It didn’t unravel all at once. In Santa Ana, south of Los Angeles, some say the resettlement of the Hmong began to come apart in 1981 with the robbery and murder of an elderly refugee. Others say it began when leaders of the former CIA “secret army” in Laos called for their troops to gather in one place and prepare for a return to the homeland, high in the mountains of Indochina overlooking North Vietnam.

In other parts of Southern California it began to come apart a little earlier, in late 1979. The number of Hmong families at first dwindled and for no clear reason. Then, like a torrent, they moved out of Los Angeles and its surrounding suburbs.

In Philadelphia the pressure built over several years as blacks in the city’s ghettos attacked the newcomers from Southeast Asia. The soldiers and families of the secret army were competing for housing, jobs and welfare dollars. The tension led to sidewalk attacks on refugee men. A window was shot out of a Hmong house and threats of violence were common.

In Portland and Seattle it came undone when the federal government changed a welfare regulation cutting benefits to refugees in many states, including Oregon and Washington. It began slowly, but by late 1981 whole groups of the refugees were disappearing from their new homes and the government’s resettlement of the Hmong went into a tailspin.

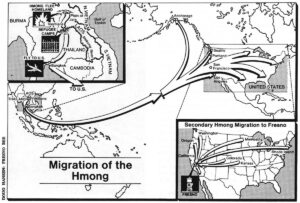

Half of the 65,000 Hmong refugees settled in this country since 1975 packed up and moved. Nearly 30,000 of them came together in California’s San Joaquin Valley during a migration unprecedented in the resettlement of nearly 800,000 refugees from the Vietnam War.

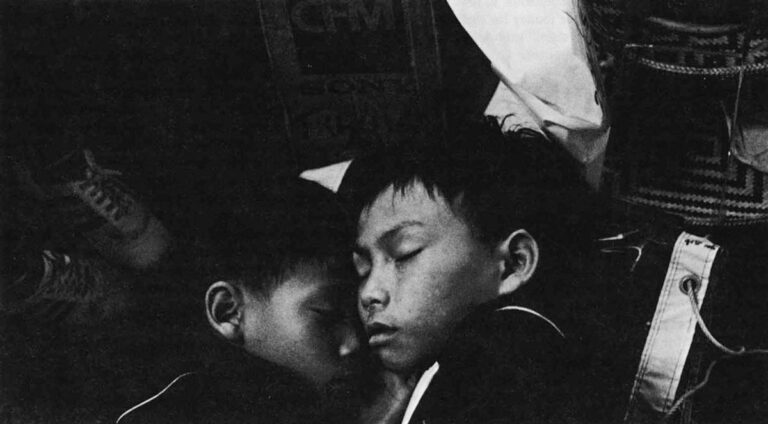

The Hmong felt terrorized by America’s inner cities and frustrated by an unwitting U.S. refugee policy that split up their traditional tribal groups, leaving small settlements floating rootless and exposed in tough urban ghettos.

The seemingly spontaneous movement to the San Joaquin or Central Valley, as it is also known, has federal resettlement officials befuddled and local politicians angered. Federal officials are still wondering what went wrong and local officials are deeply concerned over who will pay for resettling the Hmong a second time. Some bitter animosities have sprouted between politicians in Washington and the Valley.

What is unusual about the migration is that it is one of only a few flaws in an overwhelmingly successful program: the rescue of 1.5 million refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos and their resettlement in the West, primarily France, the United States, Canada and Australia. The United States has taken nearly 800,000 Southeast Asians since 1975 when Indochina came under communist rule. More wait in Thailand hoping for their turn to come. Roger Winter, director of the U.S. Committee on Refugees, a private lobbying group, calls the resettlement of so many people, “the largest international humanitarian effort in history.”

In that context, the story of the Hmong seems a small problem. For two reasons it is not. The 30,000 Hmong in the San Joaquin Valley have strained local resources. County officials turned to Washington for financial support, but feel their pleas for help are answered with halfhearted efforts. A schism is developing over the moral and fiscal responsibility for teaching the thousands of unsophisticated Lao highlanders how to read and write and find a job.

The migration highlights a problem that will not disappear in the coming years as refugee groups from other countries seek asylum here: what burdens are local governments expected to assume when policy decisions made in Washington result in large refugee populations settling in their towns and cities?

Fresno County Supervisor Judy Andiron, whose county of 500,000 people is now home to 15,000 Hmong, recently outlined the problem this way:

“To leave this community to deal with the problem (of resettling the Hmong) on its own I think is a very unfair position for the federal government to take. They did bring these people into the country and they did make promises to them and the local governments are simply not going to be able to keep all those promises.”

Secondly, the uncoordinated flight of the Hmong to the San Joaquin Valley has led to questions about the way refugees are settled in the United States. Successive groups of European refugees and immigrants have been dispersed across the nation to lessen their impact on any one community; none of them has faced the turmoil of the Hmong. The clannish Asian mountain tribesmen did not take well to being split up. Their flight to California showed refugee officials did not understand the structure of Hmong life in Laos or the impact of inner city living on primitive Southeast Asian highlanders.

The Hmong lived in tightly knit groups in the hills of Laos. They were organized by the French to fight the growing communist movements in Vietnam and Laos in the 1950s. When the United States stepped in to replace the French as the dominant military might in the region, the Hmong were recruited secretly by the CIA to fight communists and Vietnamese soldiers. What developed between the Hmong and their covert advisers in which the Hmong actually served as the U.S. presence in the area.

When the Hmong were not fighting, they farmed on isolated slopes, growing rice and vegetables along with their only export crop, opium. They kept their distance from the Laotians living in the lowlands and had little contact with the modern West, except through military advisers and weaponry.

The Hmong lived a highly organized, regimented existence, which was one reason they made good soldiers. But it is also the reason why they did not adjust to being split up and settled wherever sponsors were found for them in the United States. Other cultural differences made their adjustment difficult. In order to be accepted into the United States they had to renounce polygamy, a traditional practice. They also had no written language until 30 years ago when missionaries wrote it down, so most are illiterate in Hmong and English.

Since the early 1960s, the Hmong were supported with food and military aid from the United States. When the war in Laos heated up through the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Hmong became refugees in their own land as the civilian population followed the soldiers forward into their mountain villages during victory and backwards into the lowlands in defeat. With their agrarian life disrupted by the cycles of war the Hmong became dependent on deliveries of aid from U.S. supply planes. It is not strange then, that the Hmong arrived in the United States after the war as people dependent on outside aid.

But when the Hmong began to come to this country in 1975 their separate needs were not considered. Phillip Hawkes, director of the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement, said officials “didn’t have time to look at the country and say what would be the best place to put the Southeast Asians as opposed to freedom fighters from Czechoslovakia. They sent these people to where the structures were in place. So they wound up in downtown Philadelphia, Providence, RI, and downtown Chicago.

It is easy to see why finely tuned resettlement plans and specifically tailored programs for different Asian groups were not developed. There were just too many refugees arriving in too short a time. In the eight months after April 1975 the United States accepted 130,000 refugees from Indochina. They were mostly educated Vietnamese military men and their families and others who had worked directly for the U.S. government. But then the flood seemed to stop and, as Alicia Cooper of the International Rescue Committee in Orange County, CA, remembers, “we closed up Camp Pendleton on October 30, 1975, and went home and on to other things.”

It appeared to refugee workers that the system had worked. More than 100,000 refugees had been spread across the country and the crisis was over, they thought. But, as history shows, the crisis was really just beginning to build and in 1979 refugee resettlement agencies would be overwhelmed by the “boat people” from Vietnam and the “land people” fleeing by the thousands from Cambodia and Laos.

Between 1976 and 1979, 64,000 Indochinese refugees were admitted into the United States. During 1980 President Carter raised the authorized number of entrants from 7,000 to 14,000 per month. That year 180,000 Indochinese were brought to the United States and each successive year saw hundreds of thousands more admitted. At the same time 125,000 Cubans were given asylum and 20,000 Haitians landed on the beaches of South Florida.

In April 1980 Roger Winter was appointed to become the first director of the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement. It was a tumultuous time, he recalls, and he was not aware that different groups of arriving refugees might have different resettlement needs.

“I must tell you that when I first went to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, I wouldn’t have known what a Hmong was,” he said recently in Washington.

It was at the same time in 1980 that Hmong leaders realized they could no longer wait for the U.S. government to come up with proposals to solve the problems of their people. “We realized we would have to act, do what we thought was to have been done for us,” remembers Cheu Thao, a community leader in Orange County, Calif. Several Hmong leaders revived an idea that had simmered in the community since early in their diaspora: find a place where Hmong could live together and recreate, in part, their former existence in the hills of Laos.

Phillip Hawkes, the Reagan administration’s resettlement chief who replaced Roger Winter in 1981, remembers being approached with the idea of the federal government buying some land for the Hmong to farm as an alternative to welfare.

While he believes the Hmong had a good idea which would reduce the cost of welfare aid to the refugees, he said it would never work.

“Can you imagine some Vietnam Vet who has his ranch foreclosed in Fresno, only to see 200…Hmong tribesmen move onto it at government expense and set up farming? You’d have a war!”

While the debate over resettling the Hmong continued into 1981, disappointment and despair were building in Hmong communities around the nation. In Oregon and Washington, Hmong began to talk about a federal welfare regulation that would take effect in early 1982. In some states, benefits for housing, food, clothing and education would be cut off to refugees who had lived in the country more than 18 months. In other states, like California, with more liberal welfare benefits, refugees would be supported for 18 more months. Before the regulation took effect 37 percent of the Hmong in Washington and 94 percent of the Hmong in Oregon moved to California.

A few Hmong had moved to the San Joaquin Valley in late 1979 and seemed to be surviving through farming. A few more Hmong leaders moved there and soon the Valley was looking far better than the harsh realities of Philadelphia, Seattle, Orange County and L.A. By 1982, the big move was on.

It was only then that officials began to rouse themselves to look at the problem. Local welfare workers saw it first and turned to their superiors asking where the money was for the increased caseload. County officials, in turn, called Washington with the same questions. But by that time the massive migration of the Hmong to the valley had already outpaced the government’s ability to respond.

From the top floor of the Merced County Building Supervisor Ann Klinger can see B-52 bombers bobbing and weaving their way across the wide San Joaquin Valley, maneuvering towards practice landings at Castle Air Force Base. The valley is a natural place to test land the green military giants; it is almost surveyor perfect in its flatness, drawn into green and brown rectangles of cotton and row crops, alfalfa and corn. From her window it is easy for Klinger to be reminded of her constituency: farmers and soldiers, migrants and locals who work in the fields and benefit from the infusion of Defense Department dollars which help smooth over rough financial times brought on by the vagaries of a farm economy.

By 1982 Ann Klinger and other Merced officials knew they had a problem. Thousands of Hmong were descending on the sleepy county of 157,000 in California’s agricultural heartland. And while Klinger is supportive of minorities and immigrants, she also quickly saw the Hmong as an economic problem. She remembers first the impact on the schools.

“A classroom a week of Hmong students enrolled until in a short time there were enough refugee students to fill a school larger than the largest school in the Merced City Elementary School District,” she said.

But government aid for the refugees was still being sent to other areas where the Hmong had originally been settled.

“Some other school district in another part of the United States receives some money to help educate the refugee students, but they don’t have the students anymore, we do,” she said.

Klinger was stunned by the federal government’s response to her questions about funds for the refugees. “They just about said it was our problem,” she said.

In Fresno County, 50 miles south of Merced as the crop-duster flies, local welfare official Robert Whittaker expresses similar dismay at the federal response to the Hmong influx. The process of convincing the federal government to come to the aid of his county “took about a year,” he said.

“As a matter of fact, in 1983 when the first targeted assistance program was passed by Congress to help impacted counties, Fresno County was not even listed as an impacted county. Even though we had 8,000 refugees,” he said.

Whittaker’s office estimates that in 1980 there were fewer than 600 refugees living in Fresno, all of them Vietnamese. By 1983 there were 8,000 refugees in the county; in 1984 there were 10,000; and by 1985 the number was nearing 15,000, nearly all of them were Hmong. No Hmong were officially resettled in Merced County, but by February 1985 there were 7,000 living there.

The federal government pays 100 percent of the resettlement costs in California for refugees during their first 36 months in the country. But that does not console either Ann Klinger or Robert Whittaker. Since most of the Hmong in the Valley have come from other places in the United States, they are closing in on or have passed the 36 month date when the county will have to start paying a portion of their support. While the county contribution for welfare is usually only 5 percent, local officials think that is a big chunk of their budget, which has been reduced over the past few years by the California-spawned “tax revolt.”

What bothers local officials is that nine out of 10 Hmong of working age do not have jobs. They are still attempting to learn English and vocational skills. Even if they had skills to work, jobs are at a premium in the Valley where unemployment hovers at 18 percent.

Fresno is a city of immigrants, from the children of dust bowl Oakies to the large Armenian population whose favorite son was the writer William Saroyan. It is also a city of migrants, Hispanics and blacks who move in with the ripening crops and on when the picking is done. It is not the kind of place that routinely shuns newcomers. But there is an undercurrent of anger now. It is not focused directly at the Hmong, but at the Washington bureaucracy that failed to warn of the impending refugee influx and responded sluggishly to cries for help.

Many officials in the Valley believe H. Eugene Douglas, ambassador-at-large for Refugee Affairs at the State Department, and Phillip Hawkes, are not sensitive to the problem of how long it will take to absorb 15,000 new-comers. To prove their point they cite proposals from Reagan administration budget cutters to end subsidies to the counties that pay for special refugee training.

Robert Whittaker calls their policies “haphazard and cavalier;” Supervisor Klinger, a blunt woman when she is angry, spoke of the men in unprintable words; Judy Andreen, more politic, said they did not “understand” the local problems.

Klinger likes to explain the problem in personal terms. She tells of a Hmong man who once told her that all he knew was “how to kill people. That’s all I did in my country. When I was 10 years old I had a gun in my hand and was fighting for the CIA,” she recalls.

“That individual had never been given the opportunity to learn a skill that was marketable in the San Joaquin Valley,” Klinger said, “yet Ambassador Douglas and officials in Washington, tell us that somehow we are to blame if we don’t push a button and that person somehow acquires skills.”

Local officials think the best solution is to keep the federal tap flowing until the Hmong learn skills and are absorbed into the local economy.

But more than anything else, Fresno Supervisor Andreen says time must be given a chance to solve the problem.

“We could mobilize every resource available in the county and probably in the state and still, you are dealing with peoples’ lives and you cannot just change those people, they become assimilated over time.

“I think there are things we can do to make it worse and hopefully there are things we can do to make it better, but there is no way we can solve it,” she said.

“Hell, if I knew a solution, if it wasn’t outrageous in cost, I’d pursue it if it wasn’t outrageous in cost. But I don’t know any solution.”

That was Phillip Hawkes, head of refugee resettlement programs for the federal government, letting off steam in Washington last May. A soft-spoken California anthropologist, he quickly admits that he does not understand what the Hmong want or need to make their resettlement successful. He believes it is unhealthy for so many Hmong to be living in the Central Valley because there are few jobs and limited motivation to learn English if they are surrounded entirely by Hmong. His belief is bolstered by the high rate of unemployment and sluggish adaptation to life in the Valley, especially among the older refugees.

The solution he is pursuing at the Office of Refugee Resettlement is to urge as many Hmong as possible to move out of the San Joaquin Valley and live in smaller communities where employment opportunities are greater. He also wants to stop the flow of Hmong to California and he has tried that in several ways.

In 1984 he tried to persuade Hmong who were just about to emigrate from refugee camps in Thailand to settle outside the San Joaquin Valley. But refugee workers in the field thought the plan was a waste of time and doomed to fail.

“They would just come to California a few months after they arrived anyway and the money for their support would still be going to another state,” said Alicia Cooper of the International Rescue Committee.

That Hawkes proposal failed.

His newest proposal is called “planned secondary migration,” In an attempt to get Hmong families to move to areas outside the Valley he is offering the resources of the federal government to move them, if they volunteer. Again, he is unsure he has support for the idea from the Hmong leadership, or even whether he is talking to the right leaders.

“I talk to the young ones, English speakers, but I’m not really sure if they are the leaders that make these kinds of decisions. In fact, I’m sure it is the old leaders, the clan and military leaders, who make these decisions, but they aren’t the ones I can talk to,” he said.

But, he said, “even if one or two families move away from Fresno and get off welfare it will have been worth the effort and the money,” he said.

Hmong resettlement, he points out, does have bright spots. Several communities are faring well, especially in places where housing is cheap and unemployment low; places like Providence, RI and Morgantown, NC are held out as good examples of Hmong successes by Hawkes.

Hmong also share some similarities with other Asian immigrant groups that are thriving in the United States. Like Japanese, Koreans and Chinese, who are stepping quickly into the U.S. economic fast-track, the Hmong have strong family ties and traditions of domestic stability.

Many Hmong parents are pushing hard for their children to become educated, although young women who traditionally marry in their early teens are dropping out of high school at high rates.

Hmong who run businesses involve their entire family and groups of refugees are combining their funds to start lending money to other refugees. Hmong have also learned the importance of self-help groups, and they are organized in every Hmong community in the country to provide language and vocational training and lessons on American cultural life. Most importantly the self-help groups–called Mutual Assistance Associations–are places Hmong can teach other Hmong from their own experiences and mistakes.

Hmong leaders have to give their people some stake in their current communities to prevent future migrations, which would only prolong their dependence on welfare. A massive move to a new community with jobs for only a few would just move the problem to a new place.

These small steps are being taken to counteract large problems created by lack of planning for the Hmong and their special needs. But like U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War itself, the resettlement of the Hmong has been an experience where reality confounds theory. Too many refugees arrived in a relatively short period of time and old resettlement policies would not work for the Asian tribal newcomers.

Nearly all federal and county officials interviewed for this story agreed the welfare system should not be used to support the Hmong. Welfare dependency began for the Hmong in Laos when the CIA supplied all their needs. The welfare system continues to support the Hmong in the United States and does not provide any incentive for them to adapt to their new surroundings. Roger Winter says he tried to revise the system when he was in the government to get Hmong out of the welfare department, but his suggestions were never implemented.

But most disheartening for the Hmong has been the loss of trust they had for their American allies, and its replacement with the frustration and despair they feel towards their resettlement in the United States.

“We are like a soccer ball. One agency gets to kick us for a while. Then another agency gets to kick the ball. What happens in the end is every service provider has kicked the ball and the Hmong have gained nothing,” said Santa Ana, Calif., community leader Cheu Thao.

But, those feelings have not dampened the desire of Hmong leaders to keep the immigration doors open for their people still living in refugee camps in Thailand.

Just how important refuge in the United States is to the Hmong and those who work with them was highlighted last March after Ambassador Douglas proposed in a letter to Paul Harding, UN High Commissioner on Refugees, to move Hmong in Thailand to China instead of the United States.

After details of the plan leaked to refugee groups, the White House was forced to disown it, saying it was not U.S. policy to close the doors to refugees still waiting to come to the United States.

Recently three Republican and six Democratic senators have called for Douglas to resign because of his attempts to frustrate U.S. refugee policy. In one incident they said Douglas went to Thailand and “undermined Thai confidence as to the United States’ resolve to protect or resettle Indochinese refugees.”

The sharp backlash indicates that more Hmong will be coming from Thailand. And that only heightens the need for innovative and coherent plans for their resettlement, plans that need to be made before the new Hmong arrive and begin to seek out their relatives in the San Joaquin Valley.

©1985 Spencer Sherman

Spencer Sherman, a reporter on leave from United Press International, is reporting on the Hmong in America.