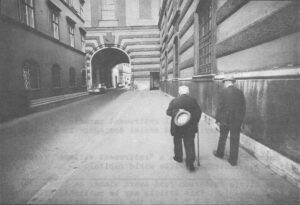

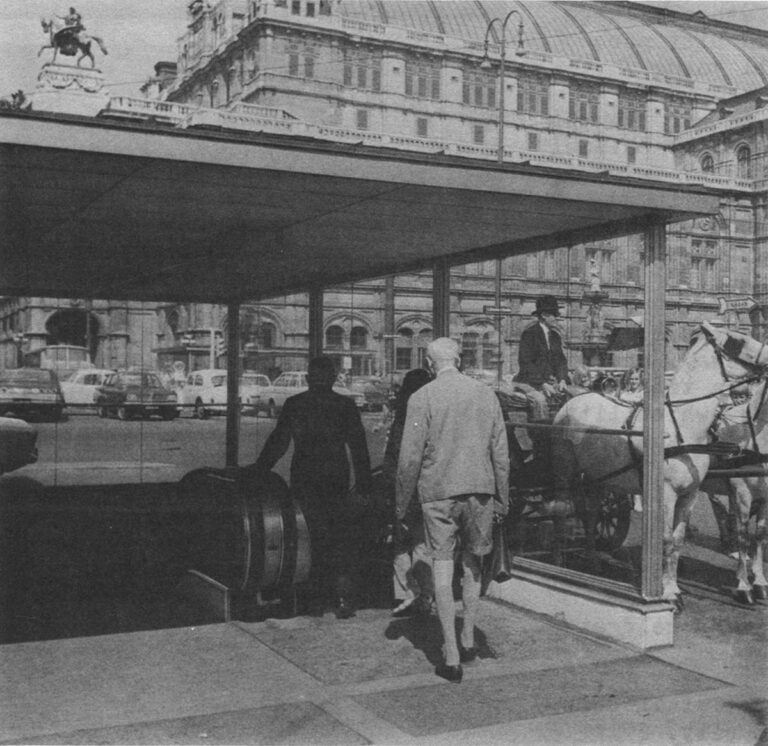

Vienna is one of the few natural retirement paradises left on earth. Here the aged have both numerical and social dominance in a unique 19th century operetta setting.

Call it “Leisure World East” – a “retirement village” spread over an entire city, a fascinating onetime world capital.

Now it belongs to the aged. Unequivocally, Vienna has the largest elderly population of any metropolis in the world – fully 36 per cent of its 1.6 million inhabitants are over age 60.

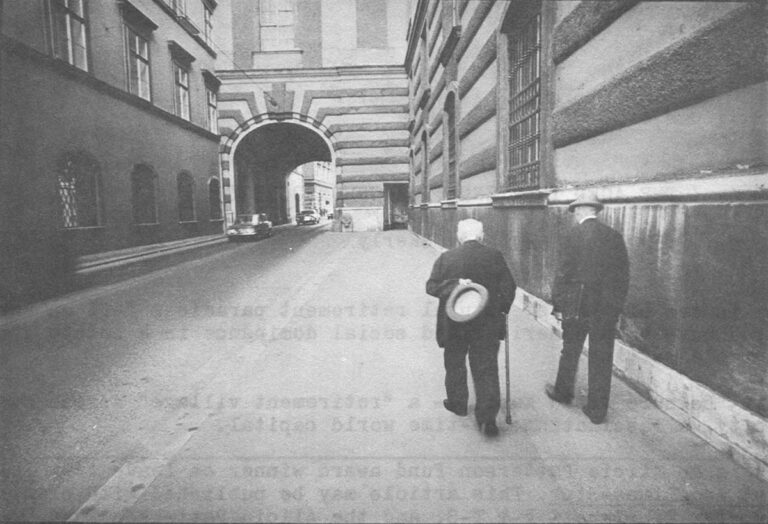

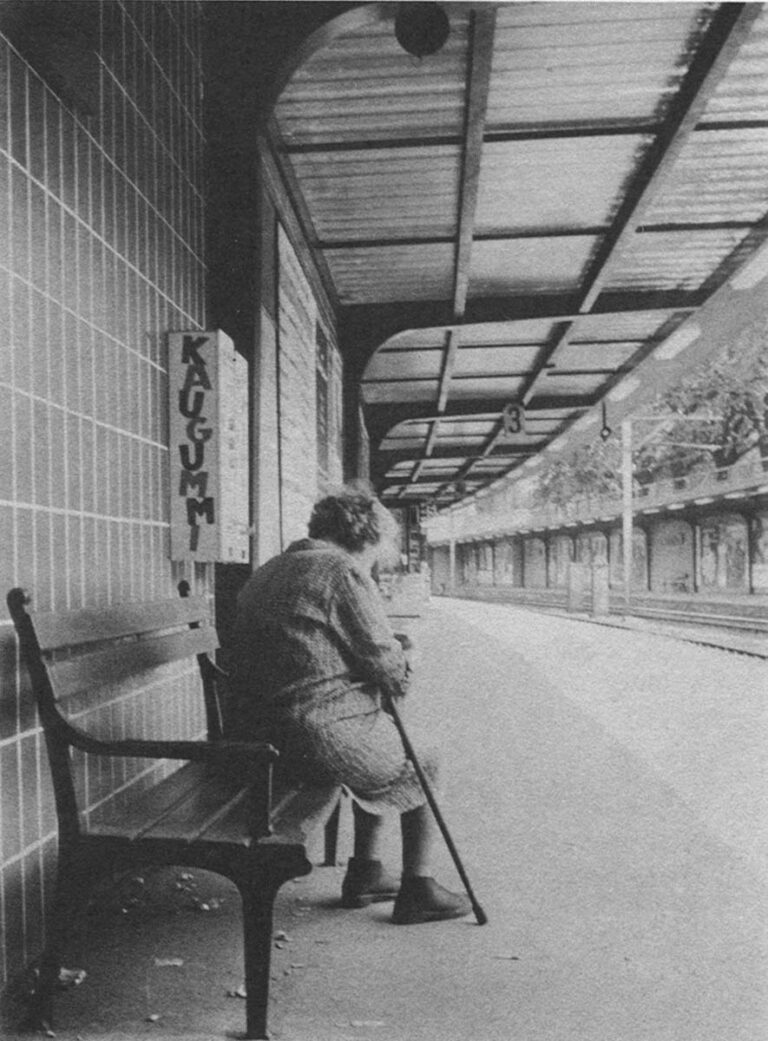

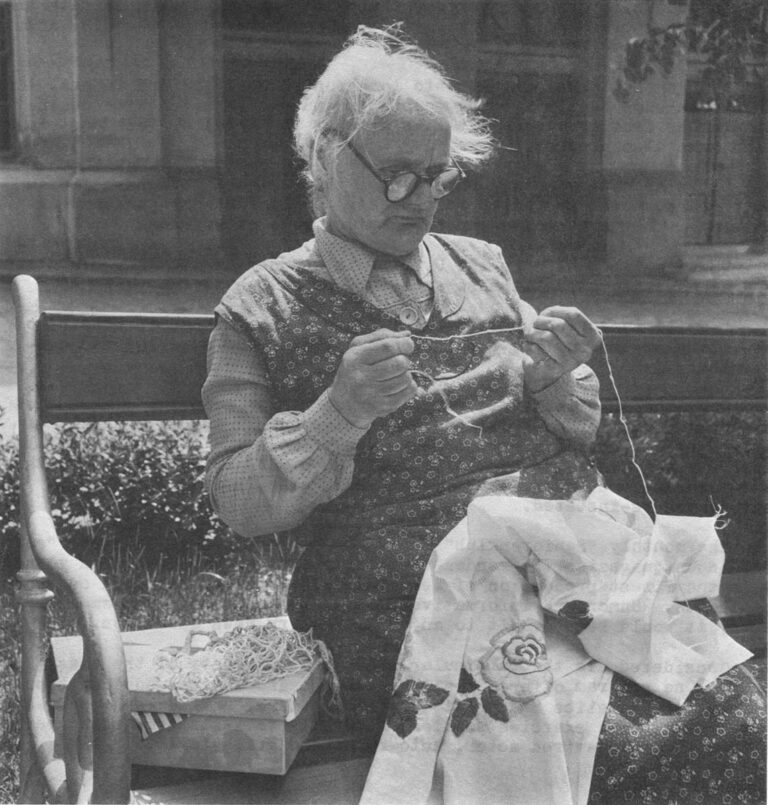

You see them everywhere: White and gray-haired heads bobbing through pedestrian traffic, elbowing onto streetcars, at the opera and concerts, in restaurants, snack bars and coffee houses, jamming food shops and stores and on the literally thousands of park benches.

Most were born here. Many American retirees, including three former U.S. ambassadors chose to settle here because life is cheaper and pleasant. One has the advantages of a highly cultural, compatible and secure community (no rowdies) and none of the arid, highly organized atmosphere of a Senior Citizen ghetto in the U.S.

The history books say Vienna died along with the emperor and the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. But no one bothered to tell the Viennese. For over half a century, the older generation has defiantly held back the clock. It persists in perpetuating a life style almost extinct in the contemporary world.

“Wien bleibt Wien,” they smugly say. (Vienna remains Vienna) Nothing ever changes. But not all of it is sweetness and cream cakes. From observing this patriarchal society, Sigmund Freud got his theories about repression and authoritarianism.

The young who chafe under the yoke often move away. Those who stay may eventually imitate the life patterns. Hansjorg Repa, 35, a commercial artist, laments, “We feel ruled by the old.

“We live with them,” he adds, “not they with us.” In most Western societies, the reverse is true.

Leopold Rosenmayr, sociologist at the University of Vienna, concedes, “Tradition is good for the aged, but not for the young.”

The gerontocracy is sustained by numbers, a Byzantine bureaucracy attitude toward life, and Freud.

It is good to be old here. The balance is in one’s favor. Dr. Bruno Kreisky, Austrian federal chancellor notes, “The aged are more content and make fewer demands than youth.”

Tradition rather than rationale feeds bureaucracy. An older man makes the best official because experience rather than ideas counts. Bright, ambitious career men of 40 are subdued with a fatherly laugh and the reminder, “Du bist noch Jung.” (You are still young.)

It takes years to survive the pecking order and the “Amtschimmel” (red tape) exacerbated by “stampism!” (A mini official has one inked official stamp and secures more along the way up.)

One must also perfect obsequious niceties, oiled with a little baksheesh. Then, someday, one may retire as a “Hofrat,” a title leftover from the monarchy, which literally means “Counselor to the Court.”

With it, you can stretch the small civil servant pension further. A Hofrat is on the invitation list for gratis tickets to theatre, opera and concert premieres and for official state functions held at numerous city palaces.

Titles are essential in this monarchy-preoccupied city. It’s in keeping with the waiting-for-the-emperor aura once brilliantly satirized by Russell Baker, New York Times columnist.

Connections are also a mainstay. A good part of growing old gracefully here, as Jewish repatriates can tell you, is knowing the right people. And a little “Schmaeh,” (honeyed words) can sweeten the simplest life. It can make the difference in the size or even existence of a pension, a 12 dollar versus 60 dollar apartment rental, a 10 per cent discount on, purchases, good medical care, a choice cut of veal steak at the butchers, or a generous slice of apple strudel from the waiter.

“Man muss sich auskennen,” says the Viennese. (You have to know your way around.) They thrive on improvisation and admittedly plant a few gratuities and hand kisses, actual or verbal, in strategic places.

Good eating requires less ingenuity, but exacts more effort. Food is a raison d’être. When asked what is important in his life now, the retiree replies unhesitatingly, “Health and good appetite.”

He may be limited to a laborer’s pension, which varies between 80 and 120 dollars per month per couple. But he won’t stint on food. Many old flats are bereft of plumbing (there are community toilet and water basin in the corridor), and have wood-burning, upright ceramic stoves. Nonetheless there is Wiener schnitzel (breaded veal) on the dinner table. (A television set has also become a necessity.)

The lone elderly have no meal problems. A local “Beisel”, a type of pub with excellent, simple food, offers a three-course menu for only 80 cents. That includes a delicacy like hot apricot dumplings which mother never knew how to make.

Dessert is a way of life. It provides an excuse to meet lady friends someplace for a mound of whipped cream, cake and conversation.

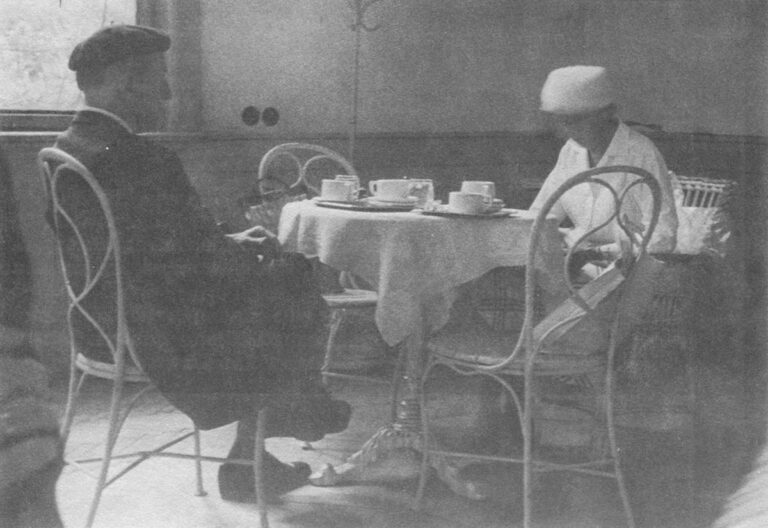

Men go to the coffeehouses where they can sit for hours and read, or receive telephone calls and visitors. Nine in the morning or four in the afternoon is a good time to catch Herr Hofrat or Herr Meister (retired handworker) bending over local and international newspapers strung on carpet-beater-type bamboo racks. For the cost of a cup of coffee, about 24 cents, he enjoys the privileges of this club-like “office” and second home. (In winter, it’s usually warmer than the apartment. Central heating is still uncommon, even in wealthy homes.)

The waiter greets him effusively as a regular customer, trades maladies or gossip (he, too may be over 60), and brings an extra cube of sugar for the guest’s dog lying under the table. (In winter, he also provides a pillow 80 Schnupsi won’t catch cold.)

Toward five or six of an afternoon, one may go to a Heurigen wine garden to judge the new vintage. The wife brings along a picnic lunch and perhaps a widowed sister or friend. Eventually all are part of a long table of equally high-spirited sippers and singers. A Schrammel trio (with at least one old-timer as violinist or accordionist) serenades with a few teary ditties about love, and “Vienna the City of my Dreams…” As the evening progresses, there’s a request for “How Nice to Become Old in Vienna.”

The Heurigen locales are dubbed the Viennese psychiatric couch. Freud is for “export” only and the very sick. Why pay for counsel when you can let off steam with a few kindred spirits and forget the worries of the day?

Another psychological escape hatch is the “Ehrenbeleidigung,” or suing someone for “offended honor.” Public servants get preferred treatment so you don’t call a policeman a “fat noodle,” or like epithet. But if your cranky neighbor or her grandchildren get on your nerves, tell her off.

If she presses charges for offended honor, it becomes delightfully official and repeated again in court. The process costs about 60 cents. Many claim it is cheaper and more satisfying than taking a tranquilizer or a shot of whiskey. One Vienna daily has the edge on competitors by publishing a daily transcript of the saltiest Ehrenbeleidigung cases.

The older Viennese enjoys his role of eminence gris both in public and in private. For one, his disapproval of the relaxed younger generation is vocal, loud and often embarrassing. Many a casually dressed student, foreign and Austrian, has braved a tram ride amidst a barrage of disparaging remarks about “hippies, long hair, minis, maxis and blue jeans.”

Particularly in the middle class families, says Prof. Rosenmayr, “the aged tyrannize both their middle-aged children and their grandchildren. It is they who determine a young man’s choice of studies or job. The marriage is off if grandmother doesn’t approve of the prospective mate. If it is on, it is she who designates the wedding format and feast. She knows best what a girl of 18 should and should not do, as does grandfather for the male offspring.”

Rosenmayr says, “The aged know what it means to have long hair and the right clothes to wear and they express themselves so clearly that it must be true.

“It’s not just a matter of conforming,” he continues, “but an intensity of personal influence which forms an emotional bridge between the generations. It is considered destiny to be mixed in with the tradition they embody. This is what gave rise to Freud.”

Dr. Walter Spiel, Freudian child psychiatrist, says, contentedly, “The social structure still remains at the point where Freud left off.” He also condones the ascendancy of the elderly. “Of course white or gray hair gives more clout,” he says. This reliance on “conservative and sensible decisions,” he feels, accounts for Vienna’s “splendid isolation.” Few fads or fashions take hold here. Even the Beatles were ignored. And there is allegedly no drug or hooligan problem.

“We may be considered retarded,” Speil concludes, “but there is no social unrest or hippy element. The storm is held back at the border. At 11 p.m., an older person can walk through the city, through the darkest park, without fear. We relish our cultural activity and our particular life style.”

Viennese complacency infuriates some foreign families living here. One American Embassy wife and mother, red-faced with emotion, says, “Here they admire the old and squelch the young. The child is treated as an adult at the expense of his own personal growth.”

Indeed you rarely see little Hansi romp like a child. In the park, he sits primly beside grandmother and hears her prattle about “Sit nicely, walk nicely, eat nicely, speak nicely, be quiet…nicely.”

“They won’t let him play with our youngsters,” continues the Iowa redhead, “because they say our kids are too loud and unruly. Hah!” she blusters, “just wait until his parents are out of sight. Hansi becomes a monster and bullies the other children. But don’t listen to me, it’s all in Freud.”

Force-feeding for adulthood follows an 18th century recipe. Hansi learns to bow stiffly from the waist, solemnly shake all men’s hands and kiss those of the ladies. His sister also kisses hands of older women. Both learn the Baroque sing-song phrases, e.g. “Good day most honored lady, kiss-the-hand. Grateful thanks for your thoughtfulness.” The conversational pattern carries over into trades or professions and astounds foreigners unaccustomed to such courtliness.

In speech, dress and everyday living habits, the young imitate the old. This contrasts drastically with the youth trend in the U.S. and other Western societies.

As a child, Hansi is put into long pants, necktie and fedora. On his own he soon adopts a bushy moustache and pocket watch with chain. Sister goes from formless, out-size dresses to Dirndl or folk costume which mama also prefers.

Girls accompany mother on shopping trips, learn to ignore frozen and prepared foods and stick religiously to old-fashioned homemaking patterns. They also learn the subservient role of wifehood.

Women’s Lib groups in the U.S. would shudder at the “harem mentality,” as one liberated Viennese architect describes it.

Despite festering undertones, if judged from an American point of view, life on the surface remains “Gemuetlich” (comfortable) and age-oriented.

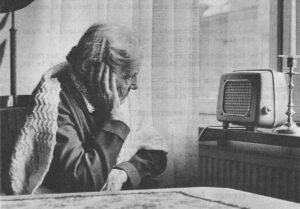

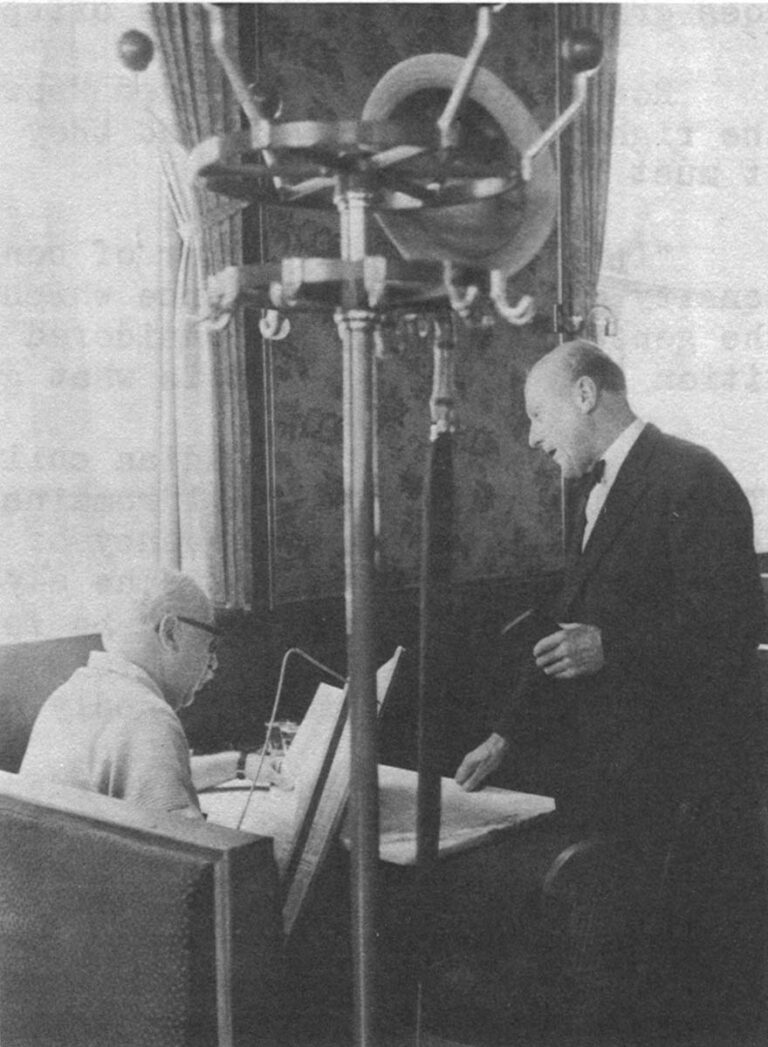

ORF, the Austrian state radio and television network, takes good care of the many elderly listeners and viewers. A favorite weekly variety show features a Nelson Eddy-type of host who beams thoughtful messages “to my old and sick friends.” When ORF decided to cancel this “old-fashioned” program, the loyal elderly sent in so many protests that he was re-instated.

The monthly “Seniorenklub” (club for seniors) is a 90-minute “entertainment magazine…a rendezvous for those who have remained young.” It is the finest production of its kind this reporter has seen on two continents. Humorous, informative, witty, well directed and smoothly paced, it would be a credit to any U.S. network news operation.

Considered are the particular needs and interests of the older adult. One program offered health insurance and medical advice, tips on fashion, cosmetics and nutrition, and lectures on geography and law. There was a short exercise portion, naturally to waltz tempo, and perky interviews with retired actor, auto racer and graphologist.

Holding it all together was a lot of music and a little Viennese operetta spice. A handsome waiter and waitress couple, who distributed cake, coffee and wine to the audience in the studio, flirted, joked and sang. Nothing in Vienna functions without some of the wine, women and song of lore.

Seniorenklub has prompted a viewer’s club which arranges holiday excursions and pen pal exchanges.

ORF also offers three other television news features and four weekly radio programs, all attuned to the elderly. There is even a “Dear Abby” of-the-air for aged letter writers.

Next year, to commemorate the Austrian national holiday, octogenarians will give their “impressions and criticisms of contemporary Austria.”

They should have plenty to say. At least about the externals of modern life.

“No, I wouldn’t want to be young again,” says a sweet-faced old lady sitting on a park bench. “There is less quality to life nowadays and more haste.”

She has survived two wars and a depression. “Looking younger,” she continues, “would be of no use to me. For the few remaining years, I have no wishes. I am content. I have lived and how I wish to grow old in “Ruhe” (peace).”

The sentiment is often expressed by the aged. They want their Ruhe. Men retire at 65; women at 60. But the quality of their Ruhe depends on economics as it does elsewhere in the world.

There is no government pension, only a contribution of 28 per cent by the state to private pension funds. Each work group – labor, farm, professional – has its own pension plan and one’s earnings determine the final amount of pension.

An estimated 350,000 Austrians subsist on 61 dollars a month. “Zum Leben zuwenig, zum Sterben zuviel,” they say (Too little to live and too much to die.) Fortunately, rentals are low, averaging 12 dollars a month. They were frozen by a 1918 law protecting war widows. It is still in force and a mainstay of the Socialist party election platform.

The Socialists also cater to the aged electorate via VORP (Verband der Oesterreichischen Rentner and Pensionisten). The retiree organization claims 300,000 members, mostly from the labor class.

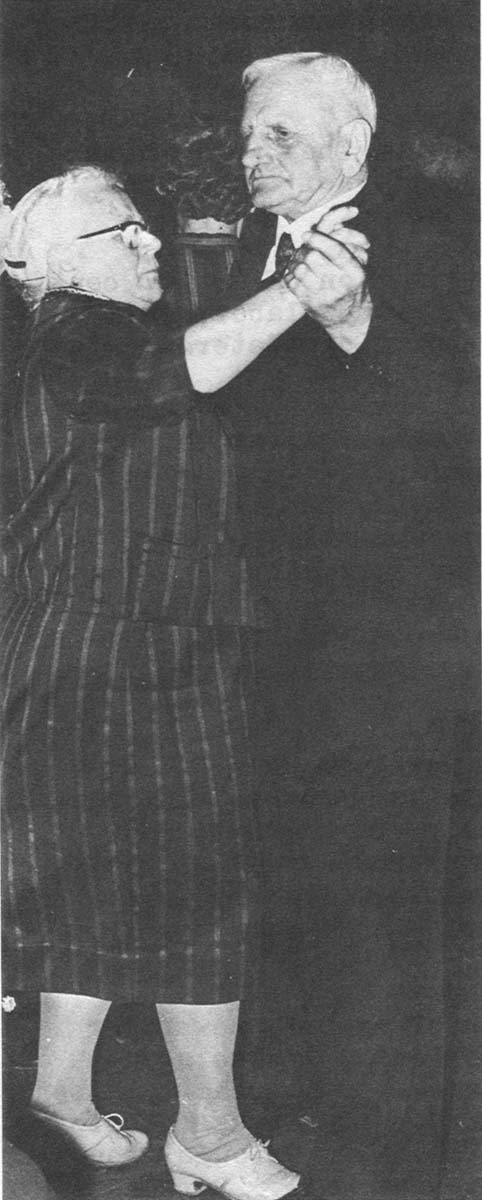

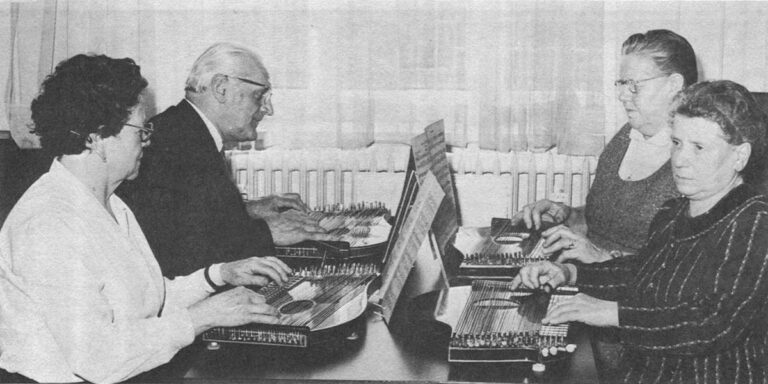

VORF members having a good time at dancing, sailing, and gymnastics.

Photos this page courtesy of VORP, Franz Blaha and Josef Keglevic

The conservative Volkspartei also sponsors such a club and holds a gala, annual pre-Lenten costume ball, but has a less developed program.

The VORP network of 200 neighborhood clubs offers swimming, exercise and dance courses, discounts on theatre and film tickets, Danube boat trips, and inexpensive holidays to Yugoslavia and Italy. A two-week vacation costs about 75 dollars.

Its best propaganda sheet, however, is a thick monthly newspaper mailed to each member household. There are excellent articles about health and nutrition (“not so much Schlagobers or whipped cream, please”), and house and garden. A Chronicle for the Older Generation has gossipy items about birthdays, accidents, robberies and deaths. Through “The Meeting Page,” one can request a pen pal, companion or mate. Personals are printed free of charge.

Samples: “Good looking widow, 69, wishes to meet well-groomed, intelligent man similar age…Pensioner, 83, 5′ 10”, agile, healthy, seeks independent, honest widow, minimum 60,as housekeeper. Salary open.

…Retired invalid, 54, 6′, seeks loveable, nice woman same age. Marriage possible.”

Others want male or female company to share “walks, coffee house visits, Heurigen drinking, bowling, bridge, etc. Many look to join choral or chamber music ensembles also created by VORP.

One afternoon at the main club office, zither music, singing and laughter came from somewhere in the building and sounded like 100 persons having a party. In fact, it was a zither group at practice.

Part of Viennese upbringing, whether one is rich or poor, is learning a musical instrument. Rosy-faced Hermine Lausacker, 70, a seamstress, studied zither at age 10 and has now returned to it. Johan Husar, 68, former jet engine mechanic, made his and also builds model airplanes.

The chatting stops for a bit and the group offers a touching song extolling the virtues of age. It is called “Whenever I See Happy Old People.”

How else do they expend their retirement days? Surprised at the query, but quick to retort, Husar says, “There isn’t enough time for everything. One goes into the green area (parks), wanders a bit, has a coffee, works in the Schrebergarten (small garden plots tucked among the hillside vineyards).”

The Viennese, by nature and inclination, is better equipped to meet retirement than his counterpart in other Western cultures. He is gregarious, thrives on gossip, and welcomes the chance to meet new people on the street, in a coffeehouse or restaurant, or over a glass of wine. Whether alone or with a companion, whether male or female, high or low income, the same traits of independence and self-sufficiency apply. He is well able to entertain himself, rarely stays at home to mope, and is not dependent on his children for companionship.

Even the grandmother, who helps out with the grandchildren, has her fixed tête-è-têtes. Like most Viennese women, she loves to tease and flirt and exchange compliments. She has her shopping rounds, chats with the butcher, dairy lady, pastry shop owner and newspaper kiosk attendant. If she craves a little more personal attention, she can also visit the doctor once a week. Not for the prescription, but for the waiting room tattle and more banter with the physician. All of it is gratis.

That is why the aged can say they have no further desires. They mean it. They have lived life, enjoyed it and made the most of every moment despite a dearth of money.

Those who would like to continue working past retirement age have a difficult time finding jobs. Except for established professionals, the market is tight for persons in the 40 to 60 age group. Opa (grandfather) may have clout within the family, but not at the factory.

Edgar Schranz, Socialist member of parliament, proposes a flexible retirement plan, which would shorten working days and extend vacation time. That would give the individual time, and part of his pension, to find another vocation.

Rosenmayr says the necessary changes are anathema to bureaucrats. He cites the example of a meals-on-wheels program (home deliveries for shut-ins) proposed 15 years ago. “Officials ignored it,” he says. “It was too much trouble for them to get it organized. Vienna is too bureaucratic to jump in and do things.”

As a result, there is also a shortage of good nursing homes. The city has built or renovated residential hotels into retirement-type homes for healthy aged. But 7,000 more are on the waiting list.

The Catholic nursing home, which offers the best care, also has a long waiting list and frantic daughters trying to make the right contacts to get a parent in.

It’s fun to be old in Vienna – as long as you are well.

Baroness Maria Waechter, 82, daughter of an old, wealthy Bremen family, lies with fever-swollen red eyes in a dirty, dank Viennese apartment. She has been unwell for months, but refuses to call in a doctor. “He might send me to the state institution as they did my poor sister,” she whines. “When I think of how she died….” Her voice trails off in sobs.

It has been three years since our last meeting. Then, despite advanced years, she had a fashionable salon attended by international writers and artisans. Now that she is ill, no one calls. The cleaning woman is hospitalized so no one attends to shopping, cleaning or laundry needs.

The servant pantry and kitchen, separated by an outdoor corridor, contains an archaic wood-burning range and tiny cold-water basin. Plaster is falling from the coiling and the area looks war-devastated. The landlord hopes for a vacancy soon and doesn’t bother with repairs. In winter, the baroness huddles by a miniature pot-bellied stove and tries to keep warm with hot teas.

“Where would I move?” she asks. “Where would I put my things?” Valuable antiques and objets d’art cram each dusty corner. “No. I could not move,” she adds, pointing to the 18th century carved molding near the coiling. “I love my architecture.”

She is a pathetic figure. Her once brilliant mind is dimming. She cannot recall the date, time of year or current events. Instead she dwells on girlhood memories: The horse her father had bought her and gay, international dinner parties on the family estate in Germany.

A Viennese niece and sole heiress rarely telephones. It doesn’t occur to her that auntie might appreciate a breath of fresh air, a trip to the countryside.

“Maybe by next winter, I shall die and it won’t matter,” says the baroness suddenly.

One turns away in pity and frustration.

Other aged aristocrats, and the imperial city is teeming with them, manage better. As long as they have health and family. Money is not essential. The title guarantees invitations to foreign embassies, weekends at the summer castles of friends and VIP treatment from local shopkeepers.

You can see some of them sipping vermouth at 11 a.m. at Demels, former confectioners for Emperor Franz Josef. Now, before the lunch crunch of American tourists, they are ushered to the back tables of the Smoking Salon. Conversation of the grande dames who congregate is something out of a French novel: Parties, dressmakers, love affairs and travels. In the afternoon, the aged playgirls move onto an art exhibition or opera dress rehearsal, followed by a cocktail party and dinner.

Working gentry like Count and Marquis Piatti, 70, juggle busy commercial and social lives. He has a dairy business, a Vienna apartment jammed with precious antiques and paintings, and the Renaissance castle of Loosdorf. His life revolves around hunts in the fall, and private balls and musicales in the city palaces of friends in the winter.

The pattern is there. Nothing changes. Wien bleibt Wien. The future? Repa, the young artist, shrugs his shoulders. “In the past.” he says, “youth could not and did not. Now we may, but do not. Perhaps another generation will also do.”

Received in New York on September 2, 1971.

©1971 Nada Skerly

Nada Skerly is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. This article may be published with credit to Miss Skerly, The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star and the Alicia Patterson Fund.