RICHLAND, WA–Most people involved in safeguarding the U.S. nuclear industry from the theft or diversion of materials were barely aware until last year of the plant operated here by the Exxon Nuclear Company. Now they are paying much closer attention to the events unfolding at Richland.

For the first time, a U.S. nuclear facility is coming under the same international controls that are applied routinely to hundreds of other installations throughout the world. The procedures being implemented here are part of the controversial monitoring system that is supposed to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons by detecting the misuse of normally peaceful commercial nuclear facilities.

The adequacy of these safeguards and the effectiveness of the International Atomic Energy Agency which administers them increasingly are being called into question at the highest levels of the U.S. government. Congress, the State Department, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the National Security Council are all engaged in this ongoing debate, a process which is likely to reshape American policy toward the export of sensitive nuclear technology and materials.

At issue is a fiendishly complex problem in the assessment of technology: How will it be possible to maintain a dividing line between the production of nuclear power in developing nations and the production of nuclear weapons?

An Outpost in the War

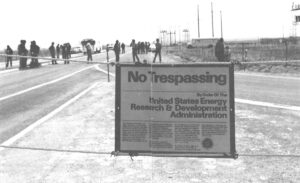

Only a small sign amid the tumbleweed at the side of the road about four miles north of town identifies the modest cluster of windowless buildings as the Exxon Nuclear plant. The neatly maintained complex occupies a shallow depression like an industrial oasis in the empty desert of southeastern Washington. Behind the closely guarded fences, Exxon Nuclear manufactures fuel assemblies for forty nuclear power reactors.

Dick Schneider came to work early on this cold December morning to complete the last-minute arrangements before the team of international inspectors arrived. Outside, the first rays of sunlight streamed across the dunes and illuminated the snowy crest of the low winding Rattlesnake Mountains. Most of this barren landscape was part of the government’s vast Hanford Reservation, site of the original top-secret reactors that produced the plutonium for the country’s first nuclear weapons.

Nearly a decade ago, Exxon had far-reaching ambitions to become a worldwide leader in the nuclear field. Executives envisioned a fuel-fabrication facility, a uranium-enrichment plant and a spent-fuel reprocessing plant to complement the company’s uranium mining operations. Such a complex would have established the firm as the first independent full-service supplier of fuel to the nuclear power industry, which seemed to be growing rapidly at the time.

Since then, the Exxon Nuclear strategy has run aground. At home, its aspirations were dashed by the reversal of government policies favoring reprocessing of spent fuel and the private ownership of enrichment facilities. Abroad, the company encountered increasing competition from European suppliers trying to expand their own nuclear capability. The only part of the grandiose plan that ever got off the drawing board was this small, highly advanced fuel-fabrication plant near Richland.

Earlier in the week, Dick Schneider had received an advance shipment of scientific instruments from Vienna. Now the soft-spoken physical chemist was checking the supply of liquid nitrogen that his visitors would need later in the day for the operation of their delicate radiation counter. For the next three days, the delegation from the International Atomic Energy Agency would be inspecting the plant using these instruments to verify the composition of its inventory of low-enriched uranium.

Inspectors Herminio Gonzalez-Montes, a Spaniard, and Pantelis Ikonomou, a Greek, would be auditing the inventory records. They also would be sampling, weighing and measuring a small portion of the more than 200,000 kilograms of uranium at the plant in various forms. The goal of the inspectors was to determine whether Exxon Nuclear’s stated balance was accurate within 2,000 kilograms.

This material could not be used directly to make a bomb However, 2,000 kilograms of reactor fuel would contain enough fissionable uranium for a weapon if it could be extracted from the fuel, a difficult process. Still, the verification procedure for this inspection would be the same as that which is applied to highly enriched uranium and other nuclear substances that pose a more immediate proliferation threat.

The World’s Nuclear Watchdog

The International Atomic Energy Agency (generally known as the IAEA) is a little-known arm of the United Nations established 25 years ago with heavy American backing.

Since then, it has become the backbone of the global system for managing peaceful nuclear development. President Eisenhower called for the creation of such a body in his famous “Atoms for Peace” speech to the UN General Assembly. In that address, he described an entity that would bring the envisioned benefits of nuclear technology to the rest of the world. At first, the IAEA acted primarily as a promotional organization, helping its member nations acquire nuclear power plants. From the beginning, the organization assumed a second function parallel to these developmental activities. The IAEA charter authorized the agency to establish a system of safeguards to deter the possible surreptitious use of nuclear technology and fissionable materials distributed under its aegis for military purposes–that is, to make nuclear weapons.

In the early years, however, the U.S. government reserved this watchdog role for itself in bilateral trade agreements with recipients of American nuclear technology. Gradually, more of the responsibility for safeguarding material was transferred to the IAEA. This policy of increasing reliance on the agency nurtured its growth and paved the way for its emergence as the official instrument of international control over nuclear activities.

The IAEA’s role as global monitor was finally spelled out formally in the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, a pact negotiated by the United States and the Soviet Union that went into effect in 1970. When nations that did not possess nuclear weapons signed the document, they received a promise of assistance from the major powers in the development of their peaceful nuclear programs. At the same time, they agreed not to acquire nuclear weapons and to open their facilities to surveillance by the IAEA in order to demonstrate compliance with the provisions of the treaty. Countries which already had nuclear weapons were exempted from the inspection requirement.

In the intervening years, 114 nations from Afghanistan to Zaire have ratified the pact. More than a dozen others that are not parties to the treaty still accept IAEA safeguards at a portion of their facilities. In all, the agency monitors 737 installations in 50 countries. Reportedly, this total constitutes about 98 percent of the known nuclear sites in the non-weapons countries. The IAEA now operates on an annual budget of $89 million with $25 million going to the safeguards program. But the larger share–$64 million–still goes to developmental and promotional activities.

The Politics of Looking for Diverters

Though the framework of international supervision is firmly in place, critics contend that the IAEA is not really able to do the job properly. Recently, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission concluded that the system “would not detect a diversion in at least some types of facilities.” Senator John Glenn, chief sponsor of the 1978 Non-Proliferation Act, feels it is “obvious that the system has considerable weaknesses.” The Israeli bombing of Iraq’s Osirak research reactor in June 1981 was widely viewed as a dramatic repudiation of the IAEA. The Iraqi reactor was safeguarded by the agency, but the Israelis were unwilling to risk their future on the IAEA’s vigilance.

The skeptics insist that the work of the agency is badly compromised by a multitude of practical and political limitations: an inadequate number of inspectors, troubling loopholes in the inspection agreements, unreliable and imprecise equipment, slow reporting and analysis of data, and the lack of authority to follow up on suspicious activities.

Ironically, the recent extension of IAEA safeguards to the Exxon Nuclear plant illustrates the sort of political complications that compromise the effectiveness of the agency. At the same time, the situation demonstrates the unusual steps that the U.S. is taking in order to beef up the IAEA and build a viable institution for policing nuclear activity.

Obviously, the United States is not an aspiring candidate to the nuclear fraternity–it is a charter member. A trickle of undetected material flowing from the Exxon Nuclear plant to a clandestine American weapons program would hardly represent a serious new proliferation threat. Just up the road, the Department of Energy (and its predecessors) have been producing plutonium for thousands of U.S. warheads at the Hanford N-reactor for years. The department is preparing to reopen its mothballed plutonium-purification plant to speed the manufacture of thousands of new warheads.

The IAEA inspectors are here more for reasons of international economics and long-term diplomatic strategy than safeguards. In discussions surrounding the Non-Proliferation Treaty, technologically advanced countries like Germany, Japan and Italy expressed their fears that the additional expense of complying with IAEA requirements would penalize their nuclear export business to the advantage of their American competitors. Like a parent swallowing a spoonful of medicine to demonstrate its palatability, Lyndon Johnson offered to open America’s commercial nuclear industry to the same inspections. (Johnson’s offer was conditional upon full implementation elsewhere, hence the long delay.)

Now this concession to equal treatment is causing new problems. Full-scale IAEA inspections here would divert the scarce resources of the overburdened agency from non-weapon states where close scrutiny is essential. For the moment, the monitoring is being applied very selectively in the U.S. All commercial facilities will comply with the IAEA’s paperwork requirements, but only three are actually being inspected. (The other two are the Trojan power plant near Portland, Oregon, and the Rancho Seco power plant near Sacramento, California, both chosen for their very rough proximity to Richland.) The inspection burden will be rotated in the years ahead.

This solution also has its drawbacks. Some of the Europeans are suggesting that they would appreciate a similar relaxation in the inspection schedule.

The IAEA is trying to put the best possible face on the situation. Though no proliferation is being prevented by the Exxon inspections, the exercise gives the agency a chance to become familiar with the advanced technology and highly computerized accounting systems that are likely to become more common elsewhere. The IAEA is also gaining useful experience in monitoring a bulk-handling facility where materials are available in loose forms.

The spread of large bulk facilities like reprocessing and enrichment plants is generally considered to constitute the most serious proliferation threat at the moment. Plants like these handle substantially larger quantities of nuclear material than can be found in power plants and therefore entail a greater risk of diversion. Measurement of liquids and powders in these bulk facilities inevitably involves a small margin of error that could mask shortages; unlike bulk facilities, power plants have sealed fuel assemblies that can be counted exactly. At best, safeguarding these bulk facilities is still an imperfect and uncertain process.

Good Intentions go Awry

The solution proposed by critics of the IAEA is to tighten restrictions on the export of nuclear technology, especially the large bulk-handling plants. Unfortunately, a crackdown on nuclear trade also poses serious problems. In the complex world of international nuclear diplomacy, relationships are often strangely inverted. Well-intentioned actions frequently turn out to have the opposite effect.

Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter attempted to stem the trade in nuclear technology. Later, Congress tried to legislate stricter controls on exports. Their efforts were self-defeating. The U.S. quickly gained a reputation as an unreliable supplier likely to back out of a deal or attach unexpected conditions.

Many poor countries dependent upon energy imports have tended to view nuclear power as their only hope for achieving self-sufficiency. As OPEC prices soared, their pursuit of the nuclear-power option became more urgent. The slowdown in U.S. exports clouded these plans. The developing countries look upon their nuclear suppliers the same way Americans view OPEC–as another foreign threat to be circumvented. Consequently, attempts to restrict U.S. nuclear exports actually have increased the determination of poor countries to build their own nuclear industries and become independent of all foreign energy suppliers–OPEC and the U.S. The result has been more pressure from third-world countries within the IAEA for the relaxation of safeguards and for stepping up assistance to their nuclear industries.

The Reagan Administration’s emerging nonproliferation policy is based on loosening export restrictions in order to reestablish the U.S. as a reliable supplier. The theory is that, through trade agreements, the U.S. may be able to influence the use of the facilities and materials it sells. The Administration may be able to buck up international support for the IAEA and buy time for the agency to improve its techniques.

An International Milestone

Meanwhile, the agency continues to look for methods of applying its safeguards more economically and effectively. The inspections at Richland so far have yielded several improvements in technique and reductions in cost.

Dick Schneider and his supervisor, Roy Nilson, have presented papers on their experience with IAEA to attentive audiences at professional and trade meetings and have described a couple of small but financially significant innovations that have been adopted by the IAEA. At this stage, that’s about all that can be hoped for. The inspections at Richland are not likely to produce any dramatic breakthroughs–only a series of small refinements that tighten the overall system by making it more accurate, politically acceptable, and cheaper to administer.

Nilson has concluded that the expense of complying with IAEA requirements–a serious problem in some countries–eventually may be as low as 0.15 percent of the cost of fuel fabrication. Certain European suppliers are complaining that the IAEA safeguards add as much as 10 percent to their costs. If Nilson is right, the price of safeguards can drop to an insignificant fraction of the cost of electricity produced by a nuclear power plant.

The IAEA does not announce its findings publicly so there has been no official judgment on the adequacy of Exxon’s material handling. If the agency detects an unexplained discrepancy or evidence of possible diversion, its only recourse is to notify the United Nations. Ideally, the members would invoke diplomatic procedures to deal with the offender. Schneider and Nilson say that the measurements by the IAEA inspection team that they observed correspond very closely to the companies own figures so there should be no problem.

After a farewell luncheon for the foreign visitors at the local Holiday Inn, Dick Schneider offered a personal thought on the IAEA. Despite its possible shortcomings, the agency has managed at least one remarkable achievement, he explained: the limited suspension of national sovereignty by the participants. Never before have nations willingly opened their affairs to even this much outside scrutiny. The “amazing accomplishment” is just that countries are permitting internationally supervised inspections.

©1982 Ron Wolf

Ron Wolf is investigating the safeguarding of nuclear materials in the U.S.