Copenhagen, Denmark May, 1971

Daggi Boucherat shuffles slowly, painfully to the door and opens it with a cheery, English- accented, “Hello, won’t you please come in?”

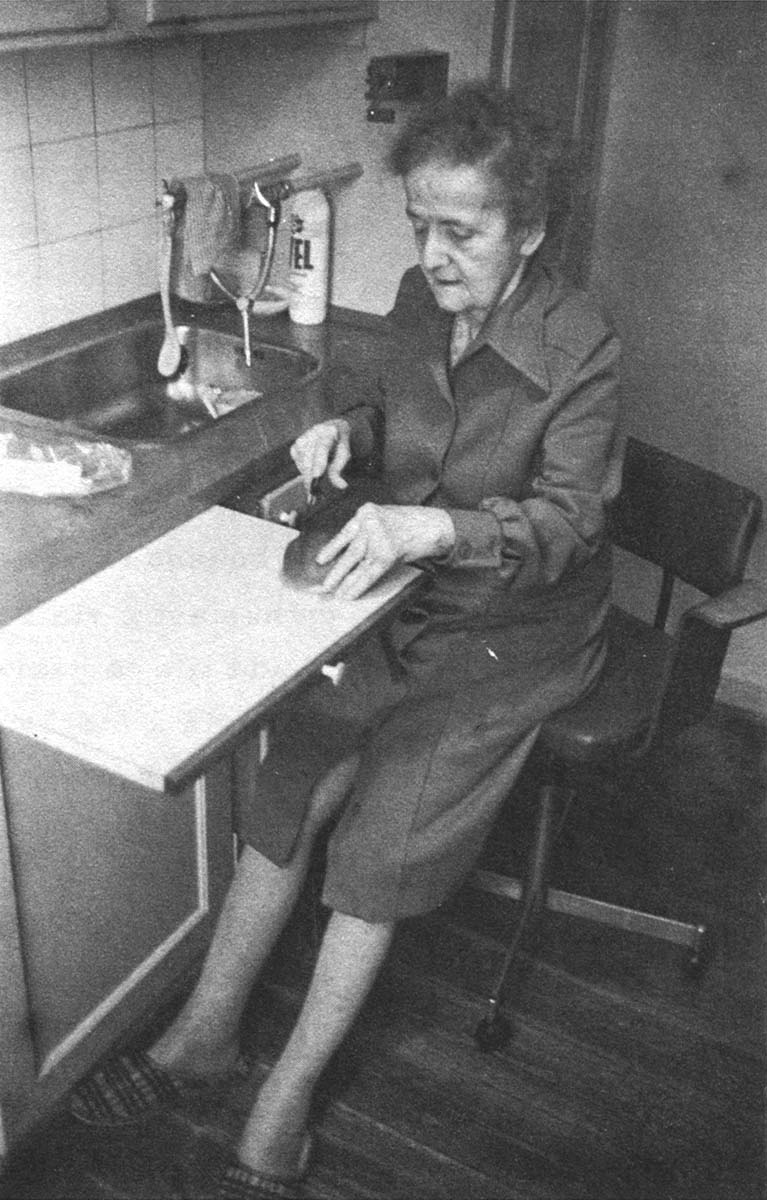

Crippled with arthritis for most of her 72 years, she has lived the last eight in a retirement apartment in the Copenhagen suburb of Gentofte.

Over a crystal goblet of Sandman port, the petite Dane, slim and elegant in a tailored, orange wool dress, tells of married life in Great Britain.

When her husband died, she decided, as do many fellow aged expatriates, to return home to Denmark to retire.

It would be foolish not to.

This is as close as you can come to retirement paradise. Legislation dating back some 80 years enables pensioners, as they are called here, to live as a privileged elite.

Talk with any Danish citizen and he will proudly tell you, “The problem you face with the elderly in the U.S. today is one we solved back in 1891.”

The normal retirement age is 67 for men and 62 for women. Pensions average 45 per cent of earnings or about 110 dollars per month for a single person.

It is the extras, however, that make the difference. The abundance of services and facilities is staggering. So is the tab.

Denmark spends one-third of its total income on social welfare services. Almost one-half of that budget is for the country’s 600, 000 aged. They represent over 12 per cent of the population and are increasing rapidly in number.

Mrs. Boucherat gets 145 dollars a month (everyone gets more because of extras) and pays 21 dollars a month for her government- subsidized, cozy, three-room flat.

Through the local municipality, she also could get a bevy of household renovations; telephone installation; wheel chair, cleaning, food, laundry and nursing services and free transportation to the podiatrist, hairdresser and to recreation centers.

Local fathers also pay for holiday’s abroad and adult study courses.

Of course there are also well-run retirement homes and geriatric hospitals. But only Gentofte has the money and leadership to build Tranehaven, a new 2.6 million-dollar rehabilitation center only for retirees.

The need was there. The aged comprise 17 per cent or 13,600 of the population. In another two years the figure is expected to jump to 15,000.

Hospitals are already jammed with the aged and retirement institutions are too costly to build.

Besides, the Danes have a horror of being sent to a hospital (there are no skilled nursing homes, as one knows them in the U. S.). It means the end of the road.

Dr. Vagn Porsman, director of Tranehaven, intends to reverse that trend. At least in Gentofte.

He seeks out older persons with minor problems and tries to rehabilitate them during a two or three month stay in his institution. Tranehaven is a cheerful, colorful, two-story geriatric health spa complete with Saturday night dances and musicales.

It has all the technical gadgetry of modern medicine and a mini operating room. Also a dentist, chiropodist and hairdresser. (In Denmark, foot care and a fresh hair-do are considered as essential as a cup of coffee and conversation. No institution or social club would be without them. )

Half of the building houses occupational therapy and recreation-handcraft facilities. A youthful, enthusiastic staff works with deteriorating muscles and sagging spirits to indeed add life to years. Stroke victims re-learn daily living patterns (for example via a mock-up traffic light for pedestrians). Others can learn to again be continent. A nutritionist lectures daily on good eating habits.

It’s a busy, active, happy place.

Dr. Porsman and his staff of therapists, social workers and psychiatrists know that the real work of rehabilitation begins at home.

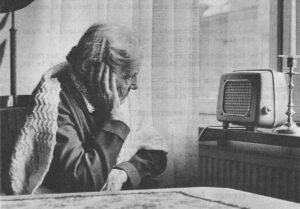

He tells patients to throw away the medicine bottle and “get active – more walking, reading and contact with the rest of the world via radio, television and other people.

“They should also be motivated to do for themselves, ” he adds. “Then they are healthier and have new courage.”

The Porsman technique has already worked “miracles” at the Old People’s Town (an old geriatric ghetto of 1850 persons). Almost 20 years ago he helped nine formerly bedfast elderly patients to walk again. In his first year at Tranehaven, 76 per cent of his charges have returned home. A few died and the remainder were sent to hospitals.

He is skeptical, however, about more experiments of his kind. “The concept is not popular with health authorities,” he says. “They do not want patients living outside in the community. They prefer having them in hospitals where they are less trouble and less work.”

They are not, however, less cost. Institutional care averages 10,000 dollars per year per person compared with home help at $3,000. Tranehaven costs Gentofte 35 dollars a day per person. The patient pays nothing.

Without a Tranehaven, Mrs. Boucherat would probably be hospitalized by now and bedfast.

Pre-Tranehaven, she could neither sit nor stand. After 15 weeks oil intense therapy, she learned to manage quite alone in her apartment.

She practices daily the stretch exercises and keeps fingers flexible with newly- discovered embroidery and weaving skills.

At Tranehaven’s instruction, the community bought her a new, firm orthopedic mattress, took out the old-fashioned doorsteps, and installed a bathroom shower with special levers.

For the kitchen, she has a special spring-seat, swivel chair on coasters. Also a pullout breadboard. Her prize possession is a wall-type can opener. “Quite unusual here, you know,” she beams.

During this particular visit Ilise Damgard, a comely, fifty-ish social worker, who makes rounds on a bicycle, made a note to have a new cooking unit installed.

Thrice weekly, for about 41 cents an hour (the community pays the rest), a lady comes to clean. For another 60 cents, Mrs. Boucherat has a hot lunch delivered from Tranehaven.

This kind of tailor-made care goes to wealthy residents as well.

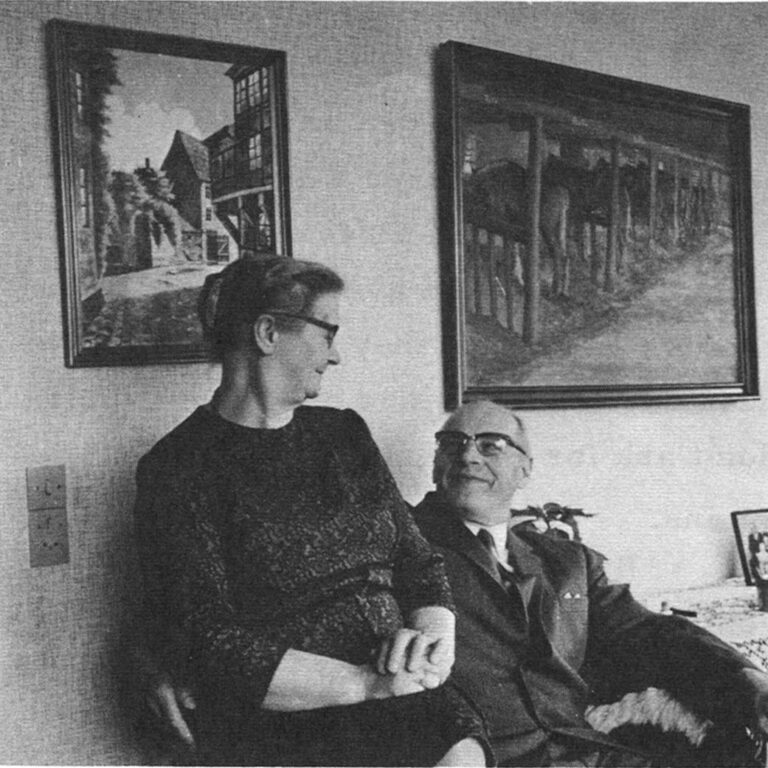

Ingeman and Mariella Holmsgard live in an attractive, two-story house tastefully furnished with Persian rugs and antiques. Mr. Holmsgard, 74, gets two-thirds of his former salary as a school principal. He also owns a summerhouse and an automobile.

His wife, 73, is a semi-invalid and both have been in and out of hospitals in the past year. They estimate it cost the state some 14,000 dollars.

Again at Tranehaven’s direction, Mrs. Holmsgard got a wheelchair, the kitchen chair and a rail for the toilet.

Their only complaint: No one to do the heavy cleaning. Out came Mrs. Damgard’s notebook.

No one seems to consider cost. Under a slogan of “more for all,” Gentofte is already into another project. It has harnessed Scandinavian Airlines System caterers for a mass meals-on-wheels program for the aged. “It certainly beats the expense of creating more nursing institutions,” says one of the planners.

Services elsewhere vary with the local tax base. The Danes complain most about the inner city of Copenhagen (where the poor live a stone s throw from the famed Tivoli amusement park.)

Other progressive communities talking about rehabilitation are Aarhus and Odense. It is a new concept. Until 1965, hospitalization was the normal treatment for the infirm aged.

Nathalie Lind, minister of social welfare gives top priority to “Doing all possible to allow the older person to stay in his own home.”

Own big debate, she says, is whether to bolster preventative care or build institutions. Currently, the state subsidizes municipalities at 75 per cent of cost to build geriatric hospitals and at 37 per cent for home care.

Mrs. Lind wants to stem the tide. “External welfare is cheaper and better than institutional care,” she says. She also seeks solutions to the problem of loneliness.

The subject of loneliness, of lack of contact and of neglect from adult children crops into every conversation with the Danes about their aged.

Even Dr. Porsman with his “magic wand,” gets frustrated with “disinterested families and objecting spouses.”

“It is not a question of money,” he says. “But of attitude. The more welfare there is, the more the feelings of the family disintegrate. The state creates institutions and the family says, ‘You keep ’em.'”

At Odense, a few blocks away from the birthplace of Hans Christian Anderson, a teacher worries about creating “trivsel” for the elderly. Roughly translated, it means “contentment” or “happiness.”

“We visit our elderly parents as a duty and they feel it is a duty,” says Christian Sorensen. “In the old days, I would read to my grandmother from the Bible and we would discuss and disagree. It was a wonderful experience for both of us. This is trivsel.”

Now the state is trying to provide trivsel.

The ministry of social welfare has asked Sorensen to plan a curriculum for home-aides who eventually will work with the elderly in their homes.

Courses will begin this fall and include gerontology, civil law (to sort out re-marriage or inheritance questions), dramatics (for reading aloud) and leadership training. The last, says Sorensen, is to learn how to bypass bureaucracy. “It is all a matter of knowing which buttons to push if you want to get things done.”

So equipped, graduates will be able ‘to produce trivsel for their elderly charges. Surrogate family. A cadre of professional “careers.”

Danes pay over 40 per cent in income taxes for their social services and they squeal often and loudly for quantity and quality.

They complain about taxes, but boast of new 2. 5 million-dollar police launches with Rolls Royce engines. Also a new Copenhagen general hospital, which will cost $145 a day upon completion in 1973.

They were scandalized when the daily Politiken reported conditions at the Norre geriatric hospital. One reporter noted eight patients to a room “lying apathetically like waxen dolls.”

Personal inspection showed some crowding perhaps, but flowers on nightstands, spotless linens and bed clothing, and a total absence of the urine smell prevalent in some of the best U.S. extended care facilities.

The practical Danes also solved the problem of bedsores three years ago. Each patient has a contour muslin bed pad filled with polyester “snow.”

A spot check of retirement homes also showed this penchant for cleanliness. And orderliness. Residents are allowed their own furniture and walls are thick with family photos and momentous. Windowsills seem to sprout green plants.

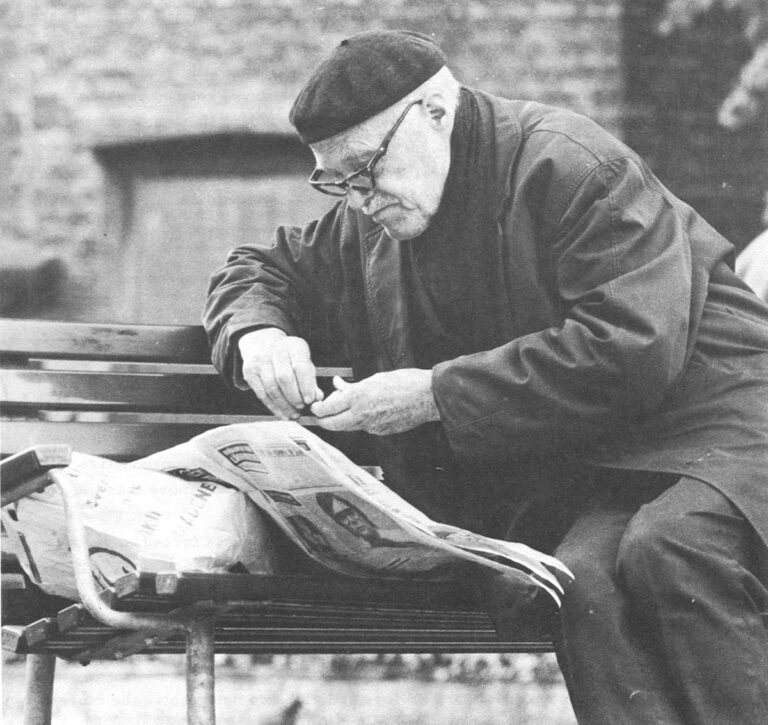

But there is no activity. Most of the inmates just sit and stare. A few work at embroidery. Some read newspapers.

At the Old People’s Town, a poor man’ s “Leisure World,” there are brave attempts at a Wednesday evening “Night Club” (translate coffee hour plus the ubiquitous “smorrebrod,” little, open-faced Dagwood sandwiches).

Average age at this one-time showpiece of Danish social welfare (circa 1937) is 85. Average pastime in the 10-acre compound of red brick buildings: Watching the hearse make its almost daily run to the round church in the central courtyard.

This kind of geriatric housing and hospital compound is being phased out in favor of a Peder Lykke Centret, a five million-dollar skyscraper built near Copenhagen airport. It is still an old folks’ ghetto, but vertical (16 stories) and modern. Even the stairwell railings are painted bright orange because vision dims for the elderly.

But the human problems remain. About 400 elderly residents have been transported from their small, home neighborhoods into one-room flats. There is an absence of greens, shops and neighbors. The site, part of the Copenhagen urban renewal program, is across from dilapidated shacks.

The rental brochure calls it “A home and a meeting place for old people. Its purpose is to make the inmates (sic) participate in a large -number of activities…parties and cozy gatherings.”

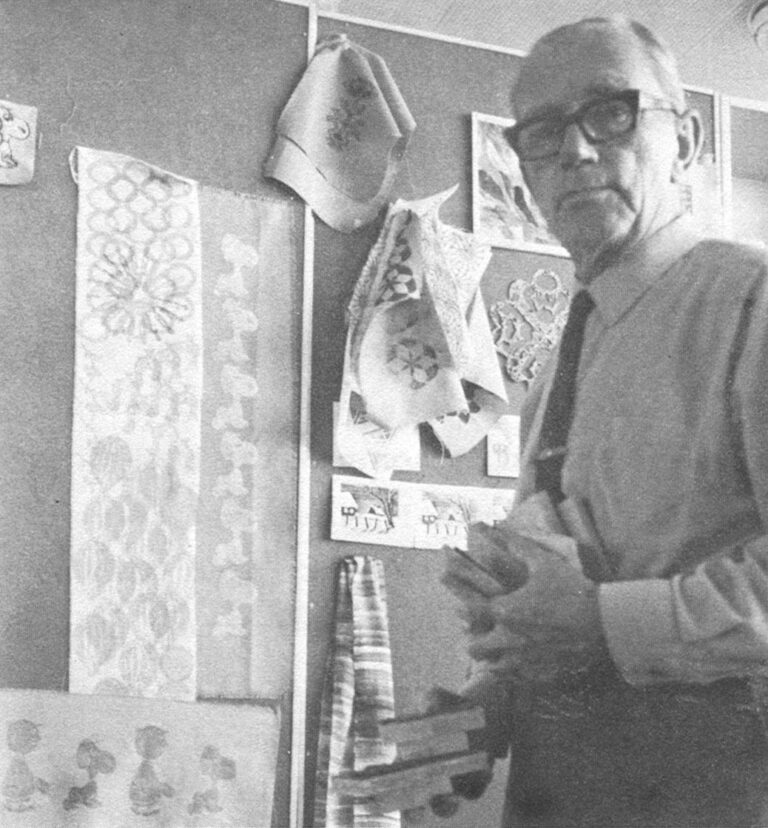

The best part of it for Karl Sorensen, 69, is the day center, a handcraft and recreation area where residents from the community, may get involved. He lost his wife 24 years -ago, has one son in Australia, and is working out retired life since leaving the shipyards a year ago.

Until the center opened, the one-time crane operator did not know what to do with his time.

Now he happily makes “Peanut” cartoon woodcuts and sells them, if he wishes, at Bette Nok, a shop for retiree handcrafts.

“I am not lonely anymore,” says the soft-spoken and well-groomed pensioner. “Would you like to see some more of my work?”

On Thursday, Sorensen joins other men in learning how to cook cheap and nutritional meals. The ladies have their turns on Fridays.

In the nursing sector of the complex, Kristian Carlsen, 80, lives in a wheelchair. But his private room is furnished with his own things, including an antique grandfathers clock, the Danish flag, and paintings of ships befitting a former seaman. Carlsen also has Tine, a large setter. Animals are “off limits,” but the doctor prescribed his one as part of the therapy. The dog stays.

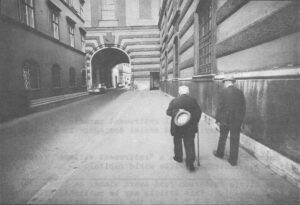

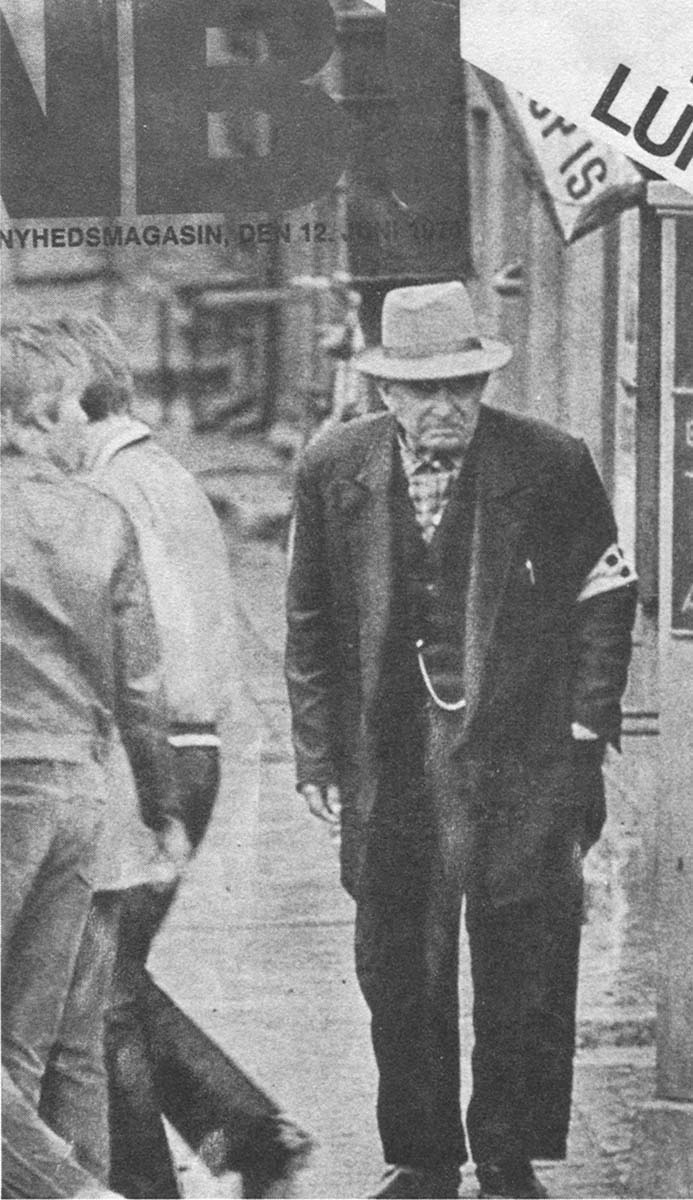

It may be very new and safe and comfortable, but “no thank you,” says Viggo Juliusson, 76. He prefers his tiny, third floor walk-up (with outside toilet) located in the worker’s ghetto near city hall.

To visit with Mr. Juliusson, a widower, one accompanies Johannes Nielsen on his rounds. Nielsen, 63, was a former professional Danish soccer great. Now he delivers the pensions. Ill health and several cancer operations changed Nielsen’s life and his attitude.

“Come with me,” he says. “Come to my old and sick people. They are my friends and most important in my life now.

“I am a lucky man,” says the always smiling, robust Nielsen. “With a smile and good work, you can do much for these people if you want to.”

Nielsen wants to.

For many elderly persons, he is the only visitor they have.

Doors are kept locked against gangster types who prowl the area. “One man was murdered in that doorway,” says Nielsen, pointing to a spot across the street from Juliusson’s flat. So he signals his arrival with a few bars of “Old Man River” in a lusty baritone voice and doors fling open in welcome.

Mr. Juliusson says it is unsafe to walk at night. But he would never dream of leaving his comfortable yet simple four-room apartment.

“This is his life, his neighborhood where he was born,” translates Nielsen. “It is all in his head.”

No, says Juliusson, he would not leave. A friend who moved to one of those retirement houses died a year later.

Juliusson and Nielsen joke a bit, enjoy a bit of Dubonnet and discuss America. Out come piles of Kodachrome photos. A sister and many nieces and nephews live near Boston. There are letters plus a campaign card of a Hansen in Westboro who had tried to unseat Ted Kennedy for the U. S. Senate.

“They write often and also send me five dollars each month,” adds Julius son, appreciatively, in talking about his only living relatives.

In another building, across the courtyard and near the outside toilets, Hilde Holst, 81, shares three squalid rooms with a son who is mentally ill. “Americans think everything is best in Denmark,” she remarks.

But would she leave her 300-year-old building? Oh, no! “My home is my castle,” she says.

Proud and sometimes removed from the life stream. But only a Johannes Nielsen would know about it. And someone like Inge-Marete Petersen who works with the elderly.

Mrs. Petersen, a housewife with two young children, scoffs at a sociological survey which purports there are few lone aged Danes.

“We would never tell a stranger our problems,” she says. “In that way we differ from Americans who immediately tell you their life story.”

“To the outsider, we may seem very free,” she adds. (Indeed abolition of the pornography law would point to that.) “We are in one way, but not in another. We are very private persons.”

Tourists stroll along the quay to the landmark of the Little Mermaid. There older women come to sit and pass the time of day. But one rarely sees them converse with one another. “They do not talk,” says Mrs. Petersen, “although they may share the same problem. One would never admit to the other that, for example, a daughter never visits.”

Loneliness extols a high price. “The suicide rate at holiday times in particular,” she adds, “is frightening.”

It took a long time to pierce the surface of the ever smiling and seemingly content older Dane. But when she did, Politiken reporter Anne Wolden Raethinge uncovered sad examples. Her series amazed readers who wondered, “How did you find out such things?”

Mrs. Raethinge portrays a former nurse now age 82 and living in a retirement compound.

“Medicine keeps us alive,” says the woman. “But it does not prolong the will to live. I have thought of suicide but I must stand it here because I believe in the after life.

“Here I am locked together with 400 other aged pieces, one more weak and senile than the next. Last winter I heard only the cries of the dying.

“On Christmas Eve,” says the interviewee, “I put out the light so no one knows I am alone and I lie quite still on the floor.”

In another instance, reporter Raethinge found a retired public official, now 85. He sips whiskey in the library of his well-appointed city apartment and says, “I am only hoping to disappear as soon as possible.

“One has to keep at a distance from children because they have much to do. We are only leftovers. The old cannot hang onto youth. It creates too much bitterness. Now I am superfluous.”

Mrs. Raethinge also said that some relatives come around only on the day the pension check arrives.

“Hov-Hov,” the Danish version of “Laugh-In,” satirized the scene for its viewers by showing a fat man driving his big car to the door of a retirement home. “I hope she hangs on until the car is paid for,” he is saying, “I’ve only got two years of payments to go.”

Last June, a Danish news weekly called N. B. wrote a cover story titled “We Betray Our Aged.”

In it, Hose Seierup, chairman of the Social Reform Commission, sums up the problem.

“One doesn’t think the old people are lonely, but maybe they do not want to come out with the truth. They are covering up for their children. A series of practical problems have been solved for the old, but the human aspect is left behind.”

To bridge the void, old age clubs partly subsidized by the government have developed in the last decade.

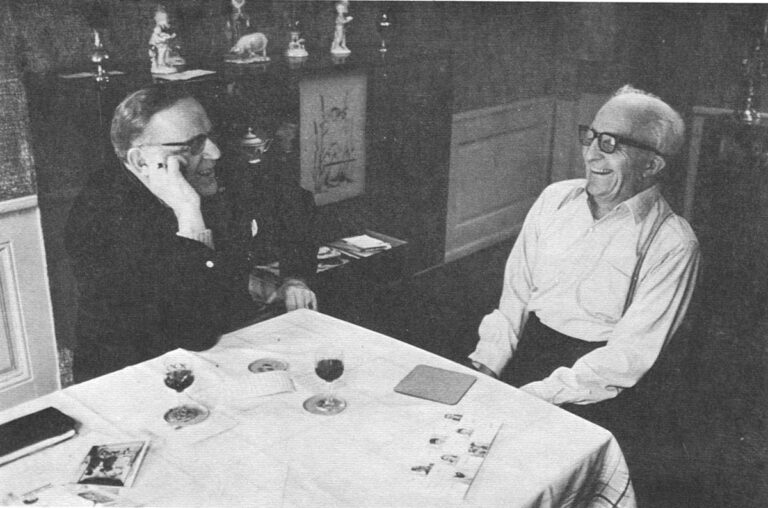

The most successful one – Pensionisternes Samvirke – was founded six years ago by Kristian Albertsen, a social democrat of parliament.

Colleagues are encouraged to form new chapters in their home districts. “It works rather well,” says club director Paul Bertolt, 26. “They have the contacts and the free car to do it.”

Bertolt recently flew to Holstebro in western Denmark to kick off a new club. About 1800 farmers in black suits and wives in print dresses showed lap for the free afternoon concert and pep talk about Samvirke and Albertsen.

The conservatives offer the elderly their “O. K.” clubs. The resulting competition over who will transport grandmother to a club activity (that’s provided too) causes one observer to josh that she can choose between the social democrat or the conservative car.

Her vote is important and the politicians are well aware of it. Those over 65 represent 17 per cent of the votes those over 55, a total 34 per cent.

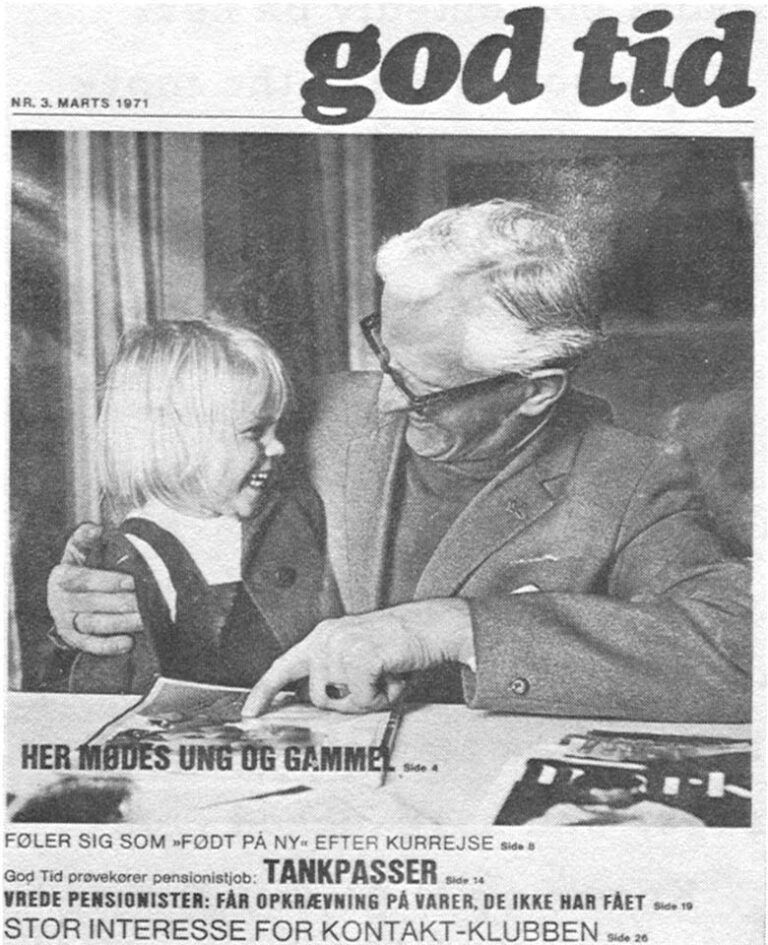

Albertsen’s club stresses fun and recreation and offers a smorgasbord of cheap movie programs, holidays abroad (81 dollars for 12 days on the Italian Riviera) and a peppy monthly feature magazine called “God Tid.” Appropriately, that means “plenty of time.”

Samvirke advertisement “Loneliness and resignation can be remedied.”

The pensioner’s need to fill time is what got Albertsen involved in the first place.

Albertsen recalls, “A constituent came to me and said he had hours of the day to fill as did I. But he did not know what to do about them. So here we are trying to fill them with a little fun and also creative learning.”

This is done through a type of “boarding school” partly subsidized by the government.

During the 12-day session, a retiree gets a complete physical examination and learns about nutrition, personal hygiene, new traffic patterns, consumer rights and current affairs. Something called “social instruction” cues them on services available in the community and how to get them.

At one such school, Beaulieu, on the outskirts of Copenhagen, a group of 40 older adults listen to a program of concert songs and jokes. Downstairs in the German-style beer cellar, complete with a Nevada slot machine, a few men play billiards.

Dagny Edith Petarson, 76, stands nearby and puffs contentedly on her stubby cigar. (Many older women smoke them. Mrs. Petarson prefers the more mild “No. 6.”)

“The club is the most, important thing in my life,” she says. For the former cleaning woman and widow of a hairdresser, this is the only past time. “I like the feeling of being together, the songs and the bingo,” she adds. “Other nights I watch television.”

Laurdizen Jorgen, 27, the director, says, “Youth wants and gets everything. So it is up to us to provide now.

“Doctors say their time is too valuable to hear about the loneliness of their patients. So we use this place and outings as alternatives to institutions.

Another large organizer of activities for retirees, and hard-nosed competitor of Samvirke, is the Lonely Old Peoples Club. Known as E. G. V., it was founded in 1910 by a minister for farmers’ death benefits. Since then, and spurred by Samvirke, it has got into retirement housing (Peder Lykke Centret is theirs) and club work.

But despite the rivalry, both organizations agree they are thriving because there is no room for grandma or grandpa in modern life with its small apartments -and small automobiles.

The major problem is finding the isolated elderly who really have no one, They estimate they are now reaching only 20 per cent of the elderly-who happen to be joiners, ambulatory and able to afford the entertainments. To find the others, Samvirke proposes to use conscientious objectors to canvass all neighborhoods.

Mrs. Petersen of Samvirke is also annoyed at the lack of variety in programs. “Everyone is pushed into weaving or woodworking or some form of handcraft,” she says. It is so “pop,” so unreal. The elderly should not have to do such busy work if they have never before been interested. You see these patient, intelligent faces and you know they do it just to keep the leader happy.”

“It’s okay for those on limited funds and the simple-minded,” says reporter Raethinge. “But others feel it is child’s play and they feel the worse for having done A when they go home.” There is nothing for the more sophisticated -retiree, she adds, who wouldn’t dream of joining such a club.

“My aunt is lonely despite the nurse and stream of visitors,” says one city welfare aide. “It’s too bad, but you know we don’t have time either. We work all week and on weekends we like to be by ourselves.”

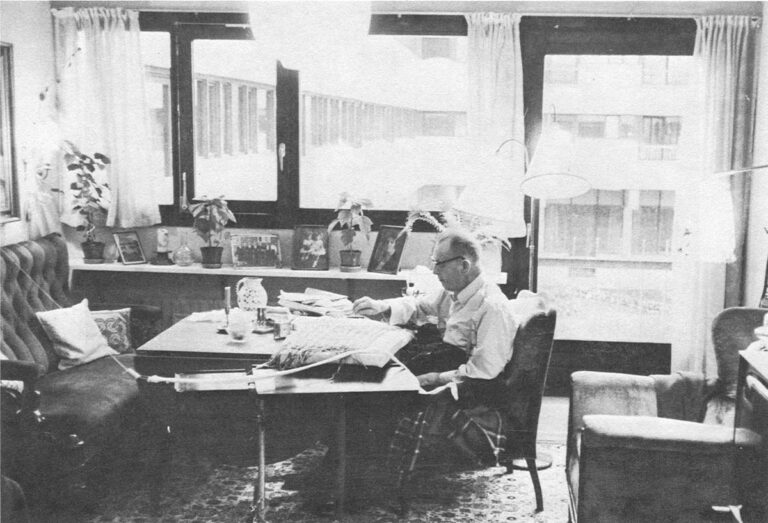

If he can help it, Christian Broendum, 65, and current chief engineer for the Odense-Lindo shipyards, isn’t going -to fall into a retirement trap. His predecessor, he says, has only television and boredom. Broendum, tall, trim and looking more like 45, has his gardening and his wood shop. He also hopes to stay on the job for another three years.

Since Denmark has a chronic manpower shortage, he’ll probably stay on. When he does leave, he will have the government pension plus a generous factory pension (still a rarity here). Also, income from “index,” a national retirement investment plan.

Elsewhere in the country, there is little thought about pre-retirement programs. When the time comes, one simply lets the state fake over. Sociologists predict the government will also eventually run clubs and the home visitor program. Currently, the latter job falls to the Red Cross.

Daily pleas come in for someone to visit the aged, but only a few hundred can be serviced, Of those, says Elisebeth Granzow, program director, three visits are the average.

“After that they are dead, or family comes, or they don’t ask for more,” she explains.

Bente Habro-Hansen, 30 volunteered to be a “patient friend,” as they are called, some 18 months ago. “My friends think I’m crazy to drive 12 miles each way once a week,” she says. “But I thought I would be old some day and it would come back to me.”

Her patient is a former ship stewardess, 85, who lived in the U. S. most of her life and finally came home.

“She is depressed,” says Mrs. Habro-Hansen “Money is not the problem, but lack of anything to do.

“I know it is sad to see organized visitations. But it is better than nothing.”

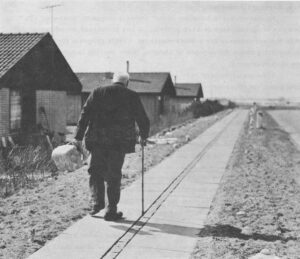

In the countryside, the social welfare system can also substitute for the family.

“Fifty years ago,” notes one resident of Holstebro, on the west coast of Denmark, “you had to take care of your parents and they lived in a little house right on the farm. Now you are no longer obliged.”

Downtown Holstebro, a revitalized new town complete with hot pants fashions and a discotheque, contrasts with the nearby village of Tvis where Vikings once built their ships.

In their sturdy, yellow-painted stone house, Bjorn Anderson, 69, and his wife, 60, contemplate retirement.

That means moving into town should their son decide to marry. It means leaving behind over 100 acres of land and the barn he so proudly shows off with its 21 cows, 30 calves, 10 sleek pigs and 100 piglets.

But he is surprisingly matter-of-fact about it. “It ‘s not good for two families under one roof,” he says, “My widowed father-in-law is with us because he is sick and alone. Other words, if one needs help, there are always neighbors nearby to look in on you. And here are home-aides sent by the community.”

There is also the new, 20-person retirement home. There, Marie Mogensen, 83, sits alone and looks at a wall photograph of her old family home.

At Hjorring, northeast of Holstebro, 18 aged persons sit in unlit rooms on a rainy Saturday afternoon. The home for the aged is called Sun House and is located in the heart of the farm community of Bjirgby. Population is 2000.

There are no visitors.

The activity room in the basement is locked except for a few hours a week. One lady in a black dress, typical garb for older farmwomen, fingers a newspaper report of her wedding day. There was a horse-drawn surrey. Also, much gaiety and music.

Relatives come on Sundays, says one administrator. But they deposit a bunch of flowers and then start checking their watches after 10 minutes. Time to leave.

In nearby Sankt Knudsby, Ejner Andersen, 66, and his wife live in a new brick house with central heating, freezer and modern furniture.

But to one side of the living room are two chairs upholstered in calfskin, (“my calves, ” says Andersen) and two paintings of the farmstead reproduced on wall plates.

Farmer Andersen looks a bit stiff in his white shirt and gray suit. Missing are the wooden clogs which every farmer wears in Denmark.

“I miss my fields,” he admits. A few years ago, the 300 acres plus 200 head of cattle went to his two sons. “When I had a bad day,” he continues, “I only needed a trip to the fields to feel better again.”

“Now the days are very long. I would like to have more to do. Most retired farmers feel they no longer have anything to do or to say.”

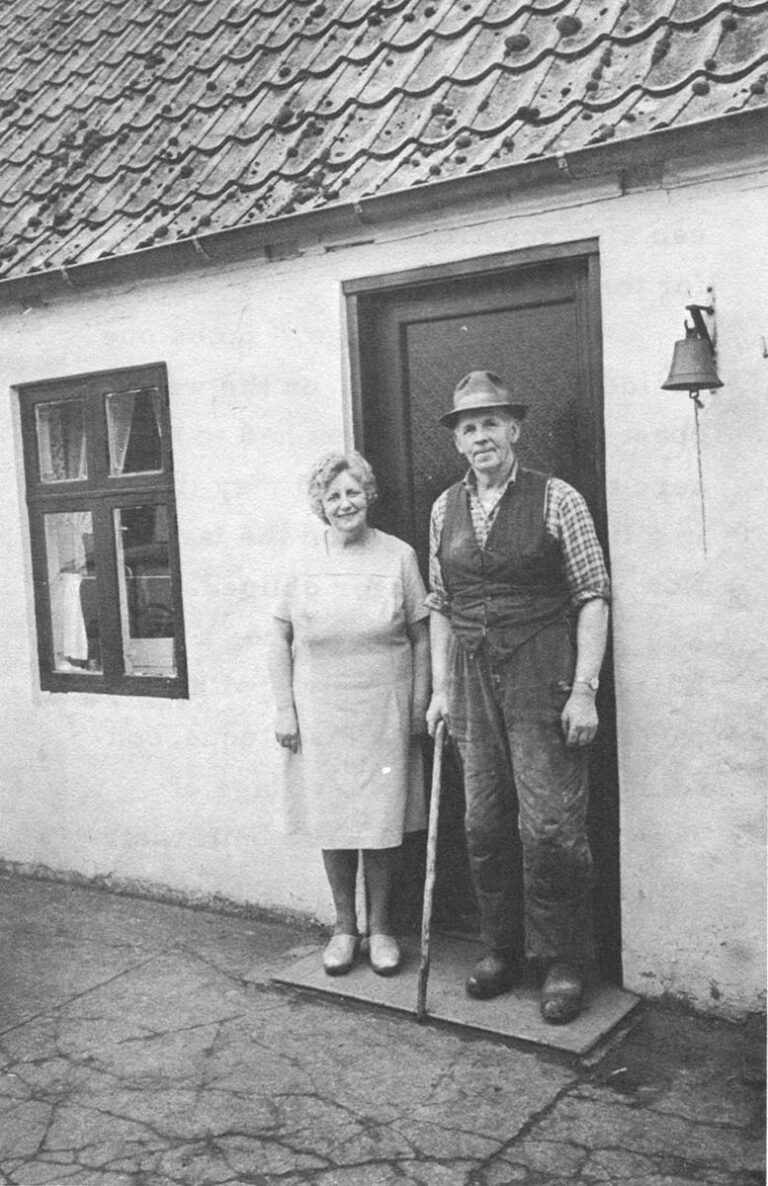

At Lonstrup, a fishing village 10 miles away, a few old timers recall the good days. Since erosion of the harbor, fishermen have moved to Hirtshals and other big fishing centers.

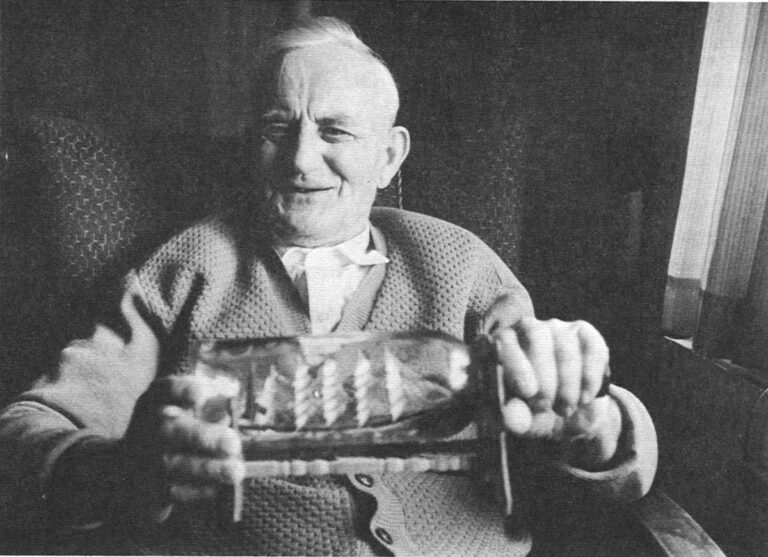

Carl Lauritzen, now 87, remained behind -with his wife, 80.

They live in a tiny, blue-shuttered stone dwelling the size of an American child’s playhouse.

Paintings of schooners line the walls and a photograph of a boy in an old-time sailor hat.

Lauritzen smiles happily when he says he was that youngster who at age 14 sailed a five-mast barque to Australia and elsewhere around the world.

It was then that he also learned the trick of making mini replicas in bottles – now something to sell to the tourists.

After some time at sea, he followed the traditional pattern: Returning home to marry and to work a fishing boat.

The grandfather clock ticks away the years. And Mrs. Lauritzen crochets as her husband says softly, “Remember when we used to get up at four in the morning and you would fix breakfast and I would go off to fish…”

The have their memories and each other. Letters come from family in America and their son, who took over the family house, stops by daily.

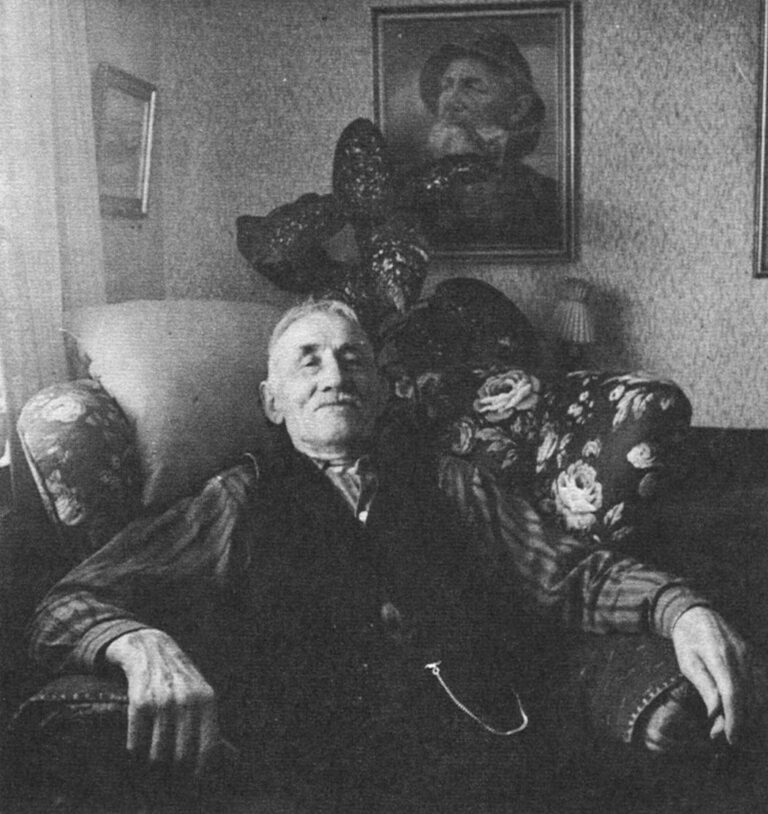

A block away, Jens Christian Andersen, 83, is alone and feels, he says, “A little disappointed in life.”

“The money is good enough,” says widower Andersen, thinking of the pension check. “And in the evening we play cards. But I still feel alone. I dreamed of being old together with my wife.”

He fished for 50 years, worked on the lifeboat and had a s mall mink farm on the side. Then it all went. The job and the hobby. Then his wife died and a daughter and a son moved 100 miles away to a better job.

Andersen lives alone in the neat, blue-painted house set close to the sea. He has his television; some wall lamps made of horn, and, of course, paintings of sailors and boats.

He’s afraid some day he will be faced with a retirement home. “There is only one room and a table. A lack of space and a lack of air,” he adds rubbing his chin thoughtfully.

This represents some of the present generation of retired persons. Those of the future will have greater demands, says Bent Hansen, editor of the social democrat daily Aktuelt.

He thinks pensions and services must be expanded. About 5,000 dollars a year would be an adequate income, he says. “One should not begin the fight for equality at age 67.”

Svend Jensen, leader of a 15,000-member strong “senior power” organization, feels that increases depend on the political activity of the retirees themselves. “Political problems for pensionists have to be handled by pensionists,” he says.

His group represents the aged pIus the blind and disabled. “But we don ‘t demonstrate,” he adds, “because we have it nearly quite well.”

The government, on the other hand, is in a quandary over how to pay for growing expectations.

At the present trend, says Mrs. Lind, “By 1985, the unproductive part of our population (the children and aged) will have two per cent more than the rest of the country.”

As a country lacking natural resources, Denmark is forced to produce and export to survive. But many individuals look to civil service jobs. They pay well, are prestigious and offer the best pensions.

“Ultimately,” says editor Hansen, “We’ll have to decide what we want and how to pay for it.” There is -no discussion, however, of cutting back on social welfare services.

Hansen also realizes that services and clubs do not resolve the more serious social problems. “They are only a substitute,” he says, “for life once lived.”

To solve the need for social value, for a feeling of individual worth, he suggests a flexible retirement program and less taxation on earnings. He also thinks there would be better social interaction if single apartments for the aged were mixed in with other family units.

“Social security,” concludes writer Raethinge, “is not enough. We will never solve the problem of being old. Two factors catch up with you. Loneliness and sickness.

“That is the hell of being old. Family turns away and in many cases friends die. Then you have no one.”

Received in New York on May 14, 1971.

©1971 Nada Skerly

Nada Skerly is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. This article may be published with credit to Miss Skerly, The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star and the Alicia Patterson Fund.