The telephone jangles in the study of the bishop of Stockholm. He answers it with a business-like, “Hello, Bishop Ström here.”

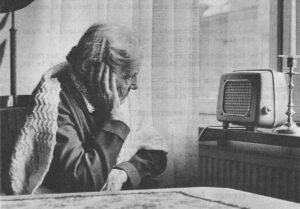

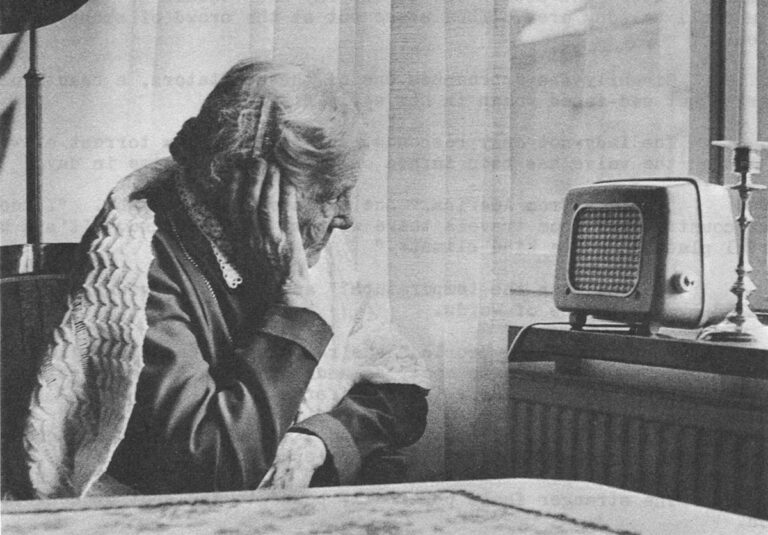

“Oh, I’m sorry,” says the caller, in an elderly, disappointed voice, “I have the wrong number.” A second’s hesitation, then the words tumble out in a forlorn plea: “For heaven’s sakes, don’t hang up. I haven’t heard a human voice in two weeks.”

Isolation.

This is Stockholm.

An American journalist walks into N.K., Sweden’s largest department store and sees a row of elderly individuals sitting off in a small balcony area. They stare out at the crowd of shoppers. Silently.

Gingerly she approaches one of the spectators, a beautifully dressed but sad-faced woman in her early sixties.

The lady not only responds, but spills out a torrent of words. As though the valve has been turned on for the first time in days.

“You are from America,” she exclaims with delight. “I know your country well from travels there with my late husband. It’s a wonderful place. Such a kind climate.”

“Do you mean the temperature?” asks the interviewer, a bit puzzled by the choice of words.

“No, I mean the people,” she responds animatedly. “They are so warm and open, so nice to meet, so understanding and easy-going. I miss America so much. Here it is different.

“Could we chat a bit?” she adds. “Would you like to come for lunch? When could we meet? Will you telephone?”

The stranger fools physically bound to the spot by conversation.

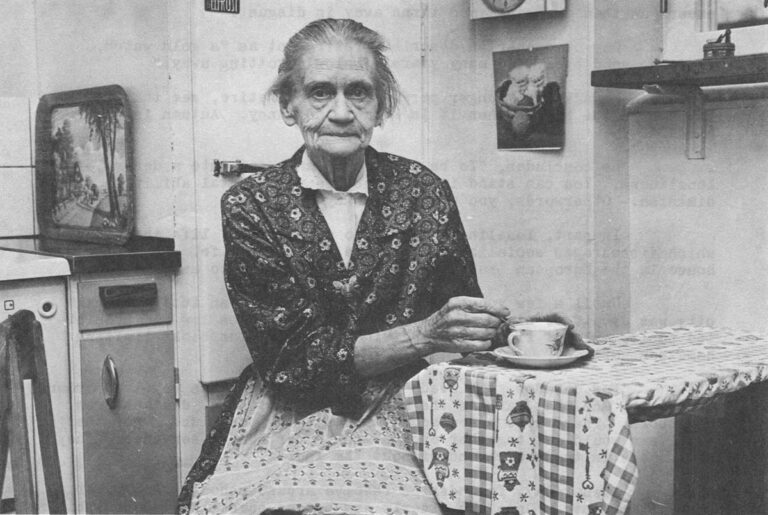

Over a cup of coffee in the store’s tearoom, she talks of loneliness. Of divorced, unhappy children. Of friends who have died and the dearth of new ones.

At parting she says brightly, “Thank you so much. It meant so much to talk with you. May I have your address? At least to send a Christmas card?

Starved for conversation.

This is Stockholm.

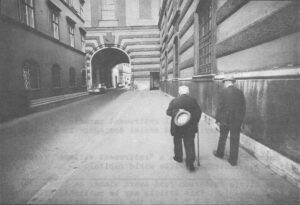

Individuals walk down the busy shopping streets seemingly unaware of one another. Eyes front. One doesn’t address strangers. Be self-sufficient.

An exchange student from Turkey, who drives a taxi part-time, sourly dubs it the Cassius Clay complex.

“Swedes think,” he says, “they are the greatest.”

If you need people, if you want company, buy a dog.

Reportedly Stockholm has one of the highest per capita dog populations.

Some 25,000 pups, pedigree and mutts, are “man’s best friend.”

Sometimes, his only friend.

“Elsewhere,” says one observer; “some older persons would consider a pet a nuisance. Here, it is often a necessity.”

Kirsten Linde, a kennel owner, agrees. She does a brisk business in dogs priced from 140 dollars down to 30 dollars. Irish wolfhounds sell best. Beagles and noodles, next.

Without further prompting Mrs. Linde espouses the salubrious effects of dog ownership. “It is essential,” she says, “for the elderly to have a dog.

Without further prompting Mrs. Linde espouses the salubrious effects of dog ownership. “It is essential,” she says, “for the elderly to have a dog.

“It’s an alternative to sending them to a nursing home where they will die.

“With a dog, they have something to live for. It takes them out of the apartment and gives them something to care for.

“It also saves money for the state,” she adds. “Cuts down the cost of institutionalization. More apartment houses should allow dogs in. It saves lives.”

Life in Stockholm.

A heart attack victim is being released from a large metropolitan hospital. “Do you have any family?” the patient is asked. “Yes, I have two children, but I haven’t seen them in years,” she replies matter-of-factly.

The attending physician nods his head wearily. He has seen many such cases. “It is horrible to be sick or old here,” he says.

This is Stockholm.

There are eight million Swedes. About 13.5 per cent of them are over 65.

They are a blemish on an other words perfect social welfare model. A group that doesn’t quite fit into the mold.

Leif Carlsson, an editor of the Stokholm daily, Svenska Dagbladet, broods, “The aged are our most serious social problem.

“It’s not an economic one,” he adds, “but one of loneliness.

“They live without human contact.

“We flatter ourselves,” he continues, in a flat, unemotional tone, “to think we’ve solved it with economic means. Economically, the aged are better off here than in the rest of Europe. But no one is really taking care of them.

“As William Faulkner days, we pay too much attention to facts and too little to circumstances.

“We create plans and systems,” Carlsson says, “but we have institutionalized forms of Christian love. We are building a modern, efficient society of steel and concrete. One devoid of tenderness, caring and love. Personal engagement is missing.

He concludes, “We don’t like to see direct human contact. It makes us uncomfortable.”

In Sweden, aging is described as the “first death.”

Not physically, but socially.

To be old is to be out – in a society, which values productivity and youth as much as Americans do. “It’s frightening to contemplate aging here,” says a middle-aged researcher. “You’re stamped out of life at 65.”

Lars Ulvenstam, producer of numerous programs about retired life for Swedish television, says, “Individuals try to escape aging through a hysterical vitality culture.”

Everyone gets out for “orientation” on Sundays. It’s an exercise marathon of walking and climbing to keep fit. Many business offices keep a walking chart near the water cooler and employees are honor bound to record the kilometers.

Ulvenstam finds it overdone with a plethora of radio exercise programs for the elderly with “idiotically fresh and energetic dance tunes.

“It is inverted and degrading,” he adds. “No wonder youth sneers at them as ‘gaga’ and turns away in disgust.”

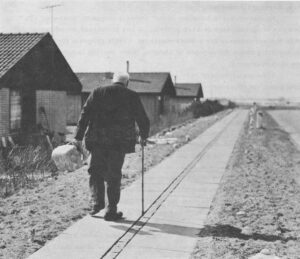

One octogenarian describes retirement as “a gold watch, flowers, good-byes, and many years of slowly rotting away.”

He advises younger persons, “If you retire, see that it happens in the spring when it is bright and sunny. Autumn is too harsh.”

He concludes, “To be old, is to walk out into a desert of loneliness. You can stand it only because your mental abilities also diminish. Other words you would go crazy.”

In part, loneliness is due to a pattern of life in Sweden, which discourages socialization. There is no pub life. No coffee house in the European tradition where one could go to meet people.

In part, loneliness is due to a pattern of life in Sweden, which discourages socialization. There is no pub life. No coffee house in the European tradition where one could go to meet people.

Until a few years ago, even Stockholm as an international city was devoid of nightspots. A strict temperance law had prohibited public sale of liquor and individuals had ration books limiting home consumption.

For decades, the Swede’s entire existence has revolved around the home. One that was, in the majority of instances, distant from, neighbors. There were a few good templar religious clubs. For the rest, men would get together once a week, after Sunday services. They would meet in the church and without the ladies.

Even today, friendships revolve around school, family, or work attachments. Once the elderly are beyond these limited possibilities, there are few acceptable means of meeting new people.

Stories proliferate about Swedish timidity and shyness. There’s one about the desert island inhabited by two Danes, two Norwegians and two Swedes. After a year, the Danes had a thriving farm together, the Norwegians were always bickering, and the Swedes were still waiting to be introduced.

Knowing another’s status is the crucial point. In this rigid social structure, plumbers and professors neither mix nor meet. Thus, on an around-the-world freighter, so the tale goes, two Swedes were afraid to communicate. Neither knew the other’s title. Finally, in desperation, one finally broke the ice by blurting out, “Hello, Mr. Passenger.”

An American diplomat tells of walking his dog on the same street amidst the same fellow dog owners. Five years passed without a solitary greeting. The day before his departure for another post, one person ventured to say, “What a nice dog you have,” then walked on.

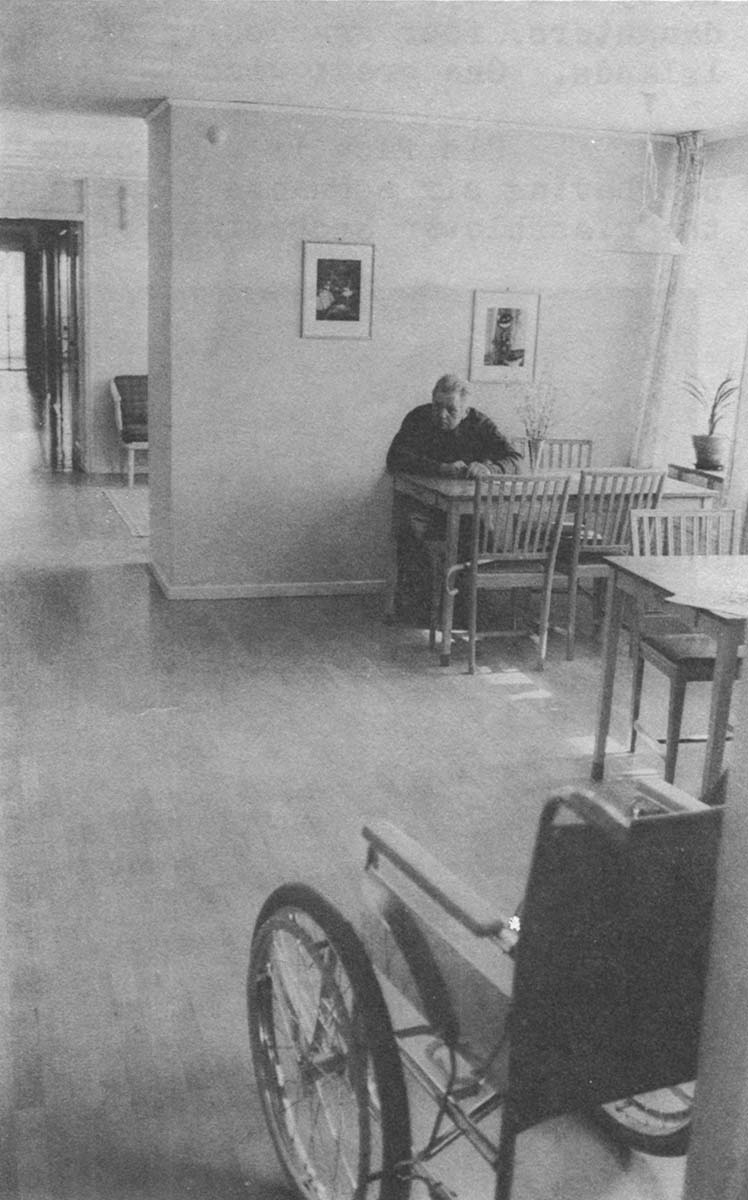

In light of such formality, one can sympathize with the discomfort the aged feel in being dumped together in a nursing home or hobby club situation.

One sees the dilemma at Sirius, a modern activity center in Stockholm for the elderly and handicapped. Individuals sit and work together in silence.

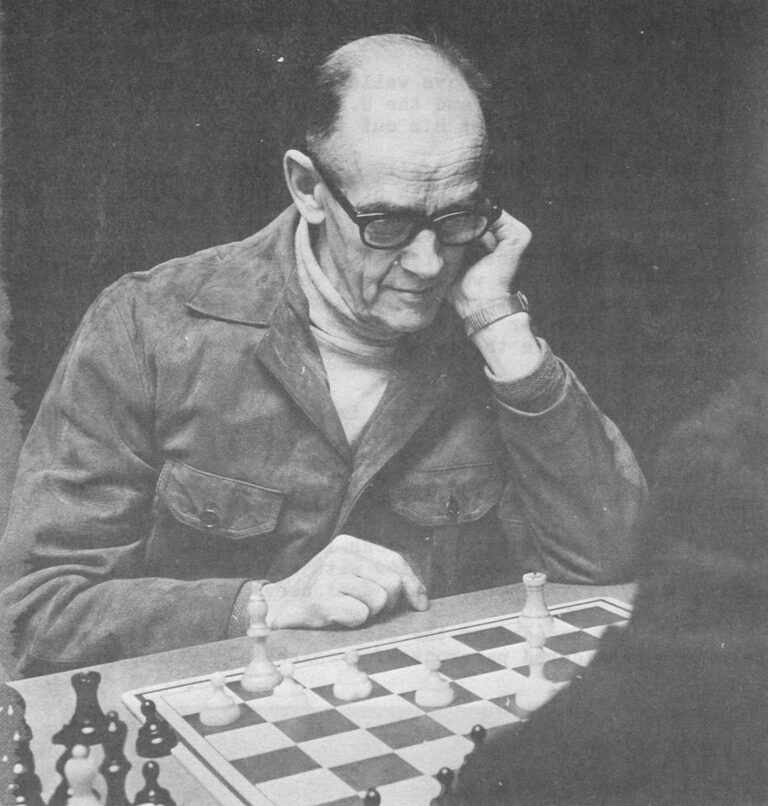

Ivar Forsberg, 82, concentrates on making a wooden trivet. It’s one way to pass the time of day, since, as he says, “There’s no one to talk with.”

Three years ago he retired from international sales position with a textile firm. Fluent in several languages, he’s accustomed to traveling and to meeting foreigners.

Forsberg eagerly shows wallet-size photographs of granddaughters settled in Canada and the U.S. Occasionally, he adds, a daughter in Stockholm invites him out for a drive.

He visits the center daily. Sometimes to play chess. But mostly he finds himself alone with his interests in music, art and books.

One feels compassion for this handsome man, elegantly clad in a brown tweed suit. He would make a wonderful grandfather and/or friend. He offers the interviewer a cup of coffee from the cafeteria line, saying, “A cavalier could do no less. Thank you for the talk,” he adds, as he bows from the waist and kisses the hand in a courtly, good-bye gesture.

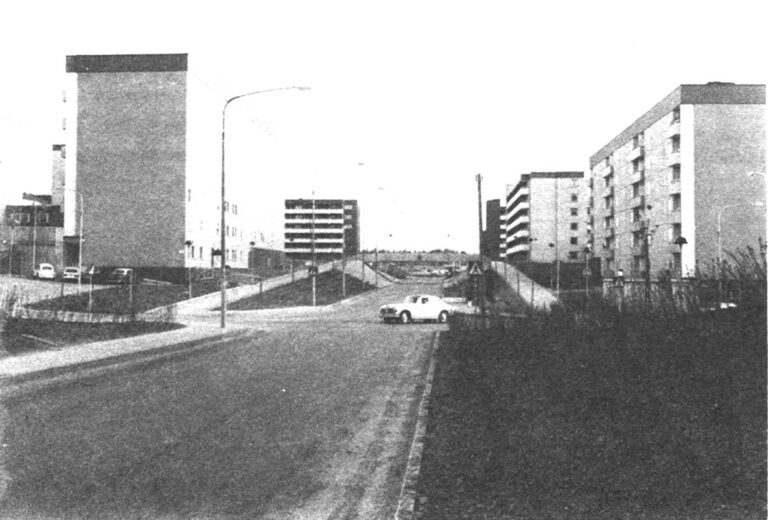

City loneliness also stems from being banished to the “mountains.”

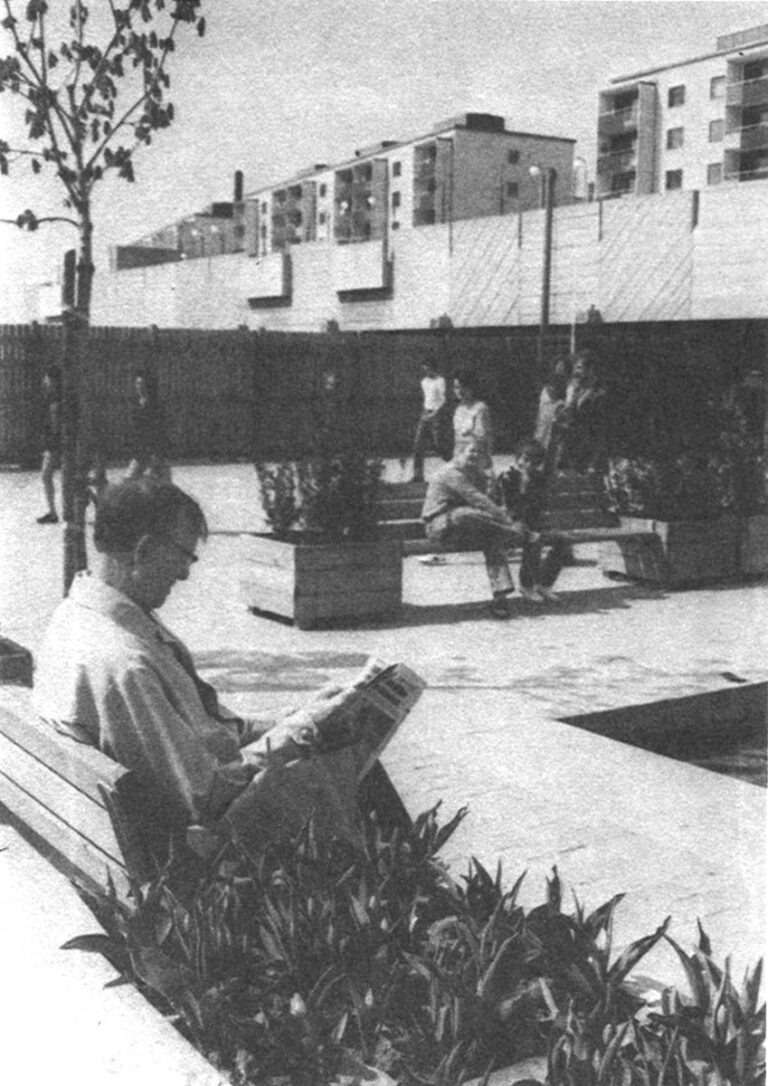

Concrete “mountains” of Stockholm

That’s what one sociologist terms the acres of high-rise apartment buildings encircling Stockholm.

From the air, the city looks like a well-ordered village of plastic building blocks – some yellow with red roofs, the newer ones resembling slim, gray-topped, white dominoes.

It’s the paradox of the old in new suburbs, in slick satellite cities considered paragons of Swedish town planning.

“Except.” says a Swedish diplomat sarcastically; “The architects forgot the human element. Progress is related to economic and not human or spiritual needs.”

Tensta, the newest and largest such development, is considered the most serious drawing board mistake.

Rows upon rows of 20-story buildings were planted in open farm country miles from the center of Stockholm. About 70,000 inhabitants are now stranded without a shopping area, without so much as a snack bar or newsstand. There’s no direct transportation into the city. The only alternative to an 80-minute bus ride is a 30-minute, seven-dollar taxi ride.

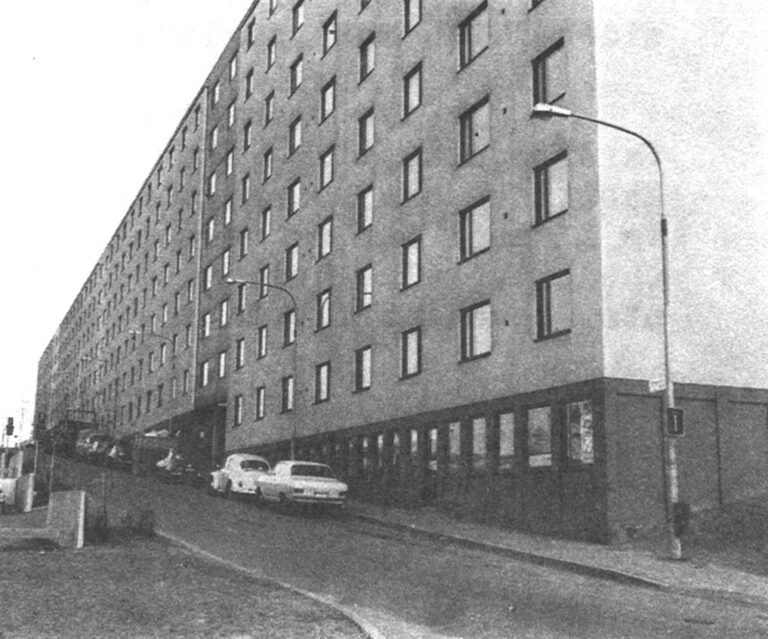

In suburban Skärholmen, Nestor and Stina Dahlstrom have the convenience of both shopping and a direct 20-minute subway ride into the city.

Skärholmen, Nestor and Stina Dahlstrom

Their well-appointed, three-room flat is one of 180 in a building exclusively designed for the aged.

But the Dahlstroms make little use of the subway. Like their friends, they dread the emaciated hippie culture, which prowls the underground, stations and robs and terrorizes.

As for location, their balcony faces the Singer sewing store and a polluted water fountain. The “lawn” is miles of concrete sidewalk. There’s a small garden at the apartment entrance, but despite the warm, sunny weather, no one sits in it.

Because rentals are exorbitant (averaging 120 dollars a month), the state subsidizes 40 per cent of the dwellings. For the elderly and families alike.

Kay Pollack, a playwright, says, “The elderly are thought to have everything because the pension is good and they have a modern kitchen and a room.” (At age 67, the retiree gets approximately 60 per cent of his former peak earnings.)

“So,” continues Pollack, “relatives ignore them and neighbors don’t care. Everyone is busy with his own life.”

(Ulvenstam derides the “frosty heaven of the welfare state which takes away the desire for individual philanthropy.”)

Pollack understands the plight of the aged after months of research. Initially, for a documentary on Stockholm in general. But at every turn he found the lonely old.

The result was a 50-minute commentary in drama form called “Flag of Security.” It is a brutal, candid portrait of human misery confined within walls of concrete and glass.

The would-be hero, Gunnar Roth a stocky, good-natured laborer, peers up through binoculars at the thousands of windows of an apartment complex. He worries that the old-timers within could “lie down and die without anyone knowing it.”

He decides to make flags for security, which each individual could place in his window. Horizontal stripes facing outward would mean, “I’m O.K.” The wavy side out, “help.”

Gunnar paints and distributes them himself, then each day hops on his bicycle to check the flags and the condition of his old friends.

Soon he has more requests than he can handle alone and a glib entrepreneur suggests they organize the service together. It becomes The Home Security Corp., complete with advertising campaign and mini-skirted hostesses. When Gunnar protests, he is eased out of the scheme. The new president jokes about the “damn funny old ladies” he sees.

Pollack succeeds in showing how an altruistic idea gets exploited for profit. Translate: The Peter Principle in Sweden, where one becomes so preoccupied with organization that one loses track of the original purpose.

The mania for organization is not a Pollack innovation. Critics describe Sweden as a “system of sterile, beautifully clean conditions devoid of soul.” The human element is missing.

In theory, the systems are impressive. To reach the aged in rural areas, the government has devised a mobile unit equipped with house cleaning, laundry and meal services, plus a librarian, chiropodist and hairdresser.

The state also pays for “home Samaritans,” a family member to stay home and care for his older relative. There is a core of professional visitors and a “big brother” system in each municipality to check on the needs of each retiree.

In practice, the exquisite models break down. The individual seems to rebel against computerized care. For example, the telephone buddy system, just taking hold in a few U.S. communities, is well established here. A lonely older person is telephoned at the same hour each day as a check on his health.

“But that is being controlled by an organization,” Pollack laments. “It’s a bad solution. All one hears is a voice organized by society. Thus relatives are free because an official controls their parent. It only accentuates the loneliness.”

Another community boasts a toilet-flush system to check on the loners. Each apartment toilet is equipped with an alarm, which sounds off in the basement if the toilet is not flushed at least once every 24 hours. The janitor then alerts the emergency squad.

Some crafty old-timers beat the system by using a neighbor’s facilities. Then when the alert sounds and someone comes up, they can have a nice chat.

Margareta Harlin, an administrator at the Social Welfare Ministry decries the loopholes in the system. Most of her day is taken up with persons who “call and cry and just want to talk.”

She says, “Somehow we haven’t faced the real problem. We give them handicrafts and services instead of asking them their needs. We should not organize for but with. We shouldn’t reprimand them if they don’t want to sew or weave. We must change our thinking.

“How can society organize the inner life?”

Ulvenstam is pessimistic about injecting non-materialistic values. “The mentality of competition,” he explains, “promotes production as the highest value of self worth. How can you give old age a special, positive value which others do not possess?”

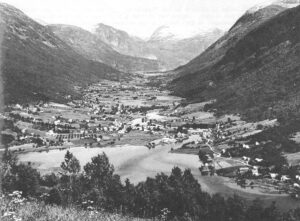

Production is the national goal as well. Currently, 70 per cent of the country is urbanized. By the year 2000, the figure will be 90 per cent.

In other parts of Europe, rural life is still the vanguard of individualism. In Sweden, the farmer is quickly losing out to the computer and national planner.

From the air, Ostersund, the forestry capital of Sweden, located in the center of the country, looks like a giant pincushion. White topped “needles” of snow-covered spruce and pine reach up towards the sky. But along the fringes are rickrack rows of attached condominiums.

Why the huddle in wide-open spaces?

“There is no choice,” says Milton Nilsson, principal of the forestry school. “Individualism is sacrificed to economics.”

Mechanization of the forests has cut the labor force from 360,000 in 1950 to 90,000 in 1970.

Mass unemployment plus lack of farm subsidies has caused large-scale emigration to industries in the South of Sweden.

Since it’s cheaper to buy agricultural products from Scandinavian neighbors, the government prefers to scrap farms and build industries. “Villages don’t fit the contemporary mold,” says Nilsson.

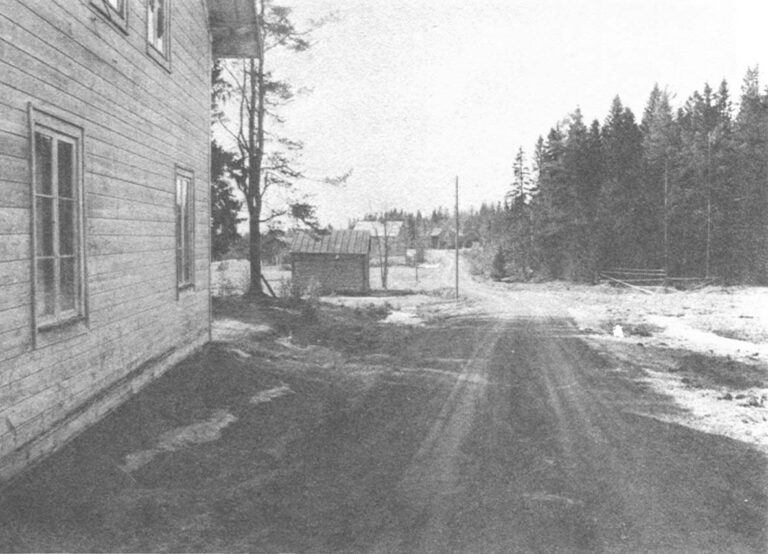

Some like Hallen become mini ghost towns.

Hallen

Once the six wooden houses, stained burgundy with iron oxide (typical of the countryside), were alive with 50 inhabitants. Today they represent an empty stage set.

“Here we throw away our aged in another way,” says Erik Hansson, a spinning-wheel maker living in nearby Ottsjön. “They are made to feel life’s labor is wasted as farms deteriorate and they are either left behind or forced to abandon their homes.”

Hansson lives with his wife, an artist, and his mother, 93, in a modernized farmhouse inherited from his father. Over a snack of homemade, fluted ginger cakes and coffee, he enumerates the number of lone aged who occupy surrounding farms.

Their children departed for independent factory lives in another corner of the country. If they return home to visit, says Hansson, it is only for the elk hunting in the fall and the chance to show off the wife’s new clothes.

He laments the dissolution of family ties and the disappearance of grandparents. Other than the perfunctory Christmas letter, grandchildren don’t know of their existence.

To fight the trend, he has joined “Pro-Föllinge,” a pressure group of high school teachers in the town of Föllinge. They are bucking the heavy industrialization proposed by Stockholm, which they dismiss, as a “narcotic of noise and smoke.”

“We want small industries that won’t destroy our nature and water,” says Lars Eliasson, a young math teacher and leader of the dissenters.

To employ farmwomen, skilled in weaving, Pro-Föllinge has already helped establish a small handicraft cooperative of a dozen looms.

Eliasson is also demanding funds to employ farmwomen as home aides to care for the elderly in their home surroundings.

“Now they are pulled off their farms and put into these nursing homes,” he says, as he leads a tour through one of them.

The Nolson Iolssons, an octogenarian couple, were transplanted 30 miles from home. They are in separate cubicles furnished with cheap, motel-like furniture.

Again the plight of loneliness. “There is no one to talk to,” admits a patient, “but they are kind.” “They should be more than kind,” mutters Eliasson.

“To the community” he adds, the aged are uninteresting. It took us three years to get benches for them near the post office, church and bank so they could pause to rest.”

Happiest, at any age, in any society, is the individual so absorbed in his work that little else matters.

In Kalmar, the glass-making district south of Stockholm, Bengt Heinze has been enchanted with the color and form of crystal for 56 years. Now the master blower at Kosta, the 220-year-old queen of the Swedish glass industry, he enjoys telling of his escapades at age nine when he broke a hole in the wall in order to blow glass as had his ancestors. Management finally gave in and at 16 he joined the ranks.

From the classical highball glasses to the intricate, multihued, pop art sculptures, Heinze does it all with a passion. To hear him talk, there’s unequalled satisfaction in taking a glob of molten glass and with a few puffs, turns and snips creating a swan.

“I feel like a musician with a pipe,” he says in an ebullient voice. “I love to feel beauty coming out of my hands.”

With his forceful, muscular physique he looks 45, claims to be 65 and says he feels like 28. He talks animatedly of three married daughters, four grandchildren, and a forthcoming holiday to the Canary Islands. One great wish is to visit the Steuben glassworks in the U.S.

His face is a perpetual smile, whether he chooses to joke about not having six schnapps glasses of the same size, or of a dream that the glassblower orchestra (of which he is also a member) played at his funeral.

“I never walked to the factory in discontentment,” he adds. “I hope to die with my boots on.”

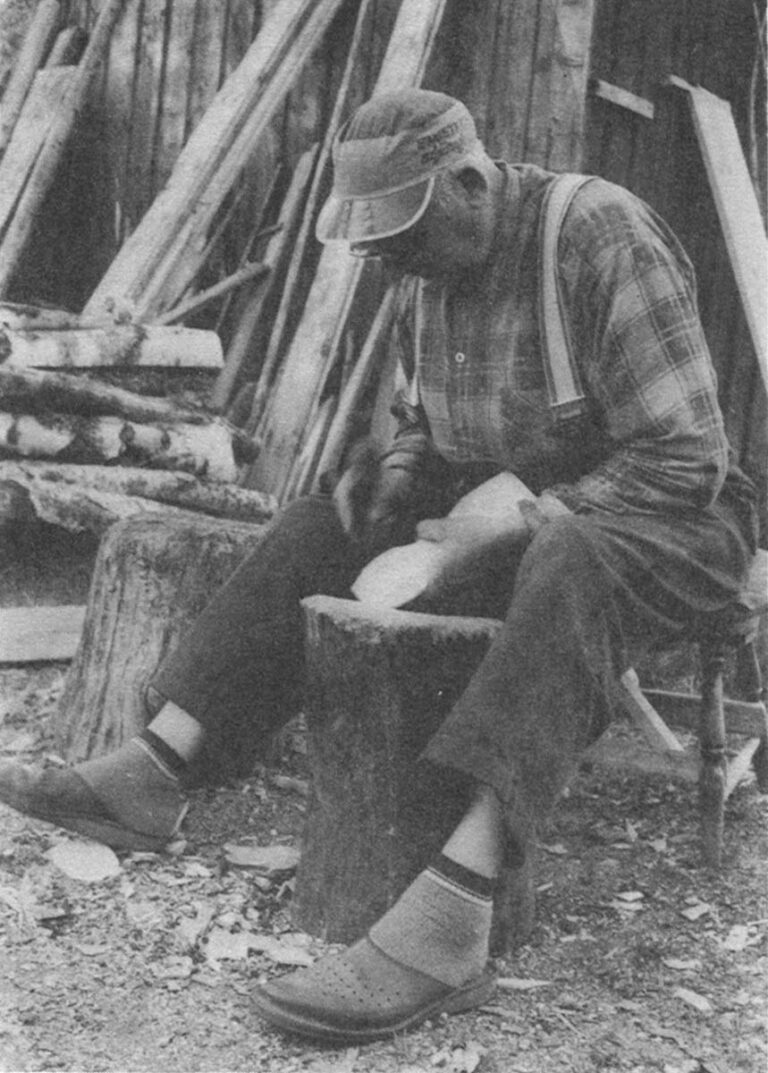

In the same region of Kalmar, Johan Karlsson, 69, lives deep in the forest area of Hästmahult near Gullabo.

Appropriate to the sound of the place, tracking him down is like living a page out of Hansel and Gretel. There’s no marked road. One has only a tic-tac-toe sketch drawn by a neighbor. (Near the last cross is the “gingerbread house.”)

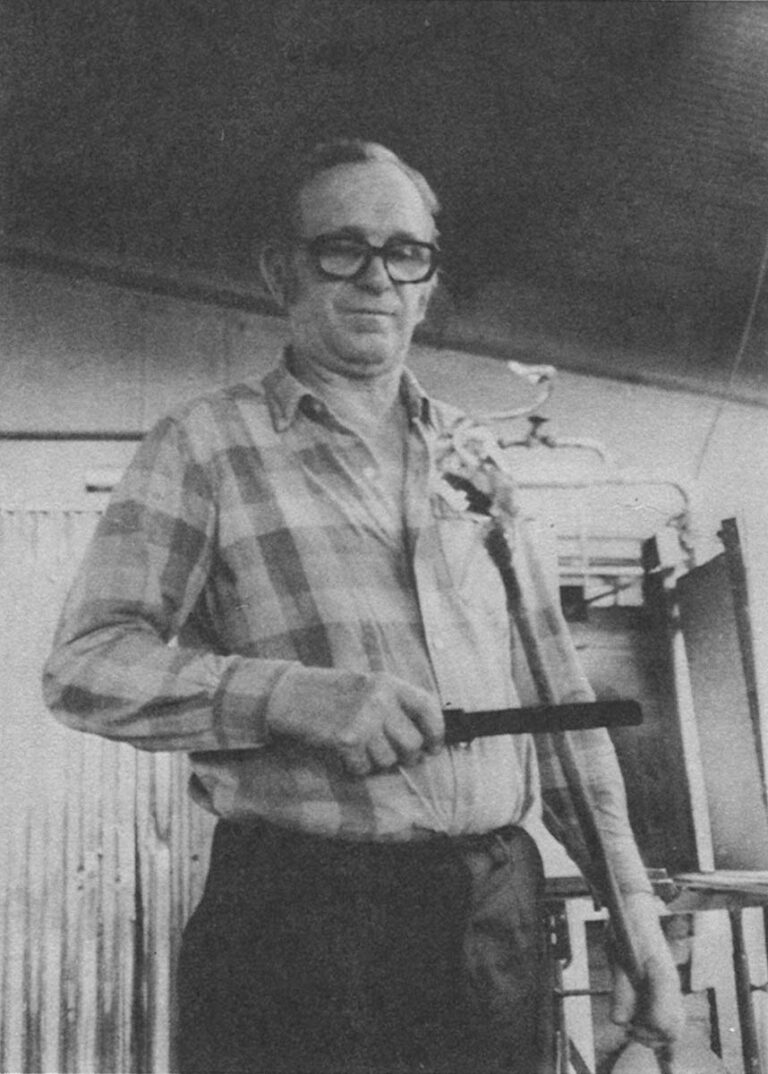

Karlsson is a large hulk of a man. A Paul Bunyan type complete with plaid shirt, suspenders and wooden clogs.

He, too, laughs often and heartily and hands are constantly busy working with wood. It’s one way of camouflaging shyness. Visitors are rare.

Karlsson selects a piece of juniper, a bit larger in size than fireplace kindling, perches on a stump near his tiny workshop, and begins to hack out a long-handled mixing spoon.

With a few strokes of a hatchet, then precise whittling tools handed his in nurse-fashion by his wife, he finishes the piece in 10 minutes. Then he adds it to the doll-like parade of others standing on the kitchen stove to dry.

He produces about 1000 such spoons a year for sale to tourist handicraft shops. Wife Anna helps by peeling birch branches for the broom-like gravy whisks.

Karlsson praises retirement and what he calls the relaxed life of woodcarving. As a forester, he had to get up each morning at three.

Now he has a pension, the supplement from carvings and a 2400-dollar government loan for renovating the bathroom and other plumbing. (All retirees in Sweden have the opportunity to borrow this amount, interest-free, with lifetime repayment.)

The Karlssons are also excited about their first vacation now that two cows no longer tie them down. Mrs. Karlsson proudly shows a photo of her uncle, 88, who has invited them to his island of Gotland near Stockholm.

For her, life has been isolated and lonely. The thought never occurred to him. “I guess I always have something to do,” he says.

One returns to Stockholm and again experiences the eerie feeling of “1984” coming true. George Orwell’s book, “1984” hinted at a programmed, robot-like society.

Reinforcing the sensation are best sellers like “Sweden 1985” with the book jacket illustration of a gloved hand holding a computer identification card.

Individuals debate the welfare society which “acerbates the problems by over satisfying physical needs and creates spiritual ones because the individual has more time to think.”

Statistics show a proliferation of automobiles, pleasure boats, summerhouses and campers. Also signs of stress: A whopping national health bill and a doubling of job absenteeism in the last two years.

Stockholm is growing and bureaucracy with it. Lars Persson, an editor of the daily Expressen, says, “Back in the social revolution of the thirties, we could handle it. There was the folk pension and cheap housing and we lacked immigration into the cities.

“As the city swelled and we built apartment complexes,” he continues. “The main thrust was a place to live and we threw away consideration of how a man lived. Authorities were closer to the people before. Now there is a new class of bureaucrats.”

Bishop Strom suggests architects need to face the problem of people living close again. The church itself plays a small role, if any, in bringing society together. The only effort toward the elderly, except for some home visiting by younger parishioners, is an annual boat excursion.

Some see a need for activity clubs and pubs for coming together. “Other countries practice it better than we do,” says Ulvenstam. “At the bottom,” he adds, “we need a more generous and human attitude from society and the individual.”

He is gloomy about the outlook. “Swedes have given up the idea of change,” he says. “We don’t even talk any more about neglecting our aged parents. In comparison, the Danes discuss their bad conscience on this problem more openly. But they were civilized when we were in caves and they have more of a town culture.

“One hundred years ago,” he adds, “most Swedes lived on farms. We have no deep roots of being with each other.

“It is a paradox of our society,” he concludes. “We are three times richer now. And three times more unhappy.”

Received in New York August 2, 1971

©1971 Nada Skerly

Nada Skerly is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. This article may be published with credit to Miss Skerly, The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star and the Alicia Patterson Fund.