MARION, North Carolina–Eloise Witte first heard about the Laotian refugees coming into the county when she read it in the McDowell News. Then she started seeing them peering into shops on Main Street and buying pants and shirts at Belk’s. Most of the women were “pregnant out to here,” she says with a smirk, and they were carrying six or seven more babies in their hands, in carts, in slings, in just about everything but strollers. When 25-pound bags of rice began appearing in the grocery store in the fall of 1980 and Mike Gibson at the Social Services department asked for some tax money to hire a refugee worker, Mrs. Witte could see the specter of change coming to McDowell County, and she was none too pleased.

Then she heard several local churches were responsible for bringing the Asians into the county, and she “just got riled up.” If it was the churches bringing them in, it better be the churches paying their way, she thought. She guessed the deacons would be “walking straight to the welfare office” with the refugees, and she figured that gave her the right to put in her two cents. So she picked up a pen and wrote the McDowell News.

“Now that these churches have decided to play stork for the county, I hope they will not only pay for the keep of these Laotians, but do something about their birth rate. They have just about bred themselves out of a place at the world’s table. If we fall heir to another 100 to 400 families, 15 years from now we will probably be called Laos, NC,” she wrote. Others followed.

Mrs. Witte became part of an impromptu ladies’ platoon of letter writers, sounding the alarm against what she called “these breeders par excellence” being shepherded into rural McDowell County by the Garden Creek Baptist Church, one of dozens of simple steepled red-brick sanctuaries that poke out of the wooded foothills and valleys of the Blue Ridge Mountains of western North Carolina.

“It’s that ‘Y’all come down’ thing I was against,” Jane Greenlee, a former county commissioner, says of the traditional Southern hospitality and Christian charity that she thought was getting out of hand with the refugees.

Her reaction “was not a racist or bigoted thing, it. was hard sense,” she says. “Sometimes business is business.”

But what has happened in McDowell County and nearby Burke County over the past five years could never have been predicted from that first blustery response to the arrival of the refugees. The pastoral foothills of western North Carolina have come to be among the few places they have been able to find some peace after the destruction of their life in Laos.

It was a little rocky at first, as locals began to see Asian faces and costumes on the streets. Rumors and questions filled luncheonettes, the aisles at Belk’s department store, church meetings and the News. Why weren’t they left in Southeast Asia at the end of the war, they asked. How do we know these Asians didn’t kill our boys in Vietnam? Who’s going to support them? Why don’t they have to pay taxes for seven years?

Rumors like those got some people angry. “We had people calling the church office and threatening to burn the parsonage and said they were going to march around the parsonage and they were going to march around my trailer, and I should not be surprised if it burned,” said Don Guffey, the assistant pastor at Garden Creek in 1980.

In the verbal feud that continued through the fall, the citizens of McDowell County and the 3,500 residents of Marion, its largest city, learned more about these new arrivals than they probably knew about their neighbors. The Asians weren’t actually Laotians at all, the locals found out. They were Hmong, members of a hill tribe that had lived in the mountains of Laos and North Vietnam and fought for the United States in a secret operation mounted against Vietnam during the war.

Feelings became complicated when church leaders revealed the Hmong war record: the Hmong had been recruited by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency; per capita, 100 times more Hmong soldiers than Americans had died fighting; the Hmong got no recognition for their sacrifices because their battles were cloaked in the secrecy of a CIA covert operation.

Nor were the new arrivals going to cost the county money, their supporters insisted. “In fact we really make money on them,” says Gibson of the Social Services Department, because the federal government pays for all resettlement services provided for the Hmong and kicks in administrative costs as well that are used in other programs.

So it was difficult for the ladies’ platoon to rouse any support against these unassuming Asians, strange-talking allies. To speak out too loudly against them, a lot of townspeople felt, was unchristian and intemperate. And it is hard to buck the tide of Christian charity when it gets rolling in a county of 35,000 people and 155 churches; where sales of beer and hard liquor were banned until 1984-and then only squeaked through by 28 votes; where gasoline stations post signs exhorting customers to “seek ye out the book of the Lord and read” next to ones announcing “Visa and Master Card accepted here.”

Stories about their difficulties made the rounds at covered dish church socials and down at the Sizzler “flamekist” Steakhouse where the local politicians eat. Rev. Allen McKinney, pastor of the Garden Creek Baptist Church, worked just up the hill from the steak house, and he eats there nearly every day with his neighbors and friends. McKinney, who became a driving force in the resettlement of Hmong in McDowell County, dispelled many rumors over lunch, convincing the locals of the proposition–odd at first–that the Hmong and McDowell Countians really had a lot in common.

The Hmong didn’t adapt well to the fast-paced life in urban areas where they were first settled; places like Philadelphia, Detroit, and other cold northern cities. Residents of McDowell County avoid such places, too. What the refugees wanted was a plot of land, a house, a garden, and a job, just like the locals. Here, good fences make good neighbors, and the Hmong share that belief. They might not all be Christian–though some are–but they seemed God-fearing, even if their savior wasn’t precisely the Lord Jesus Christ.

While it is still a tenuous experiment, two former officers in the Hmong secret army are attempting to slowly draw a group of their people away from unemployment and stagnation in the nation’s urban areas to North Carolina and a place where they can recreate the simple agrarian life they lost a decade ago. They hope to serve as a model of agricultural success, full employment, house ownership, and mental health elusive to many of the 65,000 soldiers of the lost secret war. Many of them have spent the decade since leaving refugee camps in Thailand drifting around the U.S. looking for a place of their own.

The idea of helping the Hmong started at Our Lady of the Angels, the only Catholic Church in Marion, which brought a family to the area in 1976. Nobody said a word then because the resettlement was done quietly.

After they had sponsored a second family, the Catholics turned to the Methodists to spread the burden of charity, and the wealthy First Methodist Church agreed to take on a Hmong family. With all the television coverage about the tragic plight of the refugees from Asia, they felt it would be a Christian thing to do.

At the same time, Allen McKinney of Garden Creek Baptist was watching television. “One day I was sitting in my chair watching the news and I was weeping over the plight of those people and something just said to me, ‘why curse the darkness, better to light one match, you know.’ ” McKinney stirred up the consciousness of his congregation the next Sunday, and they agreed to sponsor a Hmong family from the Catholic Social Services agency in Charlotte, 90 miles to the southeast.

McKinney presented to his congregation a plan to sponsor a family of four. A barrel-chested Baptist with a 6 1/2 foot frame and a manner that glides easily between friendly neighbor and stern preacher, he arranged with a member of his congregation for a house trailer. Others chipped in with kitchen supplies, towels, sheets, and clothing. But on the day of their arrival in Charlotte, McKinney was in bed with the flu, so he called Don Guffey, the associate pastor. Guffey agreed to drive down to the airport and pick them up.

Guffey didn’t know it at the time, but what he found at the airport was a small hint of what was to come.

“Well, when I got there, there were seven of them,” he says. “They had brought along a mother and a father and sister. So I drove them on up to Marion, and that’s how it all began.”

Comparing notes over the telephone, the new residents of Marion, direct from refugee camps in Thailand, began convincing relatives in other areas of the United States to become part of the North Carolina experiment.

“So they began to ask whether others could come and live here. I said why not. It’s a great place to live and they was having such a difficult time elsewhere,” Don Guffey recalls.

At first the newcomers brought in other members of their own clan, one of 20 that the Hmong divide themselves into. Each clan is large and, traditionally, members enjoy living in the same area for social, political and economic reasons. In Laos, the more members of a clan that lived in one area, the more power they had, more food they could grow and the richer they became.

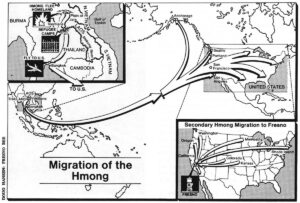

But every Hmong sharing the same clan name is related–they call each other cousin–and by their laws cannot marry. So soon after one clan moves to an area, they become interested in attracting other clans to make sure that their children have enough of a selection for marriage. This pattern of social migration is not new. It has been practiced for centuries as the nomadic Hmong moved from Southern China into the mountains of Laos and North Vietnam, pushed by ethnic animosities until they found a mountain redoubt between the lowland Laotians and the Vietnamese.

The Vietnam War disrupted these social patterns, literally making the Hmong a tribe of refugees in their own land. At the peak of the war, nearly the entire population of Hmong were soldiers or refugees moving into the hills for battle, back to the lowlands in retreat.

Once settled in the U.S., the instinct to regather the clans began to influence the Hmong again, this time with a special urgency. The U.S., they had found, presented a situation of outward peace, but the strangeness of the modern world confused many of the less-educated Hmong who yearned for the old patterns of their lives.

Motivated by the desire to regroup, many Hmong moved to California in the early 1980s to be close to their former military leaders, incorrectly believing that they might be able to farm there. Largely unemployed and living in large groups, bolstered by California’s generous welfare policies, many of the 30,000 Hmong in the San Joaquin Valley felt little need to learn English or assimilate.

To some of their leaders, assimilation appears undesirable. Harboring hopes of building strength for an eventual return to Laos, the leaders encourage the Hmong to stick to the existing community. In the meantime, many believe, the generous welfare benefits are an appropriate reward for long, difficult service to the United States.

Those who moved to North Carolina saw things differently. While many of the McDowell County locals saw what they thought were welfare-dependent families moving to the area, for the Hmong, the decision to move to North Carolina was, in fact, made only after considerable thought and planning. North Carolina has virtually no public welfare for refugees. At a minimum-wage job in Marion, a worker can make $536 a month before taxes and health insurance. In California, many Hmong families are given $1,000 per month in aid. While Hmong from North Carolina have moved to California and other high-welfare states, those who have stayed are not on welfare. In McDowell County in August, 1985, one family was receiving aid and two others–a family with eight children and a widow–were getting food stamps.

The move to McDowell County was also political. In 1980, shortly after Garden Creek Baptist brought its first Hmong families to Marion, a Hmong leader chose McDowell County as his refuge. Many of his followers began moving to the area.

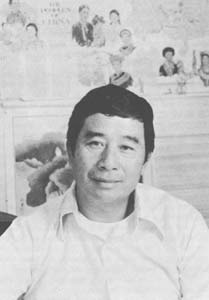

Captain Kue Chaw had been one of a band of Hmong soldiers loyal to the French who in 1954 rushed to Dien Bien Phu in an unsuccessful attempt to help save the garrison there from communist attack. After that loss ended French influence in Indochina, the Hmong joined forces with the U.S. and Kue Chaw retreated to northern Laos to organize anticommunist Hmong. Eventually he served as a liaison officer at the secret Hmong military base at Long Chien, Laos. He escaped with his family to Thailand in 1975, just as the communist victors began lobbing mortar shells onto the airstrip.

In 1980, he toured the U.S., looking for a place to move his family. Philadelphia, where they had been settled, was too foreign to him, too different from the hills of Laos where he was born and had fought all his life. There were few trees, no land for gardens. The lakes and streams were dirty.

“We first came to Philadelphia in 1976. We first saw snow. It was near the end of the season. We wondered, ‘what is going on here?’ We were surprised. We did not know how to handle the situation at the time,” he now recalls.

“So I went to Ohio, Detroit, Minnesota and Los Angeles, San Francisco, Santa Ana, Memphis, West Virginia, Virginia, Washington, Richmond. I thought Georgia was the place I was planning to come. But I went down there, but it looked very crowded too. So I come up here and thought it would be the best place for me,” he says.

McDowell County looked nearly perfect for this longtime secret soldier. It was rural, wooded–it looked like the hills of Laos, filled with lakes and streams and plenty of inexpensive land. For Kue Chaw that was enough, and his approval was enough for his followers. By the time the ladies’ writing platoon took up pens in the fall of 1980, nearly 500 Hmong were living in McDowell and Burke Counties.

Kue Chaw and his friend and former military ally Ma Lo set the tone for the Hmong now in McDowell County. The Hmong generally stay out of sight downtown, but on rural Dysartsville Road, 15 miles south of Marion, they have bought houses and gardens and nearly everyone is working in a textile mill or furniture factory or at the Baxter-Travenol pharmaceutical plant.

Kue Chaw has planted a rice paddy to see if rice from the Laotian hills will grow in the Blue Ridge. He is waiting for a package from his sister in Laos with seeds of the trees and shrubs of his native land so that he may see the flowers of Laos blooming in North Carolina. Over his desk at the Hmong Natural Association, the community’s self-help group, he has pinned his philosophy on the wall: “You now are in the land of opportunity.”

He says the dream of organizing to return to Laos needs to be rejected in favor of planning a future for his family and people. He is bitter about other Hmong leaders who, he says, are taking advantage of their unhappy followers by holding out the possibility of a return. All that does, he says, is prevent them from making a decision to make their lives in the U.S.

“I will not be involved with the dreams of angry men,” he said recently. “We have lost one generation. We cannot wait until the third generation. It is the children now who must get education. As a minority, we must work harder, study harder, be the best and more,” he said.

“If you come to Marion, you must work. This is what life in America is about,” he says.

The belief that the Hmong are getting a free ride, however, still persists. Sitting over the remains of a steak recently, County Commissioner Ron Byrd wondered whether it was true the Hmong did not have to pay taxes. Pastor McKinney, sitting across the table using his deep Sunday morning sermon voice, set him straight.

“You know everybody has to pay taxes, no matter who they are, Ron,” he said. The commissioner shrugged and went on to talk about high school basketball.

Even Eloise Witte’s anger has been softened because the Hmong keep such a low profile in town. But she is still galled at the way Allen McKinney and the Garden Creek Baptists went about bringing the refugees to the Blue Ridge.

“What that minister had in mind was to bring them in here and then let everybody else take care of them. And then he’ll stand up there and say, ‘See what we did for these nice people.’ Well Baloney!” But those few discordant voices are now only echoes of the commotion five years ago.

On Labor Day weekend, 1985, the Kue clan met to plot the future. From Merced, Calif., and Portland, Ore., came Kue Chaw’s brothers. He had not seen them since Long Chien, a decade ago. From the next generation in Portland came Kue Sou, a social worker, and his cousin Kuxieng, a shop owner whose first name is crossed out on his business card and replaced in pen with the name Donald. He had just become a citizen.

They came to look at North Carolina, feel the air, touch the chicken coops and view the sweep of the horizon from Kue Chaw’s farm. Did it really look like Laos, as people have said?

Men sat at the Friday night dinner table, women served the dishes, and the children ate standing up around the table. Kue Chaw noted the fish he has caught in a nearby lake, served smothered in hot peppers. Over a piece of white bass, Kue Chaw outlined the evening.

“We will stay up until midnight tonight setting the agenda. We must have an agenda. Then we will gather again tomorrow morning for all day. I choose the first subject on the agenda. Poverty. How we will raise our people out of poverty. Then we will discuss the future of my family.”

As the men left the table, women and children took their places, dipping large spoons into tureens of chicken soup and bean curd, spicy meat and bitter melon, pickled vegetables and mounds of white rice.

At the sink, Kue Chaw’s 14-year-old daughter washed the dishes, dressed in black pants and a shiny black blouse with fashionable twister beads of red, pink and silver around her neck. In a picture on the wall she is adorned in traditional garb, a black turban, ornate silver necklace and multi-colored skirt of a thousand pleats. She does not like school, she says, because it makes her miss the soap operas on TV.

Over the fireplace hung a watercolor picture of Jesus Christ. Over the kitchen table, a tan paper dotted with sprouts of blackened chicken feathers sat, a gift from a local Hmong shaman to bring prosperity into the household and make its members thrifty.

“One day, when we are more visible, it might be a problem. Because we young are ambitious. We will make it and maybe then we rub a few feathers the wrong way,” said Kue Chang, Kue Chaw’s second son, as he sits under an Oak tree on his father’s land dressed in Adidas and jeans. He studies computer science.

On Labor Day evening, fireflies in the dusk outside the screen door shoot off incandescent flashes in the trees; fog slips up the valley to the top of the forested hills, and some signs of permanence are here for the Hmong. Kue Chaw’s rice paddy is just over the next rise, chickens run on Dysartsville Road, Hmong youngsters play hide-and-seek with their North Carolina neighbors. They are not too worried for now about being accepted here; live and let live is the order of the day.

But, for Kue Chaw, permanence must first be a state of mind for his people. Like in the past, they must bond themselves to some place and call it their own.

There is no sense of urgency in the scene, only in the eyes of Kue Chaw who settled down into a chair, looked at his family around him and paused, waiting for the appropriate moment to place the idea in his brothers and cousins that the hills of the Carolinas might well be the place for them to turn peace into prosperity.

©1986 Spencer Sherman

Spencer Sherman, a reporter on leave from United Press International, is reporting on the Hmong in America.