The cool evening breezes have not yet evaporated the remainder of the sweat between the spectators’ shoulder blades. Shielding their eyes from the sun, they stare transfixed at the rushing water before them.

“Yea! Looky there.” Twenty-one heads swivel in time to catch a shadow playing across the water.

“All right!” Forty-two eyes glimpse a flicker of fin.

Beer bottles and popcorn are passed from hand to hand, from Chevy to Ford pickup. VW to Bonneville. This is the best show playing in Toppenish, Wash., this night in May. There’s a collective gasp as nineteen pounds of streamlined muscle bursts from the foam, suspended in the spotlight of the setting sun. The spring chinook, the king salmon have returned to the Yakima River. Once more the fish have survived the precarious journey home only to procreate and die.

While the great mystique of the salmon is appreciated by those watching, most don’t realize that the fish represent between .06 and 2.5 percent of the millions of eggs laid four and five years ago in this same river. The survivors faced man-made obstacles during their journey to and from the sea: dams, irrigation ditches and pollution. The salmon evaded such natural predators as fish, eagles, bears, seals and orca whales. They escaped the nets and lines of the most efficient predator of all, the fisherman. And now they’ve returned to start the cycle anew.

The six species of Pacific salmon are native in streams from San Francisco Bay to Alaska, from Siberia to Japan and Korea. Five species–chinook, coho, chum, sockeye and pinks–are found in North America and Asia. The sixth, masu or cherry, lives only in parts of Asia.

Each species of Pacific salmon has its own life cycle patterns. Each watershed produces many runs, or groups, and each run has many genetically unique races. The races have evolved over time to utilize the season during which they return and the particular characteristics of the parent stream. A fish may migrate up to 10,000 miles in the ocean only to spawn within yards of its freshwater birthplace.

The story of Pacific salmon is analogous to that of other natural resources once thought so abundant that no harvest practice could affect them. During the past 120 years, man has over-fished the resource and destroyed its habitat from California to Alaska to Japan. Many stocks disappeared altogether, others numbers declined drastically. Washington’s Columbia River runs for all species has been estimated as 16 million in 1850. Today adult returns may be 2.5 million. Because the fish need cool, clean, rapid running water to survive, they are indicators of the soundness of the environment. Improper logging and mining techniques can clog the streams with sediment and debris; irrigation needs may drain the rivers; pollution from fertilizers, pulp mills and inadequate sewage treatment facilities might poison the fish.

Difficult decisions will be made in the next few years concerning the fate of Pacific salmon. Managers of this resource must decide how to balance the complex array of demands from resource users with the biological needs of the fish. The dilemma may well be a choice between preserving jobs or preserving a natural resource.

And while government and tribal agencies will determine who will fish and how many can be harvested, it is the public that decides at what price this resource is preserved for future generations.

Route 14 winds beside the water on the Washington side of the Columbia River Gorge where the basalt cliffs rise straight up. The area is home to Ponderosa Pine and balls of sagebrush. Trucks rumble along the two lane, potholed and patched road passing the first sailboarders of the season. The men and women who ride the wind and the river have declared the partnership of the still, dammed waters of the Columbia and the 40-mph winds of the Gorge the second-best surfing conditions in the world.

About the time the Toyota vans loaded with sailboards begin arriving in White Salmon, the spring chinook make their way up the rivers. In the old days, the Indians say, the appearance of swallows and seagulls heralded the return of the life-giving salmon. Now it is the sailboarders and the biologists. For many Yakima Indians the time has come to load their long poled nets atop cars and pickups and return to the Klickitat River, one of the last relatively unspoiled tributaries of the Columbia, to fish in the ways of their ancestors.

Dave Leonard, Jr., guides his 34-foot dipnet through the rushing rapids twenty feet below. He is suspended over the emerald-hued water on a scaffold made of two-by-fours and plywood and hung from the sheer face of rock by rusted cables. Gently he caresses the stream bottom with the four-foot net attached to the pole, pulling hand under hand, pushing hand over hand, moving slowly from one end of the five-foot platform to the other, seeking out the hidey holes where the fish rest to gather strength before assaulting the falls twenty yards upstream. His face is a study of concentration and sweat. Years of fishing this same spot has taught him where the rocks under the surface are located. He is careful not to hit them because the sound would send the fish into hiding.

His father, Dave Leonard Sr. and a friend, Wilbur Slokish, rest behind him on the sun-heated rocks. Dip netting is tiring. The weight of the pole and the awkward maneuvering takes its toll on the muscles of the back, arms, stomach and legs. A strong man can’t fish for more than an hour without needing a break. The three take turns.

Dave feels the pole quiver. He pulls rapidly putting his weight into the action. His father and Wilbur stop their conversation. The net is in view. It’s a salmon and a good sized one at that. Dave thunks it once on the head and disengages it from the net. A small smile and he hands the 18-pound fish to his father to place under a wet burlap bag. The men have been successful today: seven fish.

No one knows how long the Indians have been fishing in the valley using this age-old technique. “Salmon was a zon. Each year the inhabitants of this underwater mansion would don their fish costumes and return to the river to sacrifice themselves for the Indians. Normally a chief or scout would be sent to learn if the Indians were following the required rituals. This fish would be the first salmon caught.

The catching of the first salmon was a time of celebration, thanksgiving, respect and joy. Once again the cycle of life was beginning. The fish was treated with honor. Songs, prayers and sometimes dances were performed before the fish was butchered with a flint or shell knife. All the people of the village would share the flesh. With great ceremony the intact skeleton was placed in the water so its spirit could return home to guide his fellow salmon people to the stream.

Most tribes no longer perform the ceremony. Washington’s Tulalip and Yakima tribes, as well as some tribes in British Columbia and Alaska, still mark the arrival of the first salmon with celebrations and feasts. The Tulalip Salmon Ceremony takes place in June.

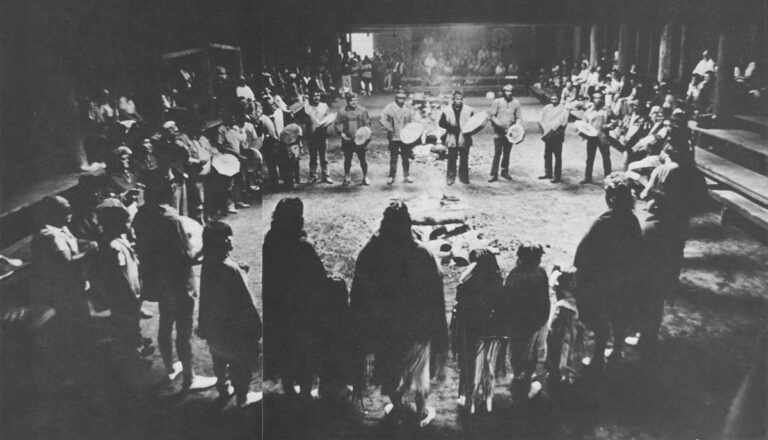

The rain sputters through the large ventilation holes cut in the roof of the cedar-sided long-house on the Tulalip reservation near Marysville, WA. As the moisture hits the three sparking fires made of cedar logs, it creates eye-watering smoke. One hundred and fifty people, Indian and non-Indian alike, have come this blustery day to welcome “haik ciaub Yo bouch,” big chief King salmon, back home.

The ceremony was recreated eleven years ago from recollections of the elders. “With 20th-century technology exploding at such a rapid rate…we, as a people, find we must go back to remember our roots and traditions,” said Wayne Williams to the assembly.

The rites begin as the drummers and singers move across the dirt floor. At each corner, north, south, east and west, the song of welcome crescendos, becoming a cacophony of rich, soul-stirring sound. The light plays gently upon their figures as they sing, dance and tell legends of the salmon, passed from generation to generation.

People move from the building to the bluff overlooking Puget Sound, anticipating the arrival of “Yo bouch.”

The salmon, swathed in fir boughs and placed on a litter, is carried back to the long-house for more welcoming songs and dances. The procession weaves its way through the parking lot to the community center. The gym has been converted into a cafeteria.

Plates of alder-roasted salmon are consumed. Because the fishing season is not yet in full swing, fish have been bought from a coastal tribe and roasted since 6 a.m. After everyone has had his fill, it is time to return the bones of the ceremonial fish to the water.

The 50-year-old dugout is maneuvered far off shore. The chanting words, “Hoy yough ciaub, Oh tok wa ciaub,” (farewell big chief, return safely home) drift across the distance as the skeleton is gently placed in the water, head towards the west, continuing a long-standing tradition.

The Indians employed a number of sophisticated techniques in catching the fish, noted Hillary Stewart in her book, “Indian Fishing.” They used gill, dip, seine and set nets made of bull kelp, cedar bark, whale sinew or nettle fiber. They trolled in their dugout canoes holding the nettle fiber line in their paddling hand or looping it on a supple willow stick in the stern. They trapped the fish with weirs made of fir, maple, cedar or willow branches stretched across streams and set up tidal fence traps made of stone or logs. The salmon could cross these encumbrances easily during high tide but would be left high and dry when the water retreated. Spears, harpoons and gaff hooks were also used.

The Indians employed a number of sophisticated techniques in catching the fish, noted Hillary Stewart in her book, “Indian Fishing.” They used gill, dip, seine and set nets made of bull kelp, cedar bark, whale sinew or nettle fiber. They trolled in their dugout canoes holding the nettle fiber line in their paddling hand or looping it on a supple willow stick in the stern. They trapped the fish with weirs made of fir, maple, cedar or willow branches stretched across streams and set up tidal fence traps made of stone or logs. The salmon could cross these encumbrances easily during high tide but would be left high and dry when the water retreated. Spears, harpoons and gaff hooks were also used.

Because of the effective techniques and the relative short span of the run, “The determinant of how many fish was caught was likely the number of female hands available for processing,” said anthropologist Wayne Suttles, Professor Emeritus at Portland State University, “rather than the number of male hands there to catch the salmon.”

There was little evidence of hunger among the Indians who relied on salmon. “There were no famines with so much fish,” said Lonnie Selan, Cultural Resources Specialist for the Yakima Nation. “Everyone was taken care of.”

There is no evidence of over-fishing by the Indians during that time.

The Indians realized the flood of white settlers would not stop. Even though the Indians outnumbered the non-Indians and likely could have destroyed them, the tribes signed 11 treaties with Northwest Territories Governor Isaac Stevens between 1854 and 1855.

The treaties did not give rights to the Indians, contrary to popular belief. The Indians, through the treaties, gave certain rights to the non-Indian settlers. The tribes retained the right to fish exclusively on the reservations and, as stated in the treaties, “the right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations in common with all citizens of the Territory.”

These words would play a critical role in a federal district-court decision almost 120 years later that upheld the treaty tribes right to fish.

During the intervening years, the Indian fishing grounds were used increasingly by non-Indian sport and commercial fisheries. A lucrative canning industry developed in which some Indians were employed. Commercial nets stretched from bank to bank on some rivers allowing no escape for adult spawners. Traps and wheels worked with deadly efficiency until the late 1930s.

Watersheds were logged and mined. Rivers were dammed to meet the demand for hydro-electric power and dry-land irrigation. Housing developments blossomed. Fewer fish returned to the rivers. A resource once thought infinite was depleted. And as a result, the number of Indian fishermen plummeted.

Lawrence Webster, 87, recalls that by the late 1960s only one or two Suquamish tribal members were still fishing. The others had been forced out by state regulations and a lack of fish. It hit the old people the hardest, he said. “To them the salmon was like a religion.”

“Once the salmon are gone, the Indians say they’re next,” said Lynn Hatcher, Fisheries Director for, the Yakima Nation.

The Indians felt something had to be done.

The United States, acting as trustee for several Washington tribes, filed a complaint in 1970 initiating action against the State of Washington. The suit advocated reactivation of Indian treaty fishing rights. At that time Indians caught only 5 percent of the harvestable fish and owned less than one percent of the 6,000 commercial licenses issued by the state.

For more than three years federal judge George H. Boldt heard testimony from anthropologists, biologists, fishery managers and others concerning the importance of salmon to the Indians, the biology of the fish, and the commercial and sport fisheries in the area north from the Columbia River drainage and east of the Cascades.

Before issuing his findings he noted “More than a century of frequent and often violent controversy between Indians and non-Indians over treaty right fishing has resulted in deep distrust and animosity of both sides.”

Feb. 12, 1974, Boldt presented his decision. The judge found the twenty treaty tribes were entitled to half the harvestable return of salmon at all their historic fishing areas and places. He also stated the environment of the streams running through the reservations could not be impinged. These edicts were to receive top priority, second only to the conservation of the resource.

The citizens of Washington reeled from the implications. Confrontations between Treaty and non-Treaty fishermen were common, boats were sabotaged, people were injured during fish-in demonstrations. The state’s Department of Fisheries and Department of Game, as well as commercial and sport fishermen, sometimes refused to comply with the decision. Eight times treaty fishing rights were argued before the United States Supreme Court during the next few years. Eight times they were upheld.

Twelve years after the decision the number of Indian fishermen in the state has doubled while the number of non-Indian fishermen has decreased by a third. Treaty catches reached the 50 percent level in the 1984-85 season.

The rough water of the last few years appears to be smoothing out. A spirit of cooperation between the state agencies and the Tribes is surfacing, brought about in part by Washington Department of Fisheries (WDF) chief Bill Wilkerson. One month after becoming director in 1983 he organized a two day meeting between the state and the tribes. The participants aired their concerns and agreed a common goal was to manage the resource effectively. Before this meeting WDF and the tribes had gone to court 70 to 80 times a year to do battle over Indian fishing rights. The WDF and tribes have been in court only three times in the last three years for a total of 15 minutes. “And those were technicalities,” said Tony Floor, WDF spokesman.

“The best thing that happened to the resource was the Boldt decision,” said Larry Wasserman, a biologist with the Yakima Nation, because it forced the state to become accountable for the salmon harvest.

Many agree. “It was the first turning point in bringing responsible management back to Washington,” said Floor.

Although the fishing waters appear to be calm, one has only to look beneath the surface to find lingering animosity toward the Indians. This year’s sermon during the annual Blessing of the Fleet service at Seattle’s Fisherman’s Terminal stressed the importance of understanding, cooperation and acceptance of the Boldt decision. Not all of the thirty fishermen and fifty spectators wanted to listen.

One non-Indian gillnetter scratched his beard as he looked at the row of moored non-Indian fishing boats.

“The Indians destroyed a way of life,” he said. “They better not try to tie up here.”

Pacific Salmon

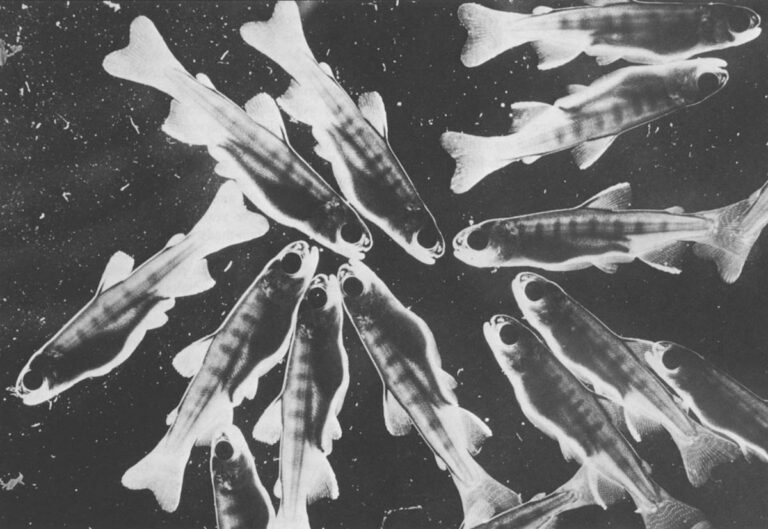

While each species has its own characteristics, all Pacific salmon follow the same basic life-cycle.

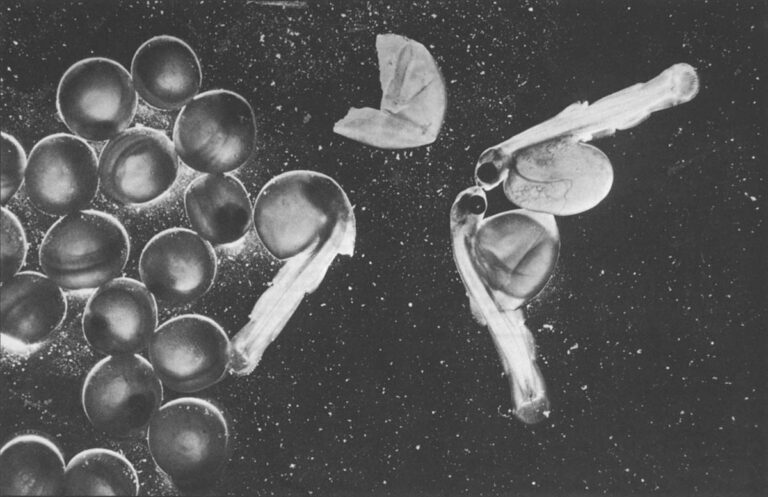

When the sexually mature adults reach the spawning grounds the female digs a redd, or nest, in the gravel with her tail. She deposits 1,500 to 5,000 eggs as her male suitor blankets them with milt or sperm. The eggs are covered by the gravel under which the young will stay until they emerge as fry three to five months later. All Pacific salmon die after spawning.

The embryo exists on food in its egg sack. Fifty to a hundred days later the embryo hatches, becoming an alevin. When the yolk is absorbed the small fish, called fry, emerge. Some species immediately migrate to the ocean, others build strength and bulk before making the journey. Eighty to ninety percent of the fry don’t survive the trip downstream. Those that make it to the river’s mouths linger for a few days during which their bodies adjust to the higher sodium content of the ocean water.

These powerful creatures may travel up to 4,000 miles per year in a primarily counter-clockwise orbit through the North Pacific. They stay at sea from one to five years. It is not uncommon for a fish to swim 18 to 30 miles per day without rest during its homeward migration. Once in the parent river, the salmon swim anywhere from a few yards to coastal streams to 2,000 miles in the Yukon River to return to their spawning grounds.

How do the fish find the parent stream left years before? A number of theories have evolved.

Ocean currents may lead the creatures to the coast. Researchers have discovered that salmon have sensory ganglia which respond to currents.

Some think salmon can detect variations in the earth’s magnetic field and use this information to chart a course to the coastline area of their stream.

Probably the most widely accepted idea is that once in the vicinity of its parent stream, the fish’s sense of smell can detect differences in the water. This trail was imprinted during the juveniles’ seaward migration, and the adult literally follows his nose back to the stream.

FUN FACTS

Chinook, tyee, king

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Freshwater life: a few months to over one year

Saltwater life: 1 to 4 years

Average weight: 20 lb.

Range of weight: 2 1/2 to 125 lb.

Chinook tend to be found in large rivers such as the Columbia, Fraser and Sacramento. The largest of all salmon, it is prized by both commercial and sports fishermen. It is not abundant in Asia.

Sockeye

Oncorhynchus nerka

Freshwater life: 1 to 3 years

Saltwater life: 1/2 to 4 years

Average weight: 6 to 8 lb.

Range of weight: 2 to 12 lb.

Sockeye must spend one year in a freshwater lake before migrating to the ocean. The red, oily flesh retains its flavor when preserved. It is an important fish in North America and Asia.

Pink, humpy

Oncorhynchus gorbuscha

Freshwater life: a few days

Saltwater life: 16 to 20 months

Average weight: 5 to 6 lb.

Range of weight: 1 1/2 to 12 lb.

Pinks spawn as two-year-olds and are found in North America and Asia.

Chum, dog

Oncorhynchus keta

Freshwater life: a few days

Saltwater life: 1/2 to 4 years

Average weight: 8 to 9 lb.

Range of weight: 3 to 35 lb.

Japan utilizes this fish in their extensive salmon culture program.

Coho, silver

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Freshwater life: 1 year

Saltwater life: 1 to 2 years

Average weight: 7 to 8 lb.

Range of weight: 1 1/2 to 30 lb.

Coho salmon are very strong swimmers and jumpers. The fish tend to spawn in coastal streams but have been successfully transplanted in the Great Lakes, Peru and New Zealand. It is not common in Asia.

Cherry

Oncorhynchus masu

Freshwater life: 1 year

Saltwater life: 1 to 2 years

Average weight: 7 to 8 lb.

Range of weight: 7 to 20 lb.

Asia is the only area these fish are found.

©1986 Natalie Fobes

Natalie Fobes, photographer on leave from the Seattle Times, is chronicling the Pacific Salmon and their struggle to survive.