FRESNO, California–Making her way through hundreds of Indochinese refugees waiting for English class to begin, Barbara Christl shakes her head as she holds out the morning newspaper. “Here. This is the problem,” she says, heaving the paper on her desk. The day’s front page feature is a ten-years-after look at refugees from the Vietnam War. The headline says, “Indochinese Refugees Adapt Quickly in U.S.” The story opens describing a Vietnamese man in Houston who came to the United States a decade ago with nothing. Today he is on his way to becoming a “Texas tycoon.” The piece quotes a former official of the U.S. Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy as saying Indochinese refugees have “shown a remarkable ability to enter into mainstream American economic life.” Christl, director of English as a Second Language programs for Fresno County, looks like she is ready to scold a child. “You see, people think the problem has gone away. Or if not, that things are moving in that direction.”

Here, the problem has just begun. Since 1979 the counties of California’s Central Valley have become home to 30,000 displaced foot soldiers from the Vietnam War. Fresno County alone is refuge for 15,000 of them. But they are not the soon-to-be tycoon success stories. They are mountain dwellers from the jungle peaks of Laos, primitive tribes, trained by the American Central Intelligence Agency to collect intelligence on North Vietnamese troop movements in Laos, disrupt communist supply lines headed for South Vietnam and rescue downed U.S. flyers shot down just east of their mountain home in North Vietnam. They call themselves the Hmong. To those who knew of their existence during the Vietnam War they are known as the CIA’s “secret army” in Laos.

Before coming to the United States their contact with the outside world had been through CIA operatives and other military men who armed them and directed their forays into the jungle. Before the CIA they had fought for the French when they were the dominant military might in the region. For generations before the war the Hmong (pronounced Mung) stuck closely to their mountain tops, relying on the labor of large families and tightly knit clans to survive on subsistence farming and the export of their only cash crop, opium. The Chinese, who harassed the Hmong out of Southern China near the end of the 1800s, called them Miao–barbarians–and later the Lao called them Meo, a different word with the same meaning.

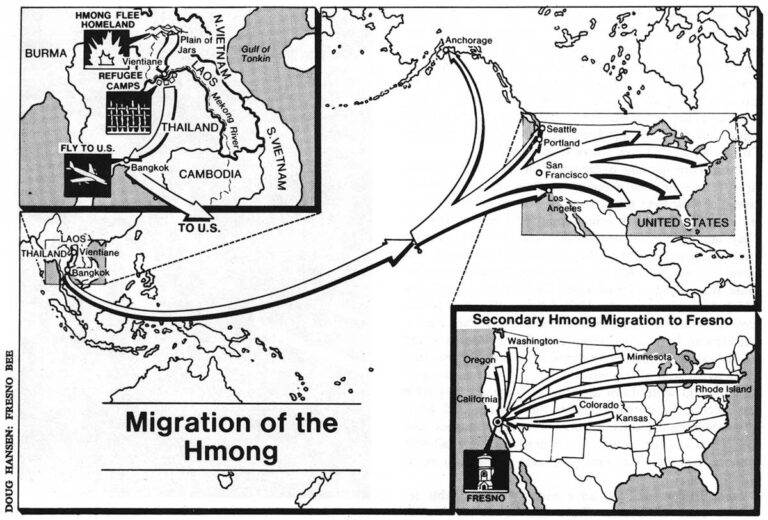

Ten years ago, as North Vietnamese troops took control of Saigon and communist Pathet Lao soldiers prepared to subdue the government of Laos, the Hmong began to stumble out of the jungle and swim the Mekong River to Thailand. They had gained a reputation as fierce fighters attempting to protect their mountain redoubt and their association with the CIA sealed their fate in the eyes of the communist victors. They knew they would not escape the wrath of the Pathet Lao and their benefactors, the North Vietnamese.

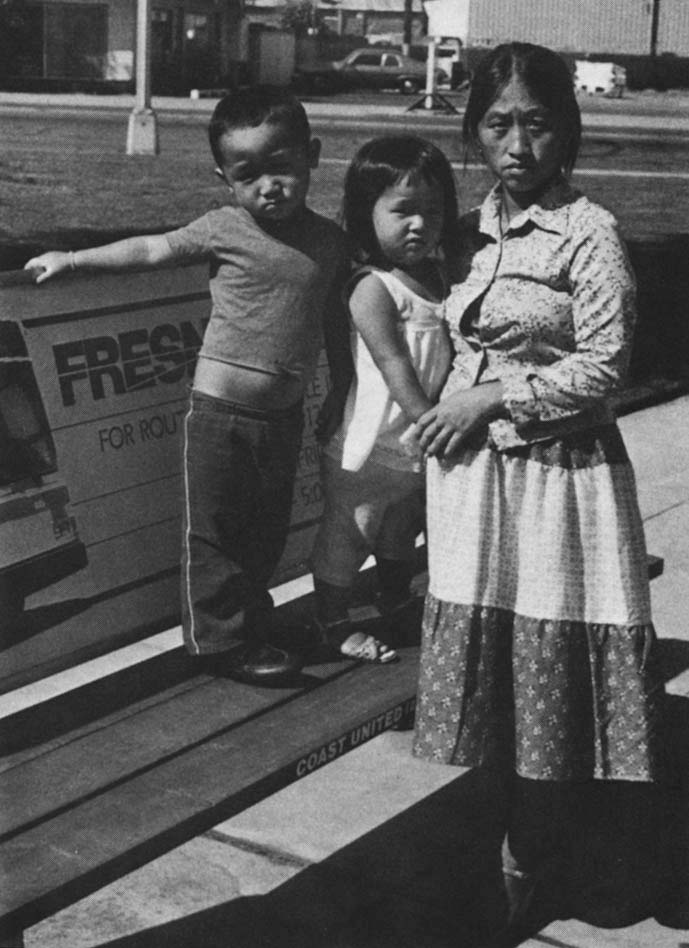

Since 1975, the United States has brought some 700,000 Indochinese refugees into the country. The 65,000 Hmong, like all the refugees, were placed wherever sponsors could be found. Within the space of 72 hours these mountain people were taken from bamboo-thatched huts in refugee camps along the Mekong River and put into 2- and 3-bedroom apartments in Philadelphia, Minneapolis and other major American cities. They were unaware of how to deal with the simplest of tasks for Americans: turning on and off lights; using the refrigerator, stove or oven; paying bills.

“It’s just like a dream, like a movie…Imagine you go to the Moon some way and when you wake up you are on the Moon somewhere and you have to live by that society…you don’t know where you are, you don’t really know,” says Kou Yang, now a social worker in Fresno.

Rev. Norman Johnshoy, who often finds himself explaining the Hmong to perplexed locals, says, “One of the best descriptions is to think of them as a people who made one airplane flight from the 16th century to the 21st. And if you can conceive of something like that happening in a time machine, then you have a pretty good notion of the perplexity that these people must have experienced.”

The cultural disorientation the Hmong face on arrival in the United States is shared by the other Indochinese refugees, but the Hmong bring a special history that makes their long-term settlement much more difficult. Unlike the Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians, the Hmong are a “preliterate” people, which means most are unable to read and write in their own language. Actually, until 30 years ago when Christian missionaries standardized the language and wrote it down, the Hmong had no written language. Unlike European immigrants and many Indochinese, the Hmong have a simple, agrarian vocabulary. Europeans and Vietnamese pick up the English language in months of study, Hmong take years to learn.

“We see (Europeans) in ESL classes as well and they can zip through ESL in no time because you simply substitute what a word means in your language and you learn what that word means in this language. For (the Hmong) there is no word in their language that means the word they’re trying to learn,” Barbara Christl says.

While a very small number of Hmong are educated and have become teachers, businessmen, engineers and farmers, the great majority–estimates run 80 to 95 percent–do not have jobs and do not have skills to work in the United States. When Christl reads that the Vietnamese Texas tycoon “isn’t unique among the 700,000 Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians” in the United States she fears the secret soldiers of Laos will become the hidden refugees in America whose wrenching cultural assimilation will be overshadowed by the success stories of those Indochinese more able to cope. It is a fate the Hmong should not suffer, she says, because of the crucial role they played for the United States in the Vietnam era. Lionel Rosenblatt, refugee coordinator for the United States in Thailand just after the war and again in 1978-81, explains that the Hmong became pivotal for the U.S. military strategy in Laos because “according to the Geneva Accords of 1960 there were no foreign troops to be stationed in Laos.”

“Of course the Vietnamese Army was there in abundance, but the American military did not put ground combat troops into Laos and the Hmong really formed our army–a very unique relationship with the Hmong, therefore, that we didn’t have with any other group on the ground in Indochina.”

Because of that relationship many of the Hmong who arrived in the United States after two decades of war knew nothing else but fighting and nothing else but the support of the U.S. military. Moua Geu, who runs the Long Chien market in Fresno–namesake of the secret CIA operations center in Laos–remembers his relationship with the Americans this way: “They had a lot of powers and they were the ones who brought us guns, gold, clothes, food.”

“CIA is the one who helped us, supported us a lot and we consider them as a mother and father,” he says in a sing-song English, marked by the tonal sounds of his native tongue.

Because of that relationship, the Hmong expected more than they got when they arrived in America. In 1981, during a trip to Ban Vinai refugee camp in northeast Thailand, many refugees responded to the question, “What will you do in the United States?” with the answer, “Whatever the government tells me to do.” It was a great shock to Moua Geu and his comrades when they arrived and the government they had known, that had supported them all their lives, could not be found. “Even if we lost, they promised they would take us to the United States, but when we got here, we have no idea who the CIA is, we don’t know where they went.”

If the Hmong were unprepared for the United States, Americans were also unready for them. In almost every aspect of their lives the Hmong rely on an entirely different set of beliefs and values than their new neighbors. They are a polygamous people. Men have the right to marry as many women as they can afford to support. The more children they had the richer they could become because they could cultivate more land. Hmong men were told before coming to the United States that they would have to divorce all but one wife and on paper they did so. But Hmong leaders in Fresno admit that, once here, the traditional family unit is preserved often with the husband living again with all his wives. Also, while Christian missionaries did write down the Hmong language, they were less successful converting them to the Western God. Most of the Hmong are still animistic, worshipers of good and evil spirits and the spirits of their dead ancestors, all who must be revered with complex rituals and animal sacrifices.

Some benign incidents have been the unavoidable result of these differences. Fresno Police Officer Marvin Reyes swallows hard when he recounts the first time he was invited to a Hmong celebration in a downtown apartment complex. Several women were butchering a live pig in the kitchen. Next to the carcass, beside a blood-soaked wall, the head of the animal stuck out of a bucket, waiting to be cooked as the centerpiece of the meal.

Diana Carter, a clerk at a thrift bakery frequented by the Hmong, said she mistrusted them at first because they would not directly look at her. Later, she learned the Hmong cast their eyes down as a sign of respect.

Another incident was described by Elaine Perez, a Fresno County family planning official. A Hmong couple taught to use condoms through the creative use of a broom handle returned to the birth control clinic after the woman became pregnant. They followed the instructions to the letter, they said. The broom handle had been put in the corner of the bedroom dutifully covered with the birth control device.

Some cultural misunderstandings have led to more solemn consequences. A Hmong man ran a stop sign in a van filled with Hmong workers headed for an onion field outside of town. The van hit a truck and two refugee children in the van were killed. The driver was later arrested and charged with misdemeanor manslaughter, but he was not told about bail and that he could be released from jail if it were posted. Thinking he was in jail for the rest of his life he hanged himself in his cell. “It was a very sad misunderstanding,” said Reyes, of the Fresno police.

Hmong marriage customs have also caused clashes between traditional mating rites and American criminal law. The Hmong practice three forms of marriage; the arrangement, the elopement and the kidnap. The arrangement, made between the parents of the man and woman using go-betweens, and the elopement are the two most common forms of marriage. But the kidnap-marriage is also recognized as legitimate in Hmong culture and involves the male, along with several of his friends, forcibly removing the woman of his desire from her home. After three days together, during which the marriage is consummated, Hmong culture considers the pair coupled. American law considers the man a kidnapper and the woman a victim of rape. Tribal elders have settled many of these disputes when kidnap marriages take place in the United States. But some young women have used the new power they have under American law to press charges. The majority of women acquiesce, however, once the kidnap is over because they are considered unmarriageable by other Hmong men after it has been consummated. In Fresno, the one case that actually went to trial ended in an acquittal. Others have been bargained down to lesser crimes.

In the past, faced with adversity the Hmong have acted as a group and fled to new mountains looking for peace and isolation. In the United States their reaction to their difficult settlement has been no different. Often they have left a city in the night, not even informing their sponsors why they are leaving or where they are going. In Philadelphia the Hmong population dropped from several thousand to less than 250 after several violent attacks on them by their black neighbors in low-cost housing neighborhoods. In Santa Ana, Calif., the population dove from 6,000 or 7,000 to about 2,000 after 1981. Cheu Thao, a community leader there, says many left because of an unprovoked attack on an elder Hmong couple that left the man dead.

“You want to know why the Hmong move from one mountain to the other? Why they always change their place? Then go ask the deer who has been hurt why he defends himself. Ask the deer who changes forests why he changes his place. That is similar to the Hmong,” Kou Yang, the social worker, says.

This flight instinct, coupled with a highly developed word-of-mouth network and the modern convenience of long-distance telephones set the Hmong looking for a new mountain for their people in the United States. For a place they could be together, build a quiet agricultural life and get away from some of the more bizarre aspects of life in America: Big cities, tenements, snow, sleet and hail and the slow dispersion of the Hmong people across the American landscape. That place was Fresno and the surrounding Central Valley. Nearly half the Hmong in the country today have moved to the central valley since late 1979.

But the word-of-mouth did not carry all the news about Fresno that the Hmong needed to know. Agrarian life in Laos means carving out a side of a mountain and planting crops. In Fresno farming is a multi-national concern. Major corporations farm thousand acre plots, advanced technologies are used for planting, fertilizing and picking. “We used to farm for our family to consume,” says Tony Vang, a community leader in Fresno. “In this country you farm to make business. You farm to market, you have to produce good quality to compete with other farmers and I think a lot of people didn’t realize that.”

The dream of farming, while not dead, has been left behind by most Hmong in Fresno while they figure out how to make enough money to rent a small piece of land and make it work economically. Some 200 Hmong farmers have found that specialty crops–like Chinese snow peas and bitter melon–that need more individual attention are one type of crop they can grow and sell.

Even though it was clear early in the Hmong migration to Fresno that farming would not work, they kept coming. Between early 1980 and late 1982, the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement sent 783 refugees to Fresno County, making the total of Indochinese placed there about 1,300. During that time, however, that refugee population rose to 12,500, meaning 94% of the new arrivals were coming from other places in the United States. The vast majority of those arrivals, approaching 100%, were Hmong.

Fresno County, along with surrounding counties, have pressured the federal government into action and word has gone out to Hmong community leaders across the country to try to slow the migration. But county officials are not so concerned anymore about who will come from other parts of the United States. They are looking overseas at the 45,000 Hmong still in refugee camps. Recent reports indicate the Thai government will not allow them to stay there or let them settle elsewhere in Thailand. Many of those refugees have relatives in the Central Valley.

Mouachou Mouanoutoua, a social worker in Santa Ana who has lived in the United States since soon after the end of the war, takes the long view of the problem. He believes that the same beliefs and values that brought the Americans and the Hmong together in Laos will help the Hmong in their adjustment to America.

“Being an American is really espousing the founding principles of America, no matter whether you speak the language or not. And if I say I believe in the founding principles that makes America, I think that is what makes an American. It is your love for it, your belief in it and your labor to protect it. And I think the Hmong probably love and know in their hearts that these principles are what they have fought for, even in Laos. To live by the basic principles of freedom.”

That makes sense, he says, because in their language Hmong means Free Men.

©1985 Spencer Sherman

Spencer Sherman, a reporter on leave from United Press International, is reporting on the Hmong in America.