This article, by APF fellow Nina Strochlic, first appeared in the Noēma Magazine on February 21, 2024. It was supported by her research for her APF fellowship.

Somaliland’s poets have toppled governments and ushered in peace.

It was a dark February evening when a young Somali math professor posted a poem on his Facebook page. In keeping with the tradition of his ancestors, who maintained an oral culture until only recently, he spoke it aloud in a rhythmic cadence:

“When I realized

there is neither

wells dug for you,

nor rescuers on the way

and the leaders elected to serve the nation have corrupted the resources;”

Then he uploaded the recording to his profile.

In Somaliland, poems were often recited to pass the time by men leading camel trains and by women weaving mats to cover their domed huts. Like the lives of the nomadic people who spoke them, the poems were cyclical. When their speakers moved, they brought their animals and their poetry. At each stop along this annual migration, the women would reuse the verses as they built their thatched homes and the men would recite them as they moved their herds to water.

But poems also served a utilitarian, public purpose: they could be deployed to argue a court case or to make peace between warring families. And their lines were powerful in ways few other nations could understand. In Somaliland, an autonomous region perched at the northern tip of Somalia, poetry had sparked wars, toppled governments, and offered paths to peace.

The math professor’s voice layered over a picture of him on a blustery beach, continued:

“when I witnessed

MPs who were expected to work for the nation,

fear Allah,

and sympathize with vulnerable people,

those when he needed them

gathered under the hot sun [to vote for him];

he forgot their rights

when he reached his goal,

failed to keep the pledge

and became a businessman

who [sells] his dignity

and your [natural] resources”

Xasan Daahir Ismaaciil wrote poetry in his spare time under the name Weedhsame. And as he spoke this poem, on that night in 2017, he didn’t yet know he was adding his name to a roster of poets revered in his country as modern sages. He didn’t know he was starting a poetry debate, or that this debate would shake the nation.

“this poem of worry

like a [song] for lambs

this poem that moans

responsibility tells me to recite –

and circumstance tells you to listen.”

By the time he was done, the poem was more than 300 lines and the video stretched more than 10 minutes long.

When Weedhsame started writing poetry as a teenager, he felt like he was releasing something that had always been inside him. His first poems were about love, though he didn’t have a girlfriend. He was drawn to the rhythms more than the words. But when he began writing about corruption, taxes, mismanagement of resources and nepotism, the words flowed. Such a shift wasn’t strange — poems and politics intermingled in Somali society, and it was seen as a poet’s duty to write about the injustices they saw.

In Somaliland, there were many. There were those imposed by the outside world: The fact that few nations recognized the tiny, autonomous sliver of land meant its people were largely cut off from the world’s institutions. The isolation had officially begun in 1991 when a civil war separated Somaliland from Somalia. But really it was a retreat back to a border drawn by British and Italian colonists in the 1880s, when they created British Somaliland and Italian Somalia.

After the war, when Somaliland gained partial independence, the injustices were less visible, but they had not stopped. People complained about corruption, nepotism and repression. Foreign aid money flowed into politicians’ pockets and hardline religious leaders stifled the music and theater that Somaliland had once been known for.

Weedhsame saw examples daily, and so, when he began writing poetry, he did what generations before him had done: he looked around. His early poems on corruption didn’t get much attention when they were first published, but years later, Weedhsame told me, they’d be memorized by a generation desperate for someone to speak their truth.

Poetry As Politics

No one knows when the first poetry debate was held in Somaliland. For generations, poetry had been woven into every facet of life.

The poetic guidelines that have lived in the heads of Somali poets could fill an encyclopedia. There are styles for love poems and styles used for nationalist verse during the independence struggle; there are styles to be accompanied by the oud, a stringed instrument from the Middle East; and a shorter, faster meter reserved for women.

In the 1850s, when British explorer Richard Burton visited the tip of the Horn of Africa, he was amazed to find that every Somali chief had a private poet, dedicated to praising his leadership and defending the clan’s honor. “It is strange that a dialect with no written character should so abound in poetry and eloquence,” he observed in what’s now Somaliland. “The country teems with ‘poets, poetasters, poetitos, and poetaccios:’ every man has his recognized position in literature as accurately defined as though he had been reviewed in a century of magazines.”

Over the years, the Somali people tested 18 different writing systems, but history and culture continued to be passed down orally, memorized in songs, poems and plays. It wasn’t until 1972 that a formal written form of the Somali language was standardized.

For more than a century, Somaliland had suffered under colonialism, dictatorship, civil war and economic collapse. Sometimes tensions became so taut that they seemed to explode into verse. Although journalists were often stifled, poets could more freely air their grievances publicly and watch them spread. One poem might spark another, then another and another.

When a debate — known as a silsilad or “chain” — was in full swing, poets near and far could weigh in with verse of their own. They’d recite their contributions publicly, relying on the listeners to memorize and spread the poems. Later, technology allowed them to record their contributions on cassette tapes and send their voices into the diaspora, where they’d be copied and shared.

It had been many decades since Somaliland’s last poetry debate — a multi-year affair that some say set the stage for the toppling of a dictatorship — when Weedhsame posted his poem on Facebook.

In 2017, the Somaliland parliament was considering whether to allow the United Arab Emirates to build a military base in its port city of Berbera. Weedhsame watched in shock as the measure seemed to have passed without debate. He wondered: had money traded hands to make that decision?

Feeling frustrated and powerless, he thought of his own children and their future and he began to write. His poem, “Plaintiff,” imagined a courtroom drama in which he held the government to task for corruption.

Unlike poets of the past, he didn’t hide behind allegory or metaphor. “Plaintiff” was the most direct verse he’d ever written: as a mathematician, he loathed making statements he couldn’t prove, but to him, this vote had crossed the line.

Weedhsame knew a poem could harness emotion in a way other forms of protest could not. Even so, he was shocked when it went viral. He’d been venting his frustrations, unaware that thousands of Somalis across the world felt the same way. As the number of views crept up by the tens of thousands, people from Canada to Abu Dhabi commented on his post. Presidential candidates, opposition party leaders and parliamentary leaders began calling, some to garner goodwill, others to complain, some to threaten or to attempt to bribe him. He couldn’t walk or drive down a road without hearing shouts of congratulations, and his phone would not stop ringing.

In the United States, his friend, the poet Cabdullaahi Xasan Ganey, saw the poem and decided to reply. In the courtroom Weedhsame had set up, he would be a witness to the charges made by the plaintiff. In a long poem he wrote of how the country had been betrayed by its politicians:

“The oppressed person said:

‘No matter how bitter,

the truth is necessary:

[you] sell the airports

put the ports on sale,

export all the minerals,

or are the brokers;

[you] disorient the youths,

sell them to smugglers.

By Allah you have endangered yourselves;

you are without conscience.’”

A debate must have at least two sides, and soon another poet entered, taking the government’s defense, and calling Weedhsame and Ganey traitors who denied their country economic development. Daaha Cabdi Gaas wrote:

“In my mind and spiritual heart

it seems that the poets were told

that the purpose of poetry

is to unfairly attack [the government];

do you know that is a tragedy

and trouble [to use poetry]

like a sharpened saw”

Then another poet weighed in, imitating a judge ruling in favor of Weedhsame. Soon reactions were being recorded and added as comments onto his post. Weedhsame had resurrected a tradition that stretched to his poet forefathers: he’d launched a poetry debate.

Somali poetry is almost always metrical and alliterative, with verse revolving around a certain letter. “Plaintiff” used M, and others would have to follow this structure, giving a name to the poetry debate it sparked: Miimley, or, “The one in M.”

While other chains were slow and steady, dependent on the cassette tapes traveling across the Somali diaspora, this was instant. Over the next two months, Weedhsame acted as the clearing house for poems: scanning them to avoid mentions of ethnic rivalries, before posting the latest responses to his Facebook page.

“We adopted poetry as our language that transmits the fatal and important issues,” says Weedhsame. “We are still an oral society. We depend on the words recited by our poets.”

Inside the archive room of Radio Hargeysa. (Mustafa Saeed/Noema Magazine)

The Cassette Tapes

When Radio Hargeysa launched, in 1941, there was nothing to feed its airwaves. Somali poetry and music had rarely, if ever, been recorded, but the need for radio programming changed that. That year, scholars believe Somali poetry was put on tape for the first time, and even before playing songs, the station aired poetry.

The archives of that radio station — one room of floor-to-ceiling shelves in the city’s downtown — is effectively an archive of Somali history. When civil war arrived in 1988, radio operators scrambled to preserve it by smuggling tapes out of the city or burying them in tunnels beneath the station. After the war, the new Ministry of Information set about collecting every cassette tape in town. Today, those 5,000 thousand tapes are the most comprehensive historical repository held by the Somaliland government.

The Hargeysa Cultural Center, however, set about collecting every Somali tape in the world. Tapes line the walls of the center, where the archivist is a 21-year-old college student named Hafsa Omer. Omer juggles studying psychology, playing on the local underground women’s basketball team and cataloging the poems and songs of her forefathers.

In the Somaliland Omer grew up in, war is the main narrative. Its neighbor, Somalia, was long regarded as a failed state by the international community. In Somaliland, there are few opportunities for cultural production and even fewer venues to experience it. But listening to these tapes opened Omer’s eyes.

“I had this idea in my mind that Somalis weren’t smart, that they couldn’t initiate something,” Omer says. She changed her mind when she heard the poetry debates that had shaken her parents’ generation. “They were thinking about us… They were imagining how the world looked in two or three generations.”

From an online archive she’s spent years organizing, she pulls up a recording of one tape. It opens with a poem, then the smooth meter of a talk-show host: “It’s me Xasan Mohamed, interviewing Yusuf Shaacir, talking about the poems of the Siinley…”

Shaacir, a poet, had memorized every poem of the Siinley, or, “The one in S,” a debate in the early 1970s. He told its story interspersed with lines of verse he knew by heart. Siinley hadn’t been planned as a debate, he said, but had sprung naturally from a song in a play written by a playwright named Cabdi Aadan Xaad, known as Cabdi Qays. In it, Qays wonders where the afterlife is: in the stars, on the land, in the mountains?

The song stirred something in Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame, a poet known as Hadraawi, the revered father of Somali poetry. Since 1969, Somalia, which then included Somaliland, had been ruled by the brutal dictator Mohamed Siad Barre, who exercised authoritarian control through a system called “scientific Socialism.”

Hadraawi interpreted the afterlife Qays asked about as a search for freedom and justice — as an escape from repression. The song, he felt, offered an entry point to talk about the government, so he responded in a poem.

The poems bounced back and forth between Qays, who by then had moved to Djibouti, and Hadraawi, in Mogadishu, Somalia. Soon symbolism and allegory took over: “What I’m asking is: Is tendon a meat? Is charity wealth?” Qays asks in one. “Is the middle finger equal to the thumb?” He speaks of a story their mothers told them, about a camel with a house on top of it. He asks whether moans of pain could be a song. Soon, 20 poets had joined in, from Djibouti, Mogadishu and Hargeysa, offering their own cryptic takes on the state of the nation.

There had been poetry debates before: the Halac-dheere chain at the turn of the 20th century debated the ethics of hospitality between two clans. After nearly 10 years, eight poets had contributed poems to the debate. In verse, one of the participating clans was called out as greedy, leaving a lasting stain on their reputation. A few decades later, the Guba — or, “The One That Burns” — chain spanned two generations of poets over nearly three decades; it has been blamed for inciting two tribal wars. “The mouth is a sharp saw,” one of the debate’s poets later said.

But this was different. The verses of the Siinley were so cloaked in coded, symbolism-laden messages that few listeners understood exactly what the poets were talking about. Was it love? Was it politics? Was it a competition of who knew more words? Even some of the poets seemed to not grasp the subject matters they juggled. One contributor compared the poems to a sandstorm and confessed that he didn’t understand exactly what they meant. Shielded by metaphors, they circled the day’s hottest topics, like the unification of the Somali people into one nation.

It was jaantaa rogan — “a flipped shoe” in Somali — directionless. Twenty years later, the poets would meet at a conference in Djibouti and ask each other what their poems had meant. But despite the opacity, the dictatorship understood that a strongly worded poem could threaten its grasp on power, and soon banned the tapes.

On the taped radio program, the host chimes in, noting that despite the confusion, the government crackdown revealed the true nature of the poets’ verse: “A lot of people think that Siinley was the first open door to criticize the government.”

The government arrested Hadraawi, who spent the next five years in jail. But it was too late. Regular Somalis were listening to the cassettes under their beds and hiding them in the roofs of their houses before passing them on to friends. Those listening “were thirsty for somebody to say anything against the government,” the poet Shaacir noted in the radio interview. “What gives meaning to the poem is the communities who listen to it. And the communities interpret it as what they need…Siinley was whatever that person needed.”

And before long it opened the door for a poetry debate powerful enough to topple the government.

The Collector

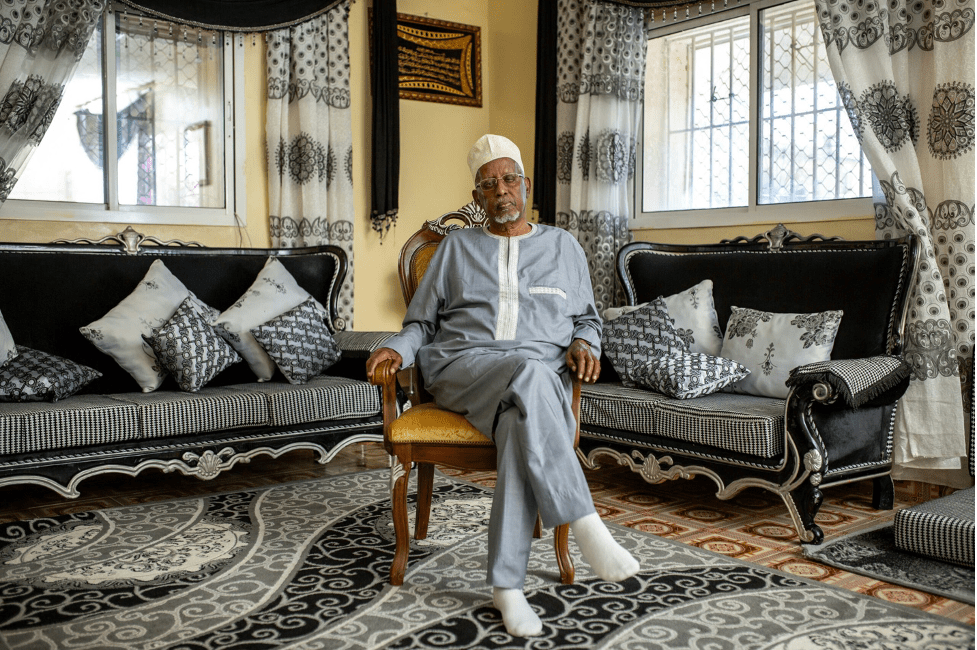

Gathering an oral history tradition is like chasing leaves as they fall from a tree. The painstaking task has fallen to Abdirahman Yusuf Ducaale, the unofficial chronicler of Somaliland. What he didn’t collect in the years he helped fight the civil war, which began in the 1980s and ended with Barre’s fall and Somaliland’s partial independence in 1991, he gathered after, as a minister of information for its new government.

His home, on a quiet, sandy corner in Hargeysa, is filled with scraps of paper, news clippings, meeting minutes, photographs, cassette tapes, films — even the canes that once helped balance Somaliland’s leaders. This physical record provides a rough outline of Somaliland’s history.

Ducaale’s literary output fills a coffee table in his living room: books about famous poets and unknown poets, books on war and peace. Even now, he’s dictating his latest tome to a young student who comes to his house to type since, at 75, his own eyes have grown milky with age.

When Ducaale sets out to write a book he must start from scratch. To write a biography of his favorite poet, an illiterate farmer named Timacadde, he went from house to house, collecting verses memorized by those who lived in the poet’s hometown. He opens a YouTube video and sings along.

“With such a voice it penetrated into the ears of people,” he says. Each poet has a signature tune, and a poet without a strong voice might hire professional singers to ensure their words reach far and wide.

“We used poetry in the war, we used poetry in peace, we used poetry in fighting colonialism,” Ducaale says. “So from day to day it was changing.”

To write “Deelley: A Prophecy That Came True,” his book on Somaliland’s most important poetry debate, Ducaale tracked down every one of the dozens of poets who participated and mailed them a questionnaire. His findings filled 468 pages.

In 1979, this debate would change Somaliland forever. That year, a poet named Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac, known as Gaarriye, published a poem called “No Refuge is Offered by Tribalism.” Somali society revolves around sprawling family trees that descend from five major clans, which trace their roots back to two brothers. These allegiances fuel politics and conflict. In the late 1970s, Barre’s government wanted to counter the power of these tribal connections; it commissioned a debate and asked Gaarriye to initiate it.

Gaarriye’s poem, which in Somali begins with the word “Dugsi,” set up a chain of alliteration in the letter D. Some 50 poets would end up contributing their metered thoughts to the chain, which became known as Deelley — or, “The One in D.” Within six months, nearly 70 poems filled out the chain and the government had canceled its endorsement.

Unlike the Siinley debate a few years earlier, no one was hiding. The poems quickly turned against Barre’s government.

“For the first time, Somali people were talking against the regime in front of him,” Ducaale says. Apprehensive about imprisoning the poets, Barre organized an awards ceremony at the national theater. By giving out medals, he thought, the poets would understand the debate had ended. His plan failed, Ducaale says: One year later, the debate was still going. The next year, in 1982, the Somali National Movement was formed; it would become the main government opposition in the civil war fought at the end of the 1980s.

“It was almost the rehearsal of the armed struggle,” says Ducaale. “It was a test for the people to speak in front of the dictator, to criticize him.”

A New Nation Of Poets

Today, the old poets recall when poetry and politics conspired to build a new nation. After three brutal years of civil war, the dictatorship ended and Somaliland disentangled from Somalia to form its own government in 1991. Poets gathered to help, settle the old rivalries and find a path toward peace. There were around 10 of them, known as the reconciliation poets.

Today, Jamac Cali Xassan, known as Gaashaan-cade, is grey-haired and walks with a cane. He recalls the days when traditional leaders gathered to elect the first president, and the poets gathered and recited poetry. They were beloved. Politicians would invite Hassan to their homes and tapes of his poems were sent to Somalis living abroad.

After, when the official reconciliation conference ended, he was asked to stay and record cassette tapes. For more than two months he sat in a room reciting his poems from memory onto individual cassettes, sometimes up to 10 at a time. “Poetry is what tells us who we are, it is our literature, it’s our culture,” he says. “I want people to use this culture.”

Somaliland’s poets are torchbearers with a hefty social responsibility. Now in his forties, Weedhsame knows that few people pay attention to the lessons of history. In his culture, this information still gets passed down in layers of verse: people turn to poets to analyze their society, to reveal what’s hidden.

“Every poet is some kind of politician,” Weedhsame says. “They don’t have a political position but they’re voices for society.”

Weedhsame’s predecessors hoped their poems would spread naturally by cassette tape. Today he posts his poems to his 314,000 Facebook followers. By writing them down, he’s veering away from the oral tradition but also preserving it. And his followers are listening.

By the end of the Miimley debate, more than 90 poets had contributed some 120 official and unofficial poems. It had drawn more poets and poems than any other debate and in record time. Around six months later, Somaliland voted in a new president. The candidates debated corruption, national resources, international recognition — issues that had been stirred by the poetry debate. Muse Bihi Abdi, who would go on to win the election, even came to speak with the poets about their criticisms.

Weedhsame was pleased that they were recognized. “At least they saw that a young generation of poets can organize themselves,” he says. “They see we can influence the votes of people.”

Though he believes the corruption he railed against still infects politics, he knows the debate was a reminder that politicians can’t overlook poetry. Poets have long been able to get away with criticism that others might not, but cloaking their opinions in verse hasn’t always protected them. Under Barre’s authoritarian rule, some poets were arrested and a few were killed. Others took government money to stay quiet or toe the party line.

“This is a medium that, crucially, lets people say things they might not otherwise be able to say,” writes Christina Woolner, a scholar of Somali poetry at the University of Cambridge, in her upcoming study of the poetry debate, “and that in so doing makes space for a deliberative reckoning about the present and future of Somaliland’s democratic sphere.”

Each generation arrives with a new take on the old ways, down to the length of the lines and the style of their meter. To capture shrinking attention spans, new poetic styles have become shorter and snappier. The words are changing too, as nomadic tribes settle into the nation’s cities and traditional dialects give way to a more uniform language.

But every new poem carries an oral culture into the modern world. In recent years, as Somaliland’s government cracked down on free speech, jailing multiple poets and journalists, their own persecution inspired the very thing the government hoped to quash: a small poetry debate. It was titled “Liinta xoorka leh,” so named for the beverage served to new inmates in Somaliland’s prisons — free-speaking poets and journalists among them. It didn’t last long, or make a splash like Miimley, but it was new and relevant. It was another rung in a time-honored tradition.

Strochlic’s reporting from Somaliland was supported by the Alicia Patterson Foundation.

Poetry translations courtesy of Christina Woolner, with input from Abdihakim Omer and Kenedid Hassan.