MERCED, Calif.–One hand rises slowly into the air from the back of a room overflowing with Southeast Asian refugees. Another hand pops up in the front. A third hand timidly reaches upwards. The other 200 refugees in the bare room do not raise their hands, unable to say they have jobs or know someone who does.

Outside, a winter rain falls on Merced, California, a small city in the rural San Joaquin Valley, where 30,000 Southeast Asians have moved since 1981. Ninety percent of the refugees are unemployed, subsisting on public welfare and food grown in community gardens. They are Hmong refugees from the highlands of Laos, organized by the U.S. CIA during the Vietnam War to fight North Vietnamese and Lao communists. They are unskilled, unsophisticated in American life and living on the bottom of the economic ladder, untrained in how to climb the economic rungs.

At the front of the room sits Dang Moua, director of the Hmong community association in Merced. Dang Moua is one of a small group of Hmong who have begun to master the U.S. economic system. He is trying to show the rest how to chart their way to the American dream.

The same scene is repeated throughout California, Wisconsin, and Minnesota where more than half the 70,000 Hmong refugees in this country live. The Hmong, and a few smaller groups of refugees from the highlands of Laos, have presented refugee resettlement officials with a sour legacy of the Vietnam War. Their strong support of the U.S. cause in Southeast Asia earned them the right to a new life here; but they have few of the social and economic tools necessary to build that new life.

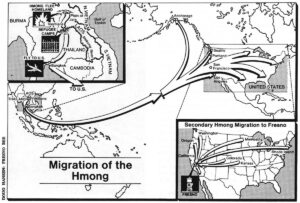

Their history is of little help to them. For thousands of years they were a migratory tribe, moving south from China to Vietnam and Laos. Their life was simple, the skills necessary to survive were few. Brought to the United States with nearly 700,000 other Southeast Asians, the Hmong had lost everything in the war but their iron will to survive. For the past decade they have floundered in the United States, bouncing from community to community, coast to coast, depending on social welfare and government-funded vocational training to learn new ways to survive. Liberal public assistance has drawn more than half of the Hmong to Wisconsin and Minnesota and California, where many fear their dismal condition will fester.

But if attention is shifted away from the masses of Hmong unemployed, pictures of success are beginning to emerge. If the change is measured in small increments, change is coming for the Hmong. In small enclaves and tenuous economic development programs, experiments in blending Hmong experience and American technology are beginning to grow. Even in the midst of the San Joaquin Valley, where welfare dependency is now entangling the next generation of Hmong, a few fragile attempts are being made at self-sufficiency.

It is shortly after dark as the headlights on Dang Moua’s van sweep across a wide stretch of farmland north of Merced. The lights fall on an irrigation ditch as the van drops into a muddy puddle, then the beams come to rest on a low sheet-metal building as the vehicle rolls to a stop. Inside, a chorus of primitive grunts echo into the night. Dang Moua motions for everyone in the van to remain seated. Everything goes black as he shuts off the lights and walks into the building. Suddenly it is swathed in light and the grunting reaches a feverish pitch. Dang Moua motions towards the building and, inside, hundreds of hogs race towards him, stumbling over each other to reach the feeding bins.

Dang Moua moved to the San Joaquin Valley in 1979, one of the first Hmong refugees to do so. He had saved some money and used it as a down-payment on a farm, where he built a barn and slaughtering room and started a hog farm, knowing that other Hmong coming into the valley would need his product because their diet is heavy on pork. His predictions were correct and now, “I have a bigger market for the pigs than I can supply,” he said.

His logic is simple and clear, and in keeping with the thinking of immigrants who have come before him. He used knowledge brought from Laos to provide a service to his fellow refugees. He learned a few hard lessons along the way about financing, agriculture and marketing. In one instance, after he poured the concrete slab for the slaughtering house, the building inspector told him to rip it up because he had not reinforced the floor with steel.

“You know, back home, we butcher a pig outside on the ground,” he said, “Here you have health inspectors, building codes, many problems.”

The greatest problem is that most Hmong skills are not appropriate in the American economy. In Laos they were simple farmers who would burn a section of jungle and let the ashes nourish rice, vegetables and their cash crop, opium. This type of agriculture–called “slash and burn”–is simple, but inefficient, environmentally disastrous, and illegal in the United States.

Dang Moua’s experience has been repeated across the country. But like his experience, many of the projects begin in fits and starts, each a learning experience in the American way.

Unlike many Vietnamese refugees who came to the United States as skilled businessmen, doctors, teachers and fishermen, the Hmong had no experience in business The first attempts at economic development for most Hmong in their 30s and 40s came when they arrived in the United States after a decade of full-time soldiering in Laos. The concept of self-improvement for Hmong in the hills of Laos meant growing more food on free land, breeding healthy hogs and harvesting larger crops of powerful opium.

“There is something fundamental that I have found working with the Hmong. That is that they must go through (a project) once, then they can do it themselves,” says Jane Kretzmann, the state refugee coordinator for Minnesota, where 10,000 Hmong live, largely in the twin cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul.

But, she admits, often the fault lies with Americans who bring patronizing feelings along with an honest desire to help.

“In working with the Hmong, we Americans always try to do it our way. The Hmong way has to be the second time around,” Kretzmann lamented recently.

But before 1983, the vast majority of Hmong did not know how to do it themselves, even when it came to getting an entry level job as a janitor or maid.

In February, 1993, Dang Moua and other Hmong leaders from around the country were brought to Washington, DC, to meet with federal officials and representatives from private industry to search for answers to this Hmong economic quagmire.

No one thought the Washington meeting would be the start of something big; they were looking for the start of something small. But the meeting signaled a growing awareness of the intractable resettlement problems of the Hmong. The meeting was organized by the Indochinese Resource Action Committee and Carol Leviton, the seemingly tireless projects coordinator for the Hmong/Highlander Development Fund, a private loan guarantee fund for Hmong development.

“I think the government looked at the meeting as bringing together the ‘Indian Chiefs’ to tell them it was time for them to get going on their own,” says Leviton, one of a small cadre of former Peace Corps volunteers and U.S. government employees in Thailand who are now helping Hmong refugees recover their independence.

But the Hmong leaders had an agenda of their own.

On top of the list was fear over proposals to cut off social services to the refugees after they had been in the country for 18 months; too short a time, they said, for an illiterate mountain man to learn English and vocational skills. Next on the list was deep concern over the constant bouncing back and forth around the country of thousands of Hmong looking for redoubt from unemployment, tough inner cities and isolation from other Hmong.

The federal government was concerned about the constant movement of Hmong also, but was more concerned about the concentration of Hmong in California, Wisconsin and Minnesota, a growing political problem because of the drain on state and county budgets.

If the goal of the meeting was to prepare the Hmong for an end to government support, the reality of the desperate situation facing the refugees derailed that plan. The leaders outlined a bleak future for the Hmong if they were not somehow stopped from moving constantly around the country, ever closer to the Central Valley and Wisconsin, where thousands of Hmong already lived, destitute and futureless.

After the Washington meeting, the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement announced a plan to stabilize the Hmong population and keep more of them from moving to California. The government put $3 million into a campaign called the Highland Lao Initiative, aimed at bolstering social services in communities that were losing Hmong residents.

The program funneled money for 47 welfare and vocational programs for the Hmong in 44 cities outside of California. While 60 percent of the Hmong had been settled in or moved to California by the time the project began, 31,966 lived in cities in the Midwest, Northwest and Northeast.

During the time the project ran–from September 1983 to September 1984–the Hmong population in 15 of the targeted cities fell by only 436: from 15,302 to 14,866. The 36 families in Syracuse, NY, remained there and the populations of seven other cities in the program grew. Four Wisconsin cities included in the study grew a total of 1,054. Arrivals in Fresno, CA, the target of much Hmong migration, rose from approximately 10,000 to 13,000, but the rate of increase slowed.

While the results of the Highland Lao Initiative were not stunning, it outlined the framework for other projects that now hold the tenuous possibility of nudging the Hmong closer to the mainstream. The theory was, and still is, that the Hmong must be kept from concentrating in California, where unemployment is high and generous welfare benefits are a disincentive to work. To keep Hmong out of California, states and the federal government must provide educational and vocational opportunities for the refugees elsewhere.

“Really what the Highland Lao Initiative was, was a way to get services to the Hmong that were not available to them during the massive influx of refugees into the country after the war,” says Toyo Biddle, of the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement.

“The Hmong were ignored when they arrived,” agreed Wells Klein, director of the American Council for Nationalities Services, one of the largest private resettlement agencies in the country. “We didn’t recognize they were so different from the Vietnamese, that they were illiterate and unskilled, so we had no special plans for them.”

Ten years after the Hmong began to arrive, things are beginning to change.

With continued support from public assistance, Hmong are starting pilot projects, using what they know, to supplement their income and develop economic strategies for self-sufficiency. It is a gamble, but officials see it as a small but necessary step to fight unending welfare dependency. The projects are not the answer to the problems in the San Joaquin Valley, where too many Hmong, too little money, and too few jobs add up to a bleak future. But as one official said recently, “The person who finds a solution to the problems in the valley will be a certified genius.”

In Wisconsin, Hmong in five communities are learning about the American economic system through cucumbers.

What began as a local gardening project in Eau Claire, WI, has turned into a business for half a dozen Hmong communities throughout the state. In Eau Claire, Hmong refugee Yer Vang gathered $700 together from the Hmong community there and started a pickle cucumber farm. He arranged for technical assistance from the University of Wisconsin and for land from the county agricultural extension. The first year, 24 families working the land earned $23,000.

The idea spread and there are now Hmong pickle projects in Milwaukee, West Bend, Chippewa Falls, Eau Claire and two projects in Wausau. Each project has a buying agent and they contract their cucumber pickles to Gedney Pickle Co., of Minnesota.

“These projects are not really meant to get the Hmong off assistance,” says Susan Levy, of the Wisconsin State Refugee Office, “But it supplements their income and teaches them important lessons about American economics.”

Another offshoot of the Highland Lao Initiative was a project developed at the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement to draw Hmong away from California and Wisconsin with the promise of employment and the chance of bettering themselves. The project–called Planned Secondary Resettlement–pays for Hmong families to move from California and Wisconsin, and other highly impacted areas, to towns where Hmong are beginning to thrive.

Secondary resettlements are being planned in Dallas, Atlanta and the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, where small Hmong communities are experiencing nearly full employment and other benefits from living in areas where the cost of living is low and entry level jobs are available for non-English speakers.

“One reason why (the Dallas community thrives) is because of job opportunities there. Another factor is that at least half of the community was relatively skilled. They came to Dallas after they had received training in areas where they could not get a job,” Biddle says.

Thriving Communities

“That community was pretty careful about saying to other people who might come to Dallas that it was a good place for Hmong who want to work and want to work hard, but it was certainly not a place where there would be welfare available,” she says.

Other thriving communities include the 36 to 40 families in Syracuse, NY, 1,800 people in Providence, RI, 129 people in Hartford, CT, and the 400 in Marion and Morgantown, NC.

In Providence, 90 percent of the Hmong are employed as machine operators, assembly workers, jewelry makers and sewing machine operators. There are also 80 students in college in Rhode Island, an historic step for the illiterate tribes of Laos.

“These are exemplary communities. Its not really exemplary projects that are as important as exemplary places for the Hmong, where they can get jobs, buy houses and send their children to good schools,” Biddle says.

“In places like the Valley or Wisconsin it is important to try all possible strategies…you can’t leave any stone unturned, you have to attempt whatever is available, whatever methods might possibly work to help these people,” she said.

In Dallas there is little talk of starting cooperative Hmong farms and self-help organizations, according to a study of Hmong resettlement done in 1983, because the Hmong there have jobs and houses.

But for those Hmong in California, Minnesota and Wisconsin who do not wish to pick up and move again, economic development programs are one of only a few alternatives to welfare dependency. Like novices in any economic endeavor, lessons for the Hmong can be expensive, especially when they pursue entrepreneurial projects rather than entering the job market for unskilled workers.

“The whole notion of an entrepreneurial person is rare with the Hmong. There are not many Hmong who are out there carrying on their own entrepreneurial project. Most of the economic development is group oriented. There is a lot more of that going on in the Highland Lao community than an individual entrepreneur striving to make himself rich,” says Carol Leviton, of the Hmong/Highland Lao Development Fund.

In Minnesota, an ambitious farming project, fueled by dreams and good will, fell apart when promised financial backing never materialized. The Hiawatha Valley Farm Project taught the Hmong more about finances and legal problems than it did about American farming.

The project began as an ambitious dream to build a model farm where Hmong families could live, work and retain their cultural heritage. In late 1982, with money from a dozen Hmong families and a resettlement group called Church World Services, a purchase agreement was arranged with a farmer in Homer, MN, near the Wisconsin border. Nearly a dozen families moved to the farm, three hours drive from St. Paul, where they had lived.

In the summer of 1983, Ross Graves, who had helped organize the project, approached the state asking for funds to pay some of the Hmong and American workers. The state came up with the money, but learned later it had not been used to pay the salaries.

The State Attorney General and the Minnesota Department of Human Services began an investigation and the Hiawatha project began to unravel. The Hmong learned the land had not actually been paid for, as they believed. The owner of the farm filed a lawsuit against Church World Services and, in April 1984, the Hmong moved off the land and back to St. Paul.

“There were some very, very difficult months after they moved back,” says Kretzmann. “They had almost no money and we were concerned about their diets, whether they had enough to eat.”

But, the Hiawatha project had some positive fallout. Shoua Vang, who had organized the project, has gone on to use his expertise to organize agricultural economic development projects and has regrouped to form another Hmong farm cooperative in Hugo, MN, 15 minutes away from St. Paul, with funds of their own and support from Church World Services “which wanted to make amends” with the Hmong, according to Kretzmann. “Essentially, they have begun creating what they wanted to create, but the second time around.”

In the back of the meeting hall in Merced one of the three hands drop back down when the moderator asks for those who have full-time jobs to keep their hands raised. Most of the people in the meeting room have been around more than twice. They have all come from other cities and towns where their farming abilities lay fallow, where unemployment was high and land expensive and scarce. Skills as a jungle farmer are not in high demand now, and Hmong are not blind to the U.S. farm crisis that is putting American farmers out of work.

“We just need the know how, the know how,” says one frustrated man.

At Dang Moua’s pig farm the winter rain is still falling. Inside the house, overlooking the barn, his wife and mother-in-law prepare dinner for the children while Dang takes a few minutes to rest. Then he throws on his jacket and heads back to Merced for yet another meeting of the Hmong community. After the children are fed, his wife begins to outline a proposal for a Hmong Women’s project, to promote dual wage-earners in Hmong households. Dang will not be home until late, but in the morning the pigs will be fed, even if he sleeps in. He is learning the American way and, with all the time he spends helping other Hmong in Merced, he says, he made sure his barn was automated.

©1986 Spencer Sherman

Spencer Sherman, a reporter on leave from United Press International, concludes his reporting on the Hmong in America.