(SANTA FE, N.M.) – In the spring the rain ran in scarlet streams down from the hill where the pool was, rutting our ball courts and the rose gardens, staining the cinder-block foundation of our old wooden dormitory. We skipped crazily from building to building in those March and April monsoons. Sometimes it almost seemed as though we had moved outdoors. But we knew then home and summer weren’t far off.

Seven times I went away to the seminary before I was done with it, or it with me. It is impossible to think back on any of it for very long without remembering the men who taught us. They were more than teachers; they were Christ figures in religious habits and mission crosses who dominated our lives. If we, in the years and decades since, have known a Diaspora, so in a sense have they. One is dead now. One went to South America and married a former nun. (“Maybe it is a dream too soon for its time,” he wrote in a letter to the Holy Father, asking to marry Phyllis and yet remain a priest; he never heard back.)

One is a recovered alcoholic who works in a ward where he was once a patient. Another has made his way back from the ledge of nervous breakdown. One is married to a black woman and has just had another child. Several are missionaries, one still teaches, and at least one other strikes me as being almost awe-filling and impenetrable as he was when I was sixteen and he was chalking on the board lines from Cicero. What follows here are selected images, some frozen in time, of men whom I think we feared and loathed and cared for in a richer way than any of us knew.

His name was Vincent Fitzpatrick and he was the seminary’s animus, whose shadow side we seldom saw, to use the terms of Jung. There was an aura, spiritual and intellectual, about him. Part of the aura, I think, came from his staying aloof. One could not imagine Father Vincent hugging someone at a sixties’ guitar mass. And because he never took the top job at the seminary, but stayed number two, he didn’t have to make the key decisions that would have brought him off the mountain. Perhaps he instinctively knew he wasn’t good at making decisions. Or maybe he liked the air up there, which is to say he was aware, I think, of his own legend. There wasn’t anything cold in this distance, just a height you couldn’t scale. I doubt if even his fellow priests felt they could scale it.

His subjects were Greek and Latin, and he ate them for breakfast, lunch and supper. He had a way of instilling terror when you didn’t have your translations prepared. As his voice grew quieter his anger mounted. A thumb raised to furrow the back of his head, as if in disbelief, was an immediate cue for passion. He was terrific at making you feel guilty, as if you’d personally injured him with your stupidity or unpreparedness. “Uh, I’m going to have to give you gentlemen the Dutch rub,” he’d say, and you could hear feathers crashing in the next room.

His face was craggy enough to be on Mount Rushmore; we used to joke he was born a thousand years before Christ. (Actually he was only in his early forties when a lot of us knew him.) His hands perpetually shook, whether he was saying mass or lecturing in a classroom. His walk was a creaky jerk, usually hurried, from side to side; we used to say he’d been run over in a chariot race. We called him the Old Roman and Zuggie, after Zugma, a Greek figure of speech. He had only an M.A. in the classics, but we felt he was smart enough to write shelves of texts. (We did find his opinion footnoted in several.) Though I recognize he was teaching, and shining, only at the level of prep school and junior college, I still believe he could have held his own on a university faculty. I looked up his master’s thesis once. It’s on a fourteenth century scholar of St. Augustine named Bartholomaeus of Urbino and is dissertation length. Other priests on the faculty had their doctorates, but Father Vincent was our symbol of academic excellence. I think all of us craved to please him. After he told me my translations had pizazz, I walked around on air. I wasn’t sure what pizazz was. It was the way he said it.

He was notorious for pop-quizzes — inkwet quickies he had run off crookedly. We’d see him coming down the hall from the faculty wing, briefcase in one hand, the loathed tests in the other, and panic would set in. “I have something here FOR you,” he’d say, coming through the door. For some reason he emphasized his prepositions. Maybe it was a private joke.

He may have had a genuine renaissance mind. I remember him saying once how he admired the ancients for being able to express their world views in literature and the arts, for that is chiefly what they had, while today’s best thinkers work out their ideas in the realm of science. He was always tinkering with some new idea himself down in the shop or in the biology lab. He kept plastic cartons in the lab filled with mysterious potions and would wander in at odd hours to inspect them. I felt sure he was on the verge of a major breakthrough, even though the plastics were there when I came and when I left. He was practically a master carpenter, he was a silk-screener, he was a photographer and developer. He directed us in Greek tragedies on the stage; he coached us in sports. There, too, he exercised his skill at withholding praise, at keeping the carrot just out of reach. In intramural softball games he liked to pitch: that was number one’s position. I remember him running bases in olive-drab canvas low-cuts and high-water army pants. He looked ridiculous.

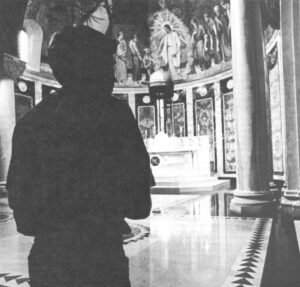

Once, I remember, he came down off the mountain. Right in front of us the animus melted to anima. Father Lawrence Brediger, one of the order’s most revered priests, a man who had spent his priestly life paralyzed from the shoulders, died suddenly in Washington. Father Vincent happened to have mass on the main alter the next morning. After the gospel he turned and faced us. It was 6:45 and all we could think of was sleep. He started to talk about Father Lawrence, got out a few sentences, cracked on a word, audibly choked back a sob. He started again, stopped. He stood staring for several minutes at his waxy, wrinkly fingers, which were clasped in front of him, then turned back to the altar and finished mass. Two hours later, in class, he was the Tiger again. That was the name a generation of classes ahead of us had given him.

On my last night in the minor seminary I was awarded the Virtus et Scientia, the school’s highest prize. They handed it out once a year to a student about to enter his novitiate. The selection was by faculty ballot and the winner’s name was kept secret up until the presentation. Father Vincent, as dean of studies, announced the award on stage in the gym. Our class was seated behind him. I felt my chances for the prize were slim, and that Dick Hennessey, who easily had the best mind of us, would get it. Father Vincent announced my name, turning 45 degrees toward me and calling me “Mr. Father Judge Mission Seminary, Nineteen Sixty-Four.” I was proud to get the award, but I was insanely proud that Father Vincent had made the presentation and chosen to call me that. Thirteen months later I was out of the seminary, my vocation gone. It might have been predicted: the Virtus et Scientia seemed to carry a jinx. Almost everyone who got it ended up leaving. Dick Hennessey persevered.

I don’t think Father Vincent ever wanted to leave Holy Trinity. He marveled at the new seminary in Virginia, I’m sure, its architectural wholeness and aesthetic beauty, but I wonder if he didn’t instinctively sense, long before we moved up there, the tyranny of big buildings and new money. The order had changed over the years, had gotten computers and millionaire donors, had seemed to move away from, as perhaps was inevitable, its primitive spirit of poverty. The paradox is that as the order became more financially secure, its vocations began to dry up, its seminarians and men in vows and even its ordained priests began jumping from the boat in alarming numbers; sometimes they jumped in rage. And Vincent Fitzpatrick, our animus, went one day to the new seminary chapel, stood there alone in a pool of amber filtered light beneath the 75-foot-high-dome and the specially commissioned stained glass and the Agean-blue mosaic pillars from Italy and said, “Oh Lord, why are you rejecting our prayers of stone?” He wasn’t a poet but that is a poet’s plea.

I saw him down at Holy Trinity this past summer. The reunion was poorly attended (they used a 1966 list of names and sent out 500 letters, scores of which came back unopened) but there were enough of us there to fill half the chapel. Father Vincent, along with Fathers Brendan and Julian, two other of my old teachers, drove down from Washington, fifteen hours straight; the next day they turned around and drove straight back — all had commitments in the East. On Saturday afternoon, in 100-degree swampy Alabama heat, we wound in awkward procession from Mary’s shrine up to the chapel, saying the rosary. At the chapel Father Vincent got up and spoke. He wore a shortsleeve clerical shirt and slightly belled black trousers with a big cuff. I kept wondering if his sister had picked out the pants the last time he was home and he’d shrugged and said okay. He is only slightly bulkier. The face is no more ancient than it ever was. He spoke the way he used to lecture in a classroom, with one hand crooked at his hip, as if he were posing for sculpture. His voice was liquid, passionate, full of tremble. But this time there seemed less willful distance, less mountain.

“I am personally overwhelmed at the significance of our being here together,” he said. He said it didn’t matter that there were only forty or so of us present, and that he “would have been glad to come if there had only been one.” He told us that lately in his own life he had been struggling with the passage of history and the meaning of change. “I think of that beautiful motherhouse of the sisters’ across the road that disappeared at the beginning of 1930, burned to the ground. And years later, the men’s novitiate, built on the same spot, burned to the ground, too. What was the meaning of that?” He said he had been listening carefully to our various stories in the previous 24 hours — where we’d been, whom we’d married, how many kids we had, our jobs. “And what I’m hearing are the values that did take root. There are spiritual values that grew up here at Holy Trinity and did not die. There was something beautiful that went out of Holy Trinity. It’s you. It’s you.” Then he said, so softly it was easy to miss, “Forgive us if we missed you. But you see, we were sorry for your departure.” I didn’t get that right away, but I think what he was trying to do was express his regret for all that had flowed on between us, for some misunderstandings and wrecked dreams.

That evening he and several of the other priests drove into town to the Ramada Inn, where most of us were staying. He sat at a row of pulled-together tables in the bar and wore an open-necked sport shirt. He fiddled with a drink. For what the bartender knew he was just some old man who had turned up on a Saturday night in a cocktail lounge for a drink with younger friends. The next day, before he drove back to Washington, I asked him if he still kept up his Latin. He fixed me with that heh-heh little smile that always had a way of cracking him open, like alabaster splintered, and at the same time parking you and your impertinence in the bleachers. “Just can’t turn off the lights some nights without dipping into a little Horace, Hendrickson”, he said.

If Father Vincent was our animus Father Brendan was our anima, although he wasn’t motherly and the softness in him was deceptive. He could be willful, like anyone else; it was just that he knew, I think, how to live between the spaces and so get along with almost anyone. Especially prep seminarians. In a way he was one of us, down to his awkward body and his absurdly baby face. For several years he was Father Terrance’s assistant in the dorms as prefect of discipline. I think what he really wanted to do was play ping pong all day in our rec room.

He was hopelessly, comically disorganized. He was a sort of religious hippie, attached to almost nothing material. Like Holly Golightly he could have kept a card on his door that said: Traveling. Except he probably would have lost the card. His room looked like Pearl Harbor after the attack. I can’t swear to this but I believe he kept his clothes, those he could find, in a plastic trash liner. I’d go visit him and he would make an effort to clear space. Usually I just sat on something — a moldy playscript, a box of yellowing correspondence (he was famous for getting out Christmas cards in July), piles of theme papers. There were stacks of partially marked papers everywhere. He always got the papers back to us but there was no telling when. At least once we got them after the term ran out and we already had our grades. It became a running gag, passing him in the hall, to ask, “Father, about those papers?” “Oh, I’ll just go and get them,” he’d say. Then he’d dissolve in something that was halfway between a sneer at you and a mock of himself. I always wondered where he slept because his bed — a cot, almost — was also buried under books and papers. Maybe he raked it on the floor every night, or maybe he climbed in with everything, or maybe he didn’t go to bed at all but stayed up reading William Faulkner or Flannery O’Connor. I had heard of Faulkner but I had no possible conception a novel could be read in terms of a symphonic structure. Father Brendan’s English classes opened windows like that. He was our audiovisual multi-media lightbox, illuminating Shakespeare, Agnes DeMille’s ballet, recordings of “John Brown’s Body.” Once, when we were at Holy Trinity, he and Father Shaun drove to Atlanta to see Bette Davis in a one-woman show. The next morning in class he imitated her reading Sandburg’s poem about fog, his slender, almost feminine fingers slipping over the lectern on “little cat feet”. Back then we considered him a raw genius. I’m not sure of that anymore but I do know something more important: he was incapable of being unkind, or seemed so, which could not be said of every priest in our midst. Even for the most leprous, disliked of seminarians he had time. Perhaps in each of us he saw a little of his own shyness.

Some of his chaos must have been worked with mirrors, for I don’t recall a curtain not rising on one of his play productions, even though back stage the cast had begun to run in ever-widening circles. The curtain would be going up and there was Father Brendan — in a tee-shirt streaked with poster paint, a cigarette with an impossible ash hanging at the tip of two fingers — applying a last dab of makeup to somebody’s face. “Get your places,” he’d shriek. For the length of the play he’d stand in the corner, mouthing every line to himself, miming nearly every gesture. By the end of the night he would have lined up on the ledge beside him several dozen spent cigarettes, like so many toy soldiers, tip to tip. It was next to impossible to get him to come out for a bow and when he did he would skulk out with acute hang-dog embarrassment. Part of his gift was that he always fouund a role for everyone, no matter what kind of horrible actor presented himself at the gym. In fact one of Father Brendan’s old tricks was not to write the script until after the number of volunteers had been tallied. His homemade entertainments, with music and specially adapted lyrics, were a maze of subplots, so that everyone could get on stage for a reasonable period. The plays had corny names (“Yes, We Have No Bonanza”) and cornier characters (Mean Marvin Mastoid, Snirk Sneath). Sometimes we’d do legitimate plays from Broadway and people from town would come. Under Father Brendan we put on “A Man for All Seasons” and “My Fair Lady”. He would go over and over our lines, blocking out movements, showing us how to swagger, to bully, to preen, to dance, to talk cockney — whatever the script called for. He looked talentless — and instead was gifted.

In the case of “My Fair Lady” he charmed the authors into letting him put on the play without royalty fees. I can see the two men in their Manhattan offices getting a letter from some priest named Brendan Smith in some place named Holy Trinity, Alabama, who wants to put on their play with an all-male seminary cast free of charge. Father Brendan could work magic with female parts — putting wigs on boys, rouge, jewels, new walks. It isn’t true he taped coffee cups under dresses to affect breasts. “No, the only allowance in that direction I remember is that when Father Vincent directed his Greek tragedies he let the heroines tie towels around their chests.”

He really didn’t need the cups: his productions had enough verisimiltude. Part of the reason he liked doing plays so much, I’m sure, was that they afforded a large number of adolescents a particular kind of maturing experience. But the rest of it, I think, was that these hokey, sometimes suprisingly adroit performances gave Brendan Smith a lampshade and cane he wouldn’t have otherwise had. In another life he might have been a lot of things, among them a clown in the circus. But fate or God or something in between had led him to a religious life. Although he had a critic’s knowledge of theater (he grew up in New York, near enough to Broadway), and although he had the crush of the pure movie-goer, he didn’t in the least seem worldly or secular. If anything he seemed out of it, more than a lot of the faculty, and we thought it our constant duty to clue him in about real life. He was out of it, in a way. He was a priest with a build of Nutty-Putty, only it was stretched over an iron of moral and spiritual principles. We knew that, I guess, but only viscerally. I’ve visited him over the last several years and I recognize how much he loved the seminary and how bad it hurt when the place died, even though he knew it had to die. In the seminary and in seminarians he had found a true apostolate. Even on his three weeks of vacation every summer he would organize trips to Radio City and Rockaway Beach with the New York-area students: he couldn’t wait till September to see them again. If there are grim absurdities in all our lives, the abiding one in his is that, like a cowboy when Westering was over, his way of life closed before he did.

Although in sense he carries on. He now lives in a large stone house in northeast Philadelphia with seven or eight young men who are students at nearby LaSalle College and who are thinking of becoming Trinitarian priests. It isn’t exactly a seminary, and it’s galaxies from the life I used to know (female friends drop by for supper; the guys go out at night with the cars), but still the place functions as a house of formation for young men seriously considering the religious life. There is common prayer in the morning, and there is an afternoon liturgy when classes are done. From the street it looks about like any other house in the neighborhood; you wouldn’t know a makeshift chapel is upstairs.

Some things don’t change much. The first time I went to see him was on a cold, cruddy day in January. Father Brendan was in the kitchen trying to get a fire lit on the stove. It was a Sunday morning and he wanted to make pancakes for the guys. (He had invited me to “brunch”.) The house was a mess, the kitchen a disaster. Things had a sort of naugahyde, dirty-shag-rug, three-legged feel. Father Brendan kept peering at the stove, then approaching it as stealthily as a burglar. All the while he asked about my family (his computer memory came up with each of their names), told me about his brother, Bud (a diocesan priest in Brooklyn), brought up a movie he’d just read about in the New York Times Arts & Leisure section. (Now, as then, he reads about film and theater much more than he ever attends; the vow of poverty has never allowed that many admissions.) He wore a baggy flannel shirt with two buttons missing. One cuff of his pants had snagged and turned itself inside out. He has put on a good deal of weight, and the face that was always fifteen years old has now caught up to, even overtaken, its more than five decades. But it still cavorts like rubber.

He got the fire lit at last but then didn’t have anything with which to grease a skillet. He tried butter — and burnt it brown. The fire was now roaring hot. His cigarette, suspended at the tip of his index and middle fingers, had grown a precarious ash; the ash began to drop into the skillet. “Quit laughing,” he sneered at me, sounding just like Mean Marvin Mastoid or Snirk Sneath. He poured out a pancake, Perversely the batter spread in all directions — it looked like an ink-blot test. Just then, as if somebody had blocked it out, one of the LaSalle students showed up. His name is Kevin and he sort of hung in the doorway wagging his head.

“Would you like me to try, Bren?” he sighed.

“Here. I didn’t become a priest to make pancakes,” my old English teacher snarled, shoving the bowl at Kevin, tromping off to save brunch and dignity.

At the reunion at Holy Trinity last summer Father Brendan preached on Sunday morning. He had to follow Father Vincent, who had stirred us the afternoon before. He spoke without fire, just in that reasoned, calming voice that used to come from the back of a gym or the front of a classroom when its owner was trying to lead us to another room where new ideas waited. Toward the end of the mass he said, “Father, it is good for us to be here. It is better for us to move on.”

©1981 Paul Hendrickson

Paul Hendrickson is studying the social and religious implications of the collapse of one U.S. Catholic seminary on his fellowship project, “Search for a Seminary: 1955-1980.”