It is known as the land of momism. As the home of Oedipus, the sacrificing mamma and the brooding mother hen. One talks of a cocoon of maternal over protectiveness. Simply said, Italy is “la mamma.” Whether she is 45 or 70, the mother commands Madonna-like adoration.

In fact, complains Corriere della Serra, the Milan daily, there is too much mamma. That’s why, it moaned in a classic editorial, Italy scored so poorly in the last Olympics. Mamma tells her son not to practice so hard or he’ll sweat and catch cold; to stay at home and take it easy. And down goes another would-be gold medal winner.

In fact, complains Corriere della Serra, the Milan daily, there is too much mamma. That’s why, it moaned in a classic editorial, Italy scored so poorly in the last Olympics. Mamma tells her son not to practice so hard or he’ll sweat and catch cold; to stay at home and take it easy. And down goes another would-be gold medal winner.

In the rural and tradition-bound south, mother and honor vie for first place in men’s hearts, with almost oriental intensity. Children and wife come after. Middle-aged men hail each other at the piazza bar or tavern with “How’s mamma?” (accent on the first “a”).

The northern, more westernized and temperamentally cooler son may be less demonstrative. Mother stands about fourth after job, wife and children. But conscience tugs. Also an emotional tie, a kind of spiritual umbilical cord.

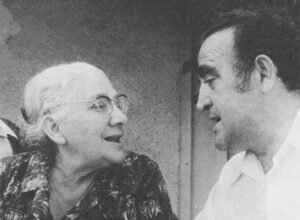

Ivo Coccodrilli, 28, a Milan businessman, said, “A strong and affectionate bond develops because mother is with you every moment of the day. With father, there is less contact.

“We don’t have the tradition of the working mother,” he added. “We like her to stay at home. Although that is changing now, she continues to hang, onto the child and is almost schizophrenic about doing both jobs well. She rarely allows anyone other than her own mother or sister to care for the child.”

The maternal clutch lasts through puberty, according to A.L. Maraspini, a sociologist. In his book, “The Study of an Italian Village,” he described the Italian mother as playing the part of the “guardian angel,” while papa (accent on last “a”) is cast as the feared paterfamilias, the “superior court of appeal” one must respect and obey.

He may have the last word, said the author, but the mother is a tyrant with insidious emotional power. “Her final resort is an appeal to the child’s love, which makes him far more helpless to resist than his father’s blunt and indisputable order.”

Few rebel against mamma.

As a woman, added Maraspini, she may be officially subordinate to her husband, but “as a mother, she enjoys…an exalted position…[that] her husband for all his legal and social power can never have.”

The childhood habit of dependency persists through adulthood. For a boy, mamma remains the dominant influence on his life. (Papa has to resort to financial or psychological ploys to maintain control of his grown children.)

Guiseppe first discusses a prospective wife with mamma. If she objectively sees no future in the match, she is usually right. If there is a subsequent separation or divorce, of course ore returns to mamma.

When short of cash or courage, Angelo turns to mamma. Petro abandoned a beloved, plus a brilliant engineering career in Toronto because mamma wanted him home and he “couldn’t hurt her feelings.”

Martuleo, a diplomat in Bonn, sits home each evening of his vacation leave, although his fiancée lives nearby, because “it gives mamma pleasure.”

The ultimate victim of filial piety was a Sicilian murderer who evaded police for months until that fateful day when he “had to go home to see mamma.”

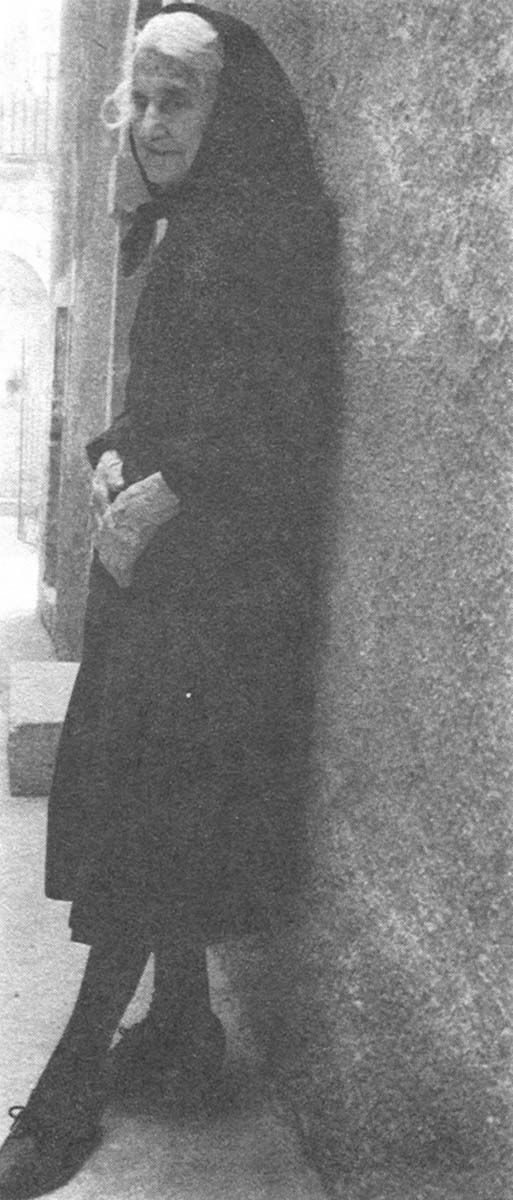

La mamma, especially when aged, expects all the bonuses of motherhood and usually gets them. In Scandinavia, the Volkswagen may be too small to take grandmother for a Sunday outing. But in Italy, her hulking, black-garbed figure is stolidly wedged into the front seat of the tiny Fiat, next to her son. The wife can sit in back or stay at home if she doesn’t like it.

Mrs. Coccodrilli carped that her three sons neglect to have her to dinner very often. But she makes sure of getting an invitation to spend Christmas or the August holidays at some spot. She dips into her modest widow’s pension for a new suit and accessories (de rigueur in fashion-conscious Italy) and lets them pay for the rest.

In production-oriented societies of the west, grandma often must justify her existence by being useful. She is expected to be at least a babysitter.

In Italy, if she lives with the family, as most still do, she earns her status simply by being. Again la mamma, or rather “nonna,” as she is called.

If she feels like helping out, she will; otherwise, not. There is none of the “babka” compulsion common to Eastern Europe and Russia. There, granny becomes an unsalaried and overworked household drudge and baby nurse.

When the Italian nonna helps to raise children, she takes over their eating and dressing needs until they are nine years old. A special closeness develops. A grandmother charmed by the cheeky remarks you made at age four, is a good pal to confide in at age 17 and beyond, noted one adult male.

“Sure it’s momism,” said Franco Ferrarotti, a Rome sociologist who divides his lecture time between the universities of Rome and Columbia in New York City. “But we never joke about it. La mamma is very important. Every Sunday you go to see mamma. We’re as clannish as the Jewish about it.”

Home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.

–Robert Frost

Mamma and the family, said Ferrarotti, represent security for the Italians, as the U.S. Government once did for Americans. (The church in Italy, he added, is diminishing as a source of values.)

“If you can’t face up to life,” he said, “you simply return home. The core value of society surfaced in September of 1943 when Italian soldiers deserted the fronten masse. Confused and seared, they went home. Something saves you all the time: The family.”

Italy possesses what the U.S. has lost, according to Charles Reich. In his treatise, The Greening of America, Reich lamented the:

“absence of community…modern living has obliterated place, locality, and neighborhood, and given us the anonymous separateness of our existence. The family, the most basic social system, has been ruthlessly stripped to its functional essentials…Protocol, competition, hostility, and fear have replaced the warmth of the circle of affection which might sustain man against a hostile universe.”

Perhaps the Italian family is too close, said Sarah Sergia, a native of Taormina, Sicily, and resident of Philadelphia for the past 26 years. She derided the “morbid mutual attachment of children and parents.”

But she’s part of the mold, too, said the chic and intelligent career woman as we sat in air-conditioned Rome-Taormina express train. She journeys home to Sicily often, with two handsome teenagers in tow. “They are all I live for,” she added. Her brother is the same. A postal official in Messina, he requested a job transfer to Rome so he and mamma could live with their university-bound son.

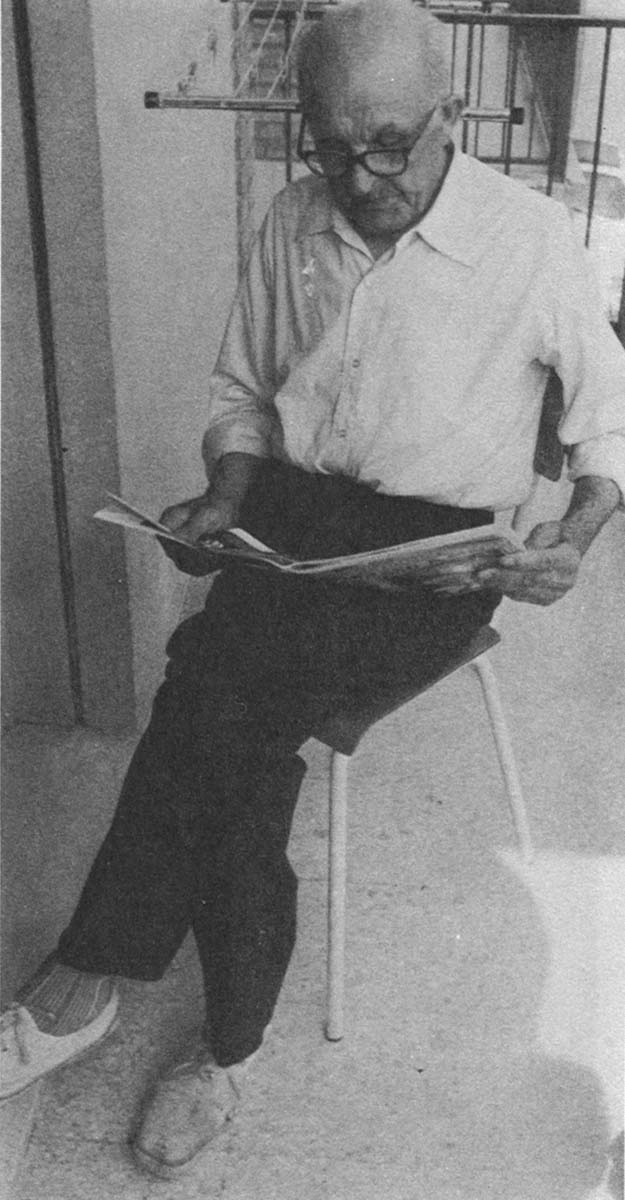

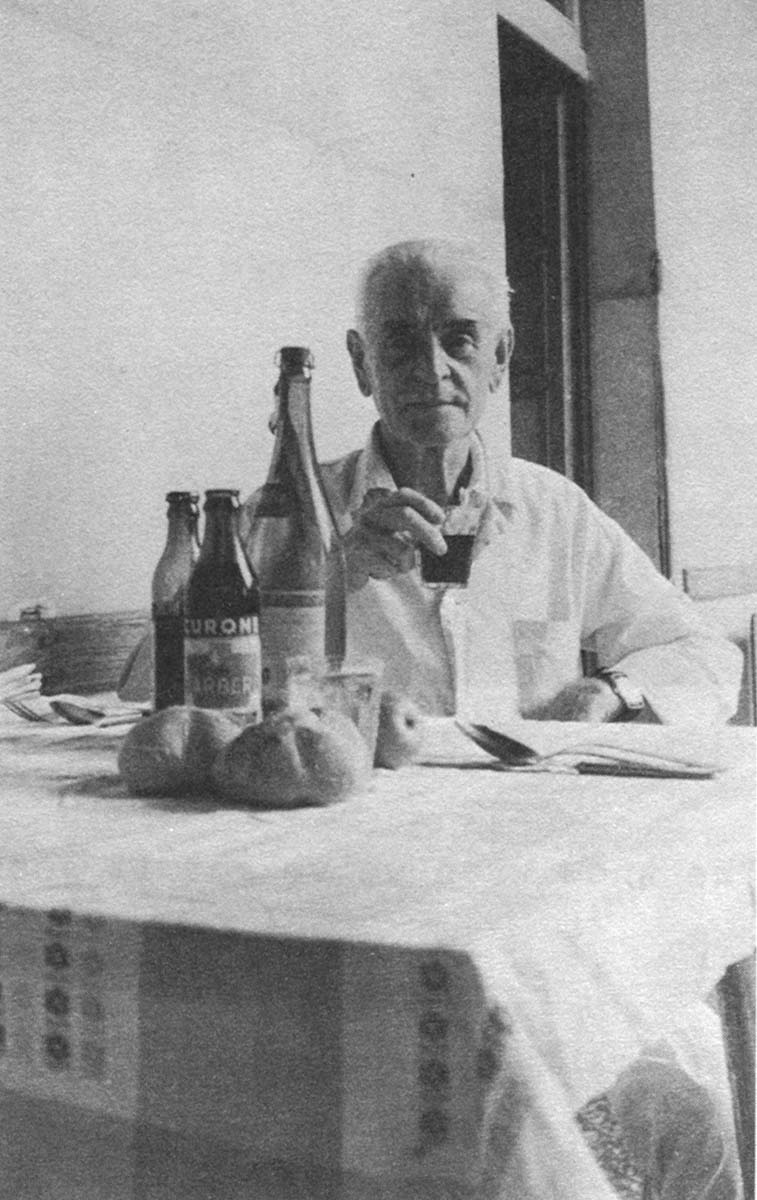

Dr. Mario Gagliardi described his biennial migration to the tiny mountain village of Malito as “an unconscious force similar to the return of birds back to the nest.

“This is my home,” said the ebullient 49-year-old general practioner. “More than in Union City, New Jersey.”

Gagliardi emigrated to the U.S. 19 years ago, married a first generation Italian-American of similar background, and adopted two children from Malito.

“Over there,” he said, “I have to right golf and baseball when I would rather sit with friends over a glass of wine. Here, I have time to do things like fix the shower.” He chuckled apologetically as he noticed he was still wearing the undershirt work clothes in which we had found him.

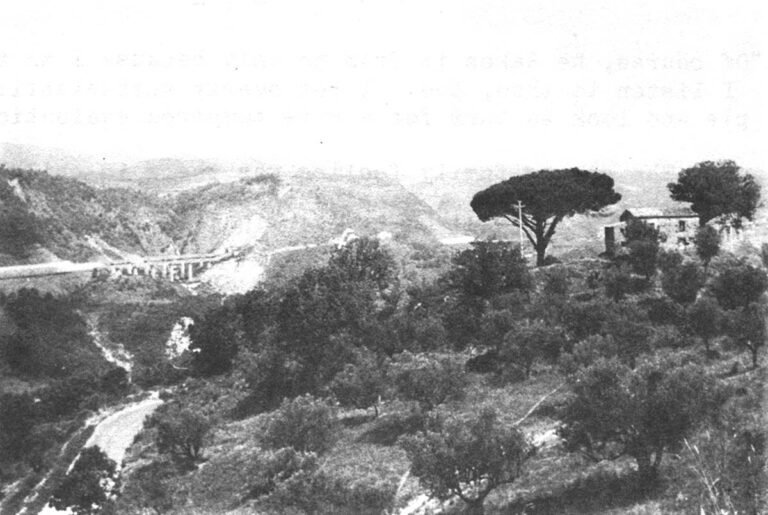

One doesn’t just run into folks from home within a walled community of 1200 persons, living 25,000 feet above sea level, and 25 miles from the nearest town of Cosenza. On the map, Malito is in the toe of the Italian ‘boot. (Near this historical area, are the birthplace of Horace, and the whirlpool of Charybdis, which menaced the ship of Ulysses.)

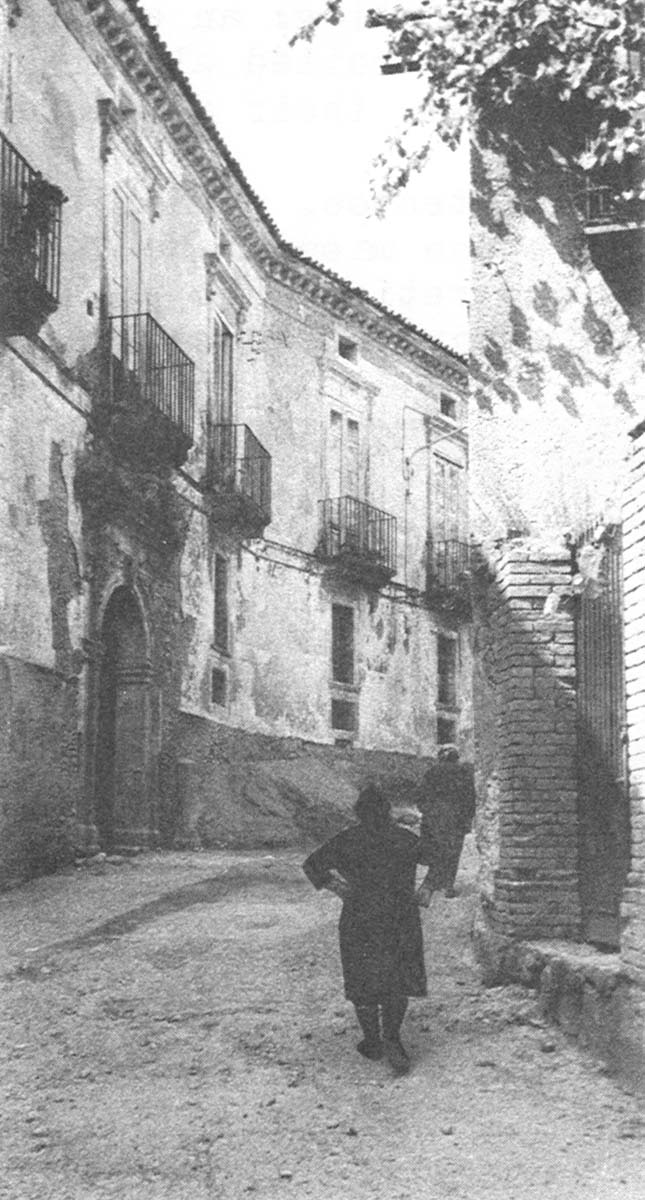

Streets are crevices between contiguous, high, winding, sand-colored facades. There is no audible or visible sign of the human dramas taking place within. The construction once afforded protection against medieval marauders; now, against nosey neighbors or foreigners. A few women in the ubiquitous black dress scurry about. Except for a bakery discovered by chance, there seem to be no stores, certainly no restaurants or an inn. Signs identify only a bar, tobacco shop, the mayor and carabinieri. Clearly one eats and sleeps at home and visitors are not encouraged.

With Gagliardi as guide, the atmosphere changed, but initially, he wasn’t even on the itinerary. With the help of an intrepid Italian professor of literature, I was seeking the parish priest for information on the “white widows,” another aspect of family life.

Padre was gone and so were my hopes when the professor shouted up to someone on the balcony of a house set apart from the others. It turned out to be Gagliardi, who motioned us into a rebuilt, well-appointed nine-bedroom house.

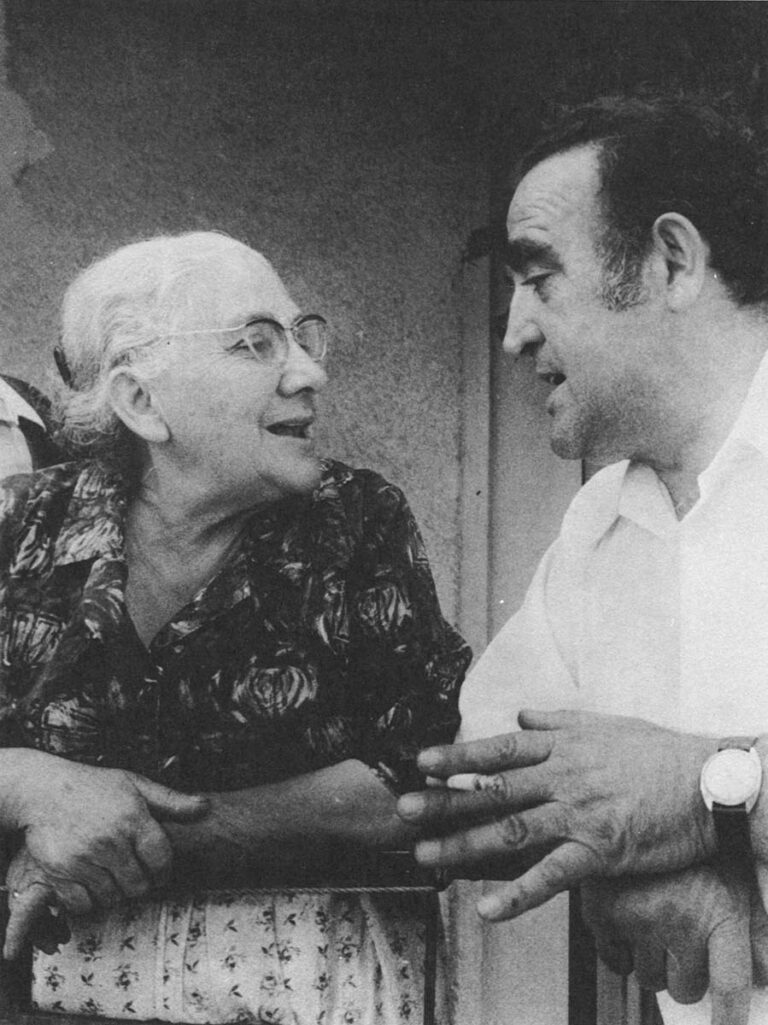

“You wanna speak English?” he grinned. His slightly accented, but effusive welcoming voice boomed, “Tell me what you want and I will help you.”

He promptly avowed, “My mother is sacred.”

Then, feigning displeasure, but relishing the recount, he added. “She treats me like a kid. She saves fava beans in the freezer because I like them and serves only to me the first wild mushrooms.

“She is proud of me,” he continued in more serious vein. “She thinks I’m a big professor over there. She gets lines of people ready for me here when I come. I have to do what she prepares for me,” he added good-naturedly, “all the incurables.”

The genial doctor excused himself and returned wearing a white sports shirt.

He was carrying a pitcher of Donnici, a full-bodied rosé of the region and some homemade salami. Rosetta, a sister and one of a dozen family members currently visiting, followed with a large platter of cured ham and pizza-sized mounds of village bread. (The hospitality continued into evening, and at parting, Mrs. Gagliardi proffered a gift of cake and wine, many hugs and an invitation to come again soon.)

“My mother dries her own prosciutto, even if she has arthritis,” said Gagliardi. “She knows the right combination of chestnut smoke and wind.”

He paused to toast wine glasses and added, “Who likes wine, likes people, remember that. And, call me Mario.”

He talked again of a mother who had thought of others first, herself last. One who “always had a kind word for father when things did not go well. She didn’t sleep when someone was sick, and was up two weeks after a difficult appendectomy. She is never tired and stands up for my brother (a divorced school teacher living at home). She waits up for us and is the last to go to bed, then the first up to make coffee.

“Even my wife had to understand that my mother holds a special place in my heart.” On the wall of the sitting room is a contemporary watercolor of Madonna and child. It was a Mother’s Day present from the grandchildren along with self-composed poems. Mario has written some too.

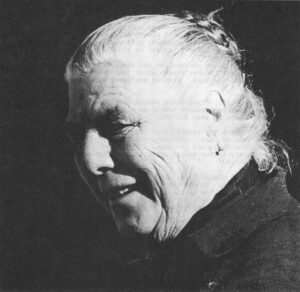

Mrs. Gagliardi, 73, entered and smiled her own brand of welcome. She spoke only Italian, but the benevolent, receptive face required no translation.

“The affection and pride I can see in her eyes,” said Mario. “She doesn’t mind my Calabrian irritability and bursts of temper. Searching for adequate praise, he lifted his arms up helplessly and said, “She is remarkable. She is more than that. She is the mother. I cannot say more than that.”

Mr. Gagliardi, also 73, popped in to say hello. Tall, handsome and muscular, he patted his son on the shoulder and teased him about not having shaved.

“But I chide him,” winked Mario, about smoking and overeating for his heart condition.

“Of course, he takes it from me only because I am a doctor,” he added. “But, I listen to them, too. I get overly enthusiastic about meeting new people and look to them for a more tempered evaluation.”

The secure family feeling was there in childhood as well. Mario’s warm, brown eyes grew pensive as he translated a poem he had written titled “Days without Worries”. In it he recalled chestnut and plum trees, crickets and frogs; grandmother plucking a rooster, and grandfather storytelling and sipping wine; falling asleep at dinner – “the moon a reminder that today would go and tomorrow would come.”

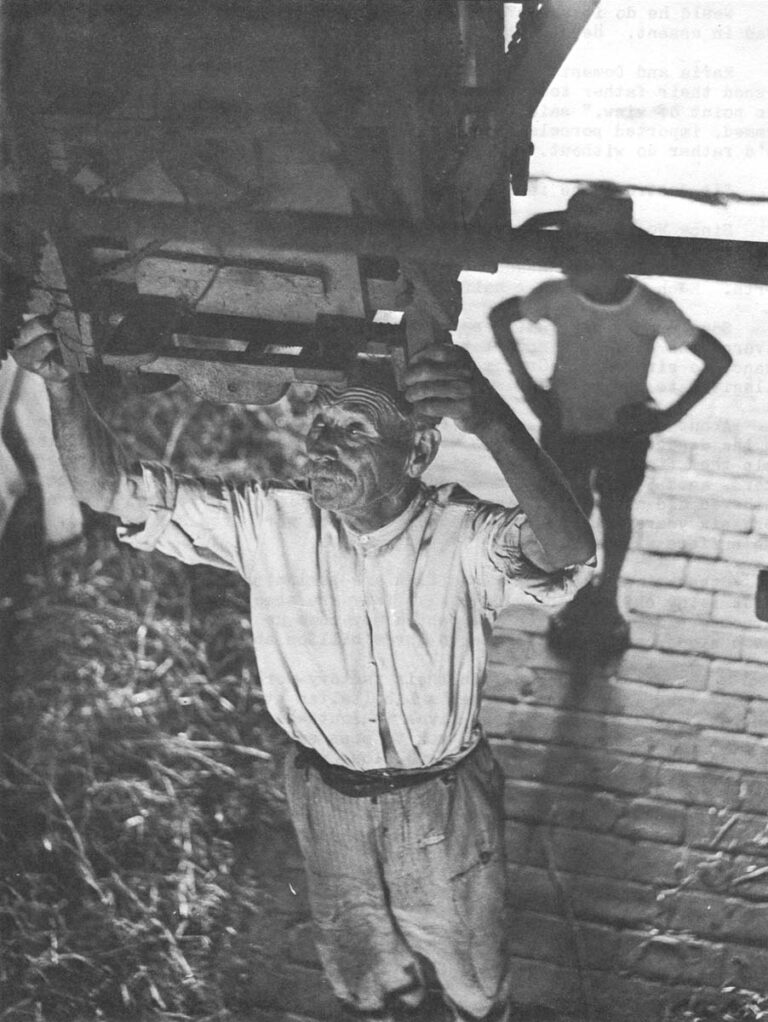

It was a tomorrow full of promise for the Gagliardis – made possible through the shrewd and enterprising senior Gagliardi. Other words, his peasant heritage and nine children would have doomed him to the poverty of his neighbors. He studied electricity through a correspondence course, built the first power stations and invested in lumber. Six of the nine children survived and are professionals with university degrees.

The search for the daily bread has whittled Malito’s population from 2000 to 1200 in the last 15 years. Most of the men immigrated to Canada, deserting the land, and often wives. Farming on the craggy slopes is limited to olives and grapes. Laborers far outnumber the few openings in forestry or road building. There is no government-sponsored development of local industry because of prohibitive transport costs. Hence, the insoluble problem.

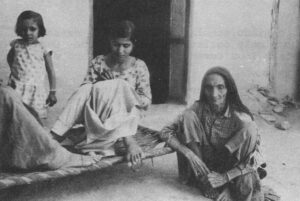

Only life continues: birth, pregnancies, premature aging; an existence devoid of all amenities. Dirty children in torn and soiled clothing play in dark and dingy entranceways. Depressed, you know their destinies.

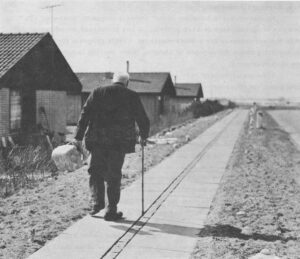

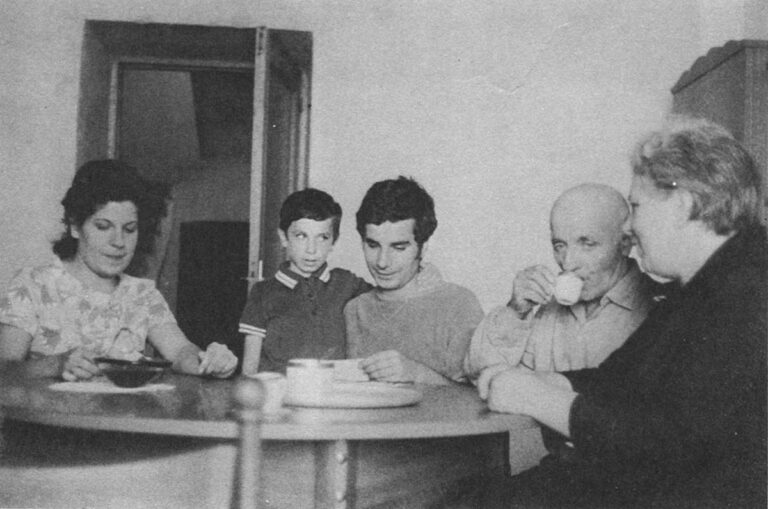

To change those of his three children, Guiseppe Potesteo, of Malito, went alone to Trail, British Columbia, to labor as a stonemason. He returned twice in 20 years for brief visits. Now 62 and retired, he points with pride to the fruits of his sacrifice: A newly renovated house and contemporary furniture; Maria, 25, a schoolteacher; and Domenic, 22, a physics major at the university. Pier-Guiseppe, 8, is bright-eyed, healthy and nicely dressed.

Over espresso coffee, one wondered why the elder Potesteo didn’t take the family along. Work was uncertain, he replied, shyly, and he had to move around a lot. He wanted to spare the family that.

Would he do it again? The slight, work-worn and bent man nodded his head in assent. He did it for the children, he added.

Maria and Domenic were critical of the long separation. They had missed their father too much. “It is understandable only from the economic point of view,” said Domenic. Maria gazed momentarily at the gold-rimmed, imported porcelain coffee service before us and added, flatly, “I’d rather do without.”

“It destroys the family,” noted Mario. “This is an exception.”

Since World War II, about 35 per cent of the population of southern Italy – over six million persons – has left for jobs overseas, or in Germany, Switzerland and Scandinavia, or in the industrial parts of the north. Each year another half million follow.

Some create new families in the foreign lands without bothering to divorce the old. A discount train fare at election times gives them a chance to sire more. Or sometimes, as a matter of honor, they adopt an illegitimate one born during the absence.

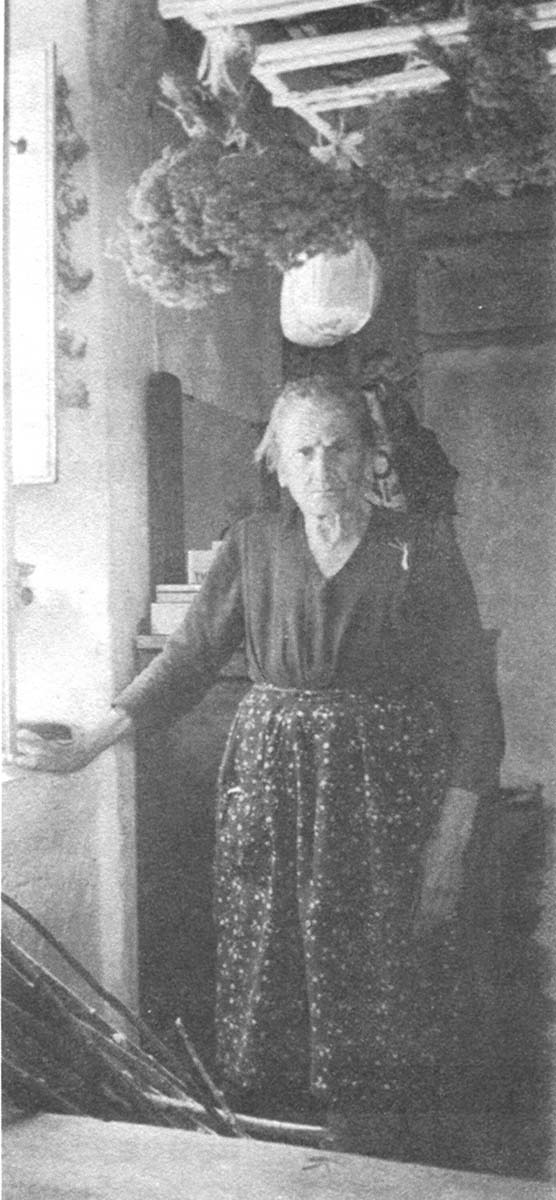

About one-third of Malito wives are “white widows,” a term applied to the deserted. Maria works with a national organization, which tries to help them financially. She got some scholarships for the eight youngsters, aged 5 to 19, of Gemma Vena. Mrs. Vena’s once beautiful face is withered and almost toothless, a chronic testimony to penury. For almost six years, she has had neither wage nor word from her husband. But she suffers silently.

The dusty, dirt road winds around mountains and olive trees into hidden feudal villages like Malito.

The young, have departed, leaving only the aged and children behind.

Grandfather and grandson at work. There’s no time for school.

Others less hemmed by tradition are beginning to grumble publicly about being childbearing chattels. They are also among the strongest supporters of the divorce law (which may come up for repeal). In the south alone, an estimated one to three million abortions occur each year.

Women who move north with their factory-worker mates are staging another sort of protest: Women’s Lib, Italian style. It’s against convention, not men. Harem-type lives in southern villages allow for one daily outdoor diversion: The trek to mass and back. La mamma is supposed to be church-house-family. Now, along with economic independence, she has social freedom.

All these displacements have naturally created problems for the aged. For grandparents left behind it’s an agonizing amputation. “At moments of emergency,” wrote Maraspini, “whatever its inner frictions and conflicts, the family becomes a compact unit and the departure of one of its members is felt as a wrench [akin to]…death.” Even a short hospital stay is considered tragic.

In 1957, the government was forced to allocate funds to families of émigrés to enable them to follow.

Not all do – as Calabrian villages inhabitated only by the elderly, testify.

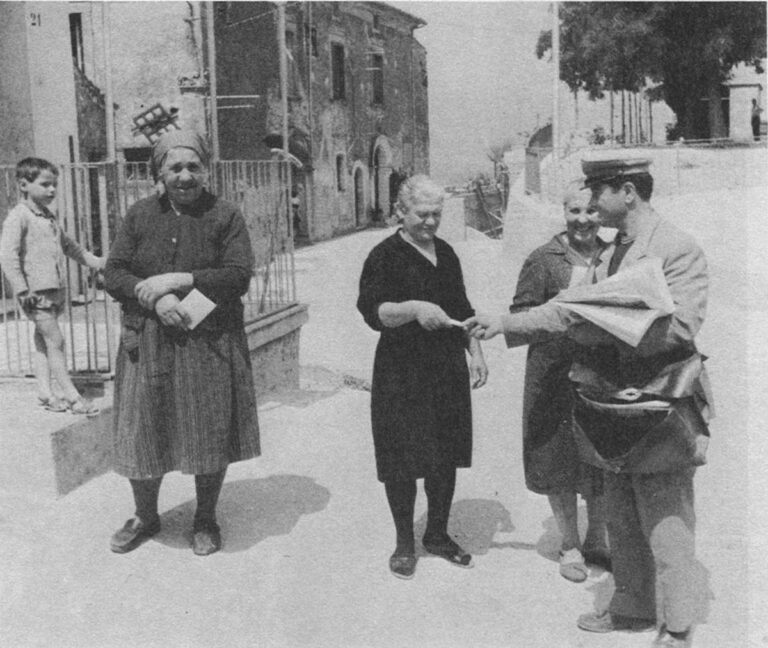

In the sun-filled People’s Square of Scigliano, population 5,000 (and a mountain away from Malito), Maria Pennesi, 61, awaits the postman. Four sons are working in Torino, and one grandson has remained behind with her. Maybe today there is a letter – and some money.

Others who follow their children to the north sometimes suffer a change in their status. Grandfather is no longer the autocratic “copoccia,” or household boss. Back in the village, land ownership and experience gave him certain leverage, certainly psychological.

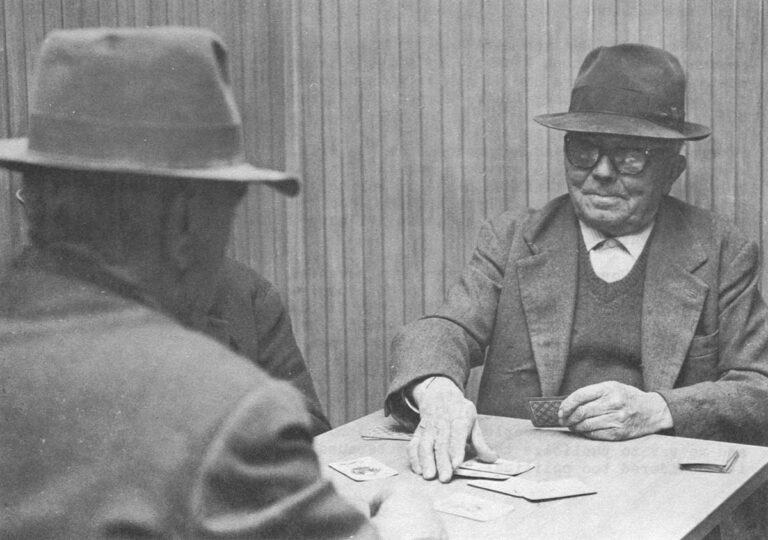

Then there were the “passegiatta”, the promenades around the square, and meetings with cronies to play cards or boccia (a bowling game). Or just to reminisce.

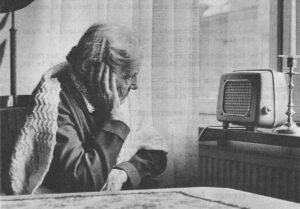

And mamma finds her son more emotionally independent as he becomes financially solvent. And she’s not quite sure how to manage within the four walls of the tiny flat. Things are different.

Pierino Solci, 84, and separated from big wife comes often to Lame, a worker’s suburb of Bologna. “Life is finished, life is boring,” he said with resignation. “There are few who think about us.” Without malice, he added, “I have modern daughters.”

It was Leda Rosa, a social worker, who revealed that none of the four contribute to his subsistence income of 20 dollars a month. That’s the minimum national retirement pension established this year by the government. Before this measure, 400,000 oldsters received nothing.

“That’s worth about three visits to the hairdresser,” said Miss Rosa acidly. “Nothing is being done for these people. There’s no budget, and no way to publicize their plight because it is considered too political.”

The Communist municipality of Bologna, considered the most efficient in Italy, established the Lame center as an experiment (two others are burgeoning in Prato near Florence, and in Bergamo). But the budget limits the health, housekeeping and social services provided, to only 15 persons.

Arnoldo Farina, representative of an international welfare organization, said it would be difficult to set up a similar Project in the south. “The problems are enclosed within the family,” he explained, and shame and pride impede accepting outside counsel. By the same token, it is considered a disgrace to send the aged to a home for the aged.”

In comparison, he added, northerners bunk their parents in hospitals over the weekend so they can go off on their own holidays.

“Not so,” said Dr. Francesco Antonini, a Florence geriatrician. (In questions about the aged, as in nearly every other aspect of Italian life, “northerners” disagree with “southerners.)”They pay me 40 dollars a visit to seek help, not hospitalization for their aging parents,” he added, in an emotion-charged voice.

There is too much invested, he said, to precipitate drastic changes. “We have been linked together as families for generations because of economic, religious, political and emotional reasons,” he said. “The son remembers his father made sacrifices so he might now enjoy an elevated status with cars and seaside villas. It is the upcoming generation which may have a shorter memory and make the break, and follow the trend of other industrialized European countries.”

Noted Dr. Gagliardi with unusual sarcasm, “We’re still 20 years behind in Italy. We still care for our aged at home. In the U.S., it has become convenient not to have them around. Affluence leads to egotism.”

And to a change of heart. After a tour of Copenhagen’s aseptic, modern suburbs, Italio Del Vecchio, a writer from Bari, Italy, expressed shock at the loneliness and isolation of the elderly. “No poor, Italian peasant,” he said, “would trade the warmth of his life for plumbing and some appliances. In Italy, the family still means something and the aged have a place.”

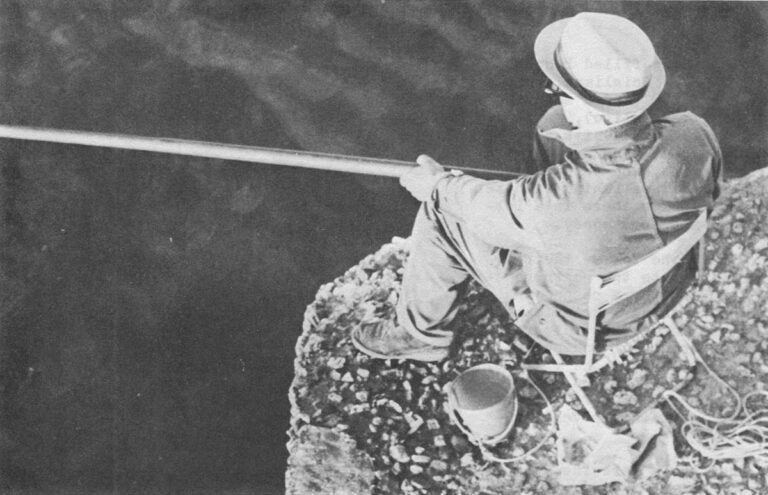

So many things to do in the country, that one doesn’t even think about them.

In the city, right, what is there left to do?

How much of one depends on who’s talking and from where – north or south. Along political lines, the Communists maintain the “bella familia” or beautiful family is fiction; the Catholic conservatives, that it is fact. These are the discrepancies of a diverse society facing the semi-problems of a semi-industrialized country.

For Ferrarotti, the sociologist, the family is “not disintegrating, but changing.” Especially the woman’s role. Angelo Del Boca, political editor of the socialist Il Giorno of Milan, said it is the only national symbol extant. “Mostly for economic reasons,” he added. “That’s all that’s left of the Fascist trinity of Country, God and Family.

“The country is now dead (because the advent of conscientious objectors will spell the end of the army). And the church has become a place to rendezvous.”

Luigi Barzini, who dissected his countrymen in The Italians, also finds, “The family is still the base of stability, even in a fluid and confused country like Italy. The wisdom of elders still counts and, in moments of stress, the Italians always behave as they did.”

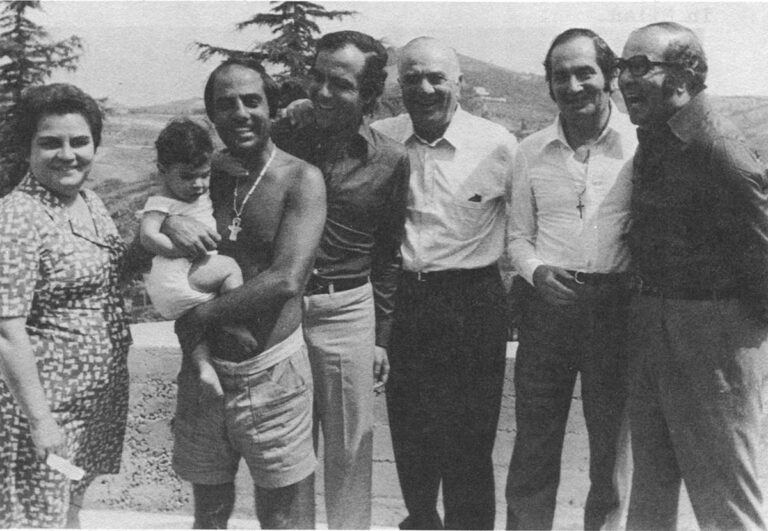

Even in moments of non-stress, they take certain things for granted. Papa’s name day is one of them. And if he happens to be a temperamentful, Neapolitan patriarch, like Carmine Pignataro, 75, the occasion takes on the dimensions of a birthday party, family reunion, and Fourth of July combined.

His American daughter-in-law married into the family a dozen years ago and still can’t get used to it.

“My family is close,” she said, “but nothing like this. When father Pignataro decide on something, his children drop everything and come running.”

He decided the “festa”, or feast, should be in Bologna at her house, a luxurious estate complete with swimming pool and dining table for 20. The figure, however, reached 50 at lunch for each of two days running.

Imported for the celebrations were card-playing comrades from Naples, business associates from 160 miles distant, and siblings from faraway Italian cities. It was a workday, but for father Pignataro, the business world stopped. Even the Bologna couple had to postpone their vacation in order to accommodate the brood. He had stated, “This year it will be in your house,” and that settled it.

As head of the family, he has the right to inquire into individual personal matters and to expect his counsel to he headed. In a crisis, a family council is held.

But this was festa time and one and all were welcome to the gala dinner held the final evening in a rustic, country inn. Even the chauffeur and a hairdresser papa Pignataro had met that day, were part of the 70 who turned out in Pierre Cardin suits and chic party gowns. Amidst much laughing, shouting, dancing and singing, until well into the morning, each kissed him on both cheeks (including the men as is Italian custom), and wished him luck. He was the last to leave, and as the last of the champagne was poured, he could indeed say goodbye to another “mia festa.”

Again in Rome, the joys of Adelaide and Guiseppe Morelli, septuagenarians, are bound up with those of their three children and grandchildren.

They live in the same apartment building as one daughter, see the other daily, and look forward to the weekly, Sunday, telephone call from a son in Milan.

Weekends they spend with either daughter at adjoining country houses outside Rome. No day goes by without a shared cup of coffee or a meal.

An American might resent so much togetherness as an invasion of privacy. But the thought never occurred to Marina Chianese, a daughter in her forties.

“We love each other,” she said. “And we enjoy being with one another, whether for gardening on weekends or just talking. My husband discusses his painting, with my father. There is always something to share.

“When we were young girls,” she explained, “we went out with friends. But when you are married, the feeling of family returns. Others may need to go outside the family; we do not.”

When Mrs. Morelli had three operations within a seven-month period, her girls attended her around the clock. She expected it, but added she would not burden them if chronically ill.

How did she manage such harmonious relationships with her children?

With a wise smile on her still lovely face, she replied, “I don’t interfere into their lives, and give counsel only if requested. I may have my thoughts about something, but I don’t say them.”

This is a lady who taught school at a time when career mothers were a rarity. About that, she said, “I don’t think a wife loves her husband less if she works.”

What was essential to life now? Without hesitation, Mr. Morelli answered, “Tranquility, health and reciprocal respect.”

The Morellis are economically independent and educated. Rosalia Caracciolo, a Milan-born widow, is neither. After her husband died, she waited 14 months for the initial factory pension check of 52.83 dollars. (There are 8.5 million aged in Italy out of a population of about 52 million. Three-fourths of them have retirement incomes ranging between 20 and 42 dollars a month.)

Fortunately, Mrs. Caracciolo had some savings, and a condominium arranged through her late husband’s employer. Some of her friends, by comparison, have been forced to share their children’s small city flats. “If I had to live elsewhere,” she said, “I would go to a home for the aged. I know my sons wouldn’t hear of it, but I would prefer to be on my own.”

It is for these persons, and there are many of them, that a few individuals are campaigning for a national policy for the “anziani,” or ancients as the aged are called.(Retirement is known as The Third Age.)

The embryo F.I.P., (Federation of Italian Pensioners), a labor union offshoot, recently met to chastise politicians for finding millions of lire to subsidize the “squalid” Italian movie industry, but none to extend health care to Pensioners. “With this kind of attitude,” said Mario della Forzinetti, F.I.P. secretary, “we cannot nourish excessive hopes for a national program for the aged.”

F.I.P. also wants repeal of a law, which discriminates against widows (who total half of the elderly population). If they were married less than two years to a man over 72 and were 20 years his junior, they forfeit pension rights.

Il Giorno has expressed concern about the abandoned aged or those without family or children. It cited needs for pensions, housing, home-aide services and nursing homes. The last were described as “cemetery waiting rooms”, where they go to die. “It that the prize society offers after so many years of work?”

A Catholic leftist youth organization in Novara, a suburb of Milan, decided it was not. Through public protest, it forced the local government to raze a 300-year-old depository for the elderly, as geriatric hospitals are designated here. But such manifestations are rare.

The Catholic Church is passive on the matter although it owns many such depositories.

In fact, the church has ignored the plight of the old although they make up most of its following. At best, it offers a “Dear Abby” type of letter forum in the slick church weekly called Famiglia Cristiana. A priest answers queries about dying hair, sex after 50 (he’s for it), and revived love after 80. The last, he claimed, is why women outlive men.

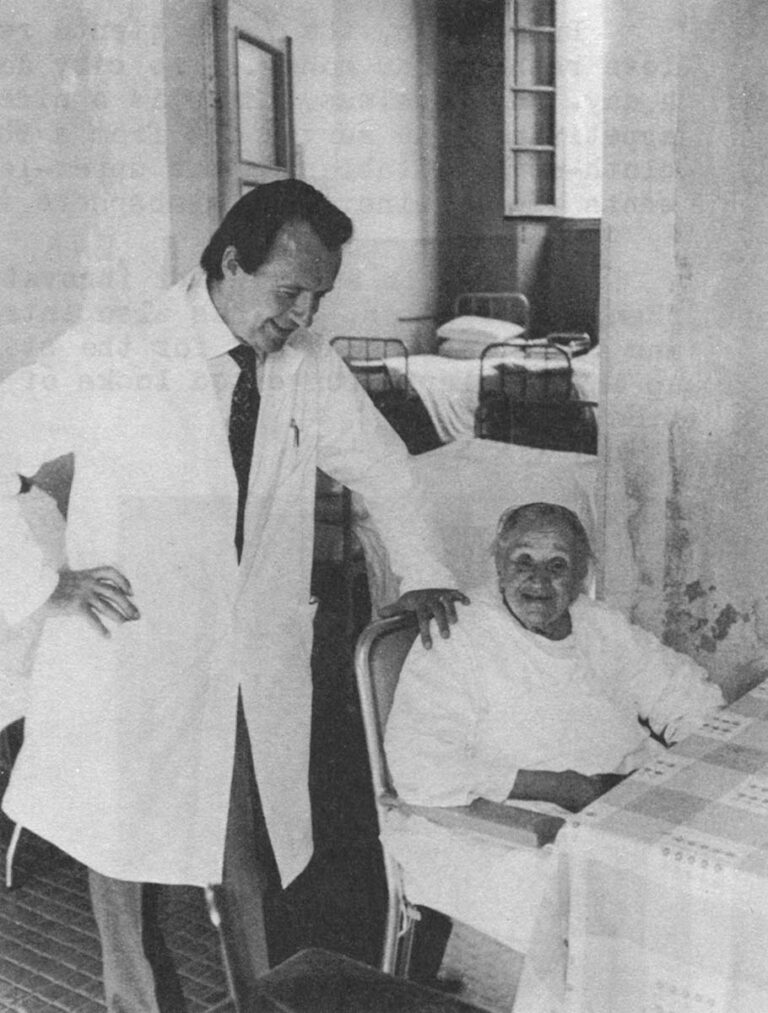

Dr. Ugo Cavalieri, medical director of Pia casa di Abbiategrasso, a home for the aged outside Milan, decided reform begins at home. At first look at the archaic, cavernous structure, complete with courtyard and cloister, I was dubious.

But within, the 750 patients receive exquisite care. One financed by love rather than money. The city doles out a meager five dollars per patient a day. Nonetheless, there is a nice portion of meat for lunch, part of an appetizing menu served hot from a thermal cart. Patients dine at small, cloth-covered tables on the upper-level balcony, complete with daily allotments of red wine. The atmosphere is that of an outdoor city cafe.

The wine is a Cavalieri innovation. They enjoy it and it’s good for them, he explains. He has also introduced brush-up courses in geriatrics and “Cavalieri humanism” for the staff of 130 attendants. Results show up in the alert, contented looks of the patients and exchanges of affection.

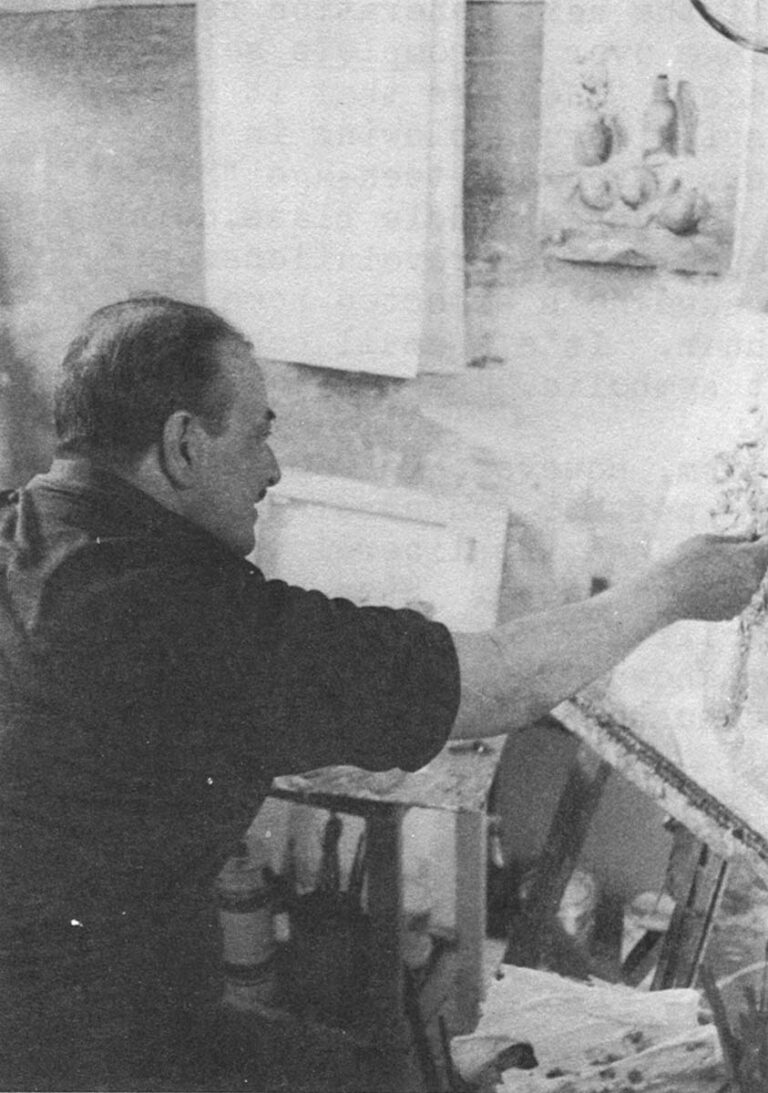

There’s no budget for occupational therapy, but individual talents are ferreted out and encouraged. Several men paint, and Antonio Agostinetii, of Trient, is the resident artist. A stairwell landing was set aside for his “studio,” and his still-lifes and pastoral scenes decorate all the walls. Five years ago, another institution had branded him an alcoholic psychopath. Here, given something to do, both problems disappeared.

In the women’s ward, a tiny lady swathed in white night gown paused in her lunch and reached for the doctor’s hand. She beamed up at him and said, fondly, “Ah, the professor is always in such good form. It’s because he deserves it.” A bit embarrassed by the declaration, Cavalieri nonetheless smiled with pleasure.

“They have confidence,” he said, “because they know we care.”

Here, then, is another kind of “family.” Perhaps that is the secret of it all. What Antonini called a “moral linking” of person to person. “We give to each other and give a lot,” he said. “We can’t live alone.”

Will the next generation really change over to complete self-centeredness? Odds are that it won’t, despite vogues blowing in from the West. Even the teen-age “Maoist”, of the upper middle class, quickly leaves fellow “revolutionaries” because he’s expected home for dinner. It’s a small concession, but symbolic.

Momism, however, is something else. It’s neither contemporary nor chic, complained the liberal women’s magazine Amica. Stop playing the sacrificing mother and martyr, it commanded. Demand equal status with you husband, and “get with it.”

“Never mind,” one Italian mother smirked. “We know when we’ve got it good.”

Received in New York on October 12, 1971.

©1971 Nada Skerly

Nada Skerly is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. This article may be published with credit to Miss Skerly, The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star, and The Alicia Patterson Fund.