with kohais, the calendar is full. At New Year’s time, he added, subordinates inundate him with about 60 gifts of shirts, oranges, whiskey and green tea. (Of course he must eventually repay the gesture. Japanese etiquette decrees that each present be repaid with a more generous one.)

Little is said about Mrs. Fujisawa. Except for the occasional trips they take together, she apparently stays at home as is the norm, while he goes out with the boys. Traditionally, the Japanese do not entertain in the home and it remains the man’s private castle. In it, when he arrives, he is ichiban or number one and the wife awaits him with slippers, kimono, hot tea and a hot bath. It’s a system, which has wooed and won over many an American male.

To become ichiban at work requires little more than perseverance. Rank and salary are based upon age and seniority rather than ability. Aggressiveness is frowned upon and one must await periodic promotion along with others who joined the company when he did. The less competent get empty titles like Lord of the Shop or Living Dictionary of the Office and the top brass are weeded out as consultants.

Life employment with one company is the rule rather than the exception and the employer provides what anthropologist Chie Nikane of Tokyo calls the “new familialism.” That includes housing, schools, discount shops, vacation areas, and for some, golf and other club memberships, expense accounts and chauffeured limousines.

Employment with one of the older, established companies guarantees instant credit, or the reverse if one attempts to leave it. Other employers wonder what’s wrong with the job shopper since it’s impossible to get fired. Even university demonstrators, whom Richard Halloran of The New York Times dismisses as “participating in political and intellectual panty raids,” settle down by the senior year and start interviewing companies.

The obvious disadvantage of this all-encompassing paternalism is that it stops when the job does. A man retired in his mid-fifties is suddenly faced with a drastically reduced income and without a (company) roof over his head. In Tokyo, after he leaves the 10 dollar-a-month subsidized rental, one alternative is a “one DK” (meaning one bedroom, dining room, kitchen) at 62 dollars a month.

Newer dwellings are so tiny that children sleep in hammocks slung over their parent’s bedstead. Thus, moving in with adult children is rarely feasible. Buying a house is also out of the question except for the very rich. A modest-size bungalow in Tokyo sells for 63,000 dollars. Because of the housing squeeze, nubile maidens a few years ago were told: “With a house, with a car, without an old lady.”

A monthly influx into the capital of 3,000 persons further exacerbates problems of living space, inflation, medical care services and hygiene. Only one-third of the city is equipped with sewers.

Demographers estimate that 70 per cent of the elderly manage to live with their children, but in less than ideal conditions. About three million families need housing.

Although only seven per cent of the population is over age 65, proportionately there are more very old and also infirm persons. The life span zoomed from a pre-war rate of 46.9 to 69.3 years for men (surpassing the current U.S. statistic); and from 49.6 to 74.7 years for women.

The government merely collects the data; say critics, and does nothing about providing needed services. Three times more is spent on economic development than on social welfare.

In an editorial, the Tokyo daily, Yomiuri, castigated the government, “which has ignored or shirked its duty to the nation’s senior citizen.” It has failed to provide free medical care to those under age 75 or to provide adequate pensions, the newspaper added. Reportedly, 600,000 older persons live alone, 400,000 are bedridden, 86,000 are without care and a further 170,000 cannot afford more than two meals a day.

“We have modernized in one century,” said Yomiuri, “but at the sacrifice of the environment and of our needy and handicapped.”

“It’s a poor attitude,” said Kazuko Tsurumi, professor of sociology at Sofia University. “Once a year in September there is a lot of fanfare about Rojin Nohi or Day of the Aged. The government distributes checks and certificates then it’s all forgotten for another year. We do the same thing about Hiroshima.” The comely educator, an elegant, kimono-clad lady in her fifties, could have been talking about the U.S. as well. We have created Senior Citizens Month in May, promoting aging as we do Pickle Week, Mother’s Day and the cake bake-offs. Politicians doff their hats to bingo players and senile centenarians, and, in election years eulogize those “worthy Older Americans.” And that takes care of the matter until the next time around.

Right now, Miss Tsurumi could use some home-aide services at a reasonable cost. (So could many working adults in the U.S. saddled with bedridden parents.) Most of her salary for the last seven years has gone toward nursing services for her aged, homebound father who lives with her.

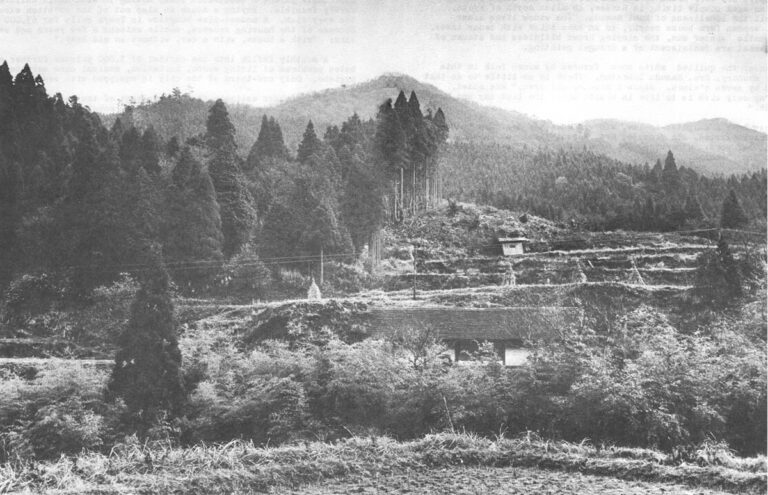

Life tends to be more gentle in the rural areas of any country. At least neighbors are more aware of one another. But the companionship of the Hosos, an aged couple living in Hanase, 18 miles north of Kyoto, doesn’t quell the loneliness of Humi Masuda. The widow lives alone in a small, wooden farmhouse nearby, in an area thick with cedar trees. Under the gentle winter sun, the sloping brown hillsides and stacks of honey-hued wheat are reminiscent of a Breugel painting.

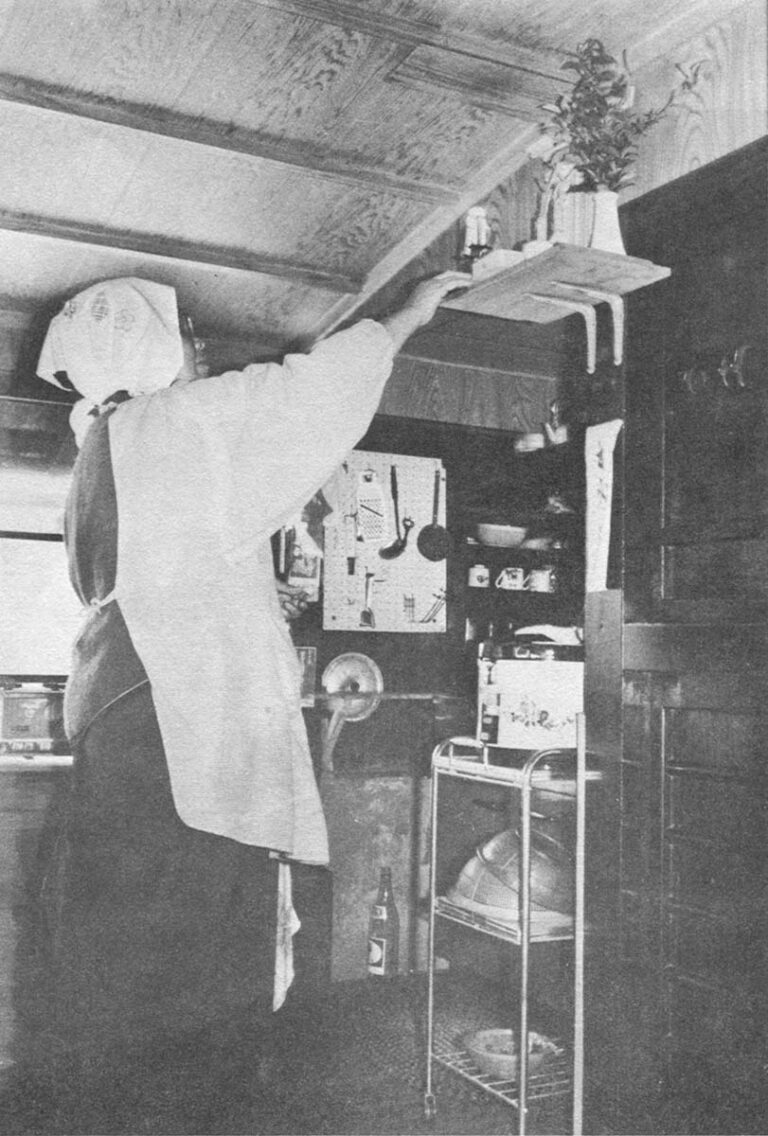

From under the quilted white hood favored by women folk in this part of the country, Mrs. Masuda lamented. There is so little to do that I am in bed by seven o’clock. Since I have no children,” she added, solemnly, “my only wish is to live in health until the last day and have a sudden death.”

She does have a daughter-in-law, widowed when her son died in the war. When the girl remarried, she promised Mrs. Masuda financial support and she has kept her word. Otherwise, the aged woman would be strapped with a miniscule army pension.

The gesture of help is not an unusual one. Although children have moved to the cities, leaving their elderly parents behind, ties are merely strained rather than broken. In one form or another, they tend to be conscientious about their obligations.

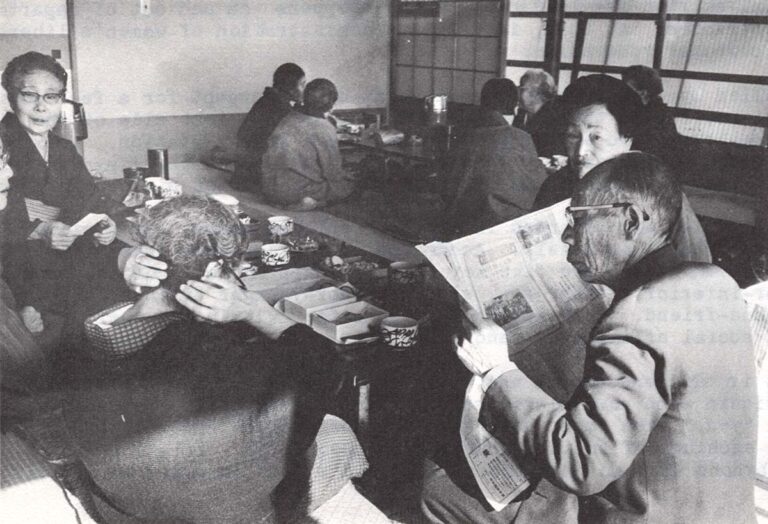

We sat in the spacious, modern Hoso farmhouse, huddled around a knee-high, square table, dangling stocking feet over hot charcoals gleaming in the ground below. The brazier is the main source of heat in Japanese homes, usually fed by electricity in the cities.

This one also solved the omnipresent concerns about etiquette. It was a damp, chilly day and everyone quickly shed shoes at the door stoop and scrambled inside to find a warm place under the table. In the rush, the demands of proper place were temporarily forgotten.

Hanase Hoso, 72, bustled to serve ceramic thimbles of hot, green tea. Also yokan, a prized, sugary sweet made of jellied kidney beans. It looked like pale, chocolate fudge and there the comparison ended. She smiled through gold and stainless steel teeth and beamed as visitors praised modern household appointments. There was that incongruous (to me) mixture: Kojin, the fire god in a niche over the electric rice cooker, a telephone, Buddhist shrine for ancestor worship, the charcoal brazier, another mini version for toasting hands and two television sets, including a portable in color.

Our host, Tasaburo Hoso, a retired lumber broker, wore beige, wide-wale corduroy knickers with a cardigan sweater in matching tone. His wife, a robust, rose-cheeked woman with an energetic manner, reminded me of a Norwegian fisherwoman – except for the bulky, wool britches she wore under the tunic apron.

Mr. Hoso looked around at paneled room and shrugged. Modern amenitities, he explained through the interpreter, were a poor trade-off for quality of life, as he knew it in the old days.

Now 75, he recalled walking to Kyoto. That pleasure has given way to smelly, motorized traffic. Where is the romance he asked rhetorically. He misses making charcoal at home and using horses and steam to transport logs. “Life used to be cheaper,” he added. “But at least the water here is not yet polluted.”

The farmer’s eyes gleamed as he spoke of good trout fishing in local streams. With a grin, he pointed to fishing poles suspended on beams overhead. He also looks for unusual pieces of driftwood and positions them like sculpture around the living room. In winter, he cultivates vegetables and recently added bonsai dwarf trees to his horticulture hobbies.

A daughter lives nearby. And six other children, dispersed to the cities, contribute to expenses. “But good health is the most important thing,” said the wiry, white-haired farmer. “Even a fortune is useless if you lose your health.”

The Japanese is preoccupied with both health and nature. He gives his body the same meticulous care he does his garden. The ritual of hot baths and exercise is only a part of the former. “He identifies with nature so completely,” said a long-time American resident in Tokyo, “that he does not fear death. The aged fear separation, but not death itself. He accepts it because he feels he is born from nature and going back to it. It’s a matter of waiting for someone from the other world to come and take him. Thus they are as linked to nature – a part of the chain – as they are to each other.”

Nature worship runs the gamut from Ikebana floral arrangements at each family shrine to spending a holiday in Kyoto called The Viewing of Tinted Leaves. Formal gardens, crafts and art forms, food preparation, kimono prints – all point up the love affair with nature.

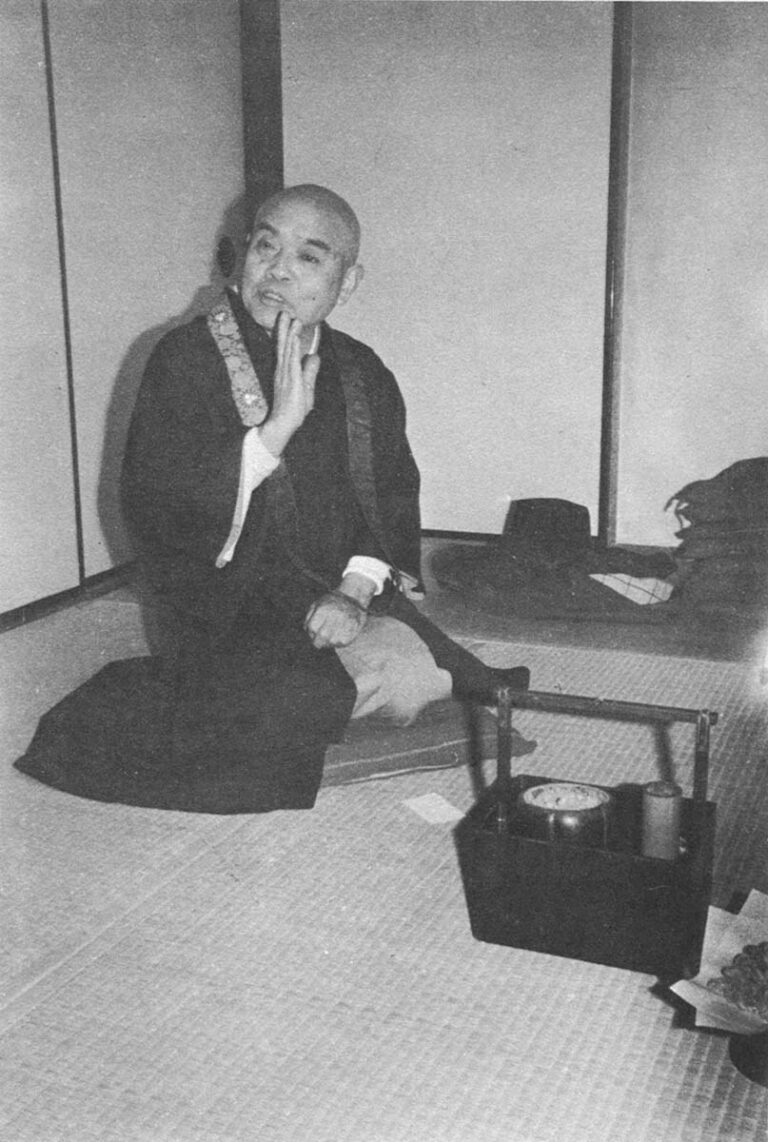

For some like Jakuyu Yasui, 68, it becomes a lifetime calling. As a youth, he inherited the 300-yearold family shrine and continues to manicure the huge, temple garden daily. He is a Buddhist priest and father of four. “I spend my days,” said the poised, balding man, “praising Buddha, cleaning the garden and counseling worshippers over tea or wine.” Throughout our conversation, he sat on his heels, knees folded before him, in classic meditative pose. The thin slivers of wooden paneling and parchment-faced sliding doors offered little protection from the cold. There was some warmth from a small electric heater, more from tumblers of hot, pale green tea he continuously served us.

A son, currently studying art, would some day succeed him. Despite a decrease in the number of worshippers, there was no question of closing the temple or the gardens. The latter creates the essential ambiance for worship and the Yasui son is learning the basic principles of landscaping.

Craftsmanship in any chosen field for that matter is revered. There are so-called masters and their disciples in gardening, flower arranging, the tea ceremony, theater, painting, ceramics, etc. Names are bequeathed as well as titles. Hence, a Joe Smith, judged equal to, say, a Rembrandt in painting skills, becomes Rembrandt the 14th or whatever the generation.

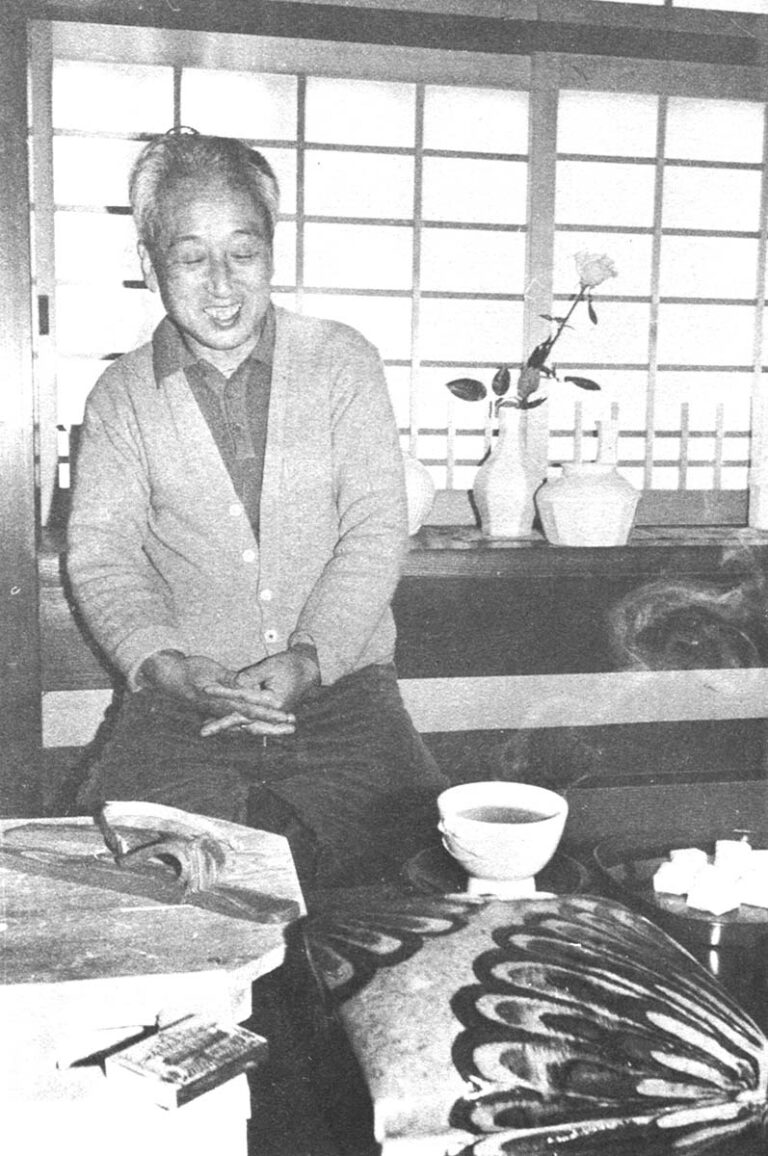

Artisans rarely think of retiring, Tsuguji Ueda, 60, a master potter from Kyoto, said, “You do this kind of work until one minute before you go to heaven.” He added the routine postscript: “Of course, it depends on your health.”

There was no question about his own as he tugged at heavy clumps of wet clay to show how he formed the large, marble cake patterned bowls. Their average selling price is 250 dollars. An assistant will probably inherit the business since there are no offspring.

And someday, Mr. Ueda may receive that highest of accolades, the designation as Human National Treasure. There are to date about 70 such living treasures roaming about Japan. They get a government decoration and a lifetime stipend of about 1000 to 1500 dollars a year. Over three-fourths of the recipients are over age 70.

The award was first bestowed in 1955, as part of the cultural properties law. It’s official purpose was “to preserve cultural properties of’ high historical, artistic and academic value and ensure their proper use /for/ the cultural advance of the Japanese people…”

Those who work in arts, crafts or architecture are called “important tangible cultural properties;” and those in theater, music and industrial art, “important intangible cultural properties.” The newly appointed “properties” include a puppet theatre balladeer, a Japanese fue flutist, an obi weaver and a sword smith.

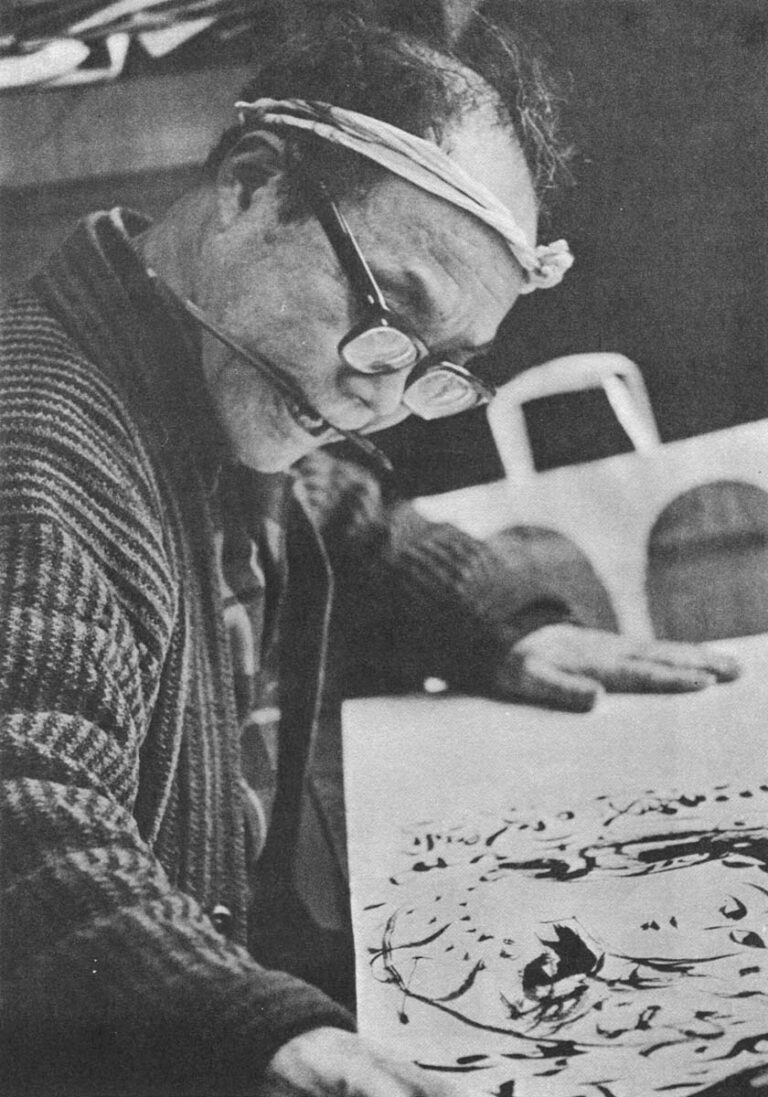

Others choose crafts as vocations because there is no arbitrary retirement age. Miss Truko Hashimoto, 53, began finger weaving, a method, which requires nails for the weft to assure a tighter pattern with gold and silver threads, about 10 years ago. Before that, she had worked in a factory. “I chose this,” she explained, shyly, through an interpreter, “because it offers the longest employment and I wish to work as long as I can.”

Her co-worker at the Tatsumura silk mills in Kyoto, Sunatoro Inui, never knew another kind of work. Now 65, he has been a weaver of brocade obis (the embroidered or woven type of “pillow” affixed behind a traditional kimono) for over 40 years. “The tradition has been in my family,” he said, with a timid smile, “and I will work until I can no longer see.” He earns about 312 dollars a month. One finished obi may cost many times that.

A craft may also be enjoyed for its own sake. At some point in middle age, both men and women begin to cultivate a cultural pursuit and allow it to absorb them into old age. Since the Japanese value system does not measure a man’s, worth by his productivity, he is free to express himself in any way he pleases.

It is said that once over age 60, the Japanese is allowed the marvelous freedoms he experienced as a child. Of course the outlets differ. Now he may decide to study philosophy with a Zen master or become adroit at the tea ceremony. The latter consists of learning elaborate, slow, dance-like movements for preparing and serving powdered green tea. The practice is a centuries old Chinese import favored by Buddhist monks as a physical discipline for mastering meditation.

(An organizer for a U.S.-type senior citizen club, confronted with such individuals, seemingly doing nothing, might feel uncomfortable. Back in Iowa or New York, she would probably force the mediator into a pinochle game, so he would be doing something, and the tea man into making potholders or a birdhouse, into doing something useful. In the U.S., there is a fear that older people who want to sit back and just daydream are in a state of withdrawal and apparently it’s psychologically unhealthy to sometimes do nothing.)

Some older Japanese have managed to turn hobbies into profit. In Kameoka, center of silk brocade factories outside Kyoto, Suka Nakatauka, 61, grew strawberries and chrysanthemums as a sideline to rice farming. When the growing affluence in Kyoto provided a market, they became major crops along with the raising of 45 Kobe-beef type cattle. They are considered the king of sirloin on Japanese and overseas tables and fed on beer. Each is worth 4,000 dollars. The tall, robust, jolly-faced grandmother of three looked like an overweight Myrna Loy. Her casual dress of quilted overalls and a jacket belied her obvious wealth.

The money, a source of confidence for many persons, seemed to make her more outspoken than other, older Japanese women. Especially on the subject of youth. “There is this democratic tendency to let young people do as they wish,” she said. “But that does not bring peace into the family.” One had the feeling that she kept her own three adult children in tight control, via purse strings for one thing.

Mrs. Haruyo Fukuhara, a retired teacher, who was educated in a Nashville bible school and now worked as an interpreter, was part of the group sitting around the brazier of hostess Tuneko Ishino. As we sipped tea and munched rojan, Mrs. Fukuhara said young people “sway to the extreme. They seek an independent life. To farm, however, there is a need to work together, to plant and harvest and then share in the profits.”

Mrs. Ishino said nothing and preferred another sweet. A widow since her daughter was five, she resolved the problem of keeping her rice farm going by adopting her son-in-law. The condition is an acceptable one where there are no male heirs. He relinquished a job in the city in order to marry the daughter and inherit the property.

Another neighbor, Masaichi Nakazawa, 65, solved the problem of keeping three sons on the farm by switching from rice to chickens. The youthful-looking entrepreneur, a Japanese version of Colonel Sanders, the Kentucky fried chicken magnate, raises 40,000 broilers, 30,000 egg chickens and has 38 employees.

Five stores of the take-out variety retail the products. They include dishes like chicken tempura, batter-coated pieces of chicken that are deep-fried and sold hot or frozen for home re-heating.

One Nakazawa son now heads the business, another is sales manager and the third manages the outlets.

“I originally wanted to teach, not farm,” said the father. “But when I inherited the farm as the oldest son, I studied agriculture and decided to become the best rice farmer in Japan.” Having achieved that, he served for 16 years as the equivalent of a cooperative extension expert and shared his expertise with local farmers. However, profits on his own venture were small and after the war he tried chicken farming. Row, as a third career, he is vice mayor of the community and wants to do more in civic service. “That is what keeps me young,” he said. “I am continually exchanging ideas with younger people.”

So it continues. With more examples of healthy, active Japanese coping with aging, or seeming to, both in urban and rural settings. They seem to tap a limitless fount of flexibility and tolerance.

Given the automatic benefits of filial piety to fall back upon, it seems all too liberal to hear a grandmother say, “When democracy was imported at war’s end, all men were equal. So the old must respect the young and follow them. Mutual respect is the most important thing. If my children want to go out for the evening, I give them precedence. If the old complain, they will be disliked. Staying at home used to mean good virtue, but times have changed.”

The words are there but are they backed by conviction? Dr. Takeo Doi, a Tokyo psychiatrist defines it as “the capacity to accept duality of values and the ability to compromise.

“The aged,” he added, “try to compromise with the young. But underneath they are resentful. The number of aged suicides is increasing because they feel lonely and neglected and a decline in prestige.

“We pride ourselves on being advanced industrially,” said the U.S.-educated physician and teacher, as we sat in his office along with his kohai, a fellow psychiatrist. “But our emotions are not western.”

To stress the complex nature of life there, he told about typical behavior of Japanese representatives to an international conference of the World Health Organization. “Others were noisy and telling about [psychiatric] developments in their respective countries. We were silent, not wishing to argue and reluctant to talk about our own traditions. Some feel we have none because of influences after the war or deny them. We are standing in the middle and trying to make a bridge between the past and the present.”

Received in New York on July 25, 1972.

©1972 Nada Skerly

Nada Skerly is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. This article may be published with credit to Miss Skerly, The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star, and The Alicia Patterson Fund.