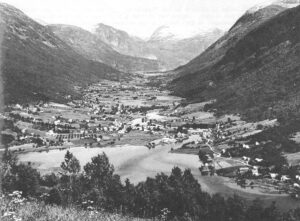

Stryn, Nordfjord, Norway

June, 1971

The two-seater seaplane sways gently over the majestic fjord country of Western Norway. Doughnut-shaped islands of gray granite, with frozen-lake centers contrast with others porcupine-thick with snow-dusted pine trees.

Here and there, amidst flat squares of green, thin curls of white smoke signal human habitation.

In the wink of a troll, the craft coasts into the town of Forde. By air the trip takes about 50 minutes. (Regular travelers have to rely on an overnight steamer.)

It helps to believe in the “little people” in this part of the world. Especially to get places. Legend has it that a troll saw a forlorn Norwegian stranded in Copenhagen on Christmas Eve and whisked him home to his family in an airborne sleigh.

“Modern trolls” command seaplanes. That is, are in the service of Ingemar Faenn, editor of the daily Bergens Tidende.

Other words the distances are still a problem in this land of mountains, islands and waterways. Norway, if flopped over, would stretch to Morocco. So faith in trolls comes in handy.

A bit of it kept the Vikings going. Along with a healthy dose of self-hypnosis. A conviction of invincibility.

The 20th century descendant is also hardy and resilient and has the longest life span of any man on earth.

But few could follow his recipe for longevity. Or would want to try.

Unlike his seafaring ancestor who lusted for new lands to conquer today’s Norwegian, the farmer in particular, works hard to keep what he has.

Only three per cent of the country (the combined size of New York, Pennsylvania and Maine) is arable. Another 25 per cent is forest and the remainder is barren wasteland and mountains.

One-third of Norway lies within the Arctic Circle and the winters are extremely long and bitter. Neighbors are few and far between and a man comes to rely on one person. Himself.

Fortune may encircle him with a vista of huge boulders and stubble growth. In this bleak wilderness, he spends a lifetime clearing a small patch for potatoes and a few cabbages.

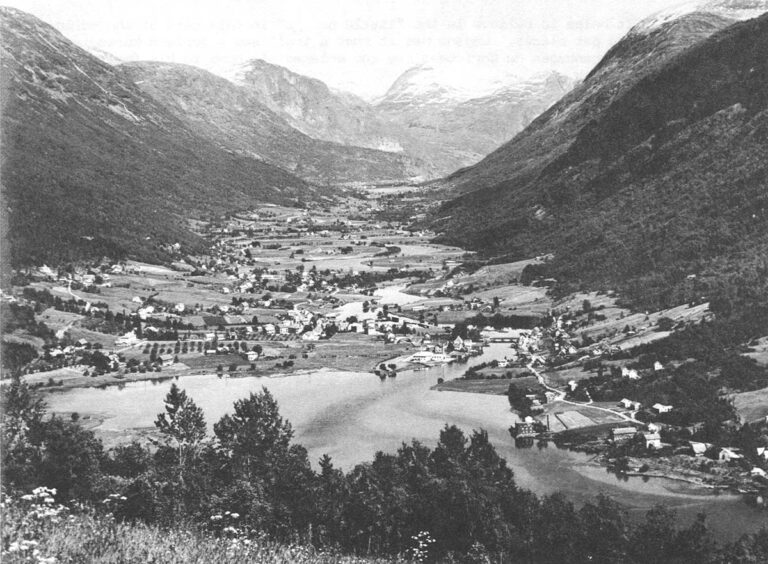

Or, if he’s lucky, he lives in the heart of the Nordfjord. And he awakens to a panorama of birch, pine and fruit trees silhouetted against snowcapped mountains rising grandly out of the calm, green fjord waters. They resemble so many clumps of gingerbread, their rounded tops sprinkled with powdered sugar. Except for the occasional soft bleat of the seagulls, he can “hear” the stillness.

Here are the villages of Stryn and Loen nestled 60 miles inward from the sea. It’s a five-hour bus ride from Forde along treacherous winding mountain roads.

The soil here, too, is rocky, but the landscape, captured in the film “Song of Norway,” brings peace to the heart. A sense of belonging, which 50 years abroad cannot diminish.

At the turn of the century, many did leave for America and “the better piece of bread.” For Minnesota and North Dakota. Patient, strong, honest Olav helped build the railroads and often served time in the U.S. Army. Often, he returned home to Norway. Home is where the heart is.

The “Odelslov,” an ancient Viking inheritance law, gave him a 20-year grace period to decide whether he wanted the property or not. It was his whether he immigrated to the States or someone else took title in the interim.

The pull of the old land, the invested toil, was greater than the promise of the new.

This was Sojn County, the poorest in Norway. Even today, half of the estimated 1600 denizens of Stryn are either ex-emigrants or have relatives in the U.S. Each summer, a new crop returns. Sometimes, to stay for good, “to walk in the places I knew as a child.”

The places are there. So are the traditions. In many ways, time has stood still in this corner of the world.

As in the Middle Ages, the peasant still takes his name from the land. Mail is simply addressed to Faleide in Faleide or Loen in Loen.

The Loens, owners of the deluxe Alexandra Hotel (there are a few innovations), became innkeepers when the first Britishers sailed in 1850. In those days, they brought their own silverware and wooden plates.

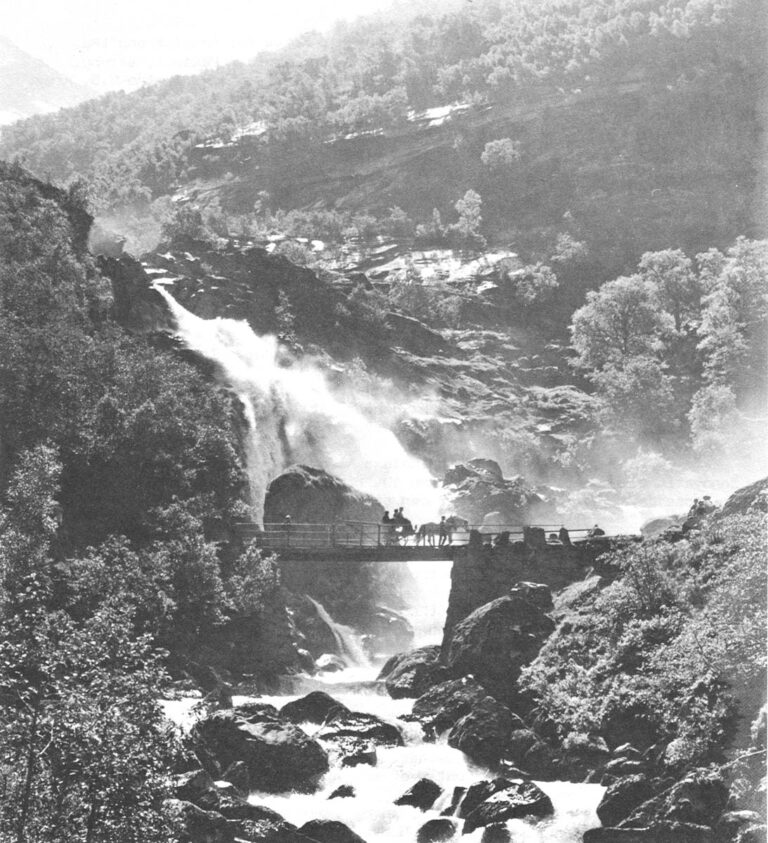

But they came to gape at the landscape, at the largest glacier field in Europe. Then as now, they climbed aboard the fjord pony trap for the trip upward along serpentine trails.

Uncle Bjorn has driven them for 40 years and knows all the stories. And where to find the lavender mountain flowers and white snowdrops growing alongside the pink, white and gray-striped quartz “sidewalk” leading towards the Briksdal glacier.

High in the mountains are the “seter,” the small summer huts where young girls herded sheep and cows and cooked vats of cheese. Nowadays, the seter is a resting-place during long hikes. Also a prized vacation retreat. The villagers claim in all earnestness that they need a second house to get away from all the hustle and bustle of everyday life.

To be alone with nature is to be together with the trolls and nisse. They come in big and little, good and bad shapes and personalities. So they say.

One native of Stryn, now a resident of Seattle, decided to sleep alone in the mountains one spring night and scoffed at the “superstition nonsense.”

As he tells it, he was miles from civilization when he heard a knock on the door in the middle of the night. A bit shaken, he opened the door. No one. Stillness.

A bit later, another knock. And another uneasy look at…black emptiness.

The third knock. Panic. Nothing. Sleeplessness until morning.

“When I stepped outside in the daylight,” he concludes, “I found a huge icicle had broken into three pieces. Each time probably falling against the door.” Probably.

Silly or not, on Christmas Eve some housewives pour a silver tankard of beer around the base of the nearest birch tree. That’s to pacify any evil spirits around the farmhouse.

Children are kept at a safe distance from the river’s edge with the admonishment that the slimy River King is waiting for them in the depths.

But so are a lot of fish, especially in the Stryn River, which boasts the best salmon fishing in Europe. A New York banker has already caught on and built his retirement house there. He also pays out 22,000 dollars a season for exclusive rights to angle those 55-pound beauties.

There is no tradition of pubs or coffeehouses in Norway (the solid drinking was learned at home). But the best food around is at the 11-room, 200 year-old inn in Stryn. Appropriately, it’s called the Walhalla.

Walhalla was also the Viking’s name for paradise where buxom Valkyries would ply them with generous droughts of mead.

At 78, the cheery-faced, redheaded innkeeper, Olena Itrede is a good stand-in for a Valkyrie, but you have to go elsewhere for beer in this dry county.

Naturally, many turn to making their own. Especially at Easter and at Christmas time. Friends call eagerly to sample the new batch, which is poured into gallon-size antique wooden ale bowls. Some are 200 years old and decorated with flowers and naughty ditties.

Of course, there is also aquavit, the liquid fire drunk while eating marinated herring.

As the evening wears on, the wife goes to the “stabbur,” a form of outdoor pantry, for yet another pot of herring, some of the honey-flavored goat cheese, or the “fenelar,” the air-dried leg of mutton.

For centuries, farmers have built a stabbur (a wooden bin on stilts) near the main house. In addition to food, it holds Sunday-best clothes and the hope chest.

Also a lot of memories. One old-timer gets a bit misty-eyed as he recalls courting the farmer’s daughter in the attic of the stabbur where she slept on warm summer nights. “It was a beautiful time,” he says. “Ah, the taste of stolen kisses amidst the smells of drying hams and mutton, sheep’s wool clothing, old wood…”

New houses have their own form of stabbur on the ground floor (where we would put a living room). One corner often has a special room reserved for baking flatbrod. These are the paper-thin, pizza-size rounds of rye crisp, which Norwegians have been eating as a bread staple for centuries.

Older still is the spirit of equality and fellowship. In the absence of serfdom; the Norwegian never needed a word for “sir.” Politeness, regardless of status, is always mutual.

The most effusive greeter in Stryn is Martin Lilliheim, enterprising editor of the local daily Fjordingen. Lilliheim motors about his village in a green Volkswagen and offers old and young a quick, formal, palm-out salute. “It’s a special feeling in the morning,” he says, happily, “to see everyone you know and to greet them.”

The emphasis is on people.

World travelers like Inge Loen Grov come back to Stryn to stay because city life is so vapid. “We do not want to spend all our energy getting things,” she explains.

No one seems to mind the seven-month hibernation in winter. Weaving, knitting and woodcarving occupy the short evenings.

And there’s always a wedding or birthday party to turn out the village.

Then the hardanger fiddler works over his viola-like eight-string instrument. The folk dancing begins. Jacob Myklebust, a tailor by day, forgets he is 92 and solos out for the Hallinge. With the spring of a pole-vaulter, he directs a kick at the hat dangling from a pole. He knocks it off.

“I won two Hallinge championships,” he says proudly, “kicked almost seven feet high.” The man radiates vitality and involvement in life.

(One learns his age by chance. No one bothers about such things in Stryn because there is no marked distinction between adults and older adults.)

Myklebust continues to describe his talents as a speed skater on ice. Also as violinist and composer.

One of his waltzes was featured at the new community center recently. Occasion was the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the newly arrived concert grand. All the villagers had contributed to buy it as they had the center itself.

The program offered an 18-piece brass band, 18-man string orchestra, two choruses and many soloists. All good. All of Stryn.

After the speeches, the jokes, the raffle to earn money for the new swimming pool, the concert, the whole family (including great grandmother) stayed for the dancing. It was polka and the Rhinelander until the wee hours.

An exhilarated Lilliheim says, “These are my people. This is home. This is what ‘How Green Was My Valley’ is all about.”

Stryn, he adds, “means ‘the place where it is good to live’. With a wry chortle, he says, “It also was once the home of the meanest Vikings.”

Nowadays the extra adrenaline is used to make buses, furniture and clothing. In the last five years, the community has brought in small industries to encourage youth to stay.

Elsewhere throughout Norway, approximately 15 to 20 farms are abandoned daily.

Vikings and Odelslov aside, young men are deserting the countryside for the economic security of a factory wage elsewhere.

Ottar Starheim, a neighboring villager, calls it a “silent struggle” and despairs of the outcome.

“My son,” he explains, gnarled fingers deftly finishing a roll-your-own cigarette, “milks the cows and feeds the sheep before he leaves for the factory in the morning.

“At night, after he returns, he is tired but must again feed the animals. When will he find the time to get the hay and fertilize the land?

“What will he choose later on? Certainly not farming.

“We are just standing at the door,” continues the old gentlemen, rubbing the sleeve of his patterned, hand knit sweater (from his sheep). “The Common Market commissioners in Brussels say there is only room for larger farms. Ours is just a few acres.

“That’s my son’s dilemma. He knows what he will get in the factory plus social security. If he remains on the farm, he cannot do it alone.”

Sadly he sighs, “My father and grandfather struggled and gave all their heart and energy to keep the farm. Now it is going down. Our heart’s blood is in these stones.”

So is an unwritten allegiance of son to father.

In the pre-pension days, under the custom of “kar,” the son left the old house to his parents and built his new one next-door or adjoining. He also gave over a few goats, a cow and other provisions.

Through the pension, the father is now self-sufficient. But the emotional ties remain. Even today one builds “next door.”

Lilliheim’s house is attached to that of his father, a widower, 83. (He, too, had once lived in Fargo, North Dakota, had bossed a crew of Bulgarian railroad workers and served with Uncle Sam.)

“We wouldn’t dream of living elsewhere,” says Lilliheim. “There is only one door between us and it is always open.

“My father enjoys television and comes over every night to sit and watch. But most of the time, my two boys are with him in his house. They like it there more than at home.

“It reminds me of my own boyhood,” he continues, a pleased smile of reminiscence coming to his face. “Every Christmas Eve to this day, we have dinner in the old house. I’ve only missed two.”

His voice tightens a bit as he adds, “I wouldn’t take 10,000 kroner to miss being at home for Christmas. Not for the fanciest party with dancing and all.

“This is a part of life,” he concludes. “My sense of belonging.”

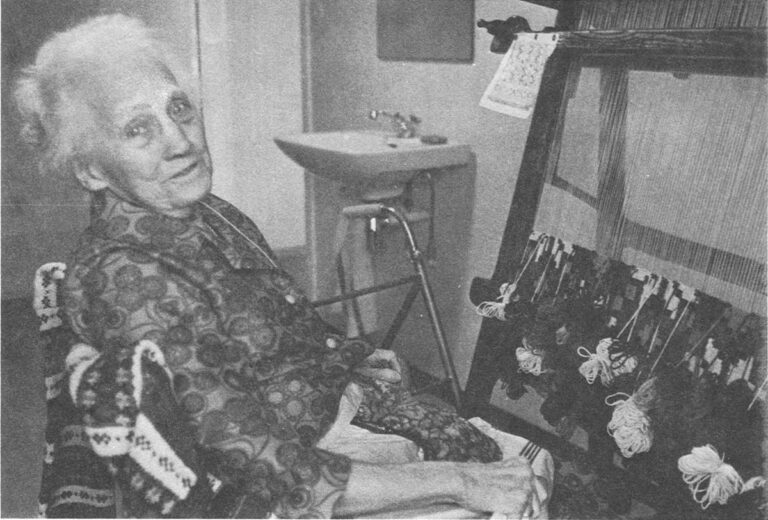

Berggot Ovre-Edie also lives a stone’s throw from her daughter at the edge of a lake.

The proximity means constant visiting by her grandchildren. Also a hand when her arthritis takes a turn for the worse.

Despite her affliction, which confines her to a chair, Mrs. Ovre-Edie, works a few hours daily at her loom.

A Stryn native and nearing 70, she is known throughout Norway and in the art world, for her exquisite hand-loomed tapestries.

They depict legends and fairytales, and religious symbols. A few are copies of intricate 12th century abstract designs.

She grows and spins her own wool. And dyes it with grass and leaves to get the unique, earthy colors.

Mrs. Ovre-Edie, despite the acclaim, is modest about her accomplishments. Of her self-taught talent, she says, humbly, “My inspiration is from God. I do what I can.”

Other inhabitants of this valley are also favored by the muses. The local tourist shop offers a good selection of clothing articles and household accessories knit, woven, embroidered, painted, carved, tanned or welded by part-time craftsmen.

Edmund Langeland, 62, turns out 2500 beer mugs, milk bowls and butter pots a year. The aromatic juniper wood from which they are formed grows in his back yard. It all began as a hobby but turned into a livelihood when he had a heart attack five years back.

Oscar Garland is too busy traveling to work.

At age 92 he doesn’t have to bother.

After eking-out an existence on a mountain precipice for most of his life, he has done his share of physical labor. His son, age 61 (and looking like a wiry 45) is now in charge.

As did his father and generation back, he grows hay on the slanting, rocky land, raises goats and lambs, and daily expedites goat milk via private funicular.

Until a few months ago the Garlands had to scale the 300 meters on foot. Winter and summer. Going down when ice formed was especially difficult during the school years they recall. Often the father had to dig out a footpath first, then precede the youngster down.

Now, thanks to the community fathers, there is a road. Knut Mork, mayor of Stryn, says it cost 60,000 dollars.

American logic would demand, “Why spend all that money on two families, a total of seven people, when they could just as easily move down?”

Mork quickly retorts, “But this is their home. This is their land.

“Why should they move?”

One never did catch up with grandfather Garland. When last seen, the agile retiree was off on a six-hour climb to the next mountain. To say “hello” to a friend.

They say Norwegians live forever.

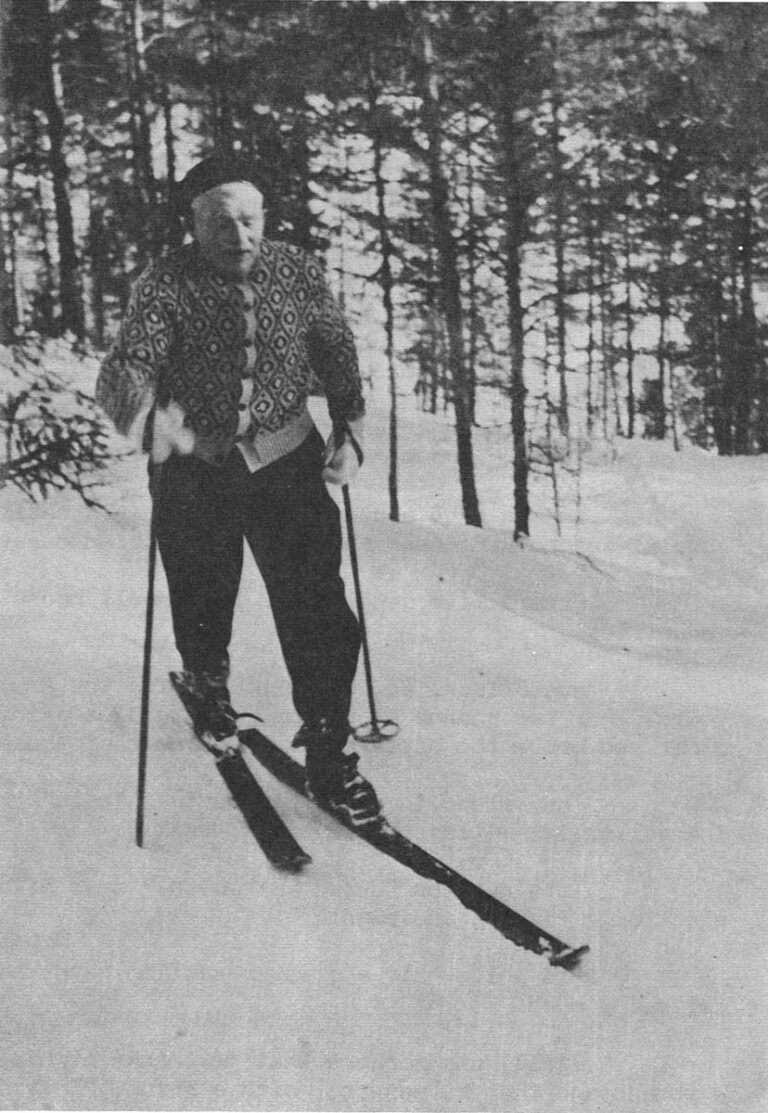

Convinced of it, Lars Dybevoll, at 90, is an avid skier.

Birthdays don’t matter. Activity does.

As long as a man can hoist a glass, ski, fish, farm, dance and tell a good story all those things or one he is part of the group.

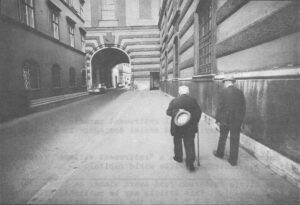

When physical aging does set in. When one is no longer able to manage alone in home surroundings, drastic changes take place.

The community tries to send in home-aides and visiting nurses as long as roads remain open in summer. But it is still two hours and 28 miles away to the nearest emergency hospital.

Therefore, the lone elderly are often forced out of their homes (sometimes with the aide of the sheriff) and put into the nearest home for the aged where they can be cared for. Alas, “near” may mean 20 miles from the home village, an enormous distance for relatives to visit.

Some patients never adjust to the new surroundings. After years of outdoor living, miles from another being, they are suddenly stuffed into tiny cubicles with total strangers.

“Many prefer being lonely to being crowded into a small home,” concedes Dr. Arne Boyum, a local dentist and head of the health council.

In the Stryn home for the aged, eight men (looking 20 years younger than their eighty-plus years) are wearing the typical gray ski sweaters. Supper consists of platters of open-faced sandwiches and mugs of coffee.

“Are you from Minnesota?” asks one of them. He, too, had had his U.S. fling as a railroader.

In her own room, a spinster, 85, points proudly to her “tea kitchen” and furniture. Also to a decoration from the late king for 40 years of service as a health inspector in Bergen. Now she is home again.

Local officials estimate one-third of the native born eventually return to retire. But a better housing alternative, says Dr. Boyum, is to build small cottages around a nursing home. Retirees pay 80 per cent of the building cost, the government the rest.

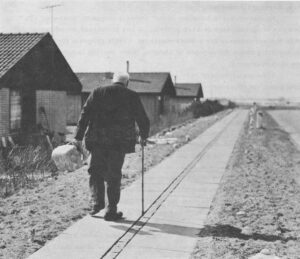

Seamen have another attitude toward retirement. Some enter special seamen’s homes, which dot the Norwegian coastline.

Others live generations in a small house somewhere near the fishing industries.

Jon Silden, 46, has been roaming the Arctic waters for more than 30 years. For two months at a time, on the blue-painted “Sildoy,” he and eight other men brave the bitter cold in pursuit of the prized cod.

They sleep in wall nitches in a “hole” the size of a king-sized bed. The galley is smaller than a school desk.

It’s not the “Queen Elizabeth,” says Silden, “but it has the necessary electronic fishing equipment.”

His white hair and water-swollen hands belie his age and he doesn’t talk very much.

Still, one wonders what he thinks of his job. His blue eyes flicker a moment and then he answers, with a shrug, “I myself have no choice. This is my life.

“But since nine men of our island went down at Christmas time (a family of four brothers and two sons), I wouldn’t want my son to do it.”

For the moment, son Per, 9, is fascinated with the far off places and runs to show off the family album of neatly pasted postcards. All from his father’s fishing expeditions.

He also listens attentively as grandfather Silden talks about the old adventures.

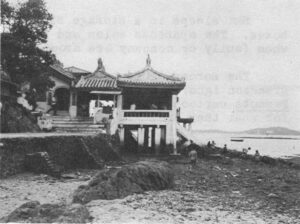

The two generations live almost side-by-side on the small, treeless island of Silda. It is located near the fish-processing town of Maloy at the mouth of the Nordfjord. There are only 30 families and all live from the sea. There are no cars, many rocks, two barns for drying fishing nets, and a general store in the basement of a private dwelling.

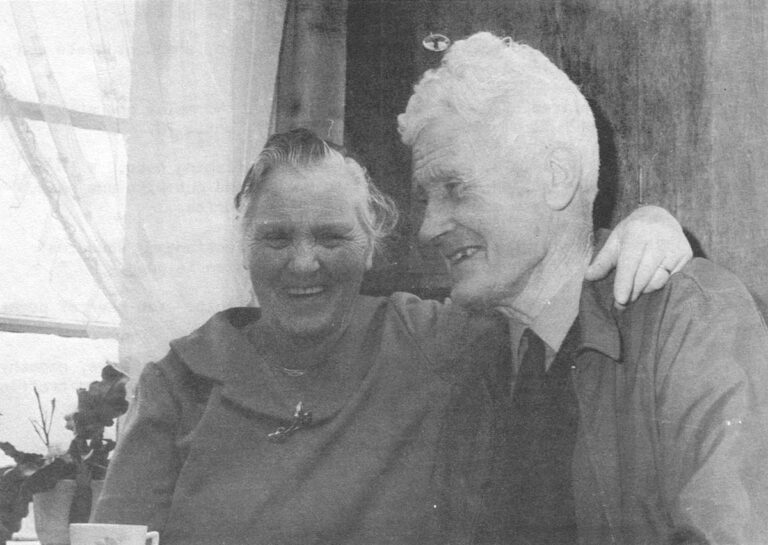

Fritjof Silden, 75, and his wife, Lovise, 69, live in the reddest and oldest house on the island.

“In winter,” says the jolly-faced Mrs. Silden, as she quickly prepares a festive tea table, “it looks like a Christmas card.”

Pink and red begonias line the white-painted windowsills and sea gulls arrive eagerly at the outer ledge for lunch.

Furnishings are sparse and modest. But the ambiance is cozy and inviting.

Much of it reflects the geniality of the hostess. She is visibly excited that anyone would come so far (40 minutes by speedboat) to visit.

On her best linen tablecloth she sets down platters of decorative sandwiches and the sweet cold waffles which Norwegians relish with gobs of fresh butter and orange marmalade.

Slowly, shyly, after a bit of good-natured joking and teasing, the older Silden reflects on his lifetime. “I started to fish at 15,” he says, “as did my father. I could also have chosen farming or gone to the U.S.

“Fishing is hard work (you don’t sleep for days on end when the catch is in), but now there are good boats. Yes I would do it all over again.”

Mrs. Silden shakes her head. “I would have preferred to have had him at home,” she says. With her right fist she taps her chest adding, “I used to worry constantly.”

To keep busy and earn some money in those days, she kept goats and lambs and spun her own wool.

Silden retired at 62 because of a bad foot. Normally one stays on until 65 to get the full pension; others in industry until 70.

True to his skills, he continues to repair fishing nets. With a quick twist of the wrist, he demonstrates how to tie and cut with one hand. He also tinkers with scale model boats powered by batteries.

“Life is rich,” says Mrs. Silden, as she affect affectionately squeezes her husband’s hand. “We have good health and the pension is good.

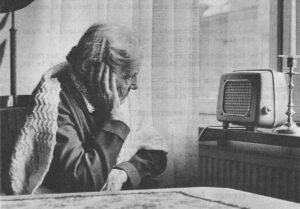

“In the city,” she adds, “life is more difficult. You hear of people dying and not being discovered for a week.

“There is no room for the elderly in the cities,” she says, empathy welling in her kind, gray eyes. “They are in the way as the tempo and traffic beats around them.

“Here,” she continues, spreading her arms outwards, “I am free. I can be myself and go about and do as I wish.

“No, I don’t think about growing old,” she concludes with a hearty laugh. “I have too much to do and see before then. But when I am old, I think it would be nice to be here at home.”

The fishermen of Silda and the farmers of Stryn are good examples of what anthropologist’s term ideal aging: To grow old in stable cultures where one still has a function.

Kari Mannsacker of Norwegian television documented the lives of the elderly Norwegians and concurs; “It’s better to be old in the country. The money comes out better too.

“They have always had a hard life and are less demanding and expect less from life. They accept their lot and never ask for anything,” she says.

In contrast, Mrs. Mannsacker criticizes urban pressures and neglect.

In Oslo, she found half of the housing facilities consisted of cold-water flats with outdoor toilets.

“How can one care for the blind and the infirm aged in such uncomfortable places?” she asks. “Added to the normal problems are those of heating during the long, extremely cold winters.”

Jorunn Johnsen, of the daily Aftenposten, in Oslo, derides “the inadequacies of the welfare state.

“It should provide,” she says, “for those who in early time laid the ground for our present standard of living. Instead they allow some to freeze. There are too many such instances.

“I am ashamed of it.”

Annually near Christmas time, Aftenposten sponsors “Operation Wood.” Contributions average about 21,000 dollars and are used to purchase firewood for the needy aged.

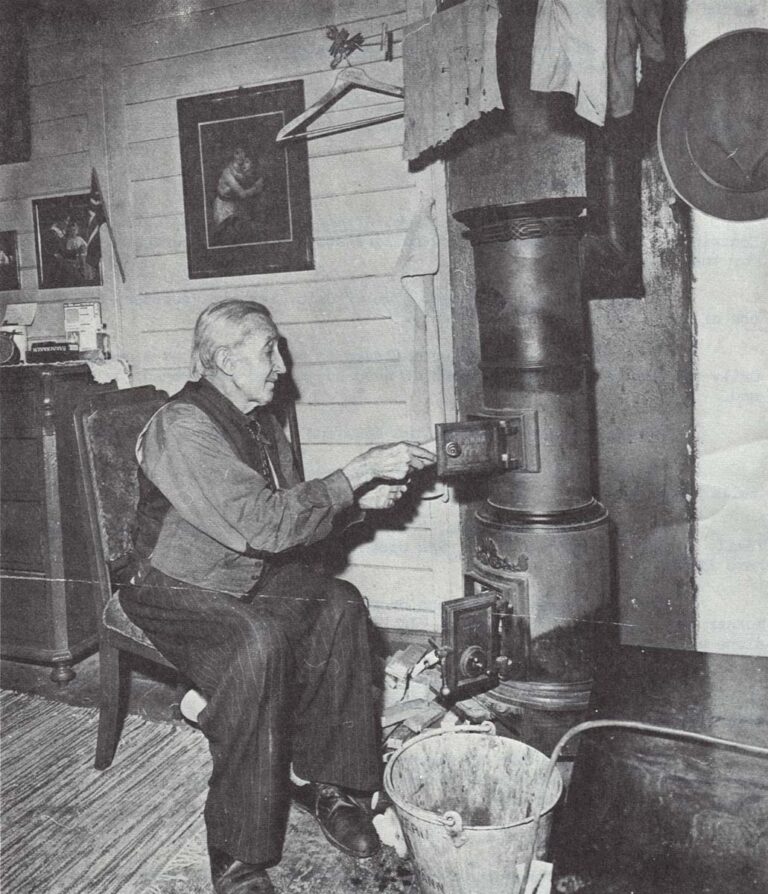

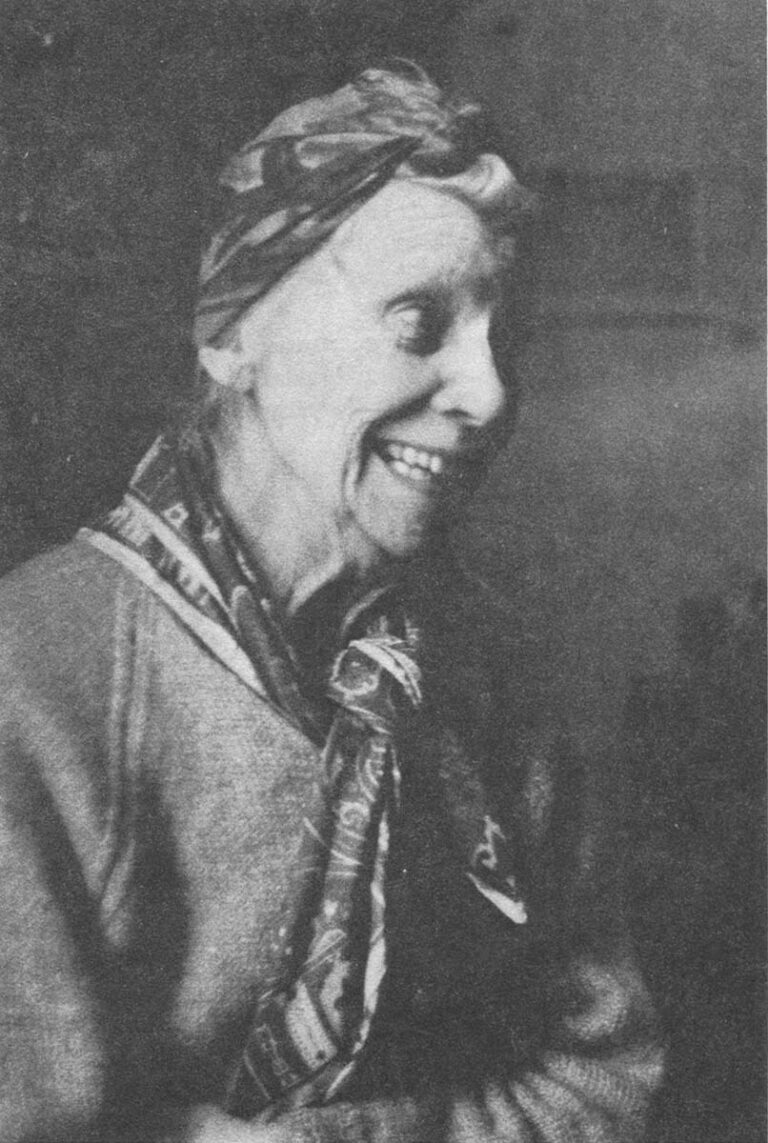

In the unfashionable east side of Oslo, Kaspara Pedersen, 87, lives in one of those damp, chilly apartments.

A widow, she raised five children on money earned as a washerwoman. Daily she had to carry heavy loads of wood and washed and ironed for hours on end.

During the war, she lost two sons and still mourns for them.

“I have done all my crying,” she says with a bright smile as she tells her story.

“My daughter,” she adds, “with her lovely apartment, good job and family is not as happy as I am. She doesn’t know what it means to have had a hard life.”

The middle-aged blond, who drops in often to visit, agrees. “My mother never complains,” she says. In her own way she is content. To be alone and with her memories.

“She is forever giving encouragement to others,” she adds. “She has never coveted status symbols or anything for herself. But she is proud to have been a beauty.”

Amused at the turn in conversation, “Mrs. Pedersen pulls the thin gray sweater tightly about her, preens coquettishly, and chortles, “I am still tall. Am I not still pretty?

The smile never fades.

Others with fewer inner resources and dependent on external services have difficulties in adjusting to retired life.

Compared to neighboring Denmark and Sweden, Norway is a poor stepsister in developing services for the aged.

Pensions and home services lag far behind and good nursing home institutions are few and far between say official spokesmen.

Services vary greatly between municipalities as well.

“Until 10 years ago,” says Dr. Torbjorn Mork, secretary of state for health affairs, “There was too little emphasis on old people.

“The interest was in the young. The old became a lost generation.

“Media and concerned persons finally reminded us that here was a group lagging behind economically and otherwise.

“It’s still a low income group with the problems of a low income group,” he concludes.

The Norwegian Pensioners’ Organization, with a labor-union-based membership of 35,000, is pressuring for better pension benefits.

By 1973, it also hopes to have convinced Parliament into lowering the retirement age from 70 to 67 as it is elsewhere in Scandinavia.

Opponents say the country needs the elderly manpower. Also that it cannot afford the extra pension expenditure of approximately 84 million dollars.

“It’s a matter of priorities,” says Mork. He also mentioned high costs of defense as more pressing.

As in the U.S., work in Norway is tied-up with identity.

“For some, ” says Wenche Margrethe Myhre,” editor of “Mid-day Hours,” a radio program for the aged, “work is their only source of importance.

“Listeners tell me it’s not for the money but to have meaning to life.

“Hobbies are not enough,” she adds. “And hobber centers in Oslo (sponsored by the public health association), somewhat unnatural.

“Few attend them,” she says. Youth sings to them, but doesn’t converse with them. Then they say, ‘Isn’t it fantastic what they do for us?’

Mrs. Myhre’s young face crinkles together in anger. “Those elderly souls should say they hate the place but need it. That it is something to do. There are a few men and many women. I guess in a way they are at least together.”

The newest club or so-called day center is Majorstuen. It is located in the 200 year-old birthplace of Norwegian painter Amaldus Nielsen. Only 20 persons can fit in so “membership” is by doctor’s referral only.

The director tries to get them involved with handicraft and each other. But for many, as elsewhere in the city, the primary attraction is the tub for a weekly bath, and a hair set or pedicure for less than a dollar.

At Baerum, seven miles outside Oslo on the Oslofjord, is Rykkin, a new, 27-patient nursing home. It is located near the Sonja Henie cultural center and is considered a model for future Norwegian aged institutions.

The innovation is partly architectural: The institution is built on the ground floor of a huge apartment complex. The hope was to integrate the aged with the young families in the building. But many of the patients are too old or bedfast.

The staff is proudest of a separate room for sterilizing bedpans. Also a craft room where a few ladies thread beads but never speak with one another.

There is no cozy, central lounge where people can meet and talk or be near one another. A few uncomfortable contemporary chairs here and there along the corridor suggest a bus stop more than a home.

Older homes in this area of Baerum, the richest suburb in Norway, have the homey touches. But in one, smoking is restricted to one room and the beloved beer is prohibited. The photo of the donor shipbuilder hangs in the dining room and the Saturday evening diversion consists of a sermon by the local pastor.

At the newer Rykkin, the Jens Eriksens, are allowed a few photo mementos and a settee alongside the twin hospital beds. Ragna Eriksen, 88, also has her loom in a spare room.

She sits working on a rug design and in beautiful English (learned during school years in Cheshire at age 19) recalls international neighbors and trips abroad.

“We finally came here,” she says, “because home help was available only two days a week.

She tells more of English friends and then pauses as tears well up in her eyes. “I wish I could be home again,” she sobs. “They are very kind here, but… “

Rykkin was built after much debate among health officials. Their greatest concern centered on the reaction of the children. “How will they feel,” demanded one participant, “in seeing funeral vans in front of the building?”

The folk in the country is fatalistic and accepting of life (long) and death. However, city people, at least in Oslo, ignore death and refuse to speak about it. “We constantly deny death,” says Mrs. Myhre.

“I try to bring it out in the radio interviews, but the elderly refuse to think about it or talk about it. They romanticize it and avoid using the word. They call it ‘the evening of life’.”

Dr. Igip Vorg, a psychiatrist, says it’s tied in with the wish to continue the long life they know exists here.

“Of course they live forever here,” says one U.S. Embassy diplomat. “They know how to take life easy.” (In summer, for example, everyone is out of work by 3:30 so he can go sailing or walking.)

“They ski until they are past 80 and get in their saunas.

“There is no real competitive push here. They relax. None of that GNP reverence we have in the States.

“I figure,” he concludes, “for each year I’m here, I am adding one year to my life span.”

Endit

Received in New York on June 23, 1971.

©1971 Nada Skerly

Nada Skerly is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. This article may be published with credit to Miss Skerly, The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star and the Alicia Patterson Fund.