Bristol Bay, Alaska–The shallow reach of the Bering Sea crashes between the shoulder and the arm of Alaska’s Aleutian mountain range. The tundra, receding in waves from the ocean, is flecked with small ponds two feet deep. White in winter, pale green in summer. the plains roll on almost a hundred miles with only an occasional stand of black spruce piercing the horizon.

Twenty trumpeter swans, almost extinct in the lower 48, turn their eyes skyward, then return to feeding. A brown bear and her two cubs meander undisturbed along the paths connecting one tundra pond to another. A small herd of caribou dig through sweet smelling grasses, happy to be done with lichen. Come November, hundreds of their kin will join them to migrate to their winter grounds.

For ten months a year, the sun skirts the landscape casting few shadows from human forms. Few people live on the western edge of the western world in winter and those that do wait within themselves for spring.

When the snow disappears for the last time in May, the first of the sockeye salmon, known as reds in Alaska, begin their journey home. Still hundreds of miles offshore, they turn and swim toward their natal rivers and streams. Each year between 20 million and 66 million fish arrive in Bristol Bay during a three week period. It is a biological miracle.

Just as the red salmon return, so too the men and women of the Bristol Bay fishery. The doctors, the lawyers, the drug runners, the teachers, the writers and chemists, biologists and psychologists, the stock brokers and opera singers, all leave their outside jobs and join the locals to chase the gold that rides on the backs of the reds.

Mammas don’t let your babies grow up to be fishermen

Don’t let em pick guitars and buy fishin’ boats

Let em be doctors and those kinds of folks

Mammas don’t let your babies grow up to be fishermen

They’re never at home and they’re always alone

Even with someone they love.

Pete Blackwell,

with regrets to Ed and Patsy Bruce

Late June, 1986

The cowboys of the sea are nervous. The largest salmon run in the world is late. Twenty-four million reds should be converging on Bristol Bay now. There’s big bucks to be made in the Bay; big bucks to lose in this crap shoot of a fishery. The ante, however, is high.

Only 1,800 drift gillnet licenses, or permits, are granted for the limited entry fishery of Bristol Bay. The sale price on these permits topped $124,000 in 1986.

The investment doesn’t stop with the permit. Every group of three or four boats represents a quarter of a million dollars. The nets piled high on deck cost thousands, insurance for the nation’s most dangerous occupation is outrageous and an airplane ticket home starts at $800. A skipper needs to make at least $36,000 to break even.

June 27

The Dillingham boat harbor is quiet. The odd jobs are done. The small talk long since talked. All are waiting, wondering and worrying about the 24 million missing reds. Are they late? Are they coming? Whispers have it that the Japanese, or El Nino, got ’em. If true, it means another season of uncertainty, another winter of want–most of the gillnetters count the profits from the six week fishery as their only income.

Men and women hang out in Tent City, a collection of 24 tents and tarps. The fishermen from as far away as Costa Rica and Austria hope to be hired as crew for one of the 250 drift gillnet boats moored below in the harbor.

Beans have replaced burgers in the camp and a community pot bubbles on the fire. Bugle tobacco and Top papers have long since replaced the preferred factory-rolled Camel straights. Some folks have been around so long that they’re having trouble paying the two buck a night charge.

“Hey man, you get a job?” one man asks of the figure approaching the fire from the direction of the docks. A smoke is proffered at the negative answer.

The conversation turns to the previous day’s opening at Egegik, one of the Bristol Bay districts. Only 200,000 fish were caught by 555 boats. The average catch of 1,200 pounds per boat indicates that the peak of the run is still several days away. Discouraged moans greet this news.

In the words of one seafood processor manager, “It’s getting to be nail-biting time.”

June 30

At 9 a.m., the Alaska Department of Fish and Game announces an opening. “Fishing shall be permitted for drift nets in the Nushagak District for a twelve hour period starting at 1800 hours. Good luck and good fishing.”

For the first time in three weeks, the sky is clear.

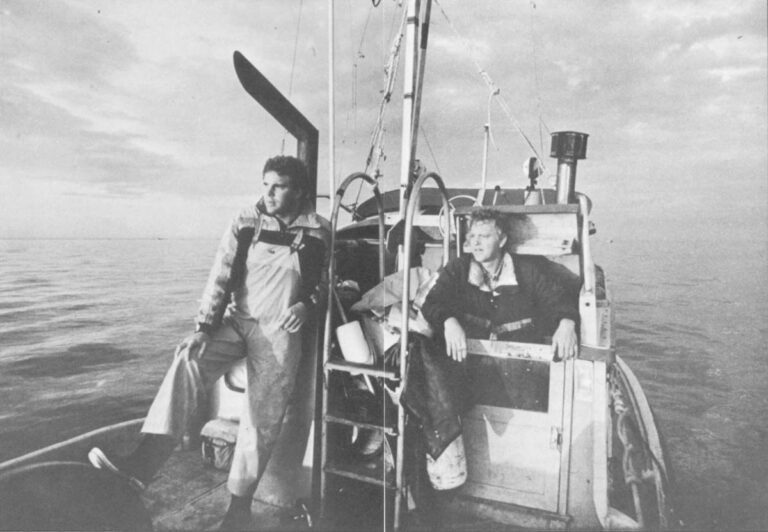

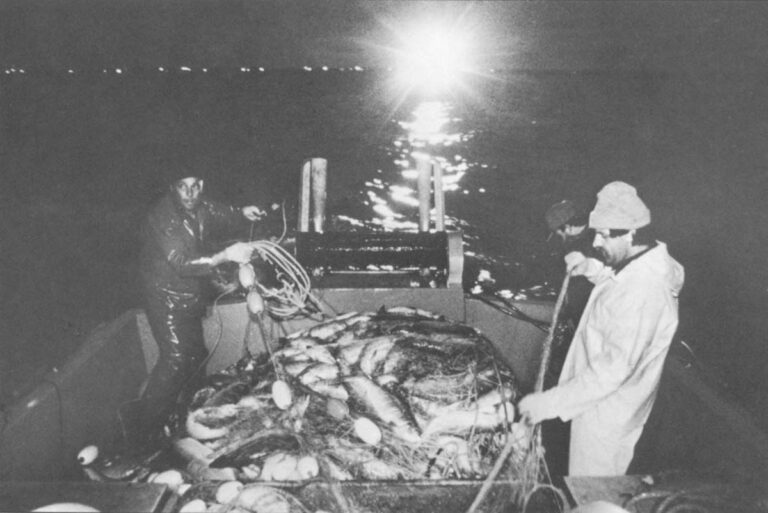

Dale Gorman and his deck hands, daughter Mary and Kelly Kerrone, watch the net fly from the reel as the Molly Ann surges forward. All strain to see if the fish are hitting the mesh.

Often an entangled salmon bolts, creating a smoke-like mist as he charges to the surface. Fishermen dream of dancing fish and smoking nets.

The first set is disappointing, 20 fish. The second depressing, as 10 are picked from the nylon. Dale had gambled, setting his net where he knew salmon had been the night before. Now he was stuck: he couldn’t make headway with the nine knot tidal current ripping against the boat. He would have to wait until slack water to make his move.

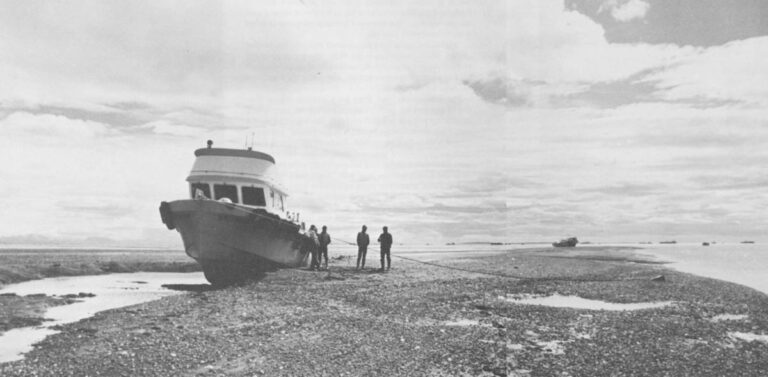

Gorman is certainly not the first person to lose to the eccentricities of Bristol Bay. The bleached bones of deserted canneries bear witness to that.

The demand for canned salmon has decreased during the last few years. Most of the product is fresh frozen and shipped to Japan. Almost 80% of the processors and canneries in Alaska and British Columbia are owned in some part by Japanese concerns, according to industry observers. The freighters with Kanji script on their sterns remind the fishermen that the yen, not the dollar, powers the market for their fish.

All night Mary and Kelly extricate the salmon from the gillnet and return it to the water. The sea’s chop has given way to a mirrored surface reflecting the glow of the setting sun to the northwest–even as the glow of the rising sun is appearing 60 degrees to the northeast. It is one of those rare sunrises in Bristol Bay where the sun can be seen.

Dale powers toward the tender boats to unload his fish and pick up supplies. He is exhausted from working all night. His catch for the twelve hours was less than 4,000 pounds. He was hoping for 10,000. A rainbow is discernible on the horizon. “That’s where all the fish are,” he says.

“Yeah,” says Kelly, “the pot of gold.”

Many fishermen believe that pot is in Alaska. Five of six species of salmon are produced in the state’s 2,000 to 2,500 streams and rivers. Widespread development has yet to eat the landscape or irrevocably damage the salmon streams as it has “outside” in the lower 48 states. The greatest threat to the resource has always been over-fishing.

Since 1741, when Aleksei Chirikov discovered Prince of Wales Island, Alaska’s natural resources have been assaulted. The Russian settlement of New Archangel, now known as Sitka, became the center of the fur trade. Aleut hunting parties ranged hundreds of miles from the outpost searching for the fur animals their Russian employers craved. Populations of seal, sea otter, beaver and walrus were decimated and all but disappeared.

Salmon was initially spared because it couldn’t be preserved adequately: the salted fish often spoiled during the lengthy voyage to European markets. When William Hume and Andrew Hapgood of Sacramento, California, improved upon Frenchman Nicholas Appert’s canning technique in 1864, the North was invaded by canning companies. Thirty-seven canneries were in production in 1888, only ten years after the establishment of the first cannery. Eventually, 156 would be operating from Ketchikan to the Yukon River.

Companies throughout Alaska illegally blocked streams in an attempt to increase their catch of salmon. The four fishery enforcement agents who patrolled most of the territory’s 33,904 miles of coastline before 1913 could not hope to stop the slaughter. Greed destroyed great runs.

In 1919 two federal fisheries agents expressed astonishment that any salmon were left in Alaskan waters. C.H. Gilbert and Henry O’Malley reported, “The industry has now reached a critical period, in which the salmon supply of Alaska is threatened with virtual extinction…”

Throughout the next forty years the numbers of returning salmon seesawed, peaking one year, plummeting the next. The resource went “right to its knees,” according to Mike Nelson, an Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologist with 25 years experience in the Bristol Bay region.

Part of the problem was the Federal management of the territory’s fisheries. The bureaucrats in Washington, DC set the number of weekly fishing days before the season began. Any change in this schedule had to be printed in the Federal Register before being implemented. This process took two weeks during which an endangered run could be destroyed by continued harvesting.

Stewardship of the resource was assumed by the new state after it was formed in 1959. Statehood “put resource control under local management on a day to day basis,” said Nelson, making in-season management more efficient and timely. If a salmon return was weak. the area’s biologist could shut down fishing immediately. Most streams’ salmon populations stabilized.

Alaska legislators initiated a system of limited entry for the fisheries during the early seventies. The limited entry program keeps the number of fishermen constant by issuing a set number of permits for any given area. This, coupled with increased monitoring of the fleet and better knowledge of the salmon’s biology, has made over-fishing essentially a problem of the past.

During the early heyday of canning, local labor was augmented by men hired from Seattle and San Francisco. Swedes, Norwegians, Finns, Czechs and Italians worked on the sailboats. Chinese, Indians, Aleuts and Eskimos worked onshore. The companies, particularly in Bristol Bay, supplied everything for the fishermen and workers: food, shelter, clothing, boats and gear.

“Monkey” boats towed long lines of open sailboats to the fishing grounds, as it wasn’t until 1952 that power fishing boats were allowed on the Bay. Once there, the two-man crew toiled until the hold was full of fish or their supplies depleted. It was a tough life with few amenities and many dangers. But the goal was simple: to catch as many reds as possible.

Today, the double-enders have long since been replaced with fisherman-owned aluminum and fiberglass hulls complete with shower and head. Hydraulically powered reels, not the muscles of arms and backs, haul in the nylon, not linen, nets. Instead of one woman for every thousand men, there’s one for every hundred. But the goal remains the same–to catch so many fish you have to wiggle out of the stern.

July 4

The Fourth is an important day at Dago Creek. It is the traditional peak of the Bristol Bay run. While most “outside” enjoy the day off from work, the boys on the beach would rather be fishing. Due to a midseason closure, four hundred boats, 1,200 fishermen, sit high and dry on the sand.

Four men living in a six foot by eight foot cabin make privacy an unknown luxury. The best attribute one can have is the ability to be very inconspicuous: plain in personality, small in possessions. It doesn’t hurt to have a sense of humor when the sight of a severed salmon eye perched on the sink breaks through the residual fuzz from a sleepless night of working.

“The interesting part of this job is finding out how far you can push yourself and still function in an efficient and safe manner,” says Bob Griswold, a fisherman on the Tanglewood 6, a vessel nicknamed the “geriatric boat” by its skipper because no one is on the “sunny side of forty.”

“The fishermen are people who test their limits in their personal life as well and this is just another manifestation of their philosophy on life,” says Griswold, a world class acrobatic snow skier.

“Fishing gets in your blood,” says Dale Gorman. “It’s more than an occupation. It’s a way of life with higher highs, lower lows and friendships forged by living on the edge.”

July 8

The thirteen hour opener is scheduled to start at 11 p.m.. Almost 700 boats are registered to fish the Ugashik district: twice as many vessels and two-thirds less harvestable salmon than in 1985. The only good news of this season is that the price being paid by fish buyers is up to $1.60 per pound from last year’s 90 cents a pound. One hefty load of fish represents a boat payment. One error in judgment may result in bankruptcy.

The thirteen hour opener is scheduled to start at 11 p.m.. Almost 700 boats are registered to fish the Ugashik district: twice as many vessels and two-thirds less harvestable salmon than in 1985. The only good news of this season is that the price being paid by fish buyers is up to $1.60 per pound from last year’s 90 cents a pound. One hefty load of fish represents a boat payment. One error in judgment may result in bankruptcy.

Brad Larsen studies his charts trying to second guess the salmon. The skipper of the Sapphire believes the fish have been schooling, waiting for the right combination of rain, wind and tide to occur before they move upriver. Brad thinks he knows where the reds may be hiding.

No one is talking. Jim Schmidt makes peanut butter cookies and gazes out the windows. Pete Blackwell repairs a net and Phil Russo reads.

At 10:55 the nets of the surrounding boats are in the water. Brad, nicknamed Honest Abe by the crew, holds off. Precisely at 11 p.m. he gives the signal and the nets are dropped.

Silence on deck. “Born in the USA” plays softly in the background. All four men jump as tail-dancing salmon slam into the net. Spray explodes from the corks.

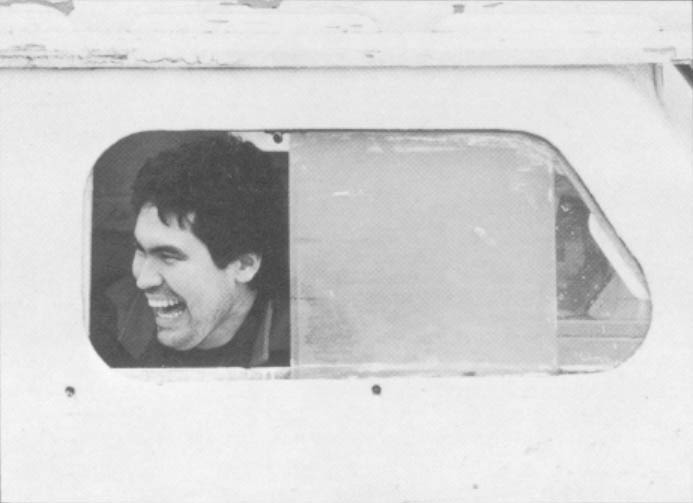

“We got a hit, there’s another, another, God we’re smoking!” says Pete. “Skipper, you put us on to em!”

Not believing his eyes, Brad shoves his hands deeper into his pockets, worriedly looking at the other nets laid 20 yards away. He watches the mist appear from his net like smoke. His disbelieving smile turns into a grin that finally splits into a full-bellied laugh as he realizes that what he has dreamed about during the winter has come true. The net is in danger of sinking with the weight of so many fish. His crew will literally have to wiggle out of the stern as 1,000 fish, 6,000 pounds, $9,000 lay on deck.

The Bay’s returns for the last few years have been record breaking: 1980, 62.5 million fish. and 1983, 45.8 million fish. Last summer for the first time in six years the return, 23.9 million, was down to the twenty year average. With the total harvest half what it had been in 1985 and the fish late, state biologist Mike Nelson was under pressure. “A lot of seasons were riding on one decision,” he said.

Managing salmon is difficult at best. The goal seems simple at first glance: enough salmon must survive years at sea as well as “escape” the commercial and sport fishermen. The number of salmon allowed to continue to the rivers to spawn is controlled by fishing season closures.

Each river system consists of salmon-producing tributaries. These tributaries produce many runs of genetically unique fish. All have different qualities and characteristics. All runs need to be protected.

For example, the Kvichak River in the Naknek-Kvichak fishing district has two different age group runs of red salmon that return at the same time. Last summer the escapement of the five-year-olds proceeded as predicted. The four-year-olds, comprising 75% of the river’s population, did not show up. Concerned biologists closed the river as well as the district to fishing.

The Naknek, another river in the system, also had a red run returning. Its escapement goal had been reached. In fact, too many adults had already returned and were tearing apart the previous spawners’ redds, or nests, thus damaging a future generation of the earlier arriving run.

In the meantime, the commercial fishermen, who had thousands of dollars riding on the success of the fishing season, were screaming for the opportunity to fish. The sport fishermen, many of whom had journeyed to the area at great expense, were screaming to fish.

Add to this the vagaries of nature as well as the need to balance a multitude of international treaties and allocation agreements and one begins to get an idea of the complexities of managing this resource.

July 11

Dale Gorman is down. The Molly Ann’s total catch up to this point is 29,000 pounds, the equivalent of three days work in 1985. And missing one fifteen thousand pound average opener because of a fishing regulations technicality was disastrous. “That cost me $20,000,” he says. He’ll have to find a winter job for the first time in years.

Dale lounges on the stern after an all night opener. “Now it’s time for a little R and R, rest and Rainier,” he says as he opens a can of the northwest-brewed beer.

He’s thinking about his son. Larry, a mechanical engineer, is saving money to buy a Bristol Bay permit. “I don’t know whether to encourage him or discourage him,” says Dale. “In the short run it would be fine, in the long run, no. Soon as they build a road, I’ll give it thirty years before the run goes the way of the rest of them.

“You know, if a guy sold his boat and permit, he’d get a quarter of a million dollars. If he invested that and got 10% return, he’d make $25,000 a year,” says Dale. “You fish because you love it. It makes no business sense whatsoever but it’s the funnest way to make money I know of.” His lined face cracks a smile.

September

Bristol Bay is quiet. Full-racked caribou shy as the wind kicks up last summer’s trash from a fisherman’s dinner. Brown bears, fattened on the flesh of salmon, trek to their winter dens. Trumpeter swans glide on the lakes with exclamation points of goslings following.

The tundra has dulled to its fall drab. The hills have been brushed with the first snow, termination dust, the locals call it. It’s the end of the summer, the end of the $144 million fishing season, the beginning of winter. The salmon are spawned out. The cowboys are gone.

Salmon Fishing Techniques

The main techniques used by fishermen are as follows:

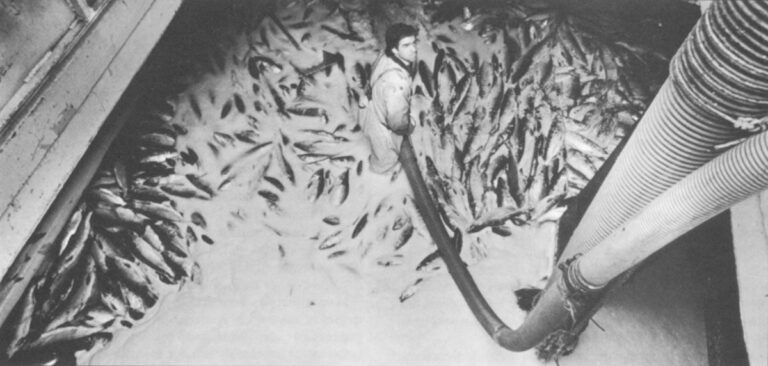

Drift gillnetting: This is used primarily in bays and estuaries from Bristol Bay to Oregon. The shallow boats are 15 to 35 feet long and operated by one to four people. A 150 fathom, or 900 foot, net is laid out for anywhere from a few minutes to many hours. The gillnets work simply: the salmon swim into the nylon mesh which entangles their gills. The net is pulled back to the boat where deck hands extricate the salmon. A set can produce a few fish such as those in Puget Sound or over a thousand in Bristol Bay.

Setnetting: Similar to drift gillnetting, setnetting is done from Alaska to California. One end of the gillnet is affixed to shore while the other is supported by a float or buoy. When the tide comes in, the water covers the net allowing salmon to swim into it. The net is picked when the tide recedes.

Trolling: This hook and line fishing is done from Southeast Alaska to California. The boats range in length from 15 to 45 feet and are designed to ride ocean swells like jockeys on thoroughbreds. One or two people work the two to four poles which support two lines each, 12 hooks per line. The quality of fish caught in this manner is exceptional. The salmon are dressed and individually iced within minutes of being brought on board. An average 17 hour day’s catch ranges from a few fish to a couple hundred.

Purse seining: This is used from Southeast Alaska to Washington. The boats are large–40 to 70 feet long and are operated by four to seven people. While a powerful skiff holds the end steady, the mother boat pulls the 334 fathom, 2000 foot, net around the fish. When the two boats meet, the net is drawn up like a purse, capturing all the salmon within the circle. The purse is pulled from the water, the fish placed in the hold. One net can contain thousands of fish. It’s easy to see who has had a successful season. One broom affixed to the mast means the boat’s crew “swept ’em clean” and harvested over 100,000 fish. Two brooms in the mast and they’ve hit 200,000 and are probably celebrating in the bar.

Fish traps: The Tsimshian Indians of Metlacatla, Alaska, operate the only fish trap in North America. All other traps and weirs were outlawed in the 1930’s. The trap is located close to a salmon stream. Fish swim through a one-way passage into a holding pen and are harvested when the pen is full.

©1987 Natalie Fobes

Natalie Fobes, photographer on leave from the Seattle Times, is chronicling the Pacific Salmon and their struggle to survive.