This article, by APF fellow Nina Strochlic, first appeared in the Washington Post on February 21, 2024. It was supported by her research for her APF fellowship.

POKLEK, Kosovo — Fadil Muqolli has spent more than two decades trying to rebuild his life. He remarried, raised two sons. “My new family,” he calls them. But there is no escaping his past when he lives a short walk from its charred remains.

Across the former Yugoslavia, poignant museums commemorate the wars sparked during the splintering of the six republics and two autonomous regions once held together by a fragile socialist bond. Bosnia has at least five museums about the war; Croatia has three. Serbia has one. Kosovo has none.

Earlier this year, nearly 25 years after war ended, the Ministry of Culture announced plans to develop one. For now, the history is preserved in privately owned sites, like the ruins of the home where Muqolli’s first family once lived. As memories fade, evidence of the war has survived only because Muqolli and other Kosovars safeguard it.

The night of April 16, 1999, plays over and over in Muqolli’s head.

At the time, Kosovo was a province of Serbia, with an ethnic Albanian majority and Serbian minority. When Albanian Kosovars launched a rebellion in 1998, the Serbian military and ethnic Serbian police officers carried out massacres that left some 13,500 people dead or missing.

That night, Muqolli’s parents, siblings, wife and four children had gathered for safety in the house that his father built in the village of Poklek. Muqolli left the forest where his unit of guerrilla soldiers was fighting to visit. They ate and talked until 2 a.m., when he stealthily returned to his position.

The next day, 53 people staying in the house were killed by grenades and bullets fired by uniformed police officers, witnesses later recounted. The structure was set on fire, and most of the bodies were reduced to bone.

‘It’s so painful’

Today, Muqolli, a soft-spoken man with cropped gray hair and wide hands, goes to work installing phone and internet lines, and returns each night to his new wife and sons, a few blocks from the shell of his old house.

He never considered tearing it down. For nearly 25 years, he has preserved it as a public memorial to his family and to the war. Walking up a stone path from the roadside, he travels back in time. At the end of the lane, trees sagging with plums nearly hide the tall house. “When I come here,” he said. “I see my family again.”

In the room where his family was killed, his voice drops to a whisper. “To visit this home is terrible,” he said. “It’s so painful even for a common visitor, let alone me, a father, brother and son.” A belt buckle, a child’s shoe, and bullet casings still lie in the rubble.

The responsibility of being a tour guide and caretaker makes him ill, he said. He has trouble sleeping. His thoughts are dark and depressing. But if he doesn’t do it, no one else will. “My children’s bones are here,” he said.

Just as Muqolli has reconstructed his life, Kosovo, too, has rebuilt. In 2008, nine years after a NATO bombing campaign ended the war, Kosovo declared its independence. A flood of international aid helped lay its foundation, and construction is everywhere.

Yet reminders of the conflict are unavoidable: War veterans march in the capital every few weeks, ensuring their sacrifices are not forgotten. Granite monuments to fallen soldiers dot cities and the countryside.

Even so, evidence is slipping away. “Why is there no museum to the war?” said Bekim Blakaj, the executive director of the Humanitarian Law Center Kosovo, which collects documentation of wartime crimes. “We will lose the narrative and the memory of what happened.”

In the dimly lit National Museum in Pristina, the capital, there is no account of the bloodshed, the destroyed cities, or the refugee crisis that displaced half the country. A rebel leader’s burned-out compound is preserved by the government, along with a small museum and a cemetery. But to learn about the civilian toll, a visitor must seek out Muqolli and the few others who have saved their own small pieces of the war.

Proof, evidence, testimony

In the small city of Gjakova, known for its dervishes of Islam’s mystical Sufi order, sits Kosovo’s most famous private museum: the Qerkezi house, a neat, two-story home adorned with a red-and-black Albanian flag.

Ferdonije Qerkezi lives alone now, but she once shared this home with her husband, their four sons, and two daughters-in-law. She slowly climbs the stairs to her sons’ bedrooms, where their beds, clothes, toys, and photographs are wrapped in plastic. Matching tuxedos hang in the wardrobe; her husband, a tailor, made them for their sons’ joint wedding.

Qerkezi sits heavily on a beige couch and launches into a history she has spent more than two decades reciting to visitors. It never gets easier.

“It’s beyond words to describe the pain and deep sadness of telling the story of how your family was taken away and murdered,” she said, her breathing labored. “I don’t know if there are words.”

On April 27, 1999, a Serb police officer came to Qerkezi’s house and took her husband and sons — the youngest was 14 — for questioning. Qerkezi waited for her family’s return and did not change a thing in the house. Every night, for the first two years after the war ended, she set a dinner table for six.

Word of her vigil spread, and visitors began to come: aid workers, dignitaries, even presidents.

In 2005, the bodies of her youngest and oldest sons were found in a mass grave in Serbia; her husband and other sons are still missing.

In 2008, the house was declared a museum by the municipality, but aside from free utilities and donated glass cabinets, Qerkezi gets no assistance. Asked why there is no war museum in Kosovo, she grew angry. “Why didn’t I do it on my own? It’s just because I can’t fit all war crimes in one house,” she said. “Why didn’t the state do it?”

At family-run museums across the country, proprietors repeat the same words to describe what they’ve preserved: “proof,” “evidence,” “testimony.”

Serbia has long denied wrongdoing and most families still do not know who was responsible for killing their loved ones. Some still hope to achieve justice in court.

Anne Gilliland, a professor at UCLA who has studied private museums across the Balkans, calls them archives. “The family members there are living documents themselves,” Gilliland said.

For a decade after the war, Kosovo was governed by a United Nations-appointed international coalition. “They were not interested in collective memory,” said Baki Svirca, a historian who is helping the government create an official narrative of the war. “They were much more interested in keeping the status quo and peace.”

Svirca has been studying war museums from North Carolina to Israel. He particularly admires how the Jewish community has memorialized the Holocaust, while using it as a tool for education. He hopes one day Kosovars can replicate that model.

Kosovo’s minister of culture, Hajrulla Çeku, said plans for one or more official museums will be drafted next year “to present a comprehensive history of crimes” but declined to comment on why previous governments did not start the task.

Disentangling fact from hatred

For now, those stories are being preserved by whatever means possible.

In the small city of Suhareka, a storefront pockmarked with bullet holes and scorch marks sits in a strip mall. The door is locked but there is a phone number posted outside, and soon a lanky, white-haired man appears jangling a key ring.

The man, Hysni Berisha, said this was a pizzeria, where 44 members of his extended family were shot and burned by Serbian forces. Their bodies were later unearthed from a mass grave in Serbia. The owner gave Berisha the shop and he left it as it was. Last year, with a donation from a local energy drink company, he encased the bullet-scarred walls in glass and built an elevated walkway over the rubble-strewn floor.

“I’ve never been interested in keeping this for the state, or the city, or myself,” he said. “My idea is to keep it for the next generations. Reconciliation might come but this should never be forgotten.”

In another country, he said, the site might have become a museum with a memorial park for reflection. Instead, it is squeezed next to a gaming parlor that echoes with clacks from a foosball table.

The bodies of some children killed here were never found, he said. Sometimes they appear in his dreams, asking if anyone is looking for them. “I have a lot of voices in my head,” he said.

When there is an official war museum in Kosovo, it will struggle to disentangle fact from hatred. Most of the war’s victims were ethnic Albanians, but Serbs, Roma, and others also suffered. Just as Serbia largely denies Kosovo’s accounts of the war, Kosovo often ignores these other victims.

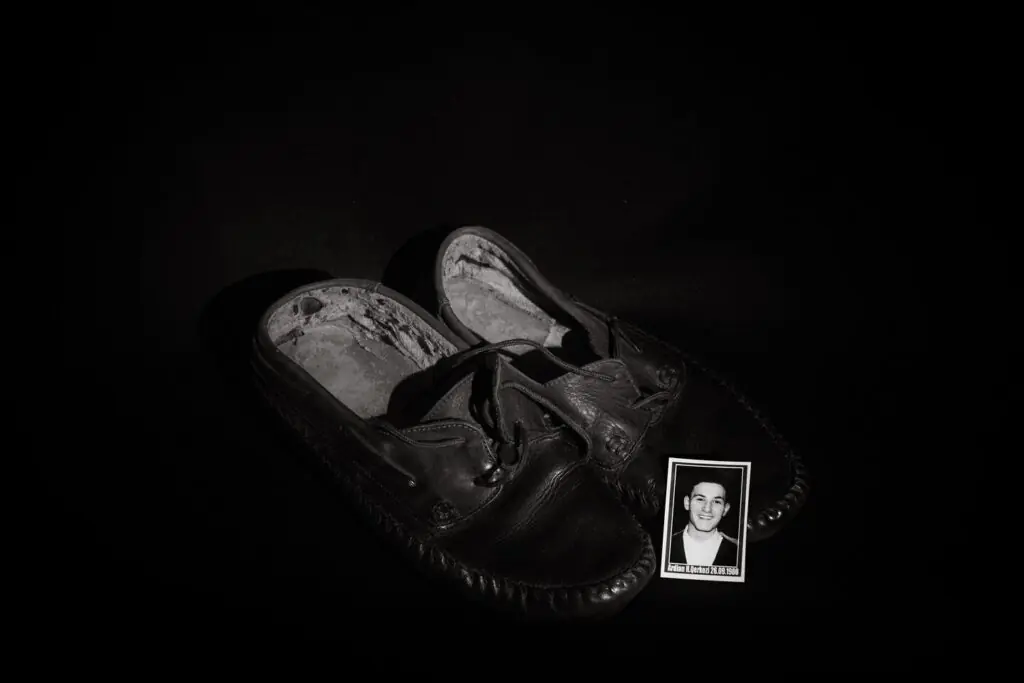

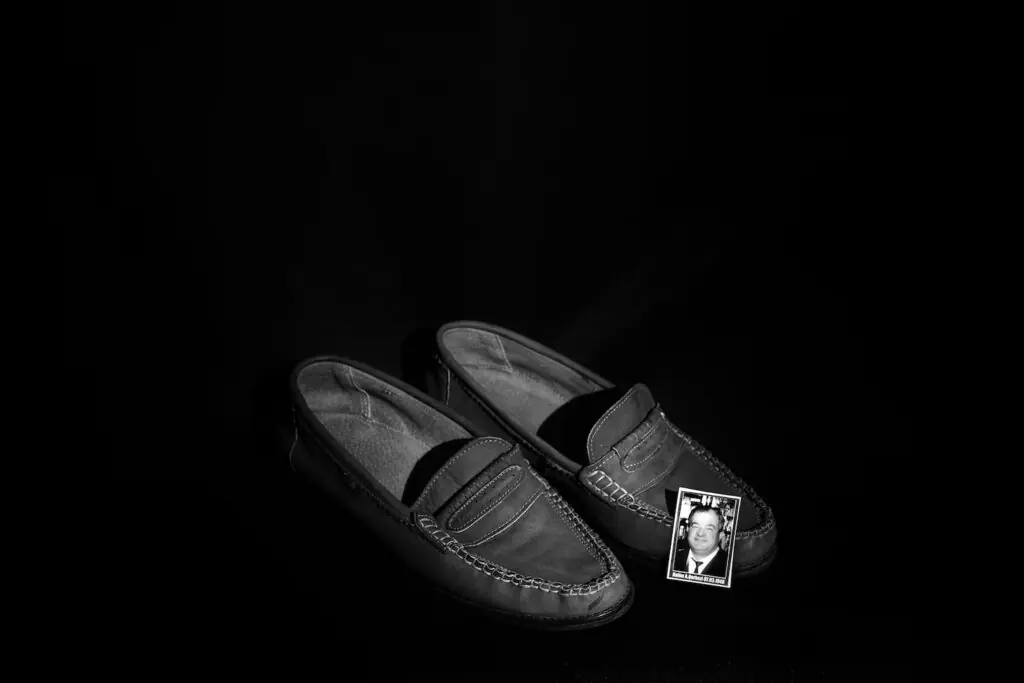

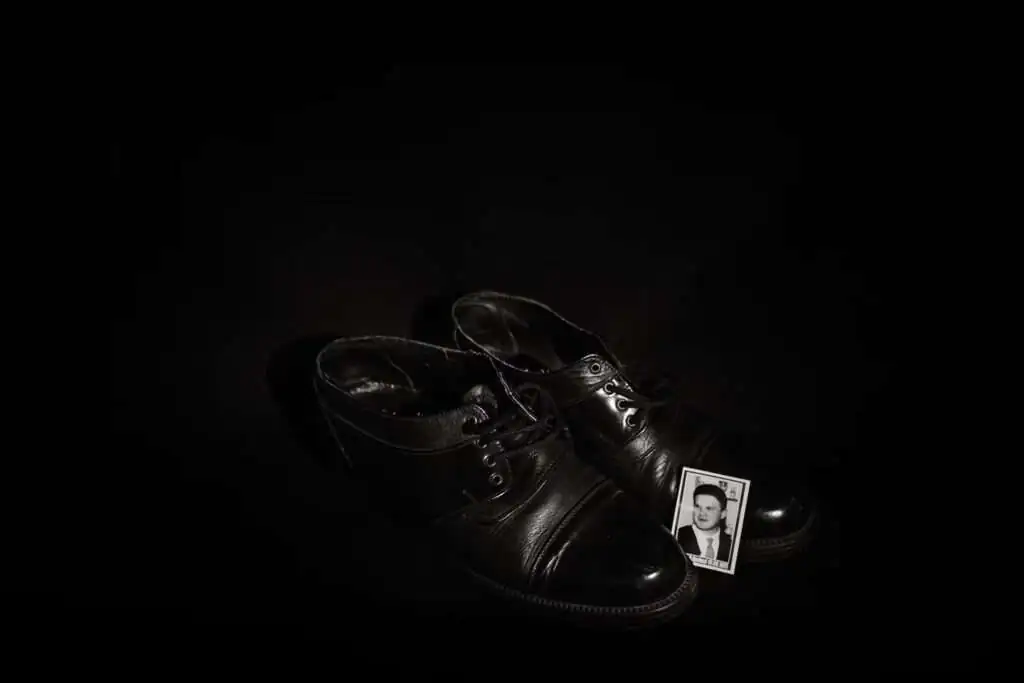

In the basement of a student library in Pristina, a wall is covered with the names of all 1,133 children killed or missing in wartime. Their clothing, toys, and books are displayed in glass cases by the Humanitarian Law Center, which has compiled a file for each victim.

Those stories led to an exhibit called “Once Upon a Time and Never Again,” which opened in 2019. It was meant to run for a year, but victims’ families kept visiting, bringing relatives and friends. The staff felt they could not close.

In one glass case are notebooks filled with the neat penmanship of Fadil Muqolli’s murdered children. Muqolli’s eldest “new” son is now 19, part of the first generation to grow up in an independent Kosovo. At times, Muqolli said he feels guilty that he started another family and burdened it with his past.

Recently, the government pledged to renovate his house and hire a docent. His son has begun helping at the museum. He hopes they both can step out from the war’s shadow but not forget it.

“This house,” he said, “is a piece of the new history of our country.”

Nina Strochlic’s reporting from Kosovo was funded by the Alicia Patterson Foundation.